The courtroom smelled like old paper, floor wax, and somebody’s cheap cologne sweating under broken air conditioning.

Heat clung to the wood-paneled walls of Fulton County Superior Court, Courtroom 4B, turning every breath into something you had to earn. The ceiling fans spun like they were trying, like they cared, but the air stayed thick, heavy—thick enough that whispers felt loud.

Then Sterling Thorne made it thicker.

He stood in a $3,000 suit that looked like it had been stitched directly onto his ego, and he wore his confidence the way some men wore wedding rings: as proof that the world belonged to him. He didn’t move like a lawyer. He moved like a landlord walking an apartment he planned to gut, deciding what stayed and what got tossed to the curb.

His client, Preston Vain—heir to the Vain Real Estate empire—sat at the defense table with the lazy boredom of a man who had never worried about consequences in his entire thirty years. He inspected his cuticles. He checked his reflection in his phone. He looked like the type who thought money made him immune to gravity.

He was on trial for siphoning four million dollars out of a veterans’ pension fund.

The prosecutor, David Chen, had dark circles beneath his eyes and the clipped urgency of a man who knew he was fighting more than a case. He was fighting a machine. Every time Chen tried to build momentum, Thorne cut him off like a blade.

“Objection,” Thorne snapped, his voice cracking through the humid air. “Badgering. Hearsay dressed up like evidence. Pathetic.”

Judge Harlon Ford—late sixties, skin like crumpled parchment, hands that had banged a gavel so long they sometimes forgot how to rest—peered over his glasses with the slow exhaustion of someone trapped in a three-week trial where one side treated the rules like suggestions.

“Sustained,” the judge muttered. Then to Chen: “Counselor. Watch your line of questioning.”

Thorne smirked. Not because he’d won an objection—he won objections the way some people breathed—but because he needed the room to remember whose theater this was.

He scanned the jury, then the gallery.

A few bored retirees sat scattered like forgotten props. A City Chronicle reporter typed with half an ear, waiting for a quote worth ink. A court clerk worked her keys in steady, practiced clacks. A bailiff with a belly and tired eyes—Davis—shifted his weight near the side wall, looking like a man who’d rather be anywhere else.

And in the back row of the gallery, behind the mahogany railing and the invisible line of who mattered and who didn’t, sat a sixteen-year-old girl with a notebook open on her lap.

Jasmine Reynolds.

People called her Jazz.

She wore a neatly pressed navy blazer over a white T-shirt, and her backpack strap was looped around her wrist like she’d been taught to keep her belongings close. Her pen moved fast, writing what she observed. She wasn’t there to cause trouble. She was a junior in high school, AP Civics, required to log ten hours of court observation for her semester project. She’d picked this trial because she wanted to be a prosecutor one day. She wanted to understand how power performed itself in public.

She was getting an education no textbook could give her.

Thorne’s eyes narrowed.

In his paranoid worldview, nobody took notes unless they were a threat. Nobody sat quietly unless they were plotting. He saw youth, he saw melanin, he saw a pen scratching across paper—and his mind did what minds like his always did.

It invented danger to justify cruelty.

He leaned down, murmuring to Preston Vain. “That girl back there. Do you know her?”

Preston glanced over his shoulder once, barely interested. “Never seen her. Probably some staff kid waiting for a ride.”

Thorne’s jaw flexed. “She’s writing down everything. And she’s on her phone.”

Jazz wasn’t texting. She was checking the time because her mom had promised to pick her up at recess, and she didn’t like being late. It was 2:58 p.m. Recess was at three.

Thorne straightened, buttoning his jacket like he was preparing for war.

He needed a distraction. Chen’s cross-examination was circling closer to the Cayman accounts, and Preston looked guilty in the way rich men get guilty—subtle, almost bored, like guilt was an inconvenience.

Thorne needed the room to look somewhere else.

He found his punching bag.

“Your Honor,” Thorne boomed, interrupting Chen mid-sentence. “I must pause these proceedings immediately.”

The words hit the room like a slap. Even the stenographer’s fingers hesitated.

Judge Ford blinked slowly. “On what grounds, Mr. Thorne?”

Thorne lifted a manicured finger and pointed—directly—at the back row.

At Jazz.

“Because,” he said, voice rising, “it appears we have a security breach. That individual has been recording these proceedings on her mobile device and signaling someone outside the courtroom. I believe she is coaching witnesses.”

Jazz froze so hard her pen hovered above the page like it couldn’t decide whether to exist.

For one sick second, she looked left and right, as if the accusation might belong to someone else. Then she realized his finger was still aimed at her chest.

“Me?” she whispered, the word barely making it past her throat.

“Stand up,” Thorne barked, already walking away from the defense table. “Don’t play innocent. Stand up and hand over that phone.”

Bailiff Davis’s face tightened. He took a reluctant step forward, then stopped, like his body was arguing with his job.

“Mr. Thorne,” Davis said carefully, “she’s just a kid.”

“I don’t care if she’s a Girl Scout,” Thorne snapped. “She is compromising my client’s right to a fair trial.”

The room shifted. The jury leaned forward. The reporter’s eyes lit up. Judge Ford’s mouth opened, then closed again, as if he couldn’t quite believe what he was watching.

Jazz stood slowly, trying to keep her hands steady. Her phone was tucked in her palm. Her heart hammered loud enough she was sure the jurors could hear it.

“I—I wasn’t recording,” she said. “I’m a student. I’m here for a project.”

Thorne laughed, cruel and sharp. “A project,” he repeated like it was a dirty word. He turned to the jury, spreading his arms. “You hear that? She treats this court like a bus stop. Like a hangout. That is the lack of respect we are dealing with.”

He turned back, and his expression changed. The smile vanished. Something uglier came in behind it.

He pushed through the swinging gate of the bar—crossing a boundary lawyers weren’t supposed to cross—and walked into the public gallery like the rules didn’t apply to him.

He stopped close enough that Jazz could smell his cologne and the sour edge of coffee on his breath.

“You don’t belong here,” Thorne hissed, loud enough for everyone to hear. “This is a place of law. Of sophistication. It is not a place for loiterers. Not for street kids. You are a disruption. You are a blight.”

“Mr. Thorne,” Judge Ford warned, banging the gavel. “That is enough.”

“It is not enough,” Thorne snapped back without even turning to the bench. He was performing now, feeding off the tension, making sure every pair of eyes stayed on him. “I want her removed. I want her phone confiscated and analyzed. And I want her held in contempt.”

He leaned closer, voice dropping to a threat disguised as procedure.

“Give me the phone,” he said. “Now. Or I will have Bailiff Davis drag you into a holding cell where you can think about your little espionage game.”

Jazz backed up until the wooden bench pressed into her legs. Her hands trembled, but she did not cry. She had been taught, in ways she didn’t even have words for yet, that tears sometimes made things worse.

“You have no right,” she said, voice shaking but clear. “I haven’t done anything wrong. You’re bullying me because you’re losing.”

A gasp rippled through the room.

Thorne’s face went blank for half a beat, like his brain couldn’t compute what had just happened. Then it contorted into pure fury.

A teenager. A Black teenager. In open court. Talking back to him.

His ego couldn’t swallow it.

“You insolent—” he started, voice rising.

Judge Ford’s gavel hit again. “Mr. Thorne—”

“Bailiff!” Thorne shouted over the judge like the bench was background noise. “Arrest her. She is disturbing the peace. She is obstructing justice. Get her out of my sight before I sue her family into the dirt.”

Davis looked at the judge, uncertain.

The judge looked… paralyzed. Tired. Outmatched by a man who had spent two decades bullying courtrooms into silence.

Jazz’s throat tightened. She grabbed her backpack with one hand.

“I’m leaving,” she said, trying to keep dignity in her voice. “I don’t need to be arrested. I’m leaving.”

“Oh, you aren’t going anywhere,” Thorne snarled, reaching out.

His fingers aimed for her arm.

“Don’t touch me,” Jazz snapped, recoiling.

And that was when the doors exploded open.

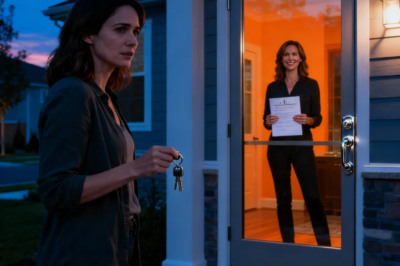

Not a polite opening. Not a cautious entry. The double oak doors at the back of Courtroom 4B flew wide with calculated force and slammed against the walls so hard the hinges shuddered.

The sound was a gunshot made of wood.

Every head in the room snapped around.

In the bright rectangle of hallway light stood a woman—tall, broad-shouldered, built like discipline. She wore a tailored black tactical suit and heavy boots that made the floor seem to feel her coming. Her hair was pulled back into a severe, no-nonsense bun, and her posture was the kind you didn’t question if you had good survival instincts.

On her belt: handcuffs, radio, badge.

Not a local badge. Not a security badge.

A federal star catching fluorescent light.

UNITED STATES MARSHALS SERVICE.

She didn’t hurry.

She marched.

Her calm was terrifying.

Her eyes locked on Sterling Thorne like laser sights.

The courtroom went so silent you could hear the struggling air conditioner attempting to restart.

“Mom,” Jazz breathed, and relief almost buckled her knees.

The woman didn’t stop until she was behind her daughter, then she shifted, placing herself physically between Jazz and Thorne.

She scanned Jazz quickly—eyes on her face, hands, arms—checking for injury without making it a scene.

“You okay, Jasmine?” she asked, voice low, controlled, a smooth alto with the dangerous undertone of a growling engine.

“He—he tried to take my phone,” Jazz whispered. “He said he was going to put me in a cell.”

The woman turned her head slowly.

And looked at Sterling Thorne.

For the first time in his career, Thorne looked uncertain. He adjusted his tie, trying to recall the posture that usually made people shrink.

Arrogance was a hard habit to break.

“Finally,” he scoffed, but his voice lacked the earlier boom. “You the mother? You should be ashamed. Your daughter has been disrupting proceedings. I was instructing the bailiff to take her into custody.”

The woman stared at him.

Didn’t blink.

Didn’t flinch.

“You were instructing the bailiff,” she repeated.

She took one step closer. Thorne took a step back without meaning to.

“Yes,” he said quickly, attempting to re-inflate. “I am Sterling Thorne. Lead counsel. And I demand—”

“You demand?” she cut in.

She reached into her vest and pulled out a folded document.

“That’s funny,” she said, voice carrying to the back row. “Because usually when people see me, they stop making demands and start calling their lawyers.”

Thorne’s mouth tightened. “Judge Ford,” he snapped, pivoting, “hold this woman in contempt. You can’t barge in here with—”

The woman glanced toward the bench with a crisp nod that carried respect without submission.

“Judge Harlon Ford,” she said. “United States Marshal Viola Reynolds. Badge number 492. Apologies for the interruption, Your Honor, but I’m operating under authority of the Department of Justice.”

Then she turned back to Thorne.

“And I didn’t come here just to pick up my daughter.”

The words hung.

The jury’s eyes widened. The reporter’s fingers flew. Preston Vain sat up straighter for the first time all day.

Thorne’s confidence cracked. “What is this?” he demanded.

Marshal Reynolds smiled.

It was not a kind smile.

“The kind of thing,” she said, “that ends with you in handcuffs, counselor.”

The courtroom erupted in whispers.

Preston Vain’s gaze darted to the exit sign like it might save him.

Viola lowered her voice—quiet enough that only Thorne and Jazz could hear, but sharp enough to cut.

“You yelled at my child,” she said. “You tried to use your influence to terrify a sixteen-year-old girl. You made a mistake, Sterling. You thought you were the shark.”

She tapped the star lightly on her chest.

“But you swam into the ocean.”

Thorne swallowed. Hard.

“A warrant?” he managed, voice cracking. “For me?”

Judge Ford was no longer looking at Thorne. He was looking down at the document Viola had placed on the bench. His hands trembled slightly as he adjusted his glasses and read the header.

U.S. DISTRICT COURT — NORTHERN DISTRICT OF GEORGIA.

SEALED INDICTMENT — UNSEALED PURSUANT TO ORDER.

His eyebrows shot up.

“Mr. Thorne,” Judge Ford said, voice suddenly firm, “I suggest you be quiet.”

“Be quiet?” Thorne sputtered, face flushing. “I am representing a client in a high-profile embezzlement trial. I will not be silenced by—by some federal—”

Viola unhooked a small ring of keys from her belt. The metal jingled softly in the hush.

It was a tiny sound.

But it did something to the room. It reminded everyone that she was not here to argue.

She turned her head to Bailiff Davis. “Davis,” she said.

“Yes, Marshal,” he answered automatically, eyes wide.

“Lock the doors,” she ordered. “Nobody leaves. Not the jury, not the press, and definitely not Mr. Thorne.”

Thorne’s voice hit a new pitch. “This is unlawful imprisonment! I know senators. I know the governor. I will destroy you—”

Viola’s gaze stayed steady. “Sterling,” she said quietly, almost tired, “stop talking. Every word you say is on the transcript, and you are going to hate yourself for it.”

She stepped toward the center of the courtroom with the ease of someone who had walked into worse rooms than this one. She didn’t need theatrics. Her presence was the theater.

“Your Honor,” she said, “the document you’re holding is a federal arrest warrant issued this morning. It accompanies an indictment returned by a grand jury.”

Thorne’s face went pale.

“What charges?” he blurted, unable to stop himself. “I have a right to know.”

Viola turned slowly. “Racketeering,” she said. “Wire fraud. Money laundering. Conspiracy to commit witness tampering.”

Preston Vain’s hand tightened on the table edge.

Judge Ford’s mouth went tight. “Mr. Thorne,” he said, “is this true?”

“It’s a lie,” Thorne hissed, sweat beading on his forehead. “My firm is impeccable.”

“Your firm?” Viola corrected, stepping closer. “Your firm is a laundromat, counselor. And the machine just broke.”

Thorne tried to laugh—high and nervous. “I’m the attorney of record. I’m doing my job.”

“We have the logs,” Viola said, pulling a second document from her vest. “Encrypted messages sent from your smartwatch. Time stamps. Pattern. Every time the prosecution raised the Cayman accounts, you tapped.”

She mimicked it—two taps, a pause, one tap.

“And minutes later,” she continued, “funds moved. You weren’t just defending Preston Vain. You were helping him hide money during a live trial.”

The courtroom cracked open.

The reporter from the City Chronicle typed so fast his hands blurred.

The jury whispered furiously.

Judge Ford banged the gavel, but it sounded more like procedure than control.

Thorne shook his head wildly. “Entrapment. Conspiracy. I invoke—” His voice broke. “I need a lawyer.”

Viola’s expression didn’t change. “You are a lawyer,” she said. “Or you were.”

She turned to Jazz. “Jasmine. Come here.”

Jazz hesitated, then stepped forward through the gate, past the stunned bailiff, past the prosecution table, until she stood beside her mother.

“Mr. Thorne wanted your phone,” Viola said.

“Yes,” Jazz answered.

“Show the court what you were writing.”

Jazz opened her notebook and held it up.

It wasn’t text messages. It wasn’t a recording. It was a hand-drawn diagram of the courtroom: jury box, witness stand, counsel tables. Little notes in the margins. Observations. Arrows.

“I was tracking the jury’s reactions,” Jazz said, voice steady now. She looked at the judge, then at the jury, and she didn’t shrink. “For my project, I noticed Juror Four kept looking at Mr. Thorne every time he adjusted his tie. And I noticed Mr. Thorne would nod back. I wrote down, ‘Is there a signal?’ I wasn’t texting. I was analyzing.”

Thorne stared at the notebook like it was a mirror showing him the part of himself he’d pretended didn’t exist.

The color drained from his face completely.

The teenager he’d tried to humiliate—his chosen target—had seen the pattern by simply paying attention.

Viola leaned in, voice a whisper meant for only him.

“Karma,” she said, “is a mother.”

Judge Ford’s voice cut through the heat like granite. “Bailiff Davis. Secure Mr. Thorne.”

“You can’t do this!” Thorne shrieked as Davis moved in.

Davis’s grip was firm—too firm for a man who was supposedly impartial. It carried the weight of years swallowing disrespect.

Thorne twisted, desperate, looking for salvation.

“Preston!” he shouted, turning to his client. “Tell them. Tell them this is nonsense.”

Preston Vain—who had never faced consequences before—looked at the marshal’s star, then at Judge Ford’s furious face, then at Thorne’s sweating panic.

He made a calculation the way rich men always did: fast, selfish, survival-based.

“I don’t know what he’s talking about,” Preston said smoothly, standing. “I had no idea my attorney was engaging in illegal activity. Frankly, I feel like a victim.”

Thorne’s jaw dropped.

“You gave me the codes,” Thorne sputtered. “You told me to move the money.”

“Allegedly,” Preston said, stepping back. “I think I need new counsel.”

Viola’s head tilted. “Not so fast,” she said.

Preston blinked. “Excuse me?”

Viola signaled to the back. Two deputy marshals stepped in carrying evidence boxes.

“You’re going to meet your new attorney,” Viola told Preston, “at a federal detention center.”

The sound of cuffs clicking around Preston Vain’s wrists was the loudest, cleanest punctuation the courtroom had heard in weeks.

Outside the courtroom, the news moved faster than justice ever did.

By the time Thorne was hauled through the marble corridor—hands cuffed, suit wrinkled, face twisted in disbelief—there were already people with cameras running toward the exits. Word had leaked the way scandal always did: instantly, hungrily.

Sterling Thorne’s usual victory walk down that corridor was famous. For twenty years, he’d strutted past portraits of old judges like he owned the building, surrounded by sycophants, smiling for cameras, spinning narratives that made wolves look like saints.

Today he walked it in handcuffs.

Outside the courthouse, the air was cooler, but the atmosphere was electric. Flashbulbs popped. Microphones lunged.

“Marshal Reynolds! Is it true the defense attorney was moving money from inside the courtroom?”

“Jasmine! Did he threaten you?”

“Are the feds raiding Vain Real Estate right now?”

Viola lifted one hand.

The crowd, sensing the same authority that had silenced a courtroom, quieted in uneven waves.

“We have no comment on the ongoing federal investigation,” Viola said, voice clear against the wind. “But let this be a reminder: bullying a child inside a courtroom isn’t just misconduct. It’s the behavior of someone who believes he’s above the law.”

She guided Jazz toward the black government SUV waiting at the curb.

“And today,” Viola finished, “we proved he isn’t.”

Jazz slid into the passenger seat, adrenaline shaking out of her hands. She looked back through the window.

Thorne was being pushed toward a cruiser. He looked smaller without his briefcase. Without his practiced smile. Without the room bending to him.

He tried one last threat—old habit, dying instinct.

“Get that camera out of my face!” Thorne snarled at a local news cameraman. “Do you know who I am? I will sue—”

“Save it for the judge,” someone shouted back.

The clip went viral before the cruiser even left the curb. By the time Viola and Jazz pulled into their driveway, Sterling Thorne’s face was everywhere—sweaty, furious, cuffed. A man exposed. A man unmasked.

But the real devastation was happening forty floors up, in a glass boardroom at Thorne, Vain & Associates.

The senior partners sat around a polished table, their eyes cold, their phones buzzing with messages from clients who suddenly remembered they had “other options.”

Nobody asked how to save Sterling.

They asked how to cut him loose.

“He’s toxic,” Harrison Blackwood, the co-founder, said flatly. “The feds are seizing servers. Invoke the morality clause.”

A junior partner swallowed. “Sterling wrote that clause.”

“Then he should’ve read it,” Blackwood replied. “Freeze his equity. Cancel his cards. Change the locks to his office. If he makes bail, I don’t want him within five hundred feet of this building.”

Sterling Thorne did not make bail.

At his arraignment the next morning in federal court downtown, the magistrate judge—Alice Holloway—peered down at him with a cold familiarity. Thorne had insulted her publicly years ago, calling her “soft.” Karma had a patient memory.

“Given substantial evidence of flight risk,” Judge Holloway said, “including offshore access attempted during ongoing proceedings, and evidence of multiple passports, bail is denied.”

“Denied?” Thorne gasped. “Your Honor, I have a home in the Hamptons—”

“You have a holding cell,” Judge Holloway corrected. “Next case.”

The first weeks in custody stripped him faster than any headline.

The man who drank imported sparkling water drank rust-tasting tap water. The man who wore Egyptian cotton wore scratchy polyester. The man who used to snap his fingers for assistants now had to ask politely for a second blanket.

And the worst part wasn’t the discomfort.

It was the silence.

His wife—Meredith, a socialite who’d loved his power more than his soul—filed for divorce three weeks after his arrest. She didn’t visit. She sent a process server. She took the house, the cars, the art collection, and she did it with the efficiency of someone removing a stain.

Thorne was left with nothing but time.

Time to replay the day he pointed at a girl in the back row like she was trash.

Time to realize he hadn’t even known her name.

The federal case that followed—United States v. Sterling Edward Thorne—didn’t open with fireworks.

It opened with grinding exposure.

Eight months after the incident in Courtroom 4B, Federal District Courtroom 12 was packed. Not just press now. Lawyers from rival firms. Former associates. Paralegals whose eyes held old fear and fresh satisfaction. People who’d swallowed his bullying for years because they thought he was untouchable.

They came to watch the king fall.

At the front row behind the prosecution table sat Marshal Viola Reynolds, shoulders squared, face composed. Beside her sat Jazz, no longer the trembling student. She wore a blazer she’d purchased with her own internship money, and her posture was quiet proof that intimidation had failed.

Sterling Thorne chose to represent himself.

It was the kind of decision made by a man who mistook arrogance for strategy. He believed no one could speak for him better than he could. He believed he could charm a federal jury the way he’d charmed donors and partners for two decades.

He was wrong.

Judge Thomas Wright—a former Marine, seventy years old, face carved from granite—presided with the patience of a man who had none. He did not tolerate performance. He tolerated evidence.

On the final day of trial, Thorne stood at the podium cross-examining the government’s forensic financial expert, Dr. Evelyn Carter.

“You claim these transfers were authorized by me,” Thorne sneered, voice raspy from months of confinement. “Isn’t it true anyone with a passcode could have sent them? Isn’t it true I’m the victim of hacking?”

Dr. Carter adjusted her glasses calmly. “Mr. Thorne,” she said, “the transfers were authorized using a biometric pattern tied to your smartwatch—heart rate signature combined with a manual tap sequence. Unless someone severed your hand and wore it while tapping, it was you.”

A ripple of laughter escaped the gallery, quick and involuntary.

Thorne’s face turned a blotchy purple. “Speculation!” he shouted, slamming his fist down.

Judge Wright’s voice boomed. “Mr. Thorne. You will not slam my furniture. You will address the witness. One more outburst and you will be restrained. Do you understand?”

Thorne swallowed. “Yes.”

He sat down, smaller than he’d ever been in a courtroom.

Then the government called Jasmine Reynolds.

The room shifted. Necks craned. Even people who hated prosecutors leaned forward, hungry for the moment.

Jazz stood, walked past her mother, felt Viola’s hand squeeze her arm—brief, grounding—and then she stepped into the witness box.

“Do you swear to tell the truth?” the clerk asked.

“I do,” Jazz said.

Assistant U.S. Attorney Rachel Brooks guided her through the events of that day: the accusation, the humiliation, the threat, the moment the doors slammed open.

Then Brooks turned. “Your witness, Mr. Thorne.”

Thorne rose slowly. He buttoned his cheap suit jacket like it could restore his old power. He approached the witness stand with a predator’s muscle memory, trying to summon the intimidation that used to make grown men stutter.

“Miss Reynolds,” Thorne began, voice slick with fake warmth. “You look very nice today. Dressed up for your big moment.”

“Objection,” Brooks said. “Relevance.”

“Sustained,” Judge Wright grunted. “Move on.”

Thorne’s jaw clenched. “You claimed I was bullying you,” he pressed, leaning forward. “Isn’t it true you were disrupting proceedings? Using your phone in violation of rules?”

“I checked the time,” Jazz said calmly. “My mother was picking me up.”

“But you were writing notes,” Thorne snapped. “Notes about me. Spying. Who paid you? The FBI? The prosecution?”

“Nobody paid me,” Jazz replied. “I was a student observing the justice system. And I learned a lot.”

Thorne scoffed, and the old cruelty tried to rise again. “Oh, did you? And what did you learn, little girl?”

The phrase hit the room like poison.

Jazz leaned toward the microphone. She didn’t look down. She didn’t shrink.

“I learned some people think the law is meant to protect the weak,” she said, voice steady, ringing out. “And I learned men like you think the law is a weapon.”

Thorne’s eyes narrowed.

“You saw a Black teenager in the back row,” Jazz continued, “and you decided I was prey. You didn’t care whether I was innocent. You wanted to remind everyone you had power.”

“I was maintaining order,” Thorne snapped.

“No,” Jazz corrected, quiet but unbreakable. “You were maintaining fear.”

She paused. Let the words settle.

“But you forgot something, Mr. Thorne.”

His lip curled. “And what is that?”

“Fear only works,” Jazz said, “if people are afraid of you.”

The courtroom held its breath.

“I’m not afraid of you,” Jazz finished. “Not anymore. I look at you now and I don’t see a scary lawyer. I see a man facing consequences.”

A murmur rolled through the gallery like a wave.

Judge Wright banged the gavel once, but even his stern mouth threatened something close to satisfaction.

Thorne stood there a moment too long, searching the room for allies.

There were none.

“I have no further questions,” he whispered, and he sat down like gravity had finally remembered him.

Closing arguments were brutal.

Brooks painted Thorne as more than a thief—she called him a rot inside the system, a man who used law as a shield while he bled people dry. She spoke about veterans whose pensions were stolen, witnesses who were pressured, staff who were threatened, and a teenager in the back row who was treated like disposable because she was seen as powerless.

Thorne’s closing was a rambling mess of conspiracies and wounded ego that Judge Wright cut off when it became clear it wasn’t an argument—it was a tantrum.

The jury left at 2:00 p.m.

They returned at 3:15.

Seventy-five minutes.

In a complex federal racketeering case, a deliberation that short isn’t a sign of debate. It’s a sign of certainty.

“All rise,” the clerk called.

Thorne stood, trembling now. Sweat tracked down his temple.

“Mr. Foreman,” Judge Wright asked, “have you reached a verdict?”

“We have,” the foreman said.

“Read it.”

“On Count One—racketeering—we find the defendant guilty.”

Thorne flinched.

“On Count Two—wire fraud—guilty.”

His shoulders sagged.

“On Count Three—money laundering—guilty.”

His face twisted.

“On Counts Four through Eight—conspiracy to commit witness tampering—guilty.”

Each word felt like a nail.

Thorne’s knees weakened. He sat hard, burying his face in his hands—not crying for victims, not crying for the men whose retirement he’d stolen, but crying for himself, because he still couldn’t believe the universe was allowed to say no to him.

Judge Wright did not grant weeks for sentencing. He had reviewed the reports. He had heard the testimony. He was done with delay.

“Mr. Thorne,” he said. “Stand.”

Thorne rose slowly, pale and shaking.

“Do you have anything to say before sentence is imposed?”

Thorne’s eyes were red, wild. “Judge, please. I—I have anxiety. I need medical care. I can’t go to prison. I’ll die. House arrest. I have—”

“You have nothing,” Judge Wright cut in, voice ice. “Your assets will be seized for restitution.”

He leaned forward, hands folded.

“In my decades on this bench,” he said, “I have seen men commit violence with fists and guns. But I have rarely seen someone commit violence with influence the way you have. You took an oath to uphold the Constitution. Instead, you treated your license like permission to prey.”

He glanced toward the front row. Toward Jazz.

“That young woman,” Judge Wright said, “has more integrity than you demonstrated in twenty years.”

Thorne’s mouth opened, but no words came.

“For these crimes,” Judge Wright continued, “I sentence you to twenty-five years in the custody of the Federal Bureau of Prisons.”

“Twenty-five?” Thorne gasped, voice cracking. “That’s—”

“Then you should have thought about that,” Judge Wright said, unmoved. “Bailiff. Take him.”

Thorne panicked.

He tried to run—an awkward, stumbling scramble toward the rail, like escape was still an option if he moved fast enough. The attempt was pathetic, stripped of dignity by its own desperation.

Bailiff Davis stepped into his path.

Not with a tackle. Not with drama.

Just a wall.

Thorne ran into him and bounced off, hitting the floor hard. Davis looked down, expression blank.

“Get up,” Davis said.

Thorne was hauled to his feet, cuffed, and led out.

The courtroom watched him go with a quiet that felt like release.

Outside, autumn air cut crisp and clean. Leaves burned gold along the courthouse steps. Cameras waited, of course—they always waited. But Viola didn’t feed them. She guided Jazz through the crowd with the calm strength of a woman who understood that real victory didn’t require an audience.

They walked two blocks away, away from flashing lights, and sat on a bench in a small city park.

Viola exhaled, long and deep, and for the first time that day her shoulders lowered.

“You okay?” she asked.

Jazz stared at the courthouse in the distance. “I am,” she said slowly. Then, softer: “Is it weird that I feel… sad for him?”

Viola looked at her daughter with something like pride. “No,” she said. “That just means you’re human. Don’t confuse compassion with permission, though. He didn’t fall by accident. He climbed into that power and used it to hurt people.”

Jazz nodded.

Then she reached into her backpack and pulled out a thick cream-colored envelope.

Viola’s gaze locked on it instantly, the way moms do when they’ve been watching their kid fight for something.

The return address was embossed in blue ink.

Yale University.

Viola’s hands trembled as she took it. She didn’t speak. She just tore it open carefully, like the paper could shatter if handled wrong.

Jazz watched her mother’s eyes move across the letter.

Then Viola made a sound that was half laugh, half sob.

“Baby,” she whispered.

Jazz’s throat tightened. “What?”

Viola turned the letter so Jazz could see the words that changed everything:

It is with great pleasure that we offer you admission…

Jazz’s face crumpled, not from weakness—release. The kind of release you get when you realize the future is real and it wants you too.

Viola pulled her into a hug so fierce it felt like armor.

“Yale,” Viola breathed. “My baby’s going to Yale.”

Jazz laughed through tears. “I wrote my essay about it,” she said, muffled against her mother’s shoulder. “About that day. About how I want to be a prosecutor who fights for the people in the back row.”

Viola pulled back, held Jazz’s face between her hands.

“You’re going to be the best of them,” she said. “You’re going to change the world.”

Jazz smiled, shaky but bright. “I learned from the best.”

Years moved the way years do—fast when you look back, slow when you live them.

Sterling Thorne’s name turned from headline to cautionary tale. His old firm erased him like he was bad PR. His friends vanished. The world that had once bent around him found other suns to orbit.

Justice didn’t just punish him.

It replaced him.

Jazz left for college with a suitcase and a purpose. She called her mother often. She studied late. She learned how to argue without losing herself. She learned how to build a case like a bridge—strong enough to carry people who had been told their whole lives they didn’t matter.

Viola watched from a distance the way mothers do when their children become something larger than fear.

And one spring morning, years after the day in Courtroom 4B, Jazz walked into a courthouse again.

Same building. Same marble. Same echo in the hallway.

But she wasn’t sitting in the back row anymore.

She walked to the prosecution table with a briefcase heavy with files—names, lives, stories. She set it down carefully and looked up at the bench.

“All rise,” the bailiff called.

Jazz stood tall.

In the gallery, one woman sat in the back row, quiet, proud, her hair touched with gray now but her posture still steel.

Retired U.S. Marshal Viola Reynolds.

Jazz met her mother’s eyes and smiled.

The air conditioning in Courtroom 4B worked now. The air moved, cool and clean, like the building itself had learned something.

Jazz stepped forward when her case was called, voice steady, spine straight.

She wasn’t the girl someone tried to erase.

She was the law.

And this time, justice didn’t have to kick down the door.

It already had a key.

The courthouse doors didn’t close behind Sterling Thorne so much as they swallowed him.

One minute he was still trying to bark orders through clenched teeth, still throwing his name around like it could stop gravity—still looking for the old reflex in people’s faces, that automatic flinch that used to come when he raised his voice. The next minute he was gone down a side corridor, guided by hands that didn’t tremble for him and eyes that didn’t respect him.

And when the heavy door latched, the silence that followed didn’t feel empty.

It felt clean.

Inside Courtroom 4B, everyone sat in the aftershock like they’d just watched a building collapse and realized they were still standing. The jurors stared forward, trying to process the fact that they had entered that room believing they were there to decide a rich man’s guilt, and they’d ended up watching a different kind of trial—one where the loudest man in the room had been unmasked in real time.

Judge Ford’s gavel rested on the bench like an exhausted fist. He looked older than he had thirty minutes ago. Not because of time, but because something had cracked—a hard recognition that the court he’d spent decades protecting had been used like a stage for corruption.

Bailiff Davis stood with his hands clasped behind his back, posture straight in a way Jazz hadn’t seen earlier. It was like even his body understood the shift. He’d spent years watching power get away with behavior nobody would tolerate from ordinary people. Now he’d watched that power stumble and bleed.

The prosecutor, David Chen, sat with his hands folded tightly, as if he couldn’t trust them not to shake. He looked like a man who had been sprinting uphill for weeks and suddenly found the road flattened beneath his feet. He didn’t celebrate. Not yet. He just stared at the evidence boxes being carried out, and you could see his mind already rewinding, already replaying the case from the beginning, seeing where it had been rigged, seeing what had been hidden in plain sight.

Preston Vain—still cuffed—stood near the defense table with a look that tried to be offended but couldn’t quite find the energy. He was a man who had always believed consequences were for other people. Now the cold metal around his wrists forced him into the body of someone ordinary. It made his fingers awkward. It changed the way he held his shoulders. It made him blink too often.

He wasn’t bored anymore.

He was scared.

Jazz didn’t feel triumph the way she thought she might have. There was no rush of victory, no swelling music in her chest. What she felt was something steadier and stranger.

She felt seen.

For a few long minutes, it had been her on the edge of humiliation, her name replaced by assumptions, her body treated like a prop for a powerful man’s performance. Thorne had tried to turn her fear into entertainment. He’d tried to make the jury’s eyes land on her instead of on his client’s guilt.

And then her mother had walked in.

Not like a rescuer in a movie.

Like a fact.

Like a line in the law that had been waiting for the right moment to be drawn.

Viola Reynolds turned back to her daughter and softened just slightly, like she was allowing the “U.S. Marshal” part of herself to loosen enough for the “mom” to breathe.

“You ready?” Viola asked, voice low.

Jazz nodded, though her throat was still tight. “Yeah,” she said. Then, honest: “I think so.”

They moved toward the exit, but the courtroom had shifted into a new kind of attention. People watched them not like spectators, but like witnesses. It wasn’t admiration, exactly. It was recognition. The quiet recognition that one teenager had stood in the back row and refused to become small.

As Viola guided her down the aisle, Jazz heard someone behind her whisper, “That’s the girl.”

The girl.

As if she had been turned into a symbol in a single afternoon.

Jazz didn’t know how she felt about that. She didn’t want to be a symbol. She wanted to be a person who got to be in a courthouse without being treated like a suspect.

But symbols happened anyway. Especially in America. Especially to people who hadn’t asked.

They pushed through the doors into the hallway, and the air out there felt cooler, less sweaty with tension. Still, the building hummed with rumor. People leaned out of offices. Court staff moved faster. Phones rang. There was a tremor running through the marble bones of the courthouse—news traveling the way scandal always did, like electricity.

Halfway down the corridor, a man in a gray trench coat stepped out from the shadows near a bulletin board and lifted his hand politely.

“Marshal Reynolds,” he said, voice careful.

Viola’s hand hovered near her belt instinctively—not reaching, not threatening, just the quiet readiness of someone trained to survive.

“Yes?” she said.

“My name is Arthur Pendleton,” the man replied. “State Bar Association. Ethics committee.”

Viola’s posture eased by a fraction.

Pendleton looked worn in the way of people who spent their careers staring at the gap between what should be and what is. He nodded toward the door Thorne had vanished through.

“We’ve been trying to get him for a decade,” Pendleton said softly. “But nobody would testify about the intimidation. Everyone settles. Everyone is afraid.”

His gaze shifted to Jazz. Not predatory. Not hungry. Respectful. Like he understood how hard it was to be sixteen and standing in the blast radius of a powerful man’s collapse.

“We’re going to need a witness for disbarment,” he continued. “Not for the criminal case—you’ve got that. But to make sure he never practices again. Never consults. Never quietly resurfaces.”

Jazz swallowed. Her stomach tightened again, not with fear now but with the weight of what “witness” meant. She knew what it meant to be targeted. She’d tasted it.

Pendleton lowered his voice. “His allies will try to spin it,” he warned. “They’ll say you provoked him. That you’re part of a setup. They’ll come for you in the press.”

Jazz looked up at her mother’s star. She looked at her mother’s face—calm, steady, familiar strength.

Then she looked at Pendleton.

“I’ll do it,” Jazz said.

Pendleton blinked, surprised at how quickly the answer came.

Jazz’s voice didn’t shake. “He tried to make me feel ashamed for being in a courtroom,” she said. “He tried to turn the law into a weapon. I’m not letting him do that to the next person.”

Viola’s mouth lifted into something like pride.

Pendleton nodded once, solemn. “Thank you,” he said. Then he stepped back like he understood this moment wasn’t for him.

Viola wrapped her arm around Jazz’s shoulders gently. “Let’s go,” she murmured.

And as they reached the front doors, the courthouse greeted them with a wall of flashing lights.

Outside, the steps were crowded. Microphones jutted forward. Cameras glared. People shouted questions like they were throwing stones.

“Marshal Reynolds!”

“Did the defense attorney tamper with witnesses?”

“Is the billionaire going to federal prison?”

“Jasmine, did he threaten you?”

“Is this related to a bigger corruption ring?”

Jazz’s heart jumped, but Viola’s presence anchored her. The crowd’s noise hit Viola and seemed to break around her like water around a rock.

Viola lifted one hand, palm out.

It wasn’t a dramatic gesture. It was simple, controlled authority. The kind that made even hungry reporters pause.

“We have no comment on an ongoing federal investigation,” Viola said, voice carrying clearly in the open air. “But let me be crystal clear about one thing: a courtroom is not a playground for bullies. Threatening a child because you think you’re losing is not advocacy—it’s desperation.”

The crowd quieted in patches, hungry for more.

Viola’s gaze swept the cameras like she was scanning a room for threats. “If you think your wealth makes you untouchable,” she continued, “understand this: the law doesn’t care who you are. And neither do we.”

She guided Jazz down the steps toward a black government SUV parked at the curb, the kind with tinted windows and a presence that said federal without having to say it out loud.

Jazz climbed into the passenger seat and exhaled shakily.

Through the glass, she watched Sterling Thorne appear.

He was being escorted out a side entrance, still shouting, still trying to find a foothold in a world that was refusing to give him one. His suit was wrinkled. His face shone with sweat. His eyes were frantic.

He looked… human.

Not in a sympathetic way.

In a pathetic way.

One of the reporters yelled, “Sterling! Do you still think you’re untouchable?”

Thorne’s head whipped toward the voice. “Do you know who I am?” he snapped, voice cracking.

Someone laughed. Not cruelly. Just incredulously. Like the question itself was a relic.

He was shoved into the back of a cruiser, and the door slammed shut with a finality that sounded like the end of a chapter.

The clip went viral before the cruiser pulled away. By the time Viola drove out of downtown Atlanta traffic and into their neighborhood streets, phones were buzzing with notifications. People were sharing it, commenting, arguing, turning it into content.

Jazz stared out the window and felt something settle in her chest.

It wasn’t satisfaction.

It was resolve.

At home, Viola finally let herself exhale fully. She placed her keys in the bowl by the door. She loosened her jacket. She walked into the kitchen like she needed something normal to ground her.

Jazz followed, still carrying the notebook that had started everything.

Viola poured water into two glasses and slid one across the counter.

Jazz took it and drank like she’d been thirsty for hours.

“You did good,” Viola said quietly.

Jazz blinked. “I didn’t do anything,” she replied automatically.

Viola’s eyes sharpened. “You stood,” she corrected. “You used your voice. You refused to let someone rewrite who you were.”

Jazz looked down at her hands. They weren’t shaking anymore.

“I was scared,” she admitted.

“Of course you were,” Viola said, like fear was not a flaw but a reality. “Courage isn’t the absence of fear. It’s what you do while you’re feeling it.”

Jazz’s throat tightened again, but this time it wasn’t panic. It was emotion rising from somewhere deeper.

“He called me—” Jazz started, then stopped.

Viola didn’t press. She didn’t need the words. She’d heard enough in the courtroom.

Instead, Viola reached across the counter and covered Jazz’s hand with her own. Warm. Solid. Real.

“He saw what he wanted to see,” Viola said. “A target. That’s all. It was never about who you are. It was about what he needed.”

“What did he need?” Jazz asked, voice small.

Viola’s gaze drifted somewhere beyond the kitchen wall, as if she could still see the courtroom. “Control,” she said. “A distraction. A performance. Men like him don’t just want to win. They want to crush. They want the room to agree with their version of reality.”

Jazz swallowed. “But it didn’t,” she said.

Viola’s mouth lifted. “No,” she replied. “It didn’t.”

That night, Jazz slept with her notebook on her desk like a talisman. She didn’t wake to a nightmare, but she did wake early, heart racing, because her brain was still replaying Thorne’s face, his finger inches from her, the way the room had gone silent.

For the first time, she understood something about trauma that adults tried to explain in soft voices: it wasn’t just the event. It was the helplessness.

And now that helplessness had been broken.

The next morning, the world had moved on to the next outrage, the next trending clip, the next scandal. But Jazz’s life didn’t move on that fast. She went to school and sat through math class like she wasn’t carrying a courthouse inside her chest. Friends asked, “Are you okay?” in that teenage way that meant, I don’t know how to hold your pain, but I don’t want you alone.

Jazz told them she was fine. And she was—mostly.

But the hallway lights felt too bright. Loud voices made her flinch. When teachers called on her unexpectedly, her heart spiked like she was back in the gallery.

Viola noticed. Of course she noticed. Mothers notice everything their children try to hide.

That Friday, Viola came home earlier than usual.

“Put your shoes on,” she said.

Jazz looked up from her homework. “Why?”

“We’re going out,” Viola replied. “No arguments.”

Jazz blinked. “Where?”

Viola’s mouth twitched. “Ice cream,” she said.

Jazz almost laughed. “Mom, I’m not five.”

Viola shrugged. “The world was loud,” she said. “We’re going somewhere quiet that tastes sweet.”

They sat in a small shop in a strip mall, the kind with sticky tables and hand-written flavors on a chalkboard. Nobody there cared about a viral clip. Nobody there cared about Thorne. A teenager scooped mint chocolate chip into a paper cup and slid it across the counter like life could still be normal.

Jazz took a bite and felt her shoulders drop.

Viola watched her carefully, then said, “Pendleton called.”

Jazz swallowed. “The ethics guy?”

“Mm-hmm,” Viola replied. “They set the hearing date for disbarment.”

Jazz’s stomach tightened. “So I have to testify,” she said, not a question.

“It’s your choice,” Viola reminded her. “Always.”

Jazz stared at the melting ice cream. The memory of Thorne’s voice tried to rise.

You don’t belong here.

Jazz lifted her gaze. “I’ll do it,” she said again, firmer.

Viola nodded once. “I figured,” she said. “But I wanted you to hear it out loud anyway. Your choice.”

The hearing came quickly.

It wasn’t as flashy as the criminal arrest. No jury. No dramatic doors. Just a panel of attorneys in sober suits and tired eyes, the kind of people who knew the rules intimately and still sometimes watched them get twisted.

Sterling Thorne appeared on a screen via video from federal custody, his face paler, his eyes harsher. He tried to posture. Tried to perform. But it didn’t land the same when you were wearing jail orange behind a camera.

Jazz testified calmly. She told the truth with the kind of precision that made it impossible to spin. She described his accusation, his intimidation, his attempt to seize her phone, his threat to have her jailed.

When she finished, one panel member—an older woman with silver hair and a voice that had probably silenced a thousand meetings—leaned forward and asked, “Miss Reynolds, why did you come to court that day?”

Jazz didn’t hesitate. “To learn,” she said.

The woman nodded slowly. “And what did you learn?”

Jazz’s hand tightened on the edge of the table. Then she said, “I learned some people use the law like a costume. But I also learned some people wear it like a promise.”

The panel’s decision was unanimous.

Disbarred.

No appeal.

No quiet return.

Thorne’s license was stripped like a badge ripped off a liar. The notice went out to every state bar he was admitted to. His name became something law students whispered about like a ghost story: the man who thought he owned the courtroom until a federal star walked in and reminded him he didn’t.

The criminal case did not move as quickly as the internet wanted.

Justice in America is rarely fast. It moves like a heavy machine—slow, grinding, expensive. Months passed. Evidence was processed. Witnesses were protected. Deals were offered. Deals were rejected. Deals were made.

Preston Vain’s defense team tried to build distance between him and Thorne. They painted him as a victim of legal malpractice. They said he didn’t know. They said he was misled. They said he was shocked.

The government responded with receipts.

Emails. Transfers. Encrypted messages. A web of money that didn’t look like confusion—it looked like a plan.

And always, sitting behind the government table, was Viola Reynolds. A quiet reminder that some plans ended in handcuffs.

Sterling Thorne—who had insisted on representing himself out of pride—entered federal court for trial looking gaunt and furious. Jail had stripped away his polish and left only the raw bone of who he was.

Jazz sat in the front row beside her mother, not because she loved the attention, but because she refused to be hidden.

On the day she testified in federal court, she wore the same navy blazer she’d worn on the first day in Courtroom 4B—cleaned, pressed, but now it felt like armor instead of a costume. She climbed into the witness box and looked directly at Thorne.

He tried to smile at her.

It was the old smile—the one that used to make people feel small. But it didn’t fit him anymore. It looked desperate, like a mask held to a face that had already been revealed.

Jazz answered every question carefully. She didn’t exaggerate. She didn’t dramatize. She didn’t give him openings. She gave the truth.

When the prosecutor asked her how she felt that day, Jazz paused.

The courtroom held its breath, waiting for a victim’s voice to break.

Jazz didn’t break.

“I felt like he wanted to erase me,” she said softly. “Like I wasn’t a person in that room. Just a problem.”

Then she lifted her chin and added, “But I also felt something else. I felt that I was watching how power behaves when it thinks nobody’s going to stop it.”

The judge’s eyes stayed on her, steady and serious.

Thorne’s face reddened.

And then Jazz said the sentence that landed like a quiet bomb in that federal courtroom:

“I decided I didn’t want to spend my life being afraid of people like him. I want to spend my life stopping them.”

After her testimony, as she stepped down from the witness box, Viola caught her arm gently.

“You did it,” Viola whispered.

Jazz nodded, chest tight. “I did,” she replied.

Thorne’s trial ended the way so many spectacular collapses ended.

Not with a dramatic speech.

With a verdict read in a steady voice.

Guilty.

Again and again.

The jury didn’t take long. They didn’t need to. The evidence was thick. The pattern was clear. The arrogance that had protected him had also exposed him. Thorne had lived for performance, and performance had left fingerprints everywhere.

When Judge Wright sentenced him, the courtroom did not gasp the way it does in movies. People didn’t clap. They didn’t cheer. This wasn’t entertainment.

It was reckoning.

Thorne begged. He tried to bargain. He tried to turn his suffering into sympathy. But the judge had heard every trick.

“You used the law as a weapon,” Judge Wright said coldly. “And when you couldn’t control the room, you went after a child.”

Thorne’s eyes flicked toward Jazz in the gallery like he wanted to blame her. Like he wanted to rewrite the story one last time.

But Jazz didn’t look away.

She held his gaze without hatred. Without triumph. Just with the steadiness of someone who had learned, too early, what power looked like.

Judge Wright finished with words that felt like a door closing:

“You will never practice law again. You will never stand in a courtroom again unless you are in chains.”

The marshals moved in.

The cuffs clicked.

Thorne tried to pull away, to run, to resist the reality of his own downfall. He stumbled. He fell. He was hauled up like a man who weighed nothing more than his own bad choices.

As he was dragged out, his voice cracked into something almost childlike.

“This isn’t fair,” he cried.

And from somewhere in the gallery, someone whispered, not loud enough to be a disruption, just loud enough to be true:

“Neither was what you did.”

Outside the courthouse that day, the media waited again, hungry to turn an ending into a headline. But Jazz didn’t want the cameras. She didn’t want the questions. She didn’t want to become content.

Viola guided her away, as she always had.

They walked to the same small park two blocks away and sat on the same bench. The sky was bright. The city moved. The world kept going.

Jazz stared at her hands.

Viola watched her carefully. “You okay?” she asked.

Jazz swallowed. “I think I am,” she said.

Then, quietly: “It’s weird. I thought I’d feel… happier.”

Viola nodded like she understood. “Justice doesn’t always feel like fireworks,” she said. “Sometimes it feels like exhaling after holding your breath too long.”

Jazz let the words settle. “I keep thinking about how easily he did it,” she admitted. “How easily he decided I didn’t belong.”

Viola’s eyes hardened. “That’s why you’re going to do what you said you’re going to do,” she replied. “You’re going to become the kind of lawyer who makes it harder for men like him to use the system as a hunting ground.”

Jazz’s throat tightened. “I want that,” she whispered.

Viola reached into her pocket and pulled out a folded piece of paper.

Jazz blinked. “What’s that?”

Viola’s mouth softened. “It came today,” she said.

Jazz stared. “From where?”

Viola turned it so Jazz could see the return address printed in formal blue type.

Yale University.

Jazz’s breath caught so hard it felt like her lungs forgot their job.

Viola slid the envelope into her hands like she was handing her a future.

Jazz didn’t open it right away. She just stared at it, afraid that if she moved too fast, the moment would break.

“Open it,” Viola murmured.

Jazz’s fingers trembled. She tore the seal and unfolded the thick letter inside. Her eyes moved across the words, and then they stopped because her brain couldn’t process them at first.

It is with great pleasure…

Jazz’s mouth opened. No sound came out.

Viola leaned closer, eyes shining.

Jazz read it again. Slower. Just to make sure.

Admission.

Class of 2029.

She looked up at her mother, and the emotion hit her like a wave that had been waiting behind a dam.

“I got in,” she whispered.

Viola’s face crumpled into a smile that was pure, fierce, exhausted love. She pulled Jazz into her arms so tightly Jazz felt her own heartbeat echo against her mother’s chest.

“My baby,” Viola whispered, voice breaking. “My baby.”

Jazz laughed and sobbed at the same time, the sound half joy, half relief. “I wrote my essay about the courtroom,” she admitted, face pressed into Viola’s shoulder. “About what it felt like. About what I want to do.”

Viola pulled back and held Jazz’s face, thumbs brushing away tears.

“You’re going to be the one who changes it,” Viola said. “You’re going to be the one who makes sure the back row matters.”

Jazz nodded, tears still falling. “I want to fight for people who don’t get believed,” she said. “People who get pointed at and labeled before they even open their mouth.”

Viola’s gaze locked on hers, steady as steel.

“Then you will,” she said. “And you’ll do it the right way.”

Years moved forward the way they always do—fast when you look back, slow when you’re in them.

Jazz left for college with suitcases and a scholarship packet and a mother who watched her walk through the dorm doors like she was watching a miracle she had built with her own hands. Viola didn’t cry until Jazz was out of sight. Then she sat in her car for a long time with her hands on the steering wheel, breathing through the ache and the pride.

Jazz worked like someone who had seen what happened when people didn’t. She studied late, not because she liked suffering, but because she knew what was on the other side of ignorance. She interned. She volunteered. She sat in legal clinics listening to people whose lives had been chewed up by systems that treated them like paperwork.

And sometimes, on nights when the campus was quiet and the library lights made everything feel sterile and far away, Jazz would remember the heat of Courtroom 4B and the sound of the doors slamming open like thunder.

She’d remember her mother’s voice: You okay, Jasmine?

And she’d keep going.

Viola retired from the Marshals Service after enough years of doing hard work in hard places. She didn’t retire into softness. She retired into presence. She became the mother who always answered the phone. The woman who showed up to every graduation, every internship celebration, every moment that mattered.

When Jazz got into Yale Law, Viola didn’t tell anyone at first. She sat at her kitchen table with the acceptance letter in her hands and let herself feel it privately—like a prayer answered.

When Jazz graduated near the top of her class, Viola sat in the front row with her hands clasped and her chin lifted, looking like she was daring the universe to deny her child.

And when Jazz applied for internships and clerkships and her name started to appear in rooms that used to ignore people like her, Viola stayed steady.

“Remember,” she told Jazz on the phone one night, “power is not how loud you are. It’s how consistent you are.”

Jazz never forgot.

Sterling Thorne served most of his sentence. The world outside moved on. His name faded from headlines into legal databases and cautionary lectures. In prison, he wasn’t “Sterling Thorne, defense powerhouse.” He was just another man in a uniform that didn’t care about his résumé.

He wrote letters sometimes—complaints, appeals, self-pity disguised as philosophy. Nobody answered. His former partners didn’t visit. His former clients didn’t remember him. The machine he had fed for decades didn’t mourn him.

He died not in a blaze of tragedy but in the flat anonymity he’d always reserved for other people.

And the city barely noticed.

Jazz noticed, though—not because she mourned him, but because she understood the symbolism. A man who had treated the law like a personal weapon ended exactly where the law placed him.

Not special.

Not spared.

Just held.

Ten years after Courtroom 4B, Jazz stood in a different courtroom on a different morning, wearing a tailored suit that fit her like a decision.

She wasn’t in the back row.

She was at the prosecution table.

Her briefcase was heavy with files and names and lives. She set it down carefully, feeling the polished wood beneath her palm. It was the same courthouse—Fulton County. The same building that had once held her fear.

But the air conditioning worked now. The air moved cool and clean across the room like the building itself had learned something.

Jazz lifted her gaze to the bench and breathed.

“All rise,” the bailiff called.

Jazz stood.

In the back row of the gallery, one woman sat quietly, hands folded, hair silvered at the edges, posture still straight as a badge.

Viola Reynolds.

Retired U.S. Marshal.

Still a mother first.

Jazz’s eyes met hers. They held for a heartbeat.

Viola smiled the way she always did when Jazz stepped into the world: proud, calm, unshakably present.

Jazz turned back to the front. The judge entered. The room settled.

A case was called.

A defendant stood.

A victim waited.

The law began to move the way it was supposed to move—toward truth, toward accountability, toward the kind of justice that didn’t depend on who was rich or loud or connected.

Jazz stepped forward when it was her turn to speak. Her voice carried cleanly through the courtroom. Not because it was loud, but because it was certain.

She felt the weight of her role and the weight of her history and the weight of everyone who had ever sat in the back row praying not to be seen as a threat.

She spoke anyway.

And somewhere deep inside her, in the place where fear used to live, there was something else now.

A steady, quiet power.

Not borrowed.

Earned.

After court recessed, Jazz walked down the aisle toward the gallery. She stopped at the back row, just for a moment, and looked at the bench where she’d once been pressed into a wooden seat by intimidation.

She could almost hear it again—Thorne’s voice, his accusation, his belief that he could decide who belonged.

Jazz turned to her mother and smiled.

Viola reached up and squeezed her hand.

“You did it,” Viola whispered.

Jazz shook her head gently, eyes shining. “We did,” she corrected.

They walked out of the courthouse together into a bright afternoon where the city didn’t pause for anyone, where people hurried past with coffee and phones and lives.

And yet, something had changed—something you couldn’t always measure on paper.

Because sometimes justice isn’t a dramatic speech.

Sometimes it’s a door opening for someone who used to be told to stay out.

Sometimes it’s a girl who was once accused for existing in the wrong place, now standing at the center of that place, making sure nobody else gets treated like prey.

And sometimes, the most American thing you can do isn’t to be loud.

It’s to be unmovable.

To show up.

To learn.

To tell the truth.

To become the kind of power that bullies fear—not because you’re cruel, but because you refuse to bend.

Jazz had come to court that first day to log hours for a class.

She walked out with a lifetime assignment.

And she never put it down.

News

PACK YOUR THINGS. YOUR BROTHER AND HIS WIFE ARE MOVING IN TOMORROW,” MOM ANNOUNCED AT MY OWN FRONT DOOR. I STARED. “INTO THE HOUSE I’VE OWNED FOR 10 YEARS?” DAD LAUGHED. “YOU DON’T ‘OWN’ THE FAMILY HOME.” I PULLED OUT MY PHONE AND CALLED MY LAWYER. WHEN HE ARRIVED WITH THE SHERIFF 20 MINUTES LATER… THEY WENT SILENT.

The first thing I saw was the orange U-Haul idling at my curb like it already belonged there, exhaust fogging…

I was at airport security, belt in my hands, boarding pass on the tray. Then an airport officer stepped up: “Ma’am, come with us.” He showed me a report—my name, serious accusations. My greedy parents had filed it… just to make me miss my flight. Because that morning was the probate hearing: Grandpa’s will-my inheritance. I stayed calm and said only: “Pull the emergency call log. Right now.” The officer checked his screen, paused, and his tone changed — but as soon AS HE READ THE CALLER’S NAME…

The plane dropped through a layer of gray cloud and the world outside my window sharpened into hard lines—runway lights,…

MY CIA FATHER CALLED AT 3 AM. “ARE YOU HOME?” “YES, SLEEPING. WHAT’S WRONG?” “LOCK EVERY DOOR. TURN OFF ALL LIGHTS. TAKE YOUR SON TO THE GUEST ROOM. NOW.” “YOU’RE SCARING ME -” “DO IT! DON’T LET YOUR WIFE KNOW ANYTHING!” I GRABBED MY SON AND RAN DOWNSTAIRS. THROUGH THE GUEST ROOM WINDOW, I SAW SOMETHING HORRIFYING…

The first thing I saw was the reflection of my own face in the guest-room window—pale, unshaven, eyes wide—floating over…

I came home and my KEY wouldn’t turn. New LOCKS. My things still inside. My sister stood there with a COURT ORDER, smiling. She said: “You can’t come in. Not anymore.” I didn’t scream. I called my lawyer and showed up in COURT. When the judge asked for “proof,” I hit PLAY on her VOICEMAIL. HER WORDS TURNED ON HER.

The lock was so new it looked like it still remembered the hardware store. When my key wouldn’t turn, my…

At my oath ceremony, my father announced, “Time for the truth-we adopted you for the tax break. You were never part of this family.” My sister smiled. My mother stayed silent. I didn’t cry. I stood up, smiled, and said that actually I… My parents went pale.

The oath was barely over when my father grabbed the microphone—and turned my entire childhood into a punchline. We were…

DECIDED TO SURPRISE MY HUSBAND DURING HIS FISHING TRIP. BUT WHEN I ARRIVED, HE AND HIS GROUP OF FRIENDS WERE PARTYING WITH THEIR MISTRESSES IN AN ABANDONED CABIN. I TOOK ACTION SECRETLY… NOT ONLY SURPRISING THEM BUT ALSO SHOCKING THEIR WIVES.

The cabin window was so cold it burned my forehead—like Michigan itself had decided to brand me with the truth….

End of content

No more pages to load