The first time the room full of billionaires went silent for me, I was standing next to a ficus tree, holding a glass of flat ginger ale I hadn’t even wanted.

Crystal chandeliers burned overhead, throwing light across a ballroom in Scottsdale, Arizona, the kind of room you only see in magazines or on television—polished marble, walls paneled in warm oak, soft jazz from a live quartet near the stage. Men in black tuxedos and women in sequined gowns floated through the space like they belonged to it, like they’d been born knowing which fork to use and where to put their hands when everyone was looking.

And then, somehow, all of them were looking at me.

Not because of anything I’d done at that moment. I wasn’t at the podium. I wasn’t near the head table. I was seventy-two years old, sitting at a tiny round table tucked behind two potted plants near the service entrance, sharing space with drivers and security guards, my chair slightly crooked because there wasn’t quite enough room between the ficus and the wall. My shirt collar itched where the starch scratched my neck. My knuckles ached from the long drive down the interstate. I was rehearsing polite, forgettable answers in my head in case anyone accidentally spoke to me.

Then the special guest arrived.

The doors at the far end of the room opened, and the announcer’s voice rang out over the murmuring crowd.

“Ladies and gentlemen, please welcome our honored partner, Ms. Evelyn Hart of Redstone Capital, New York.”

Every head turned toward the entrance. Glasses paused halfway to lips. Even the quartet faltered for a moment before they shifted into a brighter, more formal tune. A woman in a black, precisely tailored suit stepped into the room like she’d just walked off the cover of a business magazine. Short, silver-streaked hair. Diamond studs that caught the chandelier light. The kind of presence that doesn’t ask for attention; it just collects it.

She scanned the room the way people scan a balance sheet—measured, efficient, taking everything in. I expected her gaze to lock onto the head table, where Richard Davenport, turning eighty that night, sat surrounded by his family and the executives of Davenport Industries. I expected her to cross the room in a straight line, shake his hand, and smile for the photographers stationed discreetly along the edges of the crowd.

But her eyes didn’t go to the stage.

They found me.

Her gaze landed on the little cluster of tables along the wall—on the drivers, the quiet security detail, the caterers on break—and then right on my face, as if she’d come there for me and had just now confirmed I was real. Her expression changed, just a fraction. Recognition, yes. Relief too. And something else. A kind of respect I wasn’t used to seeing directed my way in a room like that.

“Mr. Ross,” she said, her voice carrying across the ballroom even before she reached me. “I’m glad you made it.”

Every conversation near us stalled. The driver beside me straightened in his seat. A server froze, a tray of champagne flutes trembling in her hand. At the main table, Alicia Davenport’s smile hardened like cooling glass. My son, Miles, turned his head and stared at me as if I had just stood up on the table and set myself on fire.

That was the moment everything changed—the instant my life, my son’s life, and the carefully polished world of the Davenport family cracked open.

But like most turning points, it didn’t start there, under chandeliers and cameras. It started far away, in a smaller, quieter place, with the sound of ticking clocks and the smell of pine trees.

My name is Damen Ross, and I was seventy-two the year that night happened in Scottsdale, Arizona.

Until then, my life had been the opposite of a ballroom.

I lived alone on the east side of Flagstaff, Arizona, in a small house that had settled into the neighborhood long before I did. On clear mornings, the San Francisco Peaks sat blue and quiet on the horizon, watching over the town the way old relatives watch over family gatherings—present, dignified, saying nothing, seeing everything.

Ponderosa pines crowded the back fence, their tall trunks catching the wind that came down from the mountains. At night, that wind would press against the house and slip through the old siding no matter how much caulking or weather stripping I put up, creeping into the edges of the windows like a memory that never quite leaves. The pine needles scratched softly along the roof, a constant, whispering reminder that the world outside was very much alive.

Inside, the place smelled faintly of lavender, though my wife had been gone for six years.

It was in the walls. In the folded towels in the linen closet. In the sweater of mine she always liked, which I could still barely bring myself to wear. Her soap had rested in a dish by the bathroom sink for decades, and though the bar was long gone, the scent clung to the porcelain and the grout, stubborn and gentle at the same time.

Some mornings, just after sunrise, I’d pour my coffee and turn toward the kitchen doorway without thinking, expecting to see her there—bare feet on the cool tile, robe wrapped tight, hair pinned up in a way that didn’t quite manage to capture all the stray curls. For a half-second, my body would react like she was really there. Then the doorway would be empty. Only the slow burble of the coffee pot and the hum of the refrigerator would answer back.

Grief moves through time differently than other things. It doesn’t follow the clock.

Most days, to keep my mind from circling the same tired tracks, I worked.

The second bedroom had become my workshop years ago, back when my hands were steadier and my eyes could still pull focus on the smallest screws without help. Shelves lined the walls, crowded with clocks of every shape and age: brass carriage clocks, tall wooden mantle pieces, delicate porcelain cases painted with faded roses, a relic or two from Europe that somehow found their way to Arizona via estate sales and forgotten storage units.

People brought them to me from all over Northern Arizona. Some came in from the wealthier neighborhoods near the country club, carrying inherited pieces they called “heirlooms” even though they’d never wound them once. Others came from small houses and trailer parks out in the scrub, bringing in the only clock in the family, a wall piece that had hung above a kitchen table for forty years, its tick part of the family’s soundtrack. The ones from the modest homes always seemed more urgent, more loved.

I charged what I had to for parts, but the labor was mostly my own gift to the work. Clock repair is not a business you go into to get rich in the United States, not in this century. It’s a profession built on patience and a quiet satisfaction in coaxing old gears back into motion. Each system of springs and wheels is a tiny world with its own gravity. When I focused on that—on the alignment of teeth, on the right amount of tension in a mainspring, on the gentle oiling of a pivot—I could almost believe the universe had some order left in it.

That rhythm had once been shared.

When my son, Miles, was a boy, he used to drag a milk crate into the workshop and sit beside my bench while I worked. His fingers would end up smudged with oil as he carefully held tiny parts in his small hands, eyes wide as I explained how one gear influenced another, how the tick and the tock were nothing more than a conversation between balance and restraint.

“Time is just controlled falling,” I remember telling him once, demonstrating how a pendulum swings. “Gravity pulling, the mechanism catching, over and over again. The art is in how slowly you let things fall.”

He listened then. Asked questions. Believed I knew something worth knowing.

That boy disappeared the day he married into the Davenport family.

Their world was nothing like mine. Their world was marble floors that stayed cool even in the Arizona heat and long, glass-walled rooms overlooking curated gardens with imported olive trees. Their parties were wine tastings and charity galas in Phoenix and Scottsdale, the kind that got mentioned in society pages and local business journals. Their conversations floated around stock options, real estate in other states, school rankings, and vacation homes on distant coasts.

They shook hands with a certain stiffness that said they had already totaled you up in their head the moment you walked into the room—net worth, status, usefulness—before you’d even opened your mouth.

I learned quickly that a clock repairman from Flagstaff did not fit the picture they wanted.

Especially not when Alicia Davenport became my daughter-in-law.

I met Alicia in the polished foyer of the Davenport home for the first time, after Miles brought me down for a dinner he framed as “important.” She stood at the base of a staircase that swept up one wall like something out of a movie, dressed in a fitted dress in a shade of deep blue that made her look like she belonged under those chandeliers. Her smile was perfect, practiced, just shy of warm.

“Mr. Ross,” she said, extending a hand with nails that looked like they had their own budget. “Miles has told me so much about you.”

I believed her at the time. I wanted to.

The truth, which would come out much later in a very different room, was that she understood my world far better than I understood hers. But back then, all I could see was a girl from the Davenport house, with Davenport expectations, and a Davenport way of bookmarking your worth with one brief, measuring glance.

The first Thanksgiving after their wedding told me everything I needed to know.

The Davenports hosted it, of course, at the big house on the edge of Phoenix, where the city began to thin out toward the desert. Cars lined the long driveway, each more polished than the last, metal gleaming under the mild Arizona sun. Inside, the air smelled like roasted turkey, butter, and expensive candles.

I arrived in my best jacket, the same one my wife had insisted still made me look “handsome” the last Christmas we’d had together. A young man I didn’t recognize took it without really looking at me. I followed the sounds of conversation toward the dining room, expecting to see a long table in the center, maybe an extra folding table pressed against the wall for the overflow.

There was a long table, set under a chandelier with a polished silver runner and china so fine I could see my reflection in the plates. At that table sat the Davenports and their closest orbit—Richard at the head, his wife beside him, Alicia and Miles positioned where everyone would see them, key business partners and spouses arranged around as if by choreography.

I stood in the doorway for a moment, feeling like a man who had wandered onto the wrong movie set.

“Dad!” Miles said, coming toward me. “You made it.”

Before I could ask where to sit, a woman in a black dress with an earpiece—clearly part of the catering staff—touched Miles’s elbow.

“Mr. Davenport, we’ve set up the additional seating where you requested.”

He nodded, then turned to me with an apologetic wince, the kind of expression people use when their dog has chewed your shoe.

“There were some… last-minute changes,” he said. “But we’ve made accommodations.”

He led me away from the main dining room, down a narrower hall, past a swinging service door. I heard laughter behind us as someone at the big table delivered a punchline. The kitchen staff moved around us like we were part of the scenery.

At the far end of the kitchen, near a side exit, a small card table had been set up with a linen cloth draped over it. Two folding chairs sat on either side. On the table: a single candle, a basket of rolls, a place setting. Beside it sat two caterers already halfway through small talk about somebody’s college plans.

“This is you,” Miles said, too quickly. “We just—we had to keep numbers at the main table balanced for some investors. You understand.”

I did understand. Not that he had meant to hurt me, but that it had never even occurred to him that I might feel the way I did in that moment. I sat where they asked me to sit, in the corner with the catering staff, listening to the laughter from the other room as if it were coming from another country.

During dessert, Alicia caught my eye over the heads of the guests, smiled, and lifted her glass in my direction.

It was the kind of smile you give someone you’ve put “upstairs” at a family wedding, in a room for children and concessions.

The years that followed were full of small cuts like that. Individually, they might not have looked like much from the outside. Taken together, they could have bled a man dry.

At Christmas, they asked gently if I could “keep the conversation light” and avoid talking about my shop or my work because it sounded “too blue-collar” for some of the guests. At one of Miles’s promotion dinners, held in a private room in a luxury hotel in downtown Phoenix, they seated me behind a structural pillar where I could hear but barely see the speeches, my view of my son half-obscured while the “people the company needed to impress” sat at the main table, fully visible.

I never confronted anyone. I told myself conflict would only put Miles in a difficult position. I took my plate and sat where I was told, telling myself it was temporary, even though some quiet, honest part of me knew it wouldn’t change.

The one bright spot through all of this was my grandson.

Liam arrived with his father’s eyes and some of his grandfather’s stubbornness. From the time he could toddle, he’d come barreling toward me at gatherings, arms wide, tie crooked, hair already escaping the careful part Alicia had combed into it. He’d throw himself into my arms with the full, unquestioning trust only a child can give.

Each time, Alicia or a nanny would appear a moment later, apologetic but firm, gently tugging at his sleeve.

“Careful, Liam. Don’t wrinkle your clothes,” she’d say. Or, “We’re about to take photos. Come away for just a minute.”

Over the years, the phrases changed, but the message stayed the same: There was a right way and a wrong way to belong to that family, and hugging the old man in the wrinkled shirt for too long did not fit the picture.

I accepted all of it. Or at least, I thought I was accepting it. In truth, I was collecting it, storing it, like dust in the tiny gears of a clock. At some point, it was bound to clog something important.

The email that finally shifted the gears came on an ordinary weekday morning.

I was at my kitchen table in Flagstaff, finishing a second cup of coffee and flipping absentmindedly through a local newspaper. The light was still soft, slipping in through the pine branches outside the window. The wall clock above the kitchen door ticked steadily.

At 7:32 a.m., my phone buzzed on the table.

The screen lit up with a name: Alicia Davenport.

A small, familiar knot tightened in my stomach. Alicia didn’t email me often. When she did, it was usually to convey some information about an event in a tone that hovered somewhere between professional and polite distance, like she was contacting a subcontractor.

I opened the email.

“Mr. Ross,” it began. Not Damen. Never Dad.

She wrote that Richard Davenport’s eightieth birthday gala would be held in Scottsdale at six o’clock in the evening on the fifteenth of the month. The event would be “formal attire,” and it was “essential” that I arrive on time and dress in a manner “appropriate to the Davenport family and their partners.” She mentioned that key investors and business leaders from across the United States would be present.

There were no exclamation points. No little personal note about looking forward to seeing me. Just time, place, dress code, expectation.

I read the email twice, the words growing heavier on the second pass. In the quiet of my kitchen, the house seemed to settle around me with a long, slow exhale.

For a moment, I simply stood there, phone in my hand, feeling something sink in my chest that wasn’t quite anger and wasn’t exactly sadness. It was a kind of tiredness, old and deep, that had nothing to do with my age.

An hour later, my phone rang again. This time, it was Miles.

“Hey, Dad,” he said, his voice carrying that strained politeness I’d come to recognize, the one he used when he needed something to go smoothly. “Did you get Alicia’s email?”

“I did,” I said.

He cleared his throat. “So, this gala—it’s a big deal. There are going to be some really important partners there. From New York, from Los Angeles. People I’ve been trying to build relationships with for years. I just…” He paused, searching for words that wouldn’t sound the way they sounded. “I was wondering if you could… you know… wear something really formal. And maybe keep conversation more current. You know, nothing about… the shop or… that earlier work you used to do. People might not… get it. It’s a different crowd.”

He didn’t have to spell it out. The picture was clear enough.

“You’re worried I’ll embarrass you,” I said, softly, to make it easier for him.

“That’s not what I’m—” He stopped. I could hear him shift the phone from one ear to the other, like the discomfort might slide to the other side of his head. “It’s just… complicated. I want everything to go well. For all of us.”

For all of us. It was always phrased that way, as if my shrinking made the table larger for everyone else.

“I understand,” I told him. Because arguing in that moment would only have made him more uncomfortable, and I had spent years absorbing that discomfort so he didn’t have to feel it.

We talked logistics for a few more minutes—time, directions, whether I would drive or stay overnight. Then the call ended. I stood in my narrow hallway, phone still in my hand, listening to the silent house.

Eventually, my eyes drifted to the old cardboard box on the shelf in the hallway closet.

It sat under a folded blanket, pushed back against the wall where it wouldn’t be in the way. The box had followed me through three moves, two jobs, and one devastating loss. Its corners were softened with age, tape yellowed. For years, I’d told myself I was going to sort through it, decide what was worth keeping, and throw out the rest.

I never did.

I pulled it down and set it on the hallway floor.

Inside were documents I had not looked at in decades. Technical diagrams. Hand-drawn schematics. Old contracts with names of companies that no longer existed or had long since merged into larger conglomerates. Among them were pages related to small technical work I’d done in my thirties and forties, when my wife first got sick and the medical bills had begun to rise like a second mortgage on our life. Back then, I’d taken work wherever I could get it—consulting on components, refining designs, building prototypes in my tiny garage workshop for companies that barely remembered my name by the time the ink was dry on the next quarter’s report.

One company, though, I remembered very well.

Davenport Industries. Before they were Davenport Industries, before they had a glass tower in downtown Phoenix, they were something smaller—still wealthy, still powerful, but not yet the national name they’d become. I’d done a short series of projects for them back then, back when my wife was spending more time in the hospital than at home and every dollar felt like a bucket in a sinking boat.

Richard Davenport had praised my work at the time. Told me I had a “gift for mechanical insight.” Shook my hand in a small office in an older building, not the gleaming headquarters he’d later build. Then the projects ended. My wife’s health took a steep turn. The details of that time blurred into nights in hospital chairs and days in the shop trying to keep the lights on.

I didn’t know why I’d kept the papers from that period. Maybe because I hadn’t had the heart to throw away the last physical reminders of a version of myself that still believed big companies noticed the men who did work for them.

I lifted a few of the stacks, saw my own handwriting on the edges of diagrams. My diagrams had always been distinctive: a particular way of annotating stress points, a habit of circling areas of concern with a double loop instead of a single one. I recognized it instantly and felt that old mix of pride and sorrow. I closed the box gently and slid it back into the closet.

I wasn’t ready to revisit that past. Not yet.

That evening, I packed a small overnight bag and laid out the best shirt I owned—the one my wife had always taken extra care pressing when she knew we were going somewhere “fancy,” even if I never quite felt I fit the description. I checked the weather for Phoenix on my phone. Mild for February, a light chance of rain along the interstate. I filled the truck with gas at the corner station where they still recognized my face, then returned home to set my alarm.

The drive from Flagstaff to the Phoenix metro area is one of those stretches that reminds you just how large and varied the United States really is. You start in the cool pines and thinner air of Northern Arizona, then drop down through canyons and along desert slopes until the world changes around you—trees thinning, rocks growing redder, the air warming even in winter. The road feels like a long exhale.

On the afternoon of the gala, I locked my front door behind me as the last of the sun slanted through the pines in my backyard. The house stood quiet, filled with the soft tick of clocks and the ghost of lavender.

As I turned the key, I felt a strange mixture of quiet sadness and a thin, persistent thread of hope.

Maybe, I thought as I walked to the old pickup truck, I would get a real moment with Liam that night. No rushing. No nanny hovering. Maybe ten minutes together where I could talk to him like his grandfather instead of a bit player in the background of his parents’ carefully curated life.

It wasn’t much to hang a long drive on, but it was something.

I started the engine. The truck coughed once, then settled into the rough-but-familiar idle I knew so well. Gravel crunched under the tires as I pulled away from the house. Pine trees gave way to highway, and soon enough I was heading south on Interstate 17, the asphalt ribbon carrying me down through the American Southwest.

The farther I drove, the more Flagstaff receded in the rearview mirror, shrinking from a town into a cluster of distant lights, then into nothing at all. Mountains faded behind me, blue shoulders dissolving into the hazy horizon. The sky above the desert stretched wide and pale, an enormous bowl of soft light pressing down on low scrub and rock.

There is a particular kind of loneliness on those stretches of interstate, the kind that doesn’t feel like a lack of people but like an excess of space. Miles and miles of open land, broken only by the occasional rest area, gas station, or faded billboard promising a diner that might not even exist anymore.

The road hummed under the tires. The radio was off. I had only the wind against the cab and the sound of my own thoughts for company.

I found myself drifting back to memories I had not asked for: Miles as a boy in the passenger seat on this same highway, pointing out hawks standing sentinel on fence posts, asking me how far the desert went, or why the sky changed color as we drove.

He had looked up to me then. Asked how things worked. Believed that the answers I offered mattered.

Somewhere along the way, as he moved out of our small house and into the orbit of the Davenports, those questions had dried up. The man he had become rarely asked me anything at all anymore, except whether I could arrive at six, whether I could wear something formal, whether I could limit my stories to “light topics.”

I told myself not to dwell on it. But thoughts, like vultures, have a way of circling over the weakest parts of you when you are alone in the desert with hours to go and nothing but the road ahead.

Halfway between Flagstaff and Phoenix, the weather began to change.

At first it was just a faint haze in the distance, a slight blurring of the horizon. Then the light shifted. A thin veil of dust lifted from the desert floor and hung in the air, soft and beige. The road ahead grew less distinct. I felt the old tires shift slightly on the grit that began to gather on the pavement.

The desert is beautiful from a distance—photogenic, the way travel magazines like to frame it. Up close, in a wind that carries sand into your eyes and onto the road, it has edges sharp enough to remind you why so many stories from these regions are about survival.

I tightened my grip on the steering wheel.

Rain joined the dust in thin, slanting lines, streaking the windshield and turning the outside world into a watercolor of browns and grays. The wipers sighed back and forth. My headlights cut two cones of dim light into the haze.

I should have been thinking about the gala. About what I’d say if someone important asked me what I did. About how I might keep from doing whatever it was Miles was so afraid I’d do. Instead, I kept thinking about a question I didn’t know how to answer:

Why was I still trying so hard to belong in a world that had never made room for me?

A few miles past a rest area—one of those places with a few picnic tables, a bathroom, and a vending machine that may or may not work—I saw it.

A bright, insistent flash on the shoulder ahead. Hazard lights.

A car sat angled toward the desert, its nose pointing slightly off the asphalt, like it had been forced over suddenly. Through the film of rain and dust, I could just make out the sleek, low shape of a luxury electric car, the kind I’d only ever seen on television or passing me at high speed as if I were standing still.

As I drew closer, I saw a figure standing beside it.

A woman. Mid-fifties, I guessed, even from a distance. Dressed in a tailored suit that did not belong on the shoulder of an Arizona interstate. Her arms were crossed tightly over her chest, not in impatience, but in the kind of controlled worry that comes when you’re used to solving problems with a phone call and a credit card, and suddenly both feel a little less useful.

I checked the clock on the dashboard. If I kept driving, I might just barely arrive at the Davenport estate on time, maybe even early enough to avoid any pointed looks about punctuality. If I stopped, I might be late. Alicia would notice. She would comment. There would be a subtle tightening in Miles’s jaw when she did.

I slowed down.

I didn’t think about it. I just did. My hands moved before the rest of me could talk myself out of it.

I pulled over ahead of the stalled car and eased onto the shoulder, gravel popping under my tires. The wind hit me as soon as I opened the door, carrying dust and a faint, metallic tang from some distant storm.

“Ma’am?” I called out, raising my voice to be heard over the wind and passing traffic. “You alright?”

She turned toward me.

Up close, I could see the lines at the corners of her eyes and mouth, carved there by years of thinking hard and smiling in calculated doses. Her makeup had held up well under the weather, but her suit jacket was damp at the shoulders, a few strands of hair blown loose from their careful style. She looked me over in a quick, efficient sweep—taking in the old truck, my worn but clean shirt, the toolbox I pulled from behind the seat—then nodded.

“My car just… died,” she said, voice clipped but steady. “The screen went black, and I lost power before I could get to the exit. It won’t restart. My phone has a signal but roadside assistance is ‘experiencing longer than usual wait times.’” Her mouth twisted slightly on the phrase, mimicking the automated voice.

I popped the hood latch.

“I’m not an electric vehicle expert,” I said, “but I know how things flow. Might be something simple.”

“Can it be simple?” she asked, half to herself. “Nobody ever told me anything could be simple with these.”

I smiled faintly and lifted the hood. Heat rose up, carrying the faint smell of hot electronics and dust.

Years of repairing clocks does not teach you the specifics of electric car systems. But mechanics, at their heart, all speak a similar language. You learn to read where energy is supposed to go and what happens when it stops getting there. You learn to listen.

I checked connections. Cooling lines. The placement of sensors. Dust had collected in a critical spot, clogging a small but essential part of the cooling system. The desert gets into everything if you let it. A simple problem, really, but one that no amount of software could fix without someone willing to stick their hands into the physical world.

“Got a brush?” I murmured, more to myself than to her, then remembered who I was talking to. She shook her head, starting to reach for her phone as if to order one from somewhere.

“I’ve got it,” I said, stepping back to my truck. The toolbox came with me on almost every drive. Old habit. It held the tools I trusted—collected over years, handles worn smooth where my fingers had pressed them countless times.

I found an old brush with stiff bristles, the kind I used to clean gears in larger movements, and went back under the hood. Carefully, I cleared the dust from the sensor, watching as the components beneath began to breathe again. I tightened a connection that had shaken loose, a small adjustment, but essential.

All the while, she watched me. Not hovering, not micromanaging. Just observing the way someone used to reading graphs watches a craftsman’s hands.

When I was finished, I stepped back.

“Try it now,” I said.

She slid into the driver’s seat. The rain had softened to a mist, pattering lightly against the windows. A second later, the headlights flickered. The dashboard lit up again, colors blooming in the dark interior. The engine system hummed to life, that distinct electric whir replacing the dead silence from moments before.

She let out a breath I realized she had been holding.

“I don’t know how you did that,” she said, stepping back out and closing the door, “but I’m very glad you did.”

“Dust,” I said. “Happens. This road isn’t kind to delicate things.”

Her eyes flicked to my truck, then back to me.

“And you carry tools,” she said. “Of course you do.”

“If I didn’t, I’d be stranded a lot more often,” I replied.

She studied me for another heartbeat, then held out a hand.

“I’m Evelyn Hart,” she said. “From Redstone Capital. New York.”

She said it as if the name should mean something, and in certain circles, I suppose it carried weight. I was not in those circles. Not yet.

“Damen Ross,” I said, taking her hand. It was cool, firm. No ornamental rings, just a watch with a simple but expensive face. “From Flagstaff.”

Her gaze softened a fraction.

“Flagstaff,” she repeated, tasting the word like she hadn’t said it in a long time. “Where are you headed, Mr. Ross?”

“Phoenix area,” I said. “Scottsdale, actually. Some family event for my son’s in-laws.”

Something passed behind her eyes. Recognition? Maybe not of me, but of the world I was headed toward.

“Davenport?” she asked.

I blinked, surprised. “Yes.”

She made a small sound, halfway between a laugh and a sigh.

“Well. What a coincidence.” She glanced at the time on her watch. “I’m due at the Davenport estate myself. I… owe you a ride, at the very least. Please, let me put your truck in touch with a towing service and drive you the rest of the way. It’s the least I can do.”

The image flashed unbidden into my mind: me, a seventy-two-year-old clock repairman in a suit that had seen better years, pulling up to the Davenport estate in a sleek luxury electric car beside a high-profile investor from New York.

I didn’t need to imagine Alicia’s reaction. I could feel it.

“Thank you,” I said, “but if I show up beside you, I’ll cause more trouble than it’s worth. The truck’s fine now that the weather’s eased. And I know the way.”

She studied me for a long moment, brows drawing together, understanding much more than I had said.

“You know,” she said slowly, “most people drove past without stopping. You’re the only one who pulled over. Why?”

I shrugged, feeling the wind pick up again. Out on the highway, another line of cars passed, their taillights smearing red in the mist.

“I know what it feels like to stand on the side of the road hoping someone will see you,” I said. “Figured I’d rather be the person who stopped.”

Something in her expression shifted at that. The sharp, businesslike edges softened, revealing a hint of weariness, maybe even loneliness, that matched something in me more than our surroundings would have suggested.

“Then I’m doubly glad you did,” she said. “Drive safe, Mr. Ross. I’ll see you… later.”

She hesitated on the word, as if choosing it carefully. Then she climbed back into her car, turned on her blinker, and eased onto the highway. I watched her taillights disappear down the interstate, red glowing faintly through the rain, until they were just two dots swallowed by distance.

I got back into my truck.

Something in me felt… lighter. Not because anything in my life had changed, but because I had done a simple, decent thing and been seen for it, even briefly.

I had no idea that the woman whose car I’d just fixed would, a few hours later, stand beside me in a Scottsdale ballroom and tilt the world of the Davenport family on its axis.

The rain eased as I approached the outskirts of the Phoenix metro area. The sky shifted from the mottled grays of passing weather to the softer blues of early evening. The desert gave way to suburbs, then to wide, well-lit roads lined with palm trees and low, luxurious properties. Traffic thickened. Streetlights flicked on in measured succession.

By the time I turned onto the long drive leading to the Davenport estate, the sun had slipped behind the mountains west of the city, leaving behind a smear of orange and purple light that reflected off the polished windows of the house.

The Davenport estate looked more like a resort than a private home. The main building sprawled across the property, low and sleek, every line deliberate, every angle meant to impress. Floor-to-ceiling glass revealed glimpses of high ceilings and art pieces that probably had their own insurance policies. People moved inside like figures on a stage.

I rolled up toward the main entrance, where a row of luxury vehicles—sedans with glossy black paint, sports cars that looked like they belonged on a racetrack, one or two SUVs so high-end they might as well have been private jets with wheels—waited in a slow, orderly line for the valet.

As I eased the old truck forward, a young valet in a crisp black uniform stepped away from the glossy sedan he’d just parked and held up a hand.

“Sir,” he said, polite but firm, leaning down to my window. “We’re directing service vehicles around the side tonight. If you could pull down that lane, someone will assist you there.”

He gestured toward a narrower driveway running alongside the house, past the garages and toward the service entrance.

Service vehicles.

I looked behind me at the line of cars. Their drivers, tucked comfortably in leather seats, did not meet my eyes. They didn’t have to. The separation was right there in the asphalt.

“Of course,” I said, forcing my voice to stay even. “Wouldn’t want to block anyone important.”

If he caught the edge in my tone, he didn’t show it. He gave a quick nod and stepped back. I turned the wheel and guided the truck toward the side lane.

There’s a different atmosphere near the service entrance of a place like that. The front of the house smells like perfume, cologne, and expensive flowers. The side smells like whatever’s cooking for the guests, exhaust from the delivery trucks, and a faint trace of cleaning chemicals. People move faster there, less like they’re on display and more like they’re racing an invisible clock.

I parked where an attendant pointed and walked toward the side door. A security guard gave me a once-over, compared my name to a list, and then waved me in.

Inside the service hallway, the air felt colder. The lighting was more utilitarian than flattering. Staff walked past with trays of food, stacks of glasses, extra linens. I could hear the muffled hum of the main party beyond, the deeper note of a string quartet, the higher buzz of laughter and conversation.

Alicia stood waiting at the junction between the service corridor and the main hall, as perfectly arranged as the rest of the evening.

Her gown was silver, shimmering under the recessed lights, catching every movement in a way that made her sparkle even when she stood still. Her hair was swept up, earrings catching the light as she turned her head. She looked like she belonged on the cover of some regional “Most Influential” list.

Her expression, however, did not sparkle.

“Mr. Ross,” she said. “You’re late.”

I checked the time. I wasn’t. I was exactly on the dot. But in the Davenport world, “on time” was a flexible concept that often meant “you arrived with just enough minutes for us to keep reminding you who sets the clock.”

“There was some weather on the interstate,” I said. “And… a small delay. But I’m here.”

Her eyes flicked down my clothing. I had done my best—pressed shirt, old but clean blazer, polished shoes that still held a dull shine.

“That shirt is… more wrinkled than I’d hoped,” she said, voice low, as if she were doing me a kindness by whispering her criticism instead of announcing it. “But we’ve already made accommodations.”

Accommodations. That word again.

Without asking if I wanted a drink, without asking how the drive had been, she turned and guided me down a hallway that ran parallel to the main ballroom. Through small, high windows, I could glimpse the party: crystal chandeliers, white tablecloths, a stage at one end with a podium and a banner bearing Richard Davenport’s name and the number eighty in tastefully understated lettering.

She did not lead me toward the front.

Instead, she brought me to a small cluster of tables squeezed against one wall, half-hidden behind tall potted plants that served as a decorative border between “the event” and “everything else.” At those tables sat drivers in black suits, security staff with earpieces coiled discreetly along their necks, and a few personal assistants who probably knew more about the lives of their employers than the employers themselves did.

“This is where we’ve seated vendors, staff guests, and… extended family,” Alicia said. “You’ll have a clear view of the stage from here. And you’ll be able to enjoy the party without… pressure.”

Pressure.

I looked at the tall plants, their glossy leaves forming a natural screen between this corner and the main floor. I could see everyone out there. They just wouldn’t see me unless they were trying.

“Thank you,” I said. The words came out hollow.

She nodded, apparently satisfied.

“Richard is making his entrance soon, and our primary investor is arriving later this evening,” she said. “Please remember what we discussed about conversation. The tone tonight is celebratory and… forward-looking.”

“Don’t worry,” I said quietly. “I won’t shame the family by talking about how I work for a living.”

Something flickered in her eyes—guilt, annoyance, an old reflex—but it vanished quickly. Her smile snapped back into place.

“It’s good you’re here,” she said. “Really.”

Then she stepped through the curtain of leaves back into the ballroom, disappearing into the light and the sound.

I sat down at the tiny table. The driver beside me gave me a sympathetic nod, the kind two soldiers might give each other when they find themselves in the same trench.

From my corner, I watched.

Guests floated through the ballroom like they’d rehearsed it: greeting Richard at the head of the room, laughing at his jokes, patting his shoulder with the kind of warmth that has a half-life measured in business deals. The string quartet at the far end of the room played an elegant medley of songs. Waiters moved through the crowd with trays of champagne and tiny bites of food that probably had French names.

Miles stood near the main table, talking with a group of older men in dark suits and women in jewel-toned gowns. Even from across the room, I could see the way he held himself—shoulders back, smile sharp but polite, hand gestures controlled. He’d grown into his role at Davenport Industries, become someone the business press in Arizona liked to profile as “the next generation of leadership.”

He looked comfortable in that skin. Too comfortable, sometimes.

He saw me. Our eyes met across the distance and the foliage. For a split second, something unguarded crossed his face—something like shame, or fear, or a quick calculation of how visible I was to the people around him.

Then he turned away, laughing at something one of the investors said, placing a hand on the man’s arm as if nothing else existed outside that conversation.

That small movement cut deeper than Alicia’s critiques of my shirt.

The party grew louder. The sound swelled and receded like the tide. I sipped at the ginger ale a waiter had set in front of me—it was easier to keep saying no to alcohol altogether than to try and keep track in a room like that—and tried not to let my heart drift toward resentment.

I might have kept stewing there all night if not for a streak of motion that broke through the crowd like a comet.

“Grandpa!”

Liam burst free from the orbit of his nanny and bolted toward my corner, his small dress shoes barely touching the carpet. He was eight now, taller, his soft features sharpening with age, but his smile when he saw me was exactly the same as when he’d been three and sticky with ice cream on my front porch in Flagstaff.

He reached me, arms already out, and I rose from my chair, feeling a rush of pure, undiluted joy sweep away everything else.

Before his arms could close around my waist, the nanny’s hand landed gently but firmly on his shoulder.

“Liam,” she whispered, glancing nervously toward the room. “Remember what Mommy said. Grandpa’s working tonight.”

Working.

The word landed in my chest like a dropped weight.

I froze, my arms still half-open. Liam turned his head to look up at her, confusion wrinkling his brow.

“Working?” he repeated. “But he’s Grandpa.”

The nanny offered a small, apologetic smile in my direction.

“Come on,” she murmured. “They’re about to cut the cake.”

She steered him away. His eyes met mine over his shoulder, full of questions he didn’t yet have the vocabulary to ask.

I sat back down.

I lowered my gaze to the table so he wouldn’t see the hurt on my face.

The room spun on without missing a beat. The quartet shifted to a more triumphant piece as servers began circulating with champagne for a toast. Someone tapped a microphone to test it, sending a sharp pop through the speakers.

People kept glancing toward the main entrance. The “feature investor,” I realized, had not yet arrived. In the business world, that kind of delayed entrance was a performance in itself—a reminder that some people are important enough to be late.

When the announcer finally stepped up to the microphone and spoke again, the whole room seemed to lean in.

“Ladies and gentlemen,” he said, “as we celebrate Richard Davenport’s eightieth birthday and the continued success of Davenport Industries across the United States and beyond, we are honored to welcome a very special guest this evening. Please join me in welcoming our newest strategic partner, Ms. Evelyn Hart, managing director of Redstone Capital, New York.”

The quartet stopped. Applause rose in a wave as the doors at the far end of the room opened wide.

And there she was.

Evelyn stepped into the ballroom with the confidence of someone who knew that rooms like this often shifted their furniture, their focus, even their future, around her arrival. She had changed since the highway—her suit was trade-show perfect now, black with a subtle sheen, a silk blouse catching the chandelier light. A small, tasteful pin bearing her firm’s logo gleamed near her collarbone.

She moved through the parted crowd without hurrying, without scanning the room anxiously. She walked like a woman who had already read the terms and conditions and come prepared to negotiate.

I expected her to go straight to Richard Davenport, seated at the head table, flanked by his family and executives. He had half-risen from his chair already, his practiced smile fixed in place, hand extended in anticipation.

Instead, she paused. Her eyes swept across the room once, twice, as if checking a list.

Then, very clearly, very deliberately, they stopped on me.

The applause faded, confused. Conversations that had just started up again stumbled. Even the clink of glass on glass seemed to hesitate.

Evelyn changed course.

She walked past the head table, past the cluster of executives, past the beaming PR manager who had likely been planning where to position her for the best photos. Her heels made a clean, precise sound on the marble floor that seemed, in that silence, louder than the music had been.

She came to a stop right in front of my little table behind the plants.

“Mr. Ross,” she said, her voice carrying easily across the quiet room, amplified not by speakers but by the stunned attention now focused on us. “I’m glad you made it.”

You could feel the confusion ripple through the crowd like the aftershock of an earthquake. Heads turned. Eyebrows rose. A few people checked their programs, just in case they’d missed a name.

At the head table, Alicia’s posture stiffened, shoulders drawing back as if bracing for impact. Richard’s smile faltered, then froze altogether. Miles stared at me as if he’d just discovered I’d been living a secret life this whole time.

Evelyn turned to face the room, but she kept one hand resting lightly on the back of my chair, anchoring me to the moment.

“Before we begin the formal program,” she said, “I’d like to say something.”

It was not in the script. I knew that from the way the event coordinator near the stage suddenly looked down at her clipboard, eyes scanning frantically for notes that weren’t there.

“When I agreed to come to Scottsdale,” Evelyn continued, her voice calm, “and when Redstone began the due diligence process for this partnership, my legal and technical teams requested a full archive of Davenport Industries’ historical project documentation.”

There was nothing controversial about this so far. That’s what firms like hers did—looked into the bones of a company before tying their fortunes together.

“What we didn’t expect to find,” she said, “was a story buried in those documents. A story about the origins of one of Davenport’s most profitable divisions. And a story about a man sitting in this room tonight.”

A murmur rolled across the ballroom. People shifted in their seats. A few leaned forward.

Evelyn’s hand tightened slightly on my chair.

“Our analysts found early design sketches and technical notes for a component that eventually became central to Davenport’s advanced timing and control systems—a division that now brings in a significant portion of the company’s revenue nationwide,” she said. “Those sketches were detailed. Precise. Signed. They bore a distinctive style of annotation.”

She paused, then glanced down at me with a small, knowing nod.

“And they were written,” she finished, “in the hand of Mr. Damen Ross, of Flagstaff, Arizona.”

The silence that followed was not empty. It was dense, packed with disbelief, recalculation, and a hundred private thoughts slamming into one another at once.

Richard Davenport’s face, already pale with age, drained of what color was left. His fingers, wrapped around the stem of his champagne glass, tightened. Alicia stepped back from the head table, as if the floor near it had become unstable. Miles’s mouth opened slightly, but no sound came out.

I gripped the edge of the table, heart pounding so loudly I could barely hear the room.

Evelyn kept going.

“In reviewing these materials,” she said, “my team noticed something else. The dates on Mr. Ross’s designs corresponded with a period when his wife was undergoing serious medical treatment. During that time, he took on small technical contracts from companies across the state—including, at the time, a younger Davenport Industries.”

She let that sink in. It didn’t take long.

“As someone whose firm works across the United States, I’ve seen all kinds of stories in corporate histories,” she said. “Some inspiring. Some… instructive. But rarely do we find such a clear instance of foundational work being rendered invisible—not by accident, but by design.”

All eyes shifted, almost as one, toward Richard.

Richard Davenport, patriarch of the family, founder of the company that bore his name, slowly set his glass down.

“I don’t…” he began. Then he stopped, swallowed, and started again. “This is not the time—”

“Actually,” Evelyn said gently but firmly, “I think it is.”

Her tone left no room for argument. It wasn’t loud or aggressive. It was simply certain.

She stepped slightly aside, giving him space but not distance.

“Mr. Davenport,” she said, “when we shared these findings with you last week, you acknowledged Mr. Ross’s contributions. You acknowledged that the early mechanism your company built a division on was derived directly from his designs. You also said something else. I believe it would be best for your family, your partners, and your employees to hear that from you, in your own words.”

There are moments in a man’s life when he stands at a crossroads between the story he’s told for years and the truth he’s spent just as long avoiding. You can see it happen in the way their shoulders shift, in the way their neck muscles tighten, in the way their eyes dart across the room looking for exits that are no longer there.

Richard Davenport closed his eyes for a long second. When he opened them again, some of the corporate polish had slipped. He looked suddenly very old. Very human.

“I remember,” he said, his voice rough, “the work Mr. Ross did during that time.”

All focus in the room sharpened. You could have heard the clink of a single fork against a plate.

“I remember,” he continued slowly, “that he delivered designs that solved a problem my engineers were struggling with. I remember praising his insight. I remember… taking those designs into our development pipeline. I also remember that his wife was very sick. And that he… needed money badly.”

His hands shook.

“I did not pay him fairly for what he gave us,” Richard said. “I knew he was desperate. I knew he did not have lawyers. I knew he would not question the contracts we pushed across his table. And I knew that what he had given us was worth much more than we were admitting, even then.”

He swallowed again, the sound audible in the quiet room.

“I told myself it was business,” he said. “That he was lucky to get anything at all. I told myself we would revisit it later, when the company was more stable. But later never came. Not for him. Only for us.”

His words came out slow and heavy, like stones dropped into deep water.

“I took advantage of a grieving man,” he said. “A man who was trying to save his wife. I’ve carried that choice like a weight for decades. I built a piece of my legacy on his work, and I never gave him the recognition or compensation he deserved. And I am deeply, deeply ashamed.”

No one moved.

You could feel the temperature in the room shift—not physically, but in the way people looked at each other, at their glasses, at me. Investors from other states who barely knew the Davenports personally sat upright, their instincts telling them they had just stumbled into something that would never make it into the polished company brochure.

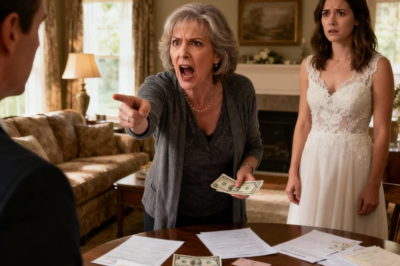

Alicia stepped forward, her eyes shining—not with tears she’d rehearsed for the cameras, but with something rawer.

“I need to say something,” she blurted, surprising even herself. “About… me. About… all of this.”

She looked at Richard, then at Miles, then at me.

“I didn’t grow up in this world,” she said, gesturing vaguely at the room—the chandeliers, the gowns, the tables. “I wasn’t born into marble floors and private schools. I grew up in a trailer park in southern New Mexico. Our ‘kitchen island’ was a folding card table. Our ‘backyard’ was gravel and scrub. I spent my whole life terrified of being dragged back into that world.”

Her voice wavered, then steadied.

“When I met Miles, his life looked like everything I had ever dreamed of and everything I had ever been afraid of,” she said. “I learned fast how to dress, how to talk, how to shake hands the right way. I polished every rough edge I had until I barely recognized myself. And somewhere along the way, I started to believe that if anyone saw where I came from—if anyone saw someone like you, Mr. Ross, close to me—they’d see right through me. They’d decide I didn’t belong after all.”

She took a breath.

“You reminded me of that life,” she said. “Of my father’s hands, rough from work. Of my mother’s worry over bills. Of nights when the power went out because we’d paid for food instead. I was… ashamed of that. So I treated you like the world had treated me back then. I pushed you to the edges of rooms. I kept you at tables near the kitchen. I made sure you were never in the pictures, because I was afraid that if you were, someone would put the pieces together and see that I was just… a girl from a trailer park in New Mexico pretending she belonged in Scottsdale.”

Her voice cracked openly now.

“I am so sorry,” she said. “Not just for what the family did to you, but for what I did. For how I made you feel small because I was terrified of anyone seeing how small I once felt. You did nothing to deserve that. You were… are… family. And I failed you.”

She wiped at her eyes, careful not to smear her makeup but no longer trying to hide the emotion.

Miles stepped forward, as if pulled by a tide stronger than his fear.

“Dad,” he said, voice rough. “I… don’t have an excuse.”

He looked around at the room—at his colleagues, his bosses, his investors—and then back at me. For a brief moment, he was once again the boy on the milk crate in my workshop, fingers smudged with oil, looking up at me with wide, earnest eyes.

“I let ambition… swallow my judgment,” he said. “Every time Alicia made a cutting remark or seated you somewhere off to the side, I told myself it was just… logistics. Just optics. I told myself I was protecting your feelings by not making a scene. Really, I was protecting myself. I was afraid that if I stood up for you, if I insisted you be at the main table, people would look at me differently. That they’d see you—a clockmaker from Flagstaff, a man who worked with his hands—and decide I was less… sophisticated. Less worthy of their respect. So I chose silence.”

He swallowed hard.

“I chose silence over decency,” he said. “Again and again. I failed you. As a son. As a man. And I am so, so sorry.”

His hand trembled as he reached out, fingers hovering near my arm, not quite daring to land.

Years of distance sat between us like a long conference table stacked with unspoken apologies. But in that moment, I felt something shift—like a gear that had been out of alignment for years finally clicking into place.

I rose slowly from my chair.

My knees complained, my back reminded me I was not the man I’d been when I’d first drawn those designs for Davenport. But my voice, when it came, felt steady.

“I’m not here to destroy anyone,” I said. “I didn’t come tonight expecting any of this. I thought I was coming to sit behind a plant, drink ginger ale, and hope for a few minutes with my grandson.”

A faint, uneasy chuckle moved through part of the room. I let it pass.

“I did work for this company a long time ago,” I continued. “Work that helped you build something much bigger than I ever imagined. When my wife was sick, I took whatever jobs I could find. I signed whatever contracts was put in front of me because I didn’t have the time or money to fight. I let my pride take a back seat to survival.”

I looked at Richard.

“You took advantage of that,” I said, without anger, just simple truth. “You’ve admitted it. That’s more than some men would do. But a confession is only the first turn of the key. It doesn’t make the clock start on its own.”

I let my gaze move to Alicia, then to Miles.

“You both hurt me. Not with one grand action, but with a thousand little ones. Doors not opened. Seats not saved. Introductions not made. You turned me into an accessory to your life when I had been the foundation of your son’s. That’s not easy to live with. But… I’m tired of living inside old wounds.”

I turned slightly, so I could see Evelyn too.

“I want what’s owed to me,” I said. “But not just for me.”

The room tensed again, a collective breath held.

“So here is what I propose,” I went on. “Here are my terms, and they are not negotiable.”

The businessman in me—a man I had almost forgotten I’d once been, back when I’d drawn those designs and believed they might matter—rose to the surface.

“First,” I said. “The revenue share tied to the division built on my original work should be calculated, fairly and transparently, from the date it became profitable. Whatever portion can reasonably be attributed to that foundational design—your accountants and Ms. Hart’s team can figure that out—I do not want that money to pad my retirement. I want it to fund a vocational scholarship program in my wife’s name. A fund for young people in Arizona and across the United States who work with their hands. For mechanics. Electricians. Plumbers. Clockmakers, even, if any are left. People who build and fix the actual bones of this country, but who are too often told that their work is lesser because they don’t wear suits to do it.”

I heard a murmur of approval from one corner of the room. Maybe it was my imagination. Maybe it was someone from a family that remembered that kind of struggle.

“Second,” I said. “I want a formal advisory role on your board. Not a ceremonial title you put on a slide and forget about. A seat at the table. I’ve spent my life understanding how systems behave—mechanical, human, and otherwise. The voices in a room like that shouldn’t all come from the same neighborhoods, the same schools, the same golf clubs. You don’t just need diversity in your marketing materials. You need it in your decision-making.”

Several executives shifted in their seats. They weren’t used to being told they “needed” anything from a man whose jacket probably cost less than their tie. Evelyn, however, smiled faintly, approving.

“Third,” I said, turning to look directly at Miles and Alicia, “I want you to attend family therapy. Together.”

A few people blinked. One of the younger guests snorted quietly, then froze when his date shot him a look.

“I don’t say that because it’s fashionable,” I said. “I say it because my grandson deserves to see you work through this with help, not just pretend it never happened once the party’s over. He needs to see a model of strength that includes admitting when you’re wrong and learning how to do better.”

I looked at Alicia.

“And you,” I said gently but firmly, “will complete community service hours at the same shelter you’ve been donating canned goods and old clothes to without ever walking through the front door. Not as a photo opportunity. Not as a chairwoman. As a volunteer. You can file paperwork, serve meals, sit and listen to people whose lives look more like the one you came from than the one you’re in. You might find that facing that fear makes it smaller.”

Her mouth trembled, but she nodded slowly, something in her posture softening.

“Finally,” I said, and this was the one that had the most weight for me personally, “I want unlimited time with my grandson that isn’t governed by your schedules and your optics. I don’t mean I want to take him out of school or derail his life. I mean I want to see him without having to ask weeks in advance or worry that some event will push me off the calendar. I want him to come to Flagstaff when he wants, to sit in my workshop, to learn how things tick. I want to be a real part of his life, not a prop rolled out for holidays when it’s convenient.”

I let my hands fall to my sides.

“That’s what I need to sleep at night,” I said. “Not revenge. Not headlines. Just… respect. For my work. For my life. For my family.”

The room was utterly still.

Then, slowly, Alicia straightened her shoulders, not in defiance—but in acceptance.

“I’ll do it,” she said. “All of it.”

Her voice quivered but held.

“I’ll go to therapy,” she went on. “I’ll volunteer at the shelter. Not… as punishment. As… correction. I don’t want Liam to grow up with the same fear I’ve been carrying in my chest since I was a little girl waking up every morning afraid the car would be gone because we couldn’t make payments. I don’t want him to learn that the way to protect yourself is to hurt people who remind you of where you started.”

She looked at me, and for the first time since I’d met her, I heard something undeniably real in her tone.

“I’m sorry, Damen,” she said. “I can’t change what I did. But I can change what I do next.”

Miles stepped closer, finally letting his hand rest on my arm. His palm was warm and damp with nerves.

“I’ll go,” he said hoarsely. “To therapy. To whatever meetings you want. I’ll fight for that board seat for you. And I’ll make sure that any agreement we sign about the fund is more than just words. I… want to be better at this. At being your son.”

Beside the stage, the company’s general counsel was already pulling out his phone. The PR director was mentally assembling statements, trying to figure out how to frame this as a story of redemption instead of scandal. Investors from other states were calculating risk. Younger staff were watching with wide eyes, seeing their powerful bosses brought low by honesty.

Evelyn nodded, satisfied.

“Redstone will support the establishment of the fund,” she added. “And we’ll make sure the advisory role is written into the partnership agreements. Transparency is good for business, Mr. Davenport. So is making things right.”

Richard closed his eyes again, then opened them, looking directly at me.

“I agree,” he said simply. “To all of it.”

In the weeks that followed, the promises made that night did not evaporate under the fluorescent lights of conference rooms, as such promises sometimes do.

Lawyers from Davenport Industries, Redstone Capital, and an independent firm drafted documents that put everything into writing. Numbers were crunched, sometimes heatedly. Accountants argued over percentages. But eventually, a revenue share was calculated—a portion of profits from the division that had grown from my old design was set aside.

The “Ellen Ross Vocational Fund” was born, named after my wife.

It started as a line in a contract. Then it became a bank account. Then a brochure. Then, slowly, a reality: scholarships for young people in Arizona and across the United States, kids who wanted to attend trade schools, apprenticeship programs, technical colleges, but who didn’t have the resources. The first batch of applications came in from places I knew well—small towns, reservations, neighborhoods at the edges of big cities where opportunity doesn’t knock very loudly.

The board, to everyone’s surprise (including my own), welcomed my presence more than they resisted it. At first, some members shifted uncomfortably when I asked questions that cut through jargon to actual impact. They weren’t used to hearing someone say, “What does that mean for the people on the factory floor?” or “How does this make life better for the technicians installing these systems in schools and hospitals across the country?” in a room more accustomed to talking about market segments and shareholder value.

But over time, they realized something: seeing the world only from the top floor of a glass tower gives you a very limited view. I helped widen it, in my own small way.

As for therapy—it happened. Not because a public relations consultant thought it would look good, but because a seventy-two-year-old man had asked his son and daughter-in-law to sit in a room and tell the truth.

They hated the first session. Most people do. But they kept going. And bit by bit, they peeled back layers neither of them had wanted to admit were there. Old resentments. Deep fears. Patterns they’d learned from their own parents without even realizing it.

The community service at the shelter changed Alicia in ways she hadn’t anticipated. The first time she walked through the doors, pushing a cart of folded clothes without a camera in sight, she felt like she was stepping into a memory. The smells were the same—industrial cleaner, cheap coffee, the lingering scent of too many people in too small a space. She wanted to turn around.

But she didn’t.

A month later, she told me about a woman she’d sat with in the cafeteria, a mother holding a sleeping child whose hair was still damp from the shelter’s showers.

“She reminded me of my mother,” Alicia said quietly. “Her eyes, the way she kept checking the door, like someone might tell her she had to leave. I realized I’d spent my whole life trying to outrun that feeling. And in the process, I’d become the person I used to be afraid of.”

She shook her head.

“I don’t want to be that person anymore,” she said.

And Liam—well, Liam got what I asked for.

We settled into a routine that felt as natural as the ticking of my workshop clocks. Once or twice a month, sometimes more often when school allowed, he’d come up to Flagstaff for the weekend. Sometimes Alicia would drive him halfway and meet Miles there. Sometimes they’d make the whole trip together, and I’d watch with a quiet, cautious hope as they walked into my house as a family that felt more authentic, less like actors in a play.

One afternoon, months after the gala, I sat at my workbench with Liam at my side. Sunlight filtered through the window, cutting across the room in clean rectangles. Dust motes drifted lazily in the beam, floating in and out of existence.

On the bench before us lay an old clock, its case worn, its face cracked but repairable. The movement inside needed cleaning—years of neglect had left a gummy residue on the gears, slowing everything down.

Liam held a small brush in his hand, the same kind I’d used on Evelyn’s car that night on the interstate. His brow furrowed in concentration as he carefully cleared debris from between the teeth of a gear.

“Easy,” I said. “Let the bristles do the work. You don’t need to force it.”

He worked a little more gently. The metal glinted under the light as the grime gave way.

“Grandpa?” he asked after a while, not looking up. “Why do clocks matter so much to you?”

I leaned back on my stool, considering the question.

“I like that they tell the truth,” I said. “A clock doesn’t pretend. If it stops, it stops. If it’s slow, it’s slow. You can’t talk it into doing its job. You have to fix what’s wrong. Clean it. Adjust it. Take responsibility for what you’ve neglected.”

He nodded, absorbing that.

“And I like,” I added, “that they remind me every moment has value. When you sit with a clock, taking it apart, putting it together, you realize how many tiny pieces have to work together for something to keep time properly. Every tooth on every gear matters. If you let someone else tell you your part doesn’t count—if you let them decide your worth—you start to lose track of your own time. It slips through your fingers while you’re busy trying to fit into their schedule.”

He looked up at me then, eyes serious in a way that made him look older than eight.

“Is that what happened to you?” he asked. “Before. At the party?”

I thought about the years in the corner tables, the small indignities accepted in the name of peace. The quiet ways I’d let other people decide where I did and didn’t belong.

“It happened for a while,” I said. “I started to shrink myself to fit inside someone else’s world. I forgot that I had a right to take up space in my own story. But then…” I smiled. “Then I remembered. I realized respect isn’t something you wait for someone to hand you like a party favor. It’s something you claim when you decide you’re done apologizing for existing.”

He considered that. It was a lot for a child, but children are better at absorbing truths than some adults give them credit for.

He set the brush down, carefully, and turned the key on the clock’s mainspring, just enough. The movement took the energy, the gears engaged, and slowly, then steadily, the ticking began.

Tick. Tock. Tick. Tock.

A sound as old as any I’d ever known. A sound that carried every moment I’d lived: the years with my wife, the long nights in hospital rooms, the afternoons in the workshop with a young boy who would one day forget and then remember who his father was.

We sat there in the late afternoon light, listening to the clock find its rhythm again.

I felt something inside me settle, a long-awaited alignment. The gears in my own life—scattered, misused, neglected—had finally been cleaned, reset, set back into their rightful places. The man who had been pushed into the shadows of ballrooms and hidden behind plants had stepped into a different kind of light.

Not the glare of chandeliers in Scottsdale. Not the flash of cameras at corporate events. A quieter light. The kind that filters through pine branches in Flagstaff. The kind that falls across a workbench and a boy’s earnest face as he learns how to take care of the things that matter.

Dignity, I realized, doesn’t come from a title on a door or a balance in a bank account. It comes from standing tall in the truth of who you are, even when others have spent years trying to convince you you’re smaller than that.

Even after decades of being placed at the little tables near the kitchen, after years of being introduced as an afterthought, after countless tiny reminders that I was not the kind of man certain people wanted in their photographs, I had finally stepped back into my proper size.

I was a clockmaker from Flagstaff, Arizona. A widower who had loved his wife deeply. A father who had failed and been failed and had chosen, finally, to repair rather than discard. A grandfather whose hands, scarred and steady, guided a new pair of smaller hands through the careful work of putting things right.

And no one—not an old business titan, not an anxious daughter-in-law, not a room full of investors—could take that away again.

The gears inside me had finally settled into place, steady and sure, ticking toward whatever time I had left with a sound I could recognize as my own.

News

I was at TSA, shoes off, boarding pass in my hand. Then POLICE stepped in and said: “Ma’am-come with us.” They showed me a REPORT… and my stomach dropped. My GREEDY sister filed it so I’d miss my FLIGHT. Because today was the WILL reading-inheritance day. I stayed calm and said: “Pull the call log. Right now.” TODAY, HER LIE BACKFIRED.

A fluorescent hum lived in the ceiling like an insect that never slept. The kind of sound you don’t hear…

WHEN I WENT TO MY BEACH HOUSE, MY FURNITURE WAS CHANGED. MY SISTER SAID: ‘WE ARE STAYING HERE SO I CHANGED IT BECAUSE IT WAS DATED. I FORWARDED YOU THE $38K BILL.’ I COPIED THE SECURITY FOOTAGE FOR MY LAWYER. TWO WEEKS LATER, I MADE HER LIFE HELL…

The first thing I noticed wasn’t what was missing.It was the smell. My beach house had always smelled like salt…

MY DAD’S PHONE LIT UP WITH A GROUP CHAT CALLED ‘REAL FAMILY.’ I OPENED IT-$750K WAS BEING DIVIDED BETWEEN MY BROTHERS, AND DAD’S LAST MESSAGE WAS: ‘DON’T MENTION IT TO BETHANY. SHE’LL JUST CREATE DRAMA.’ SO THAT’S WHAT I DID.

A Tuesday morning in Portland can look harmless—gray sky, wet pavement, the kind of drizzle that makes the whole city…

HR CALLED ME IN: “WE KNOW YOU’VE BEEN WORKING TWO JOBS. YOU’RE TERMINATED EFFECTIVE IMMEDIATELY.” I DIDN’T ARGUE. I JUST SMILED AND SAID, “YOU’RE RIGHT. I SHOULD FOCUS ON ONE.” THEY HAD NO IDEA MY “SECOND JOB” WAS. 72 HOURS LATER…

The first thing I noticed was the silence. Not the normal hush of a corporate morning—the kind you can fill…

I FLEW THOUSANDS OF MILES TO SURPRISE MY HUSBAND WITH THE NEWS THAT I WAS PREGNANT ONLY TO FIND HIM IN BED WITH HIS MISTRESS. HE PULLED HER BEHIND HIM, EYES WARY. “DON’T BLAME HER, IT’S MY FAULT,” HE SAID I FROZE FOR A MOMENT… THEN QUIETLY LAUGHED. BECAUSE… THE REAL ENDING BELONGS TΟ ΜΕ…

I crossed three time zones with an ultrasound printout tucked inside my passport, my fingers rubbing the edge of the…

“Hand Over the $40,000 to Your Sister — Or the Wedding’s Canceled!” My mom exploded at me during

The sting on my cheek wasn’t the worst part. It was the sound—one sharp crack that cut through laughter and…

End of content

No more pages to load