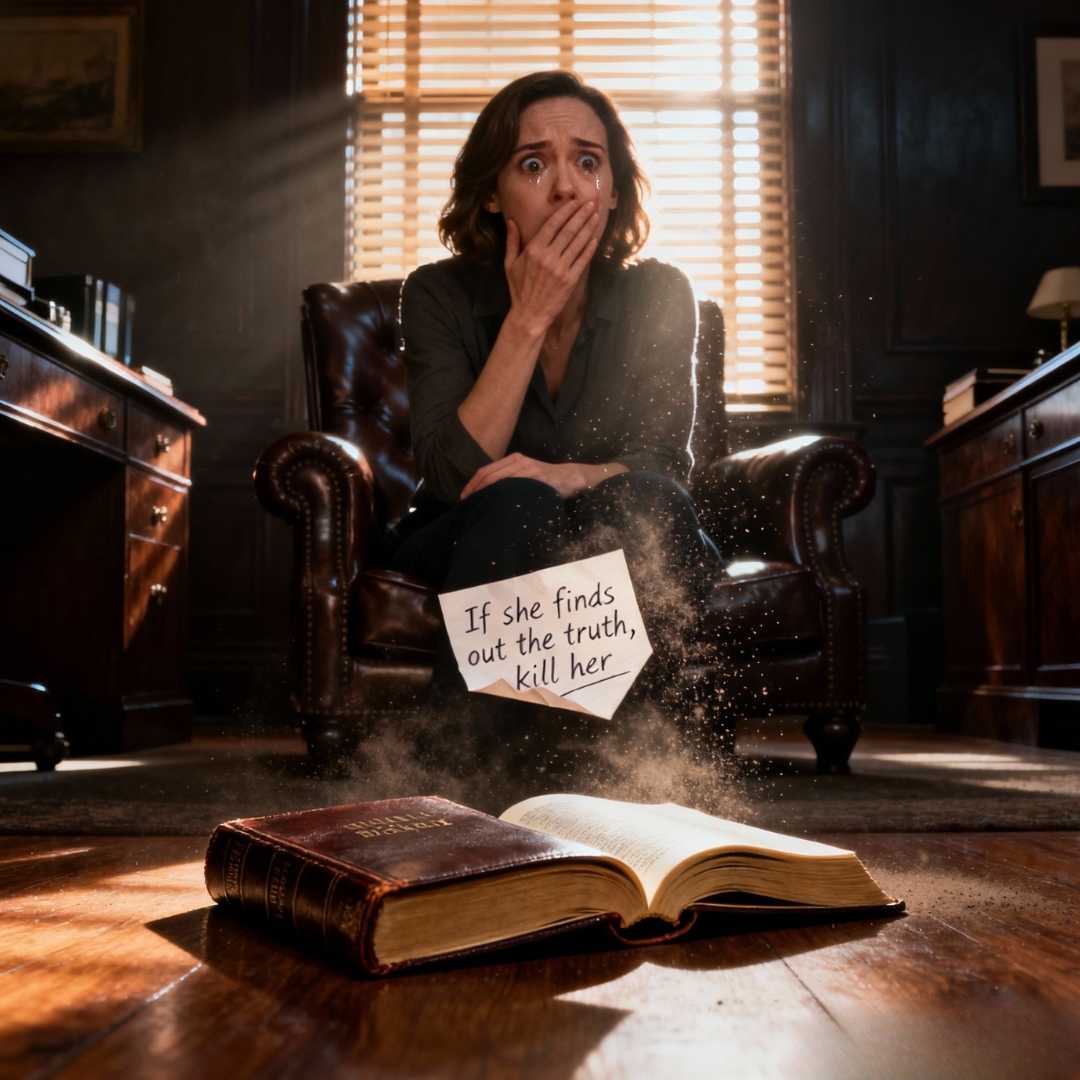

The Bible didn’t fall; it crashed to the floor like a thunderclap in the middle of my quiet Virginia afternoon, the old leather cover flinging open as if pushed by an invisible hand. A piece of paper, small and pale as a moth’s wing, slipped from between its yellowed pages and fluttered down in slow motion. I watched it spin through the still air of my husband’s office, turning once, twice, three times, before landing at my feet.

My first thought was ridiculous and simple: Anthony is going to be so angry that I touched his Bible.

Then I bent down, picked up the paper, unfolded it with fingers trembling from a migraine and something deeper I couldn’t name, and read seven rushed, slanted words that froze my blood in my veins.

If she discovers the truth, kill her.

The pain in my head vanished. My vision narrowed to a bright, ringing tunnel. The hum of the refrigerator in the kitchen went silent, the distant drone of a passing airplane faded, even the cicadas outside our house on Willow Creek Road seemed to fall mute. All that existed were those seven words, pressed into cheap white paper by a hand I recognized instantly.

The handwriting belonged to Edward.

Edward Harrison: manager of the First National Bank of Willow Creek, the man my husband worked under every day. He sent Christmas cards to our home in the Commonwealth of Virginia each year, carefully scripted greetings with wishes for “peace and prosperity” written in that same slightly slanted style. He shook my hand politely at church, asked after the children, tipped his hat in that old-fashioned American gentleman way when he passed me on Main Street.

And he had written a line instructing someone to kill her.

Who was she?

I didn’t have to ask very hard before the answer rose like bile in my throat.

Me.

The Bible lay at my feet, sprawled open on the carpet, pages bent and fragile, open somewhere in Proverbs where Anthony always claimed wisdom lived. The note must have been hidden there—between verses about faithfulness and integrity, tucked into an American family heirloom that had traveled from a dusty farmhouse in Pennsylvania to our small brick-and-wood home in Virginia.

I stared at the words again, just to be sure I wasn’t hallucinating from the migraine.

If she discovers the truth, kill her.

There was no misunderstanding that. No room for “maybe it means something else.” In a country where the nightly news showed protests against the Vietnam War, campus uprisings, marches for civil rights, where the television anchors spoke every evening about life and death and truth and lies across the United States, I was suddenly living my own private, terrifying little headline.

“LOCAL BANKER PLOTS TO SILENCE WIFE,” I imagined in bold black letters on the front of The Washington Post.

I felt dizzy, but not from pain this time. My heart galloped wildly, then slammed into a strange, cold rhythm. A quiet voice whispered in my head: Put it back. Put it back, Gertrude, and pretend you never saw it. Pretend it’s nothing. Pretend you are still safe.

But I was not safe.

I carefully folded the note back along the existing creases, my fingers stiff as wood. I tucked it exactly where I had seen it fall from, between two thin pages of the Bible, smoothing them gently as if I were restoring the dead to rest. I closed the book and placed it back on the shelf in Anthony’s office, the spine lined up perfectly with the other volumes he liked to display but never read.

I knew where everything belonged in that room even though I was never supposed to be in it.

“A man needs a space where he can think,” Anthony always said, shutting the door behind him every evening.

Until that day, I had obeyed. American wives were good at that back then—especially in small towns like ours, where the most exciting thing that happened in a week was a new pie recipe at the church potluck or a rumor that someone’s cousin from D.C. had come to visit.

I wasn’t supposed to be there at all.

It was my mother’s birthday that Sunday—August 17, 1969. The date would burn itself into my memory like a brand. The children were at my mother-in-law’s house for lunch. Anthony had left earlier claiming he needed to go to the bank to prepare for a “big transfer” coming from the textile company the following week. My head had been pounding all night, a brutal migraine that made the morning sun slanting over the American flag across the street feel like a spotlight.

I knew Anthony kept strong pain medication in his office drawer, pills he’d brought back from a trip to New York City and told me were “too strong” for me to use without his supervision. That afternoon, the pain didn’t care about his rules. I stepped over that invisible line and opened his desk drawer.

I found the pills.

And then I bumped the bookshelf.

And the Bible came crashing down.

I took the medication, washed it down with cool tap water from our kitchen sink, and then lay down on the couch in the living room. I closed my eyes, one hand pressed over my fluttering heart, and tried to breathe.

When Anthony came home later, with his calm voice and his neutral eyes and his “How are you feeling, Gertrude?” I was already an actress. I smiled faintly. I spoke softly. I moved slowly. I looked sick and grateful for his concern.

Inside, I was a fault line ready to split the ground beneath us.

My name is Gertrude Miller, and on that day in 1969, I stopped being simply a wife in a quiet American town and became something else entirely.

I became a woman who knew her life was in danger.

I became a woman who knew her husband had secrets big enough to kill for.

And I swore, silently, as Anthony kissed our daughter’s forehead and ruffled our son’s hair before dinner, that no one—not my husband, not his boss, not any man in a suit with a polite handshake and an expensive tie—was going to decide if I lived or died.

They wanted me silent.

Instead, I started to watch.

For the next days, life in our house went on exactly as before—at least on the surface. The United States spun on. Walter Cronkite still read the nightly news. Headlines still shouted about troop withdrawals and protests and the moon landing. Cars still drove past our tree-lined street, honking sometimes as they rushed toward Richmond or D.C. Our neighbors still waved from their porches and mowed their lawns like any typical American Sunday.

But inside the walls of our home, everything had changed.

I woke up every morning before dawn like always, prepared breakfast like always, ironed shirts and scrubbed floors and sewed dresses for town ladies who liked to comment on the latest news from Washington as if that world and ours were the same.

I packed lunches. I tied shoelaces. I kissed scraped knees.

And I observed.

I watched Anthony slip keys into his pocket.

I watched how carefully he locked his desk drawer now. I watched how he flinched when the phone rang after dinner, sometimes picking it up and lowering his voice, sometimes ignoring it and letting the rotary phone spin itself uselessly on the table. I noticed how the first Thursday of each month—the day of his “business trips”—seemed to hang heavier in the air.

I might have convinced myself, for a while, that I was exaggerating. That maybe the note was a twisted joke or a misunderstood fragment torn from some larger, less sinister sentence. But a week after the Bible incident, reality decided to slap me across the face.

I was ironing his navy suit, the one he wore for important meetings and funerals, humming along with a Motown song on the small kitchen radio, when I slipped my hand into the inner pocket to smooth the lining.

My fingertips brushed thin, crumpled paper.

I pulled it out.

A receipt from a jewelry store in Richmond. The amount almost made me drop the iron.

My husband gave me enough money for groceries, a little extra for the children’s shoes if I budgeted carefully. I knew every cent that went in and out of that house. That receipt held a number that belonged in someone else’s life entirely—wealthy ladies in New York, politicians’ wives in D.C., Hollywood stars in California. Yet there it was, connected to my husband, to our small Virginia town, printed neatly with the words:

One solitaire diamond engagement ring.

He had never given me an engagement ring.

Our wedding band exchange had been simple, quiet, modest—a gold band on my finger in a little church with white wooden pews and a choir humming softly in the background. I still wore that ring as I held the receipt, my left hand trembling so hard the paper rattled.

In the same pocket, folded more carelessly, I found a small card with an address scribbled on it. An address in Richmond. My stomach clenched. I didn’t know that block or that street, but I knew enough.

I put everything back.

Exactly where I had found it.

That night, I served dinner, laughed at the appropriate moments during Anthony’s stories, nodded when he complained about a stubborn client, kissed him lightly on the cheek when he leaned over my shoulder to see what dessert I was making.

Inside, I had moved from suspicion to certainty.

Anthony was living a second life.

And somewhere out there, in the same state, under the same American flag, a woman who wore a solitaire diamond on her finger was planning a future with my husband.

On my third trip to Richmond under the excuse of buying special fabric and visiting a cousin, I found her house.

It stood in a clean, quiet neighborhood with neat lawns and white fences, not far from a school where children’s laughter drifted across the afternoon like birdsong. While I stood on the sidewalk pretending to adjust my purse strap, a woman watering her front yard looked up and smiled the way strangers in America often do when they assume you are just passing through.

“You lost, honey?” she called.

“Just looking for an address,” I replied, giving her the number written on the card.

She pointed next door. “That one. The teacher’s house. Sweet girl. Maryanne. Expecting, poor thing. Her fiancé comes every Thursday when he can get away from his job out of town. They say he’s trying to finish things up with his ex-wife so they can get married.”

I couldn’t hear anything else after that.

First Thursday.

Ex-wife.

Expecting.

I felt as if I had been plunged into icy water. The pieces slammed together so quickly it almost hurt.

That was why he always traveled on the first Thursday.

That was why he’d become more distant, colder, more dismissive.

That was why he had an engagement ring receipt in his pocket.

He wasn’t just planning to leave me.

He had already left me somewhere in his heart and mind. I was the leftover chapter in a story he had rewritten without telling me.

Back in our town, as the American flag flapped gently over the post office and children rode their bikes past the bank where Anthony smiled at customers from behind his desk, I moved with a new kind of clarity.

If I confronted him now, if I screamed or begged or demanded answers, that note from the Bible would shift from threat to plan.

If she discovers the truth, kill her.

I couldn’t risk it.

So instead, I dug deeper.

I befriended the new bank secretary, a widow named Irasema, chatting after Sunday mass and at the grocery store, trading recipes and gossip like any other women. She was kind, lonely, eager for connection.

“We’re all exhausted at the bank,” she said one morning, leaning toward me between rows of canned soup and baking flour. “There’s a huge transfer coming at the end of the month. Federal money from Washington for the textile plant. They say it will expand jobs for the whole county. Your husband and Edward were working late again last night. I’ve never seen so many zeros on a document in my life.”

Half a million dollars.

In 1969, that wasn’t just money. That was a fortune. That was new houses, new factories, new cars parked in driveways, college funds, and retirement accounts before most people even had those words in their vocabulary.

That was also motive.

I remembered the key I’d found months earlier in Anthony’s shaving kit, the one he had snapped out of my hand with a curt, “That’s just an old file cabinet key at the bank, Gertrude. Don’t touch my things.”

Now, it hummed in my memory like an alarm.

I waited until he left for work and the children rode off to school. Then I searched. I went through drawers, the backs of closets, the bottom of boxes labeled “OLD TAXES” and “MISC.” My heart pounded against my ribs, but my hands were steady.

I found the key where he thought I would never look: inside a fake book on the shelf, a hollowed-out volume on business ethics. I could almost hear God laughing, grim and tired.

The key fit a small metal lockbox tucked behind our suitcases. Inside, laid out with the precision of a man who loved numbers, were:

Two ship tickets to Argentina, in the names of Anthony Miller and Maryanne Oliveira.

Fake identification cards with their faces staring up at me under different names.

Receipts. Notes. A rush of love letters from Maryanne, pages smelling faintly of perfume, talking about “our new life,” “our baby’s room,” “getting away from that small town,” “finally being free.”

At the very bottom was a letter that made my hands go numb.

My love,

only two weeks now until we are together forever. The baby’s crib is ready. I can’t wait to start our real life far from that suffocating place and that woman who never deserved you. Be careful with the last details. As Edward says, if she finds out before the time, you know what needs to be done. But everything will work out. Soon we’ll be the family we dreamed of.

With all my love,

Maryanne.

I read it once.

Twice.

A third time.

I saw my entire life—ten years of marriage, two children born on American soil, countless dinners served hot, nights awake with fevers and nightmares, holidays, birthdays, anniversaries—shrunk down to a single dismissive line.

“That woman who never deserved you.”

I sat on the floor of my bedroom, the metal box open beside me, the evidence of betrayal and crime spread out like a map of the worst parts of the human heart, and I made a decision that lit up every cell of my body.

I would not die for this man’s freedom.

I would not be erased so he could reinvent himself overseas.

I would not let my children wake up motherless someday while Anthony stood on a sunny street in Buenos Aires, carrying a new baby and pretending he had never had a wife in Virginia.

They had plans.

Now I had one too.

I put everything back.

The key returned to its hiding place.

The letters, tickets, and documents went back into the metal box, the metal box back behind the suitcases. When I closed the door to the closet, you would never have known that inside that space lay evidence that could send two well-respected American bankers to prison.

I knew what I needed: money, proof, a protector, and a future.

Money first. I couldn’t depend on my husband’s salary or the “household allowance” he tossed at me like a favor. My secret sewing income, the little stash I’d been tucking away for years inside the hem of a winter coat, suddenly became sacred. I went to Richmond with one of my most generous clients, a wealthy widow named Eulalia, who marched me straight into a bank and introduced me to the manager with the kind of confidence only an older American woman with money can display.

“This is Mrs. Miller,” she said. “She needs her own account. Don’t bring her husband into it. It’s her money, and she’ll do with it what she pleases.”

I deposited every saved dollar. It wasn’t much. It was everything.

Proof came next.

The Kodak camera fit in my hand like it had been waiting for this moment. Tiny. Quiet. Easy to hide in a sewing basket or under a scarf. I started slipping into Anthony’s office when he left early, moving like a ghost, pulling out files, snapping quick photos of forms and statements, simmering in a mix of fear and furious purpose. Names of fake accounts. Tiny withdrawn sums diverted over years. The pattern of fraud building up like layers of sediment on a riverbed.

I needed copies of official documents too, ones beyond question.

The only copy machine in town belonged to the stationery store, behind the shelf where schoolchildren bought their notebooks and pencils. The owner—Mr. Moses—was a kind man with two boys who played baseball with my son and a wife who often wore the dresses I sewed.

“You know it’s not for public use, Mrs. Miller,” he said, scratching his head when I asked to use it one afternoon.

I leaned into every bit of charm and helplessness I could summon. “It’s for a surprise for my husband. Copies of our children’s birth certificates, our marriage certificate… I want to make an album for his birthday.” I gave him a smile. “I’ll fix your wife’s dress hem for free.”

He sighed. “Well, I suppose for a few documents, just this once.”

In less than an hour, I walked out of that shop with copies of the most incriminating pieces of Anthony and Edward’s scheme tucked under my blouse, pressed against my racing heart. I felt like a spy. Like the heroines in those American movies I’d only half-watched on television with the sound down.

Then I needed a protector.

That meant I needed someone who worked above the local sheriff who played cards with my husband on Saturdays, above the judge who had baptized my son, above the priest who heard Edward’s quiet confessions in his office after mass.

I needed someone from outside our town. From the capital. Someone with a badge that couldn’t be influenced by a neighborly handshake.

Inspector Mendes.

I had heard his name whispered with a mix of respect and annoyance for years. He came from Washington periodically to inspect the bank, a federal man in a sharp suit with eyes like a hawk and a reputation for rejecting bribes. Anthony hated him.

“He thinks he’s some kind of hero, coming down from D.C. like this is a movie,” he’d grumble, loosening his tie after one of those visits. “He doesn’t understand that small towns work on trust.”

From what I had learned lately, trust in our small town had become a weapon.

So I chose the man who was immune.

I learned from Irasema that he was staying at the Cedar Grove Inn next week. I couldn’t walk in there and hand him the documents; too many eyes in our town. But my daughter, Teresa, had a friend whose parents owned the inn. They often played together after school.

I invited Teresa and her friend for an afternoon snack there, praising the inn’s homemade lemonade. While the girls played near the front desk, I complimented the owner’s purse—beautiful, leather, just the right size.

“Would you mind if I borrow it for a day?” I asked sweetly. “I’m sewing a dress and need to check measurements for a matching handbag.”

She laughed and handed it over.

At home, I slid the envelope of copies into the lining of the purse, stitched it closed with such invisible precision that no one could have guessed anything was hidden there. I added a short note: “For Inspector Mendes. Please deliver discreetly. Lives depend on it.”

When I returned the purse, I mentioned casually, “I heard the inspector’s coming next week. Perhaps he’ll stay here again?”

The owner brightened. “He always does when he’s in town. Good man. Polite. Quiet.”

“Please give him this purse as a thank-you from the ladies who appreciate his help keeping our town honest,” I said. “But don’t tell him who it’s from. Some people don’t like the attention.”

There it was.

My entire life’s safety, sewn into the lining of a handbag, entrusted to a stranger’s kindness and a federal inspector’s conscience.

The last thing I needed was a future.

Louise, my childhood friend who now ran a small sewing studio near Washington, D.C., provided that.

When I called her from our avocado-green rotary phone, my voice shaking, I didn’t tell her everything. Not about the note. Not about the tickets. Not about Argentina.

“My marriage is… ending,” I said simply, my voice barely louder than a breath. “I might have to leave quickly. I’ll need work. The children will need a place to stay, at least for a while.”

Without hesitating, she said, “Come. I have a small room behind the studio. It’s not much, but it’s yours. We’ll make it work.”

That’s the thing about true American friendship: sometimes it’s a woman showing up for another before she even knows the whole story.

The days ticked past toward the transfer like a countdown clock.

Anthony grew more tense. He watched the children more often at dinner with a faraway look, like he was memorizing their faces. He shut his office door a little harder at night. He looked at me sometimes as if he wanted to say something, but never did.

On the eve of the transfer, he gave me more cash than I’d asked for when I mentioned needing money for fabric.

“Buy something for yourself, too,” he said, eyes flicking over my face.

He had never done that. Generosity was not a habit with him. It felt like hush money from a man who thought he would be gone soon enough that my spending wouldn’t matter.

That night, I moved like a ghost between the children’s beds, adjusting Michael’s blanket, brushing Teresa’s curls off her forehead, memorizing the curve of their sleeping faces. Anthony snored lightly beside me when I finally lay down, but there was no sleep in my body at all. Every tick of the bedside alarm clock felt deafening in the quiet Virginia night.

The morning of the transfer dawned bright and clear, as if the sky itself didn’t know what was about to happen.

From our kitchen window, I watched American flags on the street sway gently in the early light. I fried eggs. Buttered toast. Packed lunch boxes. Kissed my children and sent them off. Anthony straightened his tie in the mirror, checked his watch, then turned to us.

“I’ll be late tonight,” he said, avoiding my eyes. “Important work. Don’t wait up.”

He hugged the children too long. He kissed my cheek as if I were already a ghost.

When the front door shut behind him, I stood in the foyer and listened to the silence.

“This is it,” I whispered to no one.

I packed documents and photographs, birth certificates and vaccination records into a small pile. I tucked extra money into my bra, into my shoes, into the hollow of an old pillow. I packed two small bundles of clothes and pushed them under the bed. If I had to run, I could do it within minutes.

In the afternoon, Irasema appeared at my back door, breathless, under the pretense of fitting a dress.

“There are men from the capital at the bank,” she whispered, lips barely moving as I pinned the fabric at her waist. “They arrived in two cars with government plates. The inspector is with them. They’re asking to see everything. Edward looks sick. Your husband tried to leave, but they told him to sit down.”

I nodded as if I were simply calculating seam allowances.

“Sounds like an important day,” I said evenly.

She left. I stacked my sewing neatly. I walked to the window. The town looked the same: kids on bikes, a dog trotting down the sidewalk, the mail truck turning the corner like any other American afternoon.

Yet I knew that inside the bank, something irrevocable was happening.

I took the children to their aunt Lucinda’s house under the pretense of needing a quiet afternoon for work. “Keep them tonight if you can,” I added lightly. “I might sew late.”

The sun had begun to sink when I heard sirens.

They wailed down the road, slicing the air, the kind of sirens that make curtains twitch in every window along the street. Three police vehicles tore past our house toward the town square, red lights flashing across familiar storefronts.

My knees nearly gave out.

Half an hour later, someone pounded on my front door. Hard.

I opened it with shaking hands.

Lucinda stood there, flushed and bewildered.

“Gertrude,” she gasped, “have you heard? They arrested them. They arrested Anthony and Edward at the bank. The inspector had documents, photographs, everything. They’ve been taking money for years. And they found tickets to Argentina. With some woman’s name. Mary… Mary something. They say she’s pregnant. There’s going to be a scandal. The whole town is at the square right now.”

I let myself sway, grabbing the frame of the door like an actress in a soap opera. The shock on my face wasn’t entirely fake, but it wasn’t for the reasons everyone assumed.

It wasn’t because my husband was a criminal.

It was because my plan had worked.

The note in the Bible had not become my death sentence.

It had become my key to freedom.

That week, the First National Bank of Willow Creek closed for a federal audit. Men in suits from Washington moved in and out with briefcases, while townsfolk clustered on sidewalks whispering like we lived in some sensational headline from one of those American scandal papers—secret lives, double betrayals, stolen money.

People looked at me in two ways: with pity, or with curiosity.

“The poor wife,” some said.

“How could she not know?” others whispered.

I refused to hide.

The morning after the news broke in the local paper—“BANK SCANDAL ROCKS SMALL VIRGINIA TOWN”—I put on my best navy dress, pinned my hair in place, brushed a touch of lipstick on my lips, and walked to the market.

Every conversation stopped when I walked in.

Mrs. Zulmira from the inn broke the silence. “Good to see you out, Mrs. Miller. If you need anything, you just let us know.”

“Thank you,” I said calmly, straightening my shoulders. “My children will need milk, and life will go on.”

It did.

Just not in the way anyone expected.

A few days later, I was summoned to the capital to give a statement. The bus ride to Washington, D.C., felt like traveling to another planet. My hands stayed clasped in my lap the entire time, knuckles white, my eyes watching the miles of American countryside fly by.

In a stark room with three men—Inspector Mendes, a prosecutor, and a clerk refining his notes—I told them what they needed to hear.

No more.

No less.

I admitted when I had suspected. I downplayed my own involvement. I let them believe what was safest: that some anonymous, desperate soul had delivered those documents to the inspector because they couldn’t live with the guilt. Mendes’ eyes, dark and sharp, lingered on me longer than the others.

“Whoever sent that envelope,” he said at the end, when the others had stepped out briefly, “saved a lot of people. Including you and your children.”

I held his gaze and said nothing. He handed me a card with a D.C. phone number on it.

“If you ever need anything,” he said, “call me.”

We lost the house.

I expected that. It was financed by the bank, built on the illusion of honest work. The bank reclaimed it as part of the settlement. I explained to the children that their father had done something very wrong and would be away for a long time. I didn’t use words like prison or crime. Not yet. They were eight and six. They didn’t need every detail.

“Does he still love us?” Teresa asked, eyes wide, clutching her doll.

“What happened has nothing to do with his love for you,” I said, because that’s what you say in America when you don’t want to plant bitterness into your children’s hearts too early. “Sometimes adults make choices that hurt everyone. But I am here. And I’m not going anywhere.”

Michael, quieter, older in his mind than his years, looked at me with something like understanding.

“Are you leaving him?” he asked.

“We’re starting over,” I said quietly. “Just you and me and your sister. We’re going to the city. We’re going to build a new life.”

I sold the furniture that belonged to me outright, packed what we could into suitcases, accepted a discreet envelope of cash from Mrs. Eulalia—“A loan,” she insisted, “pay me back when you can”—and boarded a bus with my children for Washington, D.C.

That’s how we left our small Virginia town behind, watching through the window as it shrank into a cluster of memories and scandals and whispers. That’s how I looked at my reflection in the glass—a twenty-nine-year-old American woman with dark hair, tired eyes, two children leaning sleepily against her shoulders—and realized I wasn’t afraid anymore.

For the first time in my life, the fear had burned out and left something cleaner in its place: determination.

Louise met us at the bus station, bustling us into her car with hugs and a smile that told me I didn’t need to explain myself yet.

“Welcome to your new life,” she said as we pulled onto the crowded D.C. streets, headlights smearing light across the windshield like hope.

The room behind her sewing studio was small, with a narrow bed we would share, a wobbly table, a wardrobe that smelled faintly of mothballs. The bathroom was down the hall. The window looked out onto an alley where delivery trucks passed at dawn. It was heaven.

It was ours.

The next months were hard in every way a life can be hard in America—no space, little money, constant exhaustion, the feeling that the ground beneath us might still shift at any moment. I worked in Louise’s studio during the day, hemming skirts, adjusting suits, sewing brides into dresses they would remember in photographs for decades. At night, after the children fell asleep in that narrow bed, I designed my own patterns by the faint yellow light of a lamp: dresses I imagined elegant American women wearing to ballrooms, to fancy dinners, to embassy events I’d only ever glimpsed on the news.

Anthony was tried, convicted, and sentenced to eight years for fraud and conspiracy. Edward, as the mastermind, received more. The day the newspaper printed their sentences, I clipped the article and put it away, not as a trophy but as proof. One day, when the children were older, they would need to see that wrong choices have real consequences.

When Michael asked if we could visit his father, I said yes.

I would not be the one to turn their hearts hard.

The first time we visited the facility, the clank of metal gates and the stark American flag hanging over the entrance made my throat close. Seeing Anthony in that environment—thin, hair grayer, dressed in plain clothes instead of his tidy suits—shook me more than I expected.

“Are you all right?” he asked, eyes flicking from me to the children and back again.

“We’re starting over,” I said evenly. “The children are in school. I’m working. That’s what matters now.”

He spoke of regret and of plans that “got out of control.” I listened without responding. He had never believed I could survive without him. It was starting to dawn on him that I not only could—I already was.

Time passed. The United States changed around us—new administrations in the White House, new policies, new headlines. My children grew. My client list widened. I rented a small apartment near the studio, then a slightly bigger one. I made curtains from leftover fabric. Michael painted the walls. Teresa drew flowers all over her notebooks and started sketching dresses that looked better than some of mine.

And then, one afternoon two years after the note fell from the Bible, the past showed up at my apartment door with rain dripping off her hair and a baby in her arms.

When Michael opened the door and said, “Mom, there’s a lady here with a baby,” I wiped my hands on my apron and walked to the entrance, expecting a client or maybe a lost neighbor.

Instead, I saw her.

Maryanne.

She was thinner than in the picture I’d imagined, with tired eyes and hair pulled back carelessly. The baby—barely ten months old, round-cheeked and sleeping, lashes thick against his skin—rested on her shoulder. For a moment, we just stared at one another, two women connected by one man’s lies, standing in a narrow hallway in the capital city of the United States while traffic hummed outside like nothing unusual was happening.

“I’m sorry to come like this,” she said at last, her voice barely above a whisper. “I didn’t know where else to go.”

I stepped aside.

“Come in,” I said. “You’re soaked.”

I didn’t know exactly why I did it. Maybe it was the sight of the baby, innocent to the way his existence had begun. Maybe it was the way her hand shook as she clutched him tighter. Maybe it was because I knew exactly how it felt to have your whole life jerked out from under you by someone you trusted.

We sat at the small kitchen table. I watched her hands cradle the mug of tea as if it was the last warm thing she had left in the world.

She told me everything.

How the rented house in Richmond had been taken back the week after the scandal broke. How her parents, in Norfolk, had taken her in with disapproval and then kicked her out when the baby was born, calling him names I refused to repeat in my mind. How she had tried to find work as a teacher and been turned away again and again once employers recognized her last name and her connection to the bank scandal that had made the papers.

And then she showed me the letter.

Maryanne,

circumstances have changed. When I am released, I will need to start from nothing. I won’t be able to support you and the boy as I said. It’s better we go separate ways. Take care.

Anthony.

I felt no surprise.

Of course he had promised to come for her.

Of course he had promised to fix everything.

Of course he had broken that promise the moment it became inconvenient.

“I heard you started a studio here,” Maryanne said, voice cracking. “I’m not asking for pity. I’m asking for work. I can clean. Handle customers. Keep the books. I just need a chance. For him.” She looked down at the baby. “For Charles.”

The baby shifted slightly in his sleep. For the first time, I really looked at him. At the shape of his nose. The curve of his mouth. The faint echo of Michael’s features there.

He was their father’s son.

He was also my children’s brother.

Sister and brother are words you don’t ignore easily.

“Do you know anything about sewing?” I asked.

She shook her head. “No. But I learn quickly. I was good with numbers at school. I organized my last classroom perfectly. I can keep things tidy. I can keep a schedule. I’ll do anything.”

I took a deep breath.

“I have a storage room behind the studio,” I said slowly. “Right now it’s full of boxes and fabric. It’s small, but it can hold a mattress and a crib. If you help in the studio, I’ll pay you what I can. You can stay there until you have your feet under you.”

Her eyes filled with tears, spilling over despite her best efforts.

“You would let me stay here? After everything?” she whispered.

“I’m not doing it for you,” I said, the words coming out more gently than I expected. “I’m doing it for that baby. And maybe for myself. I have carried anger long enough. It’s too heavy.”

That night, after the children had met Charles and accepted, with the strange cheerful practicality of kids, that they now had a baby brother who lived in the back of the studio, I lay in bed and stared at the ceiling.

In America, people loved stories about revenge. They made movies and wrote books where the wronged woman made everyone pay.

I could have turned Maryanne away.

I could have left her standing in the hall, taken some dark, bitter comfort in the idea that she was finally experiencing what she had helped me experience.

Instead, I chose something else.

I chose to build.

We became an unconventional household very quickly. The neighbors were confused. The landlord probably thought we were distant relatives. We didn’t explain. We didn’t owe the world that.

Maryanne organized the studio like she’d been born to manage businesses. She created filing systems, scheduled appointments with a precision I’d never had time for, kept a ledger that made my accountant later say, “Whoever did this missed their calling.” I taught her to sew in the evenings, our hands moving over fabric while Charles crawled around at our feet and the older children did their homework at the table.

Customers came, then returned, then brought their friends.

“Confections by Gertrude,” one woman called it, admiring her dress in the mirror.

“It’s more than just me now,” I said, glancing at Maryanne arranging pins in a box. “We’re a team.”

Not long after, a client with a boutique in a better neighborhood suggested something that terrified and thrilled me at once.

“You should open your own place,” she said. “Not just a studio in the back of a building. A real storefront. On Madison Avenue. You have the talent. I have the capital. Let’s do something.”

I took the proposal home and laid it out on the kitchen table where so much of my new life had been decided.

“It’s risky,” Maryanne said, always the one to weigh numbers carefully now. “Rent, staff, supplies. But if it works…” Her eyes slid to the children’s closed bedroom door. “It could change everything for them.”

We argued. We calculated. We dreamed. We imagined an American store with glass windows, mannequins dressed in our designs, a sign with our name on it.

“We can’t call it just Gertrude,” I protested half-heartedly when the subject of the name came up. “You’re part of this.”

She smiled. “Your name carries the story. Mine will carry the numbers.”

In the end, we compromised.

Atelier Gertrude.

The day we opened the door to our small boutique on Madison, in a space we had painted ourselves and filled with secondhand furniture and fresh flowers, I felt something inside me settle that had been restless since the Bible fell.

We weren’t just surviving anymore.

We were thriving.

In the years that followed, our lives grew in directions I could never have guessed while I sat on the floor of my Virginia bedroom holding a note that made my hands shake.

Our dresses appeared in local magazines. A bride’s gown we designed was photographed for a little feature in a women’s magazine on “Capital City Style.” Women whispered about us at embassy parties. A few even brought us pictures torn from glossy New York publications and said, “Can you make something like this but more… us?”

Meanwhile, the children grew.

Michael excelled in math and science, building tiny models of bridges on the living room floor and talking about aerodynamics and structures. He started saying words like “engineer” and “MIT” as if they were everyday words.

Teresa turned her constant doodling into something more serious, sketching outfits on notebooks, designing patterns, experimenting with color like she saw the world in fabric instead of paint.

Charles bounded through life with the open, unaffected joy of a child who had no memory of scandal, no memory of secrets—only a childhood shaped by two women who worked very hard so he would never know hunger or shame.

Sometimes I would watch the three of them from across a room—Michael showing Charles how to fix a toy, Teresa pinning fabric to a doll, Charles laughing—and feel a strange ache. The man whose choices had once controlled our lives was now a distant figure in all of theirs.

Then the day came when he returned.

It was a summer afternoon. The boutique had expanded by then to a larger space. We had employees. We had a small corner office I used to draw designs and sign contracts. Our receptionist came to my door, a peculiar look on her face.

“There’s a gentleman here to see you,” she said. “He says his name is Anthony Miller.”

The pin between my fingers slipped and pricked my finger. A tiny dot of red rose like an exclamation mark.

“Ask him to wait,” I said.

For fifteen minutes, I made a woman’s graduation dress sit perfectly on her shoulders. I smiled, I pinned, I adjusted, I complimented. When she left, I closed the door gently and stood for a moment, breathing.

Then I went to reception.

He looked smaller than I remembered. Older. His once-black hair had faded to gray; his face had lines carved around the mouth and eyes. He wore a simple suit that was slightly out of style, like it had been bought before prison and carefully stored away.

“Gertrude,” he said, standing as if we were meeting at a social event instead of at the threshold of a history only we fully knew.

“Anthony,” I replied. My voice sounded calm even to my own ears. “Let’s talk in my office.”

Leading him through the boutique felt surreal: past racks of clothing I had designed, past employees who assumed he was a client, past a framed magazine page with our dresses and my name in print.

“You’ve built quite a place,” he said, sitting down in the chair across from my desk. His eyes flicked to a photograph of the children at the edge of the table.

“Yes,” I said. “What do you want?”

“To see my children,” he said simply. “If they want to see me.”

They were no longer the small kids he’d hugged too tightly on the morning of the transfer. Michael was a teenager now, serious and focused, filling out college applications. Teresa was blossoming into a young woman, her sketchbooks stacked high in her room. Charles… Charles was the boy who called me “Aunt Gertie” and had no idea that the man in my office had once written a letter walking away from him.

“I won’t decide for them,” I said. “They are old enough to choose. As for Charles… that’s Maryanne’s decision.”

A flicker of something like pain crossed his face at her name.

“And you?” he asked after a moment. “Are you with anyone now?”

My eyebrows rose. “That is not your concern,” I said. “It hasn’t been for a long time. I am… happy. Despite you. Not because of you.”

He swallowed. “I thought about you in there,” he said. “About what I did. I was a coward. I convinced myself that you would be better off—”

“You convinced yourself of a lot of things,” I said softly, cutting through his words. “It doesn’t matter now.”

That night, at home, I told the children and Maryanne that he was back.

The air in the room changed instantly.

“I don’t want to see him,” Michael said, the words coming fast. “Not now. Maybe not ever.”

“I think I need to,” Teresa said quietly. “Not for him. For me. I have questions only he can answer.”

Maryanne pressed her lips together. “If he wants a relationship with Charles,” she said, “it will be on my terms. There will be rules.”

Over the next weeks, they met him—one by one, in public places, on park benches and at coffee shops. Teresa returned from her meeting with a complicated expression, eyes red from tears she refused to let fall.

“He cried when he saw my drawings,” she said. “He said he always knew I’d be an artist. I don’t know whether to feel touched or angry.”

“Both,” I told her. “You’re allowed both.”

Charles met him last, too young to understand the full picture, just enough to know that this quiet man with tired eyes shared his laugh and the angle of his chin. They threw a baseball together in a park one Sunday. Later, Charles said, “He’s nice, but I already have everything I need.”

Soon, Anthony became a faint presence at the edges of our lives—a man who lived alone in a modest apartment, worked as an accountant for a small company, occasionally attended important events like graduations, standing on the far side of a proud crowd, clapping for the children whose lives had grown without him.

The years rolled forward.

Michael did go to MIT, crossing the country for his education and returning with a degree and dreams of building structures that would stand long after their makers were gone. Teresa studied design and came back to the studio with fresh ideas that scared and excited our more traditional clients. Charles studied business and took over much of the daily running of the growing company, transforming the systems Maryanne had once created on scrap paper into full-fledged models that would have impressed top executive offices in New York.

One quiet afternoon in 1980, the receptionist knocked on my office door again.

“There’s a couple here,” she said. “They’d like to speak to you about a wedding dress. The gentleman says his name is Edward Harrison.”

For a second, I thought I’d misheard.

Edward.

The man whose handwriting had once ordered my death on a scrap of paper inside a Bible. The man whose scheme had almost taken my life, my children’s safety, my future. The man I had last seen, pale and worn, leaving my studio years earlier after begging my forgiveness.

I walked into the fitting room.

He stood beside a woman about his age with kind eyes and a blush on her cheeks. He was smaller somehow, humbled in his posture, dressed simply, his hair more gray than dark now.

“Mrs. Miller,” he said, voice controlled but nervous. “This is Helena. We’re getting married next month. She… she insisted on meeting the woman everyone in D.C. says is the best at what she does. I wasn’t sure you would even agree to see us.”

Helena smiled, squeezing his hand. “He told me everything,” she said. “About the bank. About your courage. About… the note. I know it’s asking a lot. But if you are willing, it would mean so much to have you design my dress. A dress that starts a new chapter.”

I looked at them.

At the man who had once been willing to threaten my life for his crime.

At the woman who loved him despite his past.

At the years that had stretched between who we had been and who we were now.

Once, I might have said no, still clenching my anger like a badge of honor.

Now, I saw something else: proof that people can change. That the past doesn’t vanish, but it doesn’t have to dictate every choice forever.

“Come in,” I said. “Let’s talk about what you’re imagining for your wedding.”

Later, standing in the bright light of the fitting room while pins glinted between my fingers and Helena beamed at herself in the mirror, I realized something that made my throat tighten.

The hands that were adjusting her gown were the same hands that had once shaken as they unfolded a note on a Virginia floor.

The woman who stood beside her now, offering advice on veils and flowers and timing, was not the same frightened wife who had sat on that bedroom carpet.

That woman had been all but buried.

This one had grown from that grave.

Years continued their quiet march. Anthony passed away suddenly in 1995 after a heart attack. At the funeral, we all stood together—the children, now adults; Charles with a family of his own; Maryanne and I, side by side. We didn’t mourn a romantic love. We mourned a man who had once been the center of our world and had then become a dark shadow and a distant echo.

Later, when the coffin was lowered and the small crowd dispersed under a cloudy American sky, we went home together. We made lunch. We told the children stories—not of his worst moments, but of the times when he had laughed with them, carried them on his shoulders, read them bedtime stories. You can hold the truth in its full complexity without sugarcoating it. That’s one of the things life had taught me.

Now, at seventy-eight, I sit on a porch swing in Virginia again.

The house is different—bigger than the one we lost, warmer too, paid for with honest money from a business that started in the corner of a rented apartment behind a modest D.C. studio. Children’s laughter echoes in the yard: my grandchildren chasing each other with water balloons, their shrieks rising into the summer evening air like fireworks. An American flag hangs near the mailbox, fluttering in the breeze, along with a hanging pot of flowers my granddaughter insisted we buy.

Inside, somewhere on a shelf, there’s still a Bible.

I don’t open it much these days.

Sometimes, though, when the house is quiet after a Sunday dinner, when Maryanne and I are sitting at the kitchen table with our tea, I think back to that moment: to a Bible crashing to the floor, to a note spinning through the air in a shaft of Virginia sunlight, to seven words that might have ended my life.

If she discovers the truth, kill her.

They thought that truth would destroy me.

Instead, it set me free.

I often picture that younger version of myself—a twenty-nine-year-old American woman with a headache, a cotton dress, and no idea how strong she really was—sitting on her bedroom floor with a metal box of secrets open in front of her.

If I could reach across time now, I would kneel beside her, take her trembling hands in mine, and tell her:

“Courage, Gertrude. What feels like the end of everything is the beginning of the life you were meant to live. The storm is coming, and it will be brutal, but you will survive it. You will build something bigger, brighter, and more beautiful than the small, neat life they tried to confine you to. What was meant to bury you will become the soil you grow from.”

And I suppose that is what I want to leave with anyone who somehow finds their way into my story now, whether through a screen in some American living room or words on a page borrowed from a friend.

Whatever storm you are standing in the middle of, it might not be the end.

It might be the beginning.

Sometimes, life has to crack wide open—like a Bible slamming to the floor—so the truth can slip out, land at your feet, and give you the chance to choose who you will become next.

News

I looked my father straight in the eye and warned him: ” One more word from my stepmother about my money, and there would be no more polite conversations. I would deal with her myself-clearly explaining her boundaries and why my money is not hers. Do you understand?”

The knife wasn’t in my hand. It was in Linda’s voice—soft as steamed milk, sweet enough to pass for love—when…

He said, “why pay for daycare when mom’s sitting here free?” I packed my bags then called my lawyer.

The knife didn’t slip. My hands did. One second I was slicing onions over a cutting board that wasn’t mine,…

“My family kicked my 16-year-old out of Christmas. Dinner. Said ‘no room’ at the table. She drove home alone. Spent Christmas in an empty house. I was working a double shift in the er. The next morning O taped a letter to their door. When they read it, they started…”

The ER smelled like antiseptic and burnt coffee, and somewhere down the hall a child was crying the kind of…

At my daughter’s wedding, her husband leaned over and whispered something in her ear. Without warning, she turned to me and slapped my face hard enough to make the room go still. But instead of tears, I let out a quiet laugh and said, “now I know”. She went pale, her smile faltering. She never expected what I’d reveal next…

The slap sounded like a firecracker inside a church—sharp, bright, impossible to pretend you didn’t hear. Two hundred wedding guests…

We Kicked Our Son Out, Then Demanded His House for His Brother-The Same Brother Who Cheated with His Wife. But He Filed for Divorce, Exposed the S Tapes to Her Family, Called the Cops… And Left Us Crying on His Lawn.

The first time my son looked at me like I was a stranger, it was under the harsh porch light…

My sister forced me to babysit-even though I’d planned this trip for months. When I said no, she snapped, “helping family is too hard for you now?” mom ordered me to cancel. Dad called me selfish. I didn’t argue. I went on my trip. When I came home. I froze at what I saw.my sister crossed a line she couldn’t uncross.

A siren wailed somewhere down the street as I slid my key into the lock—and for a split second, I…

End of content

No more pages to load