The probe stilled like a held breath, and the blue-gray image on the ultrasound screen turned to static quiet—the kind of quiet that has edges. Rachel Monroe watched the white ceiling tiles become a grid she could hold onto. The room hummed the way Phoenix exam rooms hum, air conditioning steady, fluorescent lights flattened into obedience. Dr. Caleb Wright leaned in, his eyebrows tightening, his mouth forming a thin line that wasn’t there a second ago.

He didn’t speak. Doctors know silence can be a conversation—sometimes the last kind you want.

“Is something wrong?” Rachel asked, her voice almost calm, as if calm would coax the machine into saying it was mistaken.

Dr. Wright adjusted the screen’s angle and looked again. He set the probe down with the kind of care people use for delicate objects that might break or explode. When he turned toward her, his voice was low and controlled, each word placed like a measured dose.

“Rachel, I need you to listen carefully,” he said. “What I’m seeing inside you shouldn’t be there.”

Her heart began to pound in a rhythm that felt foreign. “What do you mean?” she whispered.

He stood slowly, as if abrupt movement might offend something invisible between them. “There is something in your uterus that does not belong there,” he said. “It isn’t natural tissue. It isn’t a benign growth. It looks like a foreign object that’s been inside your body for a long time.”

The cold arrived everywhere at once. Words tilt when they become new weather: foreign object.

Dr. Wright nodded once, not to push the words closer but to set them gently where she could see them. “And the fact that it is there raises serious questions about how it got inside you,” he continued, “and who put it there.”

It is astonishing how fast a life can crack. One sentence. Two tiles of a ceiling you didn’t know were heavy. A face that changes angle and makes a room different forever.

Until that moment, Rachel had never questioned the man she had built her life around. Andrew Monroe was not just her husband. He was her doctor, the voice she trusted over her own when it came to her body, the steady hand at his private women’s health clinic in Phoenix—the clinic with mid-century chairs and desert light pulled cleanly through tall windows. Patients praised his calm tone, his careful explanations, the way he could make pain sound like a puzzle waiting to be solved. Friends called them solid and steady, the couple who didn’t argue in public and always arrived together.

For fifteen years, the appearance had been a kind of shelter. Andrew had a practice where the waiting room played soft music and the staff knew how to say hello correctly. He would tell Rachel, when she winced, that bodies tell stories and hers was telling a normal one. He would say her hormones were changing, cycles shifting, stress doing tricks, and he would sound so certain that concern began to feel like misbehavior.

“Trust me,” he said often, smiling the smile she’d married. “I know your body better than anyone.”

So she did. She trusted him when the cramps sharpened and wouldn’t go home on time. She trusted him when bleeding ignored calendars and then forgot to come at all. She trusted him when exhaustion discovered the switch that kept it on. She trusted him when he said scans weren’t necessary, when he said tests would only create anxiety, when he pressed a pill into her palm as if comfort were a dosage.

Rachel wanted to be a mother. Not immediately, back then, but eventually—on a schedule that felt like theirs. Andrew agreed in principle, and gently moved the future further: first, we build our life; first, we get comfortable; then there will be time. He had a way of placing later like a pillow.

Looking back now from a dim room with humming machines, Rachel could name what she hadn’t named before: how much power she had handed over without noticing. She had given Andrew the keys to her home, her heart, and her health—three doors that, when one person holds all the locks, make danger feel theoretical. When someone controls all three, you don’t think to look for danger. You think you are safe.

For six months, the pain had been a new language that translated her days into something smaller. It arrived in waves, sudden and precise, like a hand closing from inside and refusing to release. Some mornings, she could barely stand straight; other days, she straightened out of loyalty to normal and walked into work pretending she wasn’t counting minutes. Bleeding came without warning and left with its own logic. It was deeper than discomfort, heavier than stress, more constant than age. And Andrew’s answers were wrapped in calm sentences that made her feel silly for worrying.

“It’s normal for women your age,” he would say. “Hormones shift. Stress does strange things to the body.”

He said it so gently that Rachel began to doubt the part of her that was trying to tell her something real. What business did she have, questioning a man with decades of practice? What does a patient do when the doctor is also the person who tucks her in?

But inside the language of reassurance, a quiet voice began to insist: Something is wrong. It wasn’t theatrical. It was patient. It did not argue. It kept returning. The voice spoke in the details: the pain was not like any pain she had known; the presence of a constant grip felt like possession; the fact that Andrew never ordered tests anymore, never suggested scans, never referred her away even when her symptoms behaved like symptoms that needed machines—those omissions were their own kind of diagnosis.

One night in August—the desert heat pushing night toward morning and then forgetting to stop—Rachel sat on the bathroom floor and shook. Andrew gave her medication and told her to rest; he spoke in the tone that had gotten him through hundreds of hard conversations in exam rooms. She followed his instructions. But fear settled into her chest like a tenant with first and last month paid. Bodies don’t scream without a reason, she thought. Whatever this is, it isn’t just age or stress. It is something else. Something hidden. Something nobody is naming.

Phoenix is a city that can hide things with light. The next morning, the light was ruthless and honest and she chose to believe it. She waited until Andrew left for a medical conference—the kind of conference where he would stand in a hotel ballroom beneath recessed lights and talk about outcomes—and then she made the call her life had been preparing to make for months.

Her hands shook when she booked the appointment with Dr. Caleb Wright. It felt wrong to go behind her husband’s back; it felt wrong to be the person who didn’t tell the person she had always told everything. But the pain had pushed her past polite. Past fear. Into the necessity of a second opinion.

Dr. Wright’s clinic was across town—closer to downtown, in a modern building with bright windows, clean white walls, chairs that don’t pretend to be chic, and staff who say names like they belong to someone. Nobody there knew her. Nobody there had any reason to protect Andrew. The unfamiliarity felt like safety.

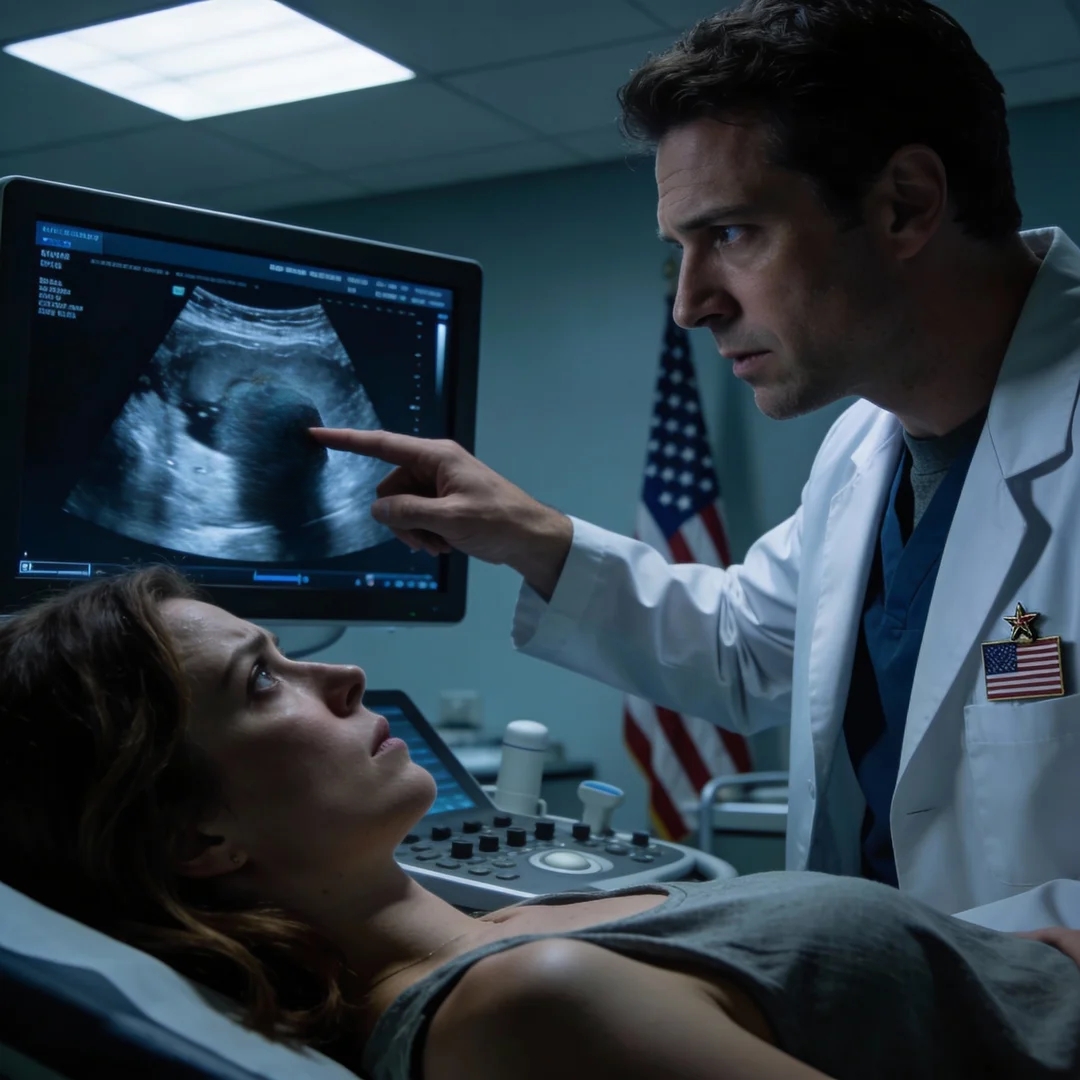

Dr. Wright listened the way good doctors listen: with interruptions avoided, hands folded—the kind of posture that says we have the time this takes. Rachel described the symptoms. She didn’t dramatize them. She didn’t minimize them. He nodded, then suggested an ultrasound. The room dimmed. The screen’s light took over.

At first, Rachel did not understand what she was looking at. Ultrasound images are confidence tests. They ask you to believe in ghosts. Dr. Wright adjusted the probe, changed the angle, looked longer than any previous doctor had looked, then stopped. On the screen, Rachel could see a dark, irregular form where none should have been. The silence grew into shape.

“What is that?” she asked, a simple question that felt like an opening in a wall.

Dr. Wright took a slow breath and did not equate her courage with anxiety. “There is something inside your uterus that should not be there,” he said. The machine hummed. Phoenix light pressed against the closed blinds and failed to climb in. “It looks like a foreign object. Something embedded in tissue over a long time.”

“I’ve never had anything inserted,” Rachel said quickly. “I am—afraid of those kinds of devices. My husband knows that.”

Dr. Wright considered the sentence, then placed it gently where it belonged. “Then we need to find out how it got there,” he said, not adding any drama to a reality that didn’t need it.

He moved away from the screen and sat across from her. Calm has gravity when it’s deserved; his had weight. “I want to run blood work and more detailed scans,” he said. “The tissue around the object appears inflamed. That usually means it’s been present a long time and your body has been reacting to it.”

“Is it dangerous?” Rachel asked. The room was small enough for fear to be measurable.

He was honest without cruelty. “It can be,” he said. “Chronic inflammation inside the uterus can lead to complications—infection, scarring, and in some cases changes that increase risk of cancer.”

The word landed the way some words do: accurate, devastating, lightless. Rachel’s breath caught like a dress on a nail.

He printed a referral and slid it toward her. “You need to go to the county hospital today,” he said. “They have the surgical team and imaging equipment to remove this safely. I don’t recommend waiting.”

“Remove it,” she said, as if repetition could negotiate with nouns.

“Yes,” he said simply. “Whatever this is, it does not belong in your body.”

He didn’t ask her who she thought had done it. He didn’t accuse anyone. He didn’t gossip. He did medicine.

“How could something be inside me without me knowing?” she asked. She wasn’t asking for comfort. She was asking for physics.

“The only way a foreign device ends up inside someone is if another person put it there,” he said, as neutral and terrifying as a textbook line. “And given your history, I recommend you speak with the police. Inserting a device without consent is a serious crime.”

Crime echoed in her mind with the persistence of a fire alarm. She left the clinic with the referral in her hand. That morning, she had been a woman with unexplained pain. By lunch, she was a woman being told that the pain had a cause that belonged to intention. The difference between those categories is the difference between doubt and clarity, between self-questioning and rage, between marriage and a courtroom.

In the parking lot, she sat in her car, keys on her palm. The desert air pressed against the windshield like an argument. Only one person, historically, had held certain kinds of access. Only one person had been present every time she was vulnerable. The thought was more terrifying than any diagnosis. It was also a thought that refused to leave.

The county hospital admitted her within hours. The building had the smell hospitals have when they are busy and honest—cleaners and coffee and information. Everything moved quickly, in a blur of forms, bright lights, voices designed to cut through panic. A nurse asked her to sign. A resident asked her to rate her pain. A surgeon introduced himself with the sentence surgeons use when they are about to ask you to trust them with everything.

“Dr. Leonard Hail,” he said, steady voice, steady eyes. “We will remove the foreign object and clean the surrounding tissue. The inflammation appears severe. We’ll take samples for testing as we go.”

Rachel nodded. Fear twisted and then stopped trying to make loops. She had experienced fear before, in small doses, in the shape of unknowns. This fear was larger. It had an address. She let herself be wheeled into a room where lights do not pretend to be sunlight, where machines wear their purpose out loud.

Anesthesia smoothed out the edges. The world went away as politely as it could.

When Rachel woke, her throat was dry and her body felt heavy, the way bodies feel when they have agreed to be cared for in a way they cannot control. Dr. Hail was there, the kind of presence you want to return to. “The procedure was successful,” he said. “We removed the object.”

He held up a clear container. Inside was a dark metal device, a small twisted frame that looked like it had been designed by a committee that forgot to include compassion. It looked old, the edges corroded. The sight of it made the room feel colder than its thermostat could explain.

“That was inside me?” she asked, disbelief performing itself and then exiting.

“Yes,” Dr. Hail said, neutral. “And it has been there for many years.”

“What is it?” Rachel whispered.

“An intrauterine device,” he said, not softening the word. “But not a modern one. This is an old model that was banned more than a decade ago because of associated risks.”

“Risks like what?” she asked. The small questions are the ones that change streets.

“Chronic inflammation,” he said. “Increased risk of certain cancers.” He met her eyes and did not flinch away. “It also has a serial number. We can trace where it came from.”

He explained that the surrounding tissue showed signs of damage—evidence of an ongoing fight her body had been losing slowly. They had taken samples to test for abnormal cells. “We caught this just in time,” he said. “But you will need close follow-up.”

Rachel turned her head away and stared at the seam in the curtain. The seam looked like it had been stitched by a person. For years, something dangerous had been inside her, installed by intention or by negligence or by a hatred masked as care. Someone had placed it there. That sentence would require years of living to absorb.

That same evening, a woman in a dark suit stepped into Rachel’s hospital room. The badge caught the desert light angling in through a high window. “Detective Sophia Grant,” she said. The voice was calm and respectful, designed for rooms where truth cannot be hurried. She asked questions with the precision of someone who wanted to build something that would stand.

“Who had access to you when you were unconscious?” she asked gently.

Rachel did not need long. “Eight years ago,” she said, the timeline arriving like a repeat prescription. “I had my appendix removed. My husband insisted it be done at his clinic. He said he would supervise everything himself.”

Detective Grant wrote it down with a pen that wasn’t interested in performance. “Did anyone else treat you that day?” she asked.

“I don’t know,” Rachel admitted. “Andrew handled everything.”

The detective nodded slowly, the way people nod when a piece fits. “That’s important,” she said. She did not promise outcomes. She promised process.

A few hours later, she returned with news that did not knock so much as sit down on the bed beside Rachel and refuse to leave. “The device we removed has been traced,” she said. “Its serial number was logged as destroyed eight years ago at your husband’s clinic.”

Rachel closed her eyes. The room did not change. “So it came from him,” she whispered, the sentence landing not as accusation but as gravity.

“Yes,” Detective Grant said. “And the records show he personally signed off on its disposal.”

Rachel felt grief and relief arrive at the same time and try to figure out how to share a chair. Grief because the truth was a kind of violence. Relief because she had not hallucinated the shape of the story. She had doubted herself for months. Doubt is exhausting. The chance to stop doubting felt like oxygen.

“Your tissue tests also came back,” the detective added, not dramatizing. “You have severe precancerous changes caused by long-term exposure to that device.”

Rachel’s hands trembled with something that was not fear and not anger and was both. “If you had not gone to Dr. Wright when you did,” the detective continued, “you would likely have developed cancer within a year or two.”

The words settled heavy. They did not leave. They obeyed physics.

“We’re opening a criminal case,” Detective Grant said, and the sentence felt like someone finally decided to lift a weight that had been sitting on Rachel’s chest for years. A case number would be assigned. A prosecutor would receive a file. A courtroom would make room for chairs. The next part of her life would not be private anymore.

Three days after surgery, Rachel left the hospital with instructions she would follow and a new kind of courage she had not asked for. She drove to Andrew’s clinic because Detective Grant had given her permission to retrieve personal items and look for documents related to her care. The building was quiet like buildings are quiet when they have secrets, the kind of silence that feels curated. She walked inside. The hallway wallpaper had a familiar pattern. In Andrew’s office, everything was where it had been for years—the desk that made him look stable, the diplomas that framed his expertise, the photos of trips where Rachel had smiled for cameras that didn’t ask questions. It was a perfect stage for denial.

As she searched, a young woman stepped into the doorway. Scrubs. A badge. Eyes that looked like they had not slept. Rachel recognized her. “Emily Ross.”

Emily startled at the sight of her. “Dr. Monroe said you were still in the hospital,” she said, the sentence tripping lightly over itself.

Rachel’s eyes moved to what Emily held. A pregnancy test. A small rectangle with the power to rename futures.

“Is it his?” Rachel asked softly, not angry yet, not patient anymore.

Emily froze, human instinct trying to calculate which truth would be punished. Rachel noticed the ring. Nearly identical to her own—same band, same stone, same taste purchased twice. “He promised he would leave you,” Emily whispered. “He said you couldn’t have children. He said your marriage was already over.”

Illusion is stubborn; it didn’t break. It dissolved, ceilings and promises and birthdays rearranging themselves. Rachel felt the new picture assemble: Emily had two children with Andrew—a boy named Noah and a little girl named Lily. He supported them. He visited. He had built a second life in the same city where Rachel’s first life had been being reduced. While Rachel was suffering, he was becoming a father who brought balloons to parks and took photos on swings.

The cruelty was arithmetic. The man who had taken her chance at motherhood had given it freely to someone else. The equation didn’t look complicated until you tried to solve it without crying.

Rachel left the clinic with her mind spinning and drove straight home. For the first time in years, she walked into Andrew’s private office and sat at his computer. Trust had kept her out of this room. Reality invited her in. She guessed the password. It was his mother’s birthday. It took two attempts.

A folder on the desktop caught her eye—Forever Now. Inside were hundreds of photos. Andrew holding two small children. Emily smiling beside him. Family trips with desert sunsets and cake alarms. Birthdays. Holidays. Parks. The images were average—the kind that make social media content for people who don’t know they’re telling the truth in the wrong room.

The messages were worse. Rachel opened one and felt her stomach drop in a way that had nothing to do with surgery. Don’t worry, Andrew had written. I solved the problem with Rachel during her surgery. She will never have children, and we can build our life together without complications.

There were bank records, monthly payments to Emily for their children. An apartment in her name. Insurance policies. He had planned everything. He had taken control of Rachel’s body so he could live another life. He had written out the logic of his crime in sentences that didn’t know they were crimes.

Rachel copied the files to a flash drive. These were not just secrets. They were proof. Proof is cruel when it is this clean. Proof is also kind when it needs to be. Proof would destroy him.

Andrew came home that evening carrying flowers as if the ritual had a chance. He smiled when he saw Rachel sitting in his office. “There you are,” he said, voice soft with practice. “I was worried about you.”

Rachel turned the computer screen toward him. The messages were there. The photos did their job. His confession stood all the way up.

“What is this?” he asked, mildly, like a person discovering a bill they didn’t remember approving.

Rachel held up the clear container from the hospital—the twisted frame visible through plastic. “This is what you put inside me,” she said, without raising her voice. “This is what has been destroying my body for eight years.”

Andrew stepped forward, reaching for the container because people reach for objects as if grabbing them can grab time. “Give me that,” he said.

Rachel moved back, a small step that felt like an ocean. “You stole my right to choose,” she said. “You stole my health so you could have children with another woman.”

Andrew opened his mouth to speak, but before his version of the story could enter the air, the front door burst open. Detective Grant walked in with two officers. The desert light fell across badges. Procedure assembled itself.

“Andrew Monroe,” she said, clear, professional, equal parts apology and certainty, “you are under arrest for causing serious bodily harm and medical assault.”

Andrew’s knees bent toward the floor, a gesture that wasn’t quite collapse and wasn’t quite humility. Emily rushed in behind them, crying, a flood of sentences arriving naked: how he lied to her, how he said Rachel was infertile, how he promised to leave, how promise became a schedule he didn’t honor. The officers did their job. They led him away in handcuffs.

Rachel watched him go. Relief is not always loud. Sometimes it is a silence that finally has permission to be silence.

The courtroom would be packed later—doctors, reporters, curious strangers, Phoenix citizens who treat courtrooms like civics classrooms. But that is Part 2’s work. For now, the story sits in a clean line: an ultrasound room where a probe stilled, a county hospital where a banned device came out of a body, a badge that promised a file, a computer folder that thought it was a secret, a hallway where a woman stood and realized the world had changed without asking her.

The night was wider than her apartment walls. Phoenix’s desert air moved without noticing funerals. Rachel stood in the middle of a living room where she had lived a life and thought about future tense. Morning would arrive precisely when it was scheduled. Doctors would write notes. Detectives would add case numbers. Lawyers would prepare to ask questions. And somewhere, in a room with soft lights and stainless steel, a device that had been inside her for eight years would sit in a small clear container and hold its shape without dignity.

“We caught it just in time,” Dr. Hail had said. He meant cells and scans. He didn’t know he was also talking about Rachel’s life.

Outside, the desert turned orange, then cooled. Inside, the flash drive sat on the desk. Evidence is patient. Justice is procedural. Grief is tireless. Relief takes naps.

Rachel poured a glass of water, drank, and set it down with care. The glass made a small sound against the table, the kind of sound that tells you your hand is steady. She breathed, not because someone told her to, but because breath had returned as a thing she could trust. She turned off the computer, which is an act of mercy when those screens have been used to hurt you.

By morning, the desert light had the courtesy to arrive on schedule. Rachel woke before the alarm and lay still long enough to measure the quiet. Hospitals have a different kind of silence; courtrooms do too. Home was learning a third—emptier than grief, steadier than shock. She made coffee and stood at the window until the cup cooled enough to drink.

The phone vibrated once: a number labeled “Detective Grant.” She answered.

“Good morning, Ms. Monroe,” the detective said, carrying her clipped calm into the day. “We’ve opened the case. Maricopa County assigned a number, and the District Attorney’s office has a preliminary intake. I’ll walk you through the next steps.”

Rachel breathed. “I’m ready.”

“We’ve secured chain-of-custody for the extracted device,” Grant continued. “The serial number matches the lot destroyed at your husband’s clinic eight years ago. We’ll obtain a full set of records and interview staff. You won’t need to be present for that phase, but I will keep you updated.”

“What do you need from me?” Rachel asked.

“A formal statement,” Grant said. “Your recollection of the appendectomy timeline and the symptoms thereafter. Also, any documents you recovered—emails, financials—should be duplicated and given to us. Keep a copy for your attorney. We already obtained a warrant for clinic systems and storage. We’ll coordinate with hospital counsel to protect your privacy.”

“Okay.” The word felt level. Rachel looked at the flash drive on the table, its small weight in the vastness of what it represented.

They met that afternoon at a precinct that believed in good chairs and strong coffee. The interview room was painted a color meant to be invisible. Grant recorded; a stenographer typed the sound of a life being organized into a record. Rachel spoke slowly, the way truth moves when it refuses to embellish itself: the night in August when the pain sent her to the floor; Andrew’s pills and assurances; years of being told tests weren’t necessary; how a second opinion saved her life.

She handed over a duplicate of the flash drive, a printed index, and a brief note she’d written for herself to keep faith with facts: the date of the appendectomy, the name of the anesthesiologist she remembered from the consent form, the time Andrew had signed her discharge papers with a flourish she once found charming.

“Try to rest after this,” Grant said, packing the evidence with a patience that felt like respect. “We’ll be in touch.”

The investigation moved the way good investigations move: forward, increment by measured increment. A subpoena to the clinic for disposal logs and surgical records. A knock on doors where people in scrubs remembered a day they hadn’t known they would need to remember. A copy of an anesthesia ledger that listed staff present during an appendectomy that had felt like a routine day in a room full of routines.

Staff spoke. Nurses described Andrew’s habit of being everywhere at once. A surgical tech recalled a tray—sterilized, unused—logged as “disposed,” then “destroyed,” the kind of double-verb hospitals use to reassure themselves twice. One of the clinic’s administrators, an organized man who loved forms, turned pale when he found the signature—Andrew’s—approving the destruction of a device whose serial number matched the one in the county hospital’s evidence room.

The device itself—improper, banned, and now inert—sat in a clear container in a cool cabinet, cataloged, its presence a quiet insult to every decent room it occupied. A lab report arrived with the same dry authority that had saved Rachel’s life: inflammation consistent with prolonged foreign body; precancerous changes severe but localized; margins clear after extraction. The words were boring and beautiful.

Grant called with updates in a voice that honored both sides of Rachel’s life—the private one that needed rest and the public one that would insist on procedure. “We’ve processed the messages you found,” she said. “The statements are clear. Payments are documented. We’re coordinating with the DA on charges: medical battery, aggravated assault, evidence tampering. The bar association has begun their review.”

“Will I have to testify?” Rachel asked.

“Yes,” Grant said. “But we will prepare. You won’t be alone.”

Rachel thanked her and meant it. After the call, she sat with a notebook and wrote what she needed to keep straight: dates; names; a line for Emily—whose face had become a hinge between two houses—and the names Noah and Lily, who had not chosen their father’s map.

Emily reached out first. A short text, simple and miserable: I’m sorry. I didn’t know. He told me you couldn’t have children. He said he’d handled it. He said he loved me. I didn’t know what handling it meant.

Rachel answered an hour later with a sentence she didn’t recognize as hers until she saw it: This isn’t your fault, but telling the truth now matters. If you’re willing, talk to Detective Grant. It will help all of us.

Emily agreed. She gave a statement that opened out into a landscape in which Andrew had paced two lives with a surgeon’s precision and a coward’s pragmatism. She didn’t protect him. She didn’t hide. She said what she knew and what she’d been told and where the money went. It was the exact currency the DA needed.

The arrest had been the loudest moment. Everything after that became the administration of consequence. Bail denied. License suspended. An emergency hearing with the state medical board scheduled; a quiet letter from the hospital ethics committee, its language antiseptic: privileges revoked. The conditions of pretrial release were academic—there would be no release.

Rachel began to experience time differently: less as a chronology and more as a list. Eat. Walk. Read. Call her mother. Return Dr. Wright’s voicemail with an update. Schedule the first post-op checkup. Take a business card from a therapist who specialized in medical trauma and place it where she couldn’t ignore it. Consider making the appointment, then make it.

At the first follow-up, Dr. Wright met her in the same room where he’d lifted silence off a screen and called it by its name. “How are you sleeping?” he asked.

“Better,” she said, because it was true, and because better deserves to be said out loud when it stops by.

“Pathology reports looked as good as we could hope,” he said. “We’ll keep a six-month schedule for the first year. Then we’ll reassess.”

“Thank you,” she said. The words were insufficient and exactly right.

He nodded and then looked her in the eye, the way men do when they have been carrying a thought that isn’t medicine. “You trusted me enough to come here,” he said. “I don’t take that lightly.”

She didn’t know how to answer, so she didn’t. Some gratitude is too heavy to lift in public. She left the clinic with a new date on the calendar and a reminder that not all doctors are dangerous in rooms where you are vulnerable.

The DA’s office scheduled a meeting with her and Detective Grant to outline the courtroom choreography. The conference room faced north, giving Phoenix’s light a chance to be diffused into something civilized. An assistant prosecutor named Lila Park—efficient, frank—laid out the structure: pretrial motions; jury selection; opening statements; witnesses in a sequence designed to build a simple bridge through complicated facts.

“We don’t need drama,” Park said. “We need clarity. The device, the trace, the records, and the statements create a straight line. That’s what we’ll present.”

“What will they argue?” Rachel asked, meaning Andrew’s defense.

Park glanced at Grant. “They’ll try to muddy consent,” she said. “They’ll imply you knew about some procedure, or that the device was placed elsewhere. They may point to your pain and suggest a predisposition to complication. They might even attempt to put the other family into evidence to argue that he’s a good father and therefore not a criminal. We will object. Most of it won’t get in. But prepare yourself: some of it might be said in the room anyway.”

Rachel nodded. She wrote in her notebook: they will try to give guilt a costume.

The court date arrived with the punctuality of the state. The courthouse smelled like paperwork and metal. In the hallway outside the courtroom, a murmuring crowd formed—reporters with legal pads, doctors with folded arms, curious strangers who treat court as theater. Rachel took a seat in the front row. Andrew entered with his lawyer. He looked smaller and therefore more dangerous. He did not look at her.

The judge was the kind who preferred order to all other virtues. Jury selection proceeded with the dignity of ritual. Opening statements traced two narratives: the state’s simple one, Andrew’s counsel’s complicated one. Then the witnesses.

Dr. Caleb Wright went first. He explained what he saw on the ultrasound and what he did next. He used no adjectives. He described the image, the foreign object, the referral to the county hospital, and the standard of care. He did not speculate. The defense tried to cross-examine him into offering opinions about Rachel’s underlying health. He refused gently. “I can tell you what I saw, what I did, and why,” he said. “Beyond that would be conjecture.”

Dr. Leonard Hail followed. He described extracting the device. He held up a photo of the object, sealed and labeled, the serial number legible even from the gallery. He explained the pathology results, the inflammation, the precancerous changes, the way time behaves when a foreign body is left in place. He never said “cruelty.” He never needed to. The jury watched the screen and watched him and watched the map between them.

A biomedical engineer testified briefly about the device’s history—how certain models had been banned years ago due to risks not just of inflammation but of systemic complications. He spoke in a tone that made even the word “recall” feel like a moral action.

Then, Detective Sophia Grant. She narrated the chain-of-custody as if she were telling a story about furniture moving from one apartment to another without being scratched. She explained the serial trace: logged as destroyed at Andrew’s clinic; signed by Andrew Monroe; contradicted by the device’s presence in Rachel’s body. She described the clinic records, the anesthesia logs, the staff statements. The DA introduced emails and financial records from Andrew’s computer. The words Andrew wrote to Emily appeared on a screen the size of a wall. The defense objected. The judge allowed the messages in for the limited purpose of establishing motive and knowledge. The jury looked and did not look away.

Emily Ross took the stand. She held her hands in her lap like a person mindful of gravity. She told the court what Andrew told her: that Rachel had been born unable to have children; that the marriage was over; that he had “solved” the problem; that their children were proof of a love he intended to make official; that his promises kept moving further into a future that never arrived. She did not try to exonerate herself. She answered questions with the only power she had left: the truth. When it was over, she stepped down without looking toward the defense table.

Rachel testified last. When she took the stand, the courtroom’s air changed. Victims make rooms honest in ways no ethics code can. She told the story the way a witness tells it when she respects the room: the pain; the dismissals; the quiet voice inside that refused to stop; the second opinion; the surgery; the container; the serial number; the flash drive; the arrest; the sound of handcuffs that didn’t feel like victory and didn’t feel like loss—only like the world being repaired in one small place.

“I trusted him with my body,” she said. “He used that trust to make decisions I did not consent to. Those decisions have consequences that I will carry for the rest of my life.”

The defense tried to ask if she had ever consented to any contraception at any point. She said no. The defense tried to suggest that she had been forgetful under anesthesia. The judge sustained the objection before Park had to stand. The room breathed.

Closing arguments were shorter than the press had hoped and better for it. Park pointed to the straight line: object found; serial traced; disposal log forged by a signature; messages revealing knowledge and motive; medical harm measured by lab assays, not adjectives. The defense suggested reasonable doubt in tones that had passed as persuasive in other rooms. The jury left.

The wait was the longest hour of Rachel’s life and also the easiest, because waiting is an art bodies learn when they have to. Grant sat beside her. Park reviewed a file with the brevity of someone who knows that reading the same paragraph won’t change its meaning. Andrew whispered to his lawyer. The clock on the wall kept its promise to move.

When the jury returned, the foreperson stood. The room, as rooms do when significance arrives, went still. The judge asked. The foreperson answered in words that belonged to the state but felt personal: guilty of serious bodily harm; guilty of medical battery; guilty of evidence tampering.

Andrew showed no expression until the sentence. The judge’s voice was a practiced instrument—no tremor, no anger. “You violated the most basic duty of your profession and the most basic trust of your marriage,” he said. “The law will speak for both.” Andrew’s medical license was revoked. He was sentenced to prison. Restitution ordered. Court adjourned.

Reporters tried to catch Rachel as she left the courthouse. Some asked questions they should have been ashamed to ask. She walked past them with the calm that accompanies a verdict that didn’t make you whole but made the world slightly less broken. In the shade of a palo verde, Detective Grant caught up with her.

“Are you okay?” Grant asked, knowing “okay” is a blanket we use to cover furniture that needs repair.

“I’m steady,” Rachel said.

“That’s better than okay,” Grant replied. They shook hands. It felt like the exchange you have with a person who helped you carry a piano down a flight of stairs.

Healing did not arrive like a newly painted room. It arrived like a series of small chores. Rachel learned to walk the neighborhood again without scanning every passing car. She learned the names of her neighbors’ dogs. She learned which grocery clerk stocked the good produce and what time of day the line was shortest. She bought a new mattress and slept better. She painted one wall. She replaced the rug she had always hated but never admitted to hating. Her body, given time, remembered how to be hers.

The follow-up appointments continued. Dr. Wright kept his promises of precision and restraint; Dr. Hail checked scans with a humility that made Rachel like him more. The pathology reports stayed boring, then celebratory in their refusal to surprise. She kept seeing the therapist. She learned that trauma is not an enemy to be defeated but a history to be integrated. She stopped flinching when the phone rang.

When she felt strong enough, Rachel called the adoption agency whose brochure had been quietly sitting in her mailbox months earlier, addressed to “Resident,” as if fate had intended it for anyone. She made an appointment. The office was painted a cheerful yellow that did not pretend to fix anything but helped. The caseworker—a kind woman named Brenda with a voice that had been trained to hold grief and hope without wasting either—explained the process. Background checks. Home study. References. Classes. Patience.

Rachel did paperwork the way she had learned to live: carefully, completely. She told the truth where some might have been tempted to dull it. She explained that she had wanted children. She explained that medicine can be used as a weapon and also as a cure. She explained that she was ready to love someone who needed a home.

Months passed in a cadence that felt moral. Court dates faded into the rearview mirror. The county hospital became a building she could drive by without holding her breath. The desert changed color like a competent stagehand.

One afternoon, her phone rang with a number she had saved under the label “Agency.” Rachel answered with a voice she did not recognize until later—lighter, braver.

“There’s a little girl,” Brenda said. “Her name is Grace. She’s three. She needs a home.”

Rachel sat down and put a hand on the table. “Tell me about her,” she said.

“She’s shy at first and then opinionated about everything,” Brenda said. “She likes books and the sound of washing machines. She is wary of sudden noises. She loves blueberries. She lost her parents. She needs someone whose calm is real.”

“When can I meet her?” Rachel asked.

They set a date. The room where introductions happen was soft—carpeted, shelves with blocks and puzzles, a couch the color of clouds. Grace held a stuffed elephant and stared with the concentration only toddlers can muster. Rachel sat cross-legged on the floor and made her voice the right size for the room. “Hi, Grace. I’m Rachel.” They colored. They stacked blocks. Grace knocked the blocks down and laughed quietly at the predictability of physics. On the second visit, Grace sat closer. On the third, she said “book” and handed one to Rachel.

The placement happened without drama. Paperwork continued behind the scenes, as it always does. Rachel kept expecting to feel unworthy or scared or like she was borrowing someone else’s life. Instead, she felt the opposite of betrayal: the rightness that arrives when promises are kept without speeches.

Grace came home on a Saturday that behaved like a blessing. Rachel made pancakes because she had always imagined pancakes would be part of this. Grace held the whisk with a seriousness that deserved a diploma. They ate at the small kitchen table. Grace dropped a blueberry and looked at Rachel to see if she would be punished. She wasn’t. She learned the house’s rules in the clean way children learn rules when adults write them in kindness.

Rachel learned a new choreography: backpacks and bedtime stories and pediatrician visits in offices that smelled less like hospitals and more like stickers. She learned that three-year-olds can teach you timetables of patience. She learned that love arrives, not as an epiphany, but as a number of small decisions concluded in the direction of someone else’s good.

On the anniversary of the surgery, Rachel drove to the county hospital with a note in her bag. She left it at the nurses’ station with a box of coffee and a dozen donuts because gratitude benefits from carbohydrates. The note read: Thank you for saving my life. Thank you for rescuing my future. I’m using it. She did not sign it with her last name. She didn’t need to.

She visited Dr. Wright for her scheduled follow-up, and they tried to talk about mundane things, then surrendered to the fact that ordinary conversation in that room carried different weight.

“Everything looks stable,” he said, after reviewing the latest scans. “We’ll push the next appointment to a year unless anything changes.”

“Okay,” she said. Then, because it felt necessary, “You were the first person who listened.”

He shook his head once, a gesture that meant the compliment made him uncomfortable, which was why he deserved it. “You were the first person who insisted,” he said. “You saved your life.” It wasn’t entirely true. It was true enough.

On the way home, she took a different route and passed the clinic where Andrew had built one life on top of another. The windows were dark. A For Lease sign hung in the glass in a font designed to be impersonal. Rachel felt nothing particular—no triumph, no fresh grief. Just accuracy.

In time, Andrew appealed. Appeals do what they do: they move through courts built to consider an argument even when the argument doesn’t deserve to win. The sentence held. The license did not return. The bar upheld its revocation. The paper trail endured, every signature a nail.

Emily sent a postcard at Christmas with a picture of Noah and Lily in front of a tree that had more meaning than decoration. On the back, she wrote: I’m in a support group. We’re okay. I tell them the truth. Thank you for not hating me. Rachel put it on the fridge with a magnet shaped like a saguaro.

Phoenix kept offering its light. Grace turned four. They ate cake on the couch because it felt luxurious. Rachel read to her each night and listened to the way a child repeats a new word because it feels like velocity. On some evenings, after Grace went to sleep, Rachel stood at the window and looked out at a city that had held her while she broke and held her while she rebuilt.

Her therapist asked what she would say to the version of herself who lay on an exam table staring at ceiling tiles while a probe stilled. “I’d tell her she isn’t crazy,” Rachel said. “I’d tell her that whisper she’s been ignoring isn’t a fear. It’s a fact. And I’d tell her that the exit is through the door that looks the most frightening because it leads to a room where people will tell the truth.”

The therapist nodded. “And what would you tell her about love?”

“That it isn’t a credential,” Rachel said. “And it isn’t a license. It’s a practice. If someone uses it to take your name out of the consent form, it isn’t love. It’s theft.”

In the second year, Rachel began volunteering with a patient advocacy group at the county hospital. She sat in rooms with women who had been spoken over and helped them prepare questions to ask the next doctor. She told them what questions had saved her life: What tests? What scans? What is the worst-case scenario we are trying to rule out? What happens if we wait? Who else should I see?

She never mentioned Andrew’s name in those rooms. Stories don’t always need proper nouns to be useful. She spoke in principles. She watched women write them down and saw posture change into insistence. She recognized the look in their eyes when they realized they were allowed to ask for evidence.

One Saturday, after an advocacy training, Rachel and Grace stopped at a park with a fountain that pretended to be a river. Grace splashed; Rachel watched. A woman sat on the bench beside her and said, with no preamble, “Are you Rachel Monroe?”

Rachel turned. The woman’s face carried the fatigue of someone raising children and the relief of someone who had made a difficult choice. “I am,” Rachel said.

“I just wanted to say thank you,” the woman said. “I saw your testimony on the news. I went to a second doctor. It wasn’t what you had, but it was something. It got caught. I have a daughter. I plan to be here for her.” She stood before tears made the conversation heavier than it needed to be and walked back to the playground with a lightness she’d earned.

Rachel told the story to her therapist, who smiled in a way therapists reserve for wins that can’t be posted on a bulletin board. She wrote it down later, too, in the notebook where she had kept dates and names in the early days, and which now held birthdays and the titles of children’s books that had been read so often the edges had softened.

On Grace’s fifth birthday, they baked a cake in the shape of an elephant. It sagged in the middle. They frosted it anyway. They invited neighbors who had become family through proximity and care. Someone brought a salad that was all wrong and exactly right because it was made by a person who wanted to help. Children ran in loops that obeyed none of the rules of physics and all of the rules of joy.

After everyone left, Rachel washed plates and listened to the quiet the way one listens to a piece of music you’ve loved long enough to notice new notes. She thought of the courtroom and the county hospital and the exam room and the folder named Forever Now and the device in the evidence locker and the way light falls on Phoenix at five in the afternoon in late spring.

If there is a moral, it is not that justice feels like salvation. It’s that truth is work, and sometimes the work pays. It’s that some men use access like a tool and some use it like a weapon; the difference is not subtle when you’re on the table. It’s that trusting your voice is not a betrayal of love. It is the only way to honor it.

Years later, when Grace would ask where she came from, Rachel would tell her the version of the story that belongs to children: that a room full of adults decided they belonged together and a judge agreed and a woman named Brenda had a smile that made paperwork feel like a holiday. When Grace would ask why she had no daddy, Rachel would say that their family is complete exactly as it is and that love makes families in more ways than one. When Grace would ask about scars—because children are observant in ways adults forget—Rachel would tell her a true thing that doesn’t harm: that doctors sometimes fix what hurts and sometimes good doctors fix what bad doctors broke.

Rachel does not keep the clear container in her house. It lives in evidence, and then it will live wherever destroyed evidence goes. She keeps instead a photo of Grace with a book in her lap, and a postcard from Emily that says she’s in school now, studying nursing, because she wants to be the kind of person who stands in the right room at the right time and says, “We need to read the consent form again.”

On certain mornings, when the desert light is gentle but the heat is honest, Rachel sits with coffee and writes the four sentences that became her life’s architecture on the inside cover of a new notebook, because repetition is how we turn truths into habits:

Listen to the voice that says something is wrong.

Ask for the test.

Read the page everyone skips.

Choose the door that leads to a room with witnesses.

She taught those sentences to the women at the advocacy group; she tucked them between the pages of intake packets like a blessing. She taught them to Grace in a version that fits a child: Use your words. Ask your questions. Read what you’re given. Choose the safe adult.

Phoenix keeps its promises: long light, evenings that smell like citrus, streets that learn your routine and say hello. Rachel’s life is smaller than the magazine version she once thought she wanted. It is infinitely larger than the room where she once lay still as a machine translated her body into gray. It contains a little girl who runs into her arms yelling “Mom!” It contains a circle of women who call her when they need a second opinion and a kind voice to say, “You’re not being dramatic. You’re being alive.”

It contains the one thing the past tried hardest to take away: the authority to say, in every room, “This body is mine.”

News

“We heard you bought a luxury villa in the Alps. We came to live with you and make peace,” my daughter-in-law declared at my door, pushing her luggage inside. I didn’t block them. But when they walked into the main hall…

The stems made my fingers cold. Wild lupines and Alpine daisies stood obedient in the chipped mason jar. I tilted…

In the morning, my wife texted me “Plans changed – you’re not coming on the cruise. My daughter wants her real dad.” By noon, I canceled the payments, sold the house and left town. When they came back…

The French press timer beeped. Four minutes. Caleb Morrison poured coffee into a chipped mug, watching the dark spiral fold…

My younger brother texted in the group: “Don’t come to the weekend barbecue. My new wife says you’ll make the whole party stink.” My parents spammed likes. I just replied, “Understood.” The next morning, when my brother and his wife walked into my office and saw me… she screamed, because…

My phone buzzed on the edge of a glass desk that reflected the Seattle skyline like a silver river. One…

My sister “borrowed” my 15-year-old daughter’s brand-new car, crashed it into a tree, and then called the police to blame the child. My parents lied to the authorities to protect their “golden” daughter. I kept quiet and did what I had to do. Three days later, their faces went pale when…

The doorbell didn’t ring so much as wince. One chime. A second. Then a knock—hard enough to make the night…

While shopping at the supermarket, my 8-year-old daughter gripped my hand tightly and, panicked, said, “Mom, hurry, let’s go to the restroom!” Inside the stall, she whispered, “Don’t move, look!” I bent down and was frozen with horror. I didn’t cry. I made a phone call. Three hours later, my mother-in-law turned pale because…

My daughter’s whisper was thinner than air. “Mom. Quickly. Bathroom.” We were at a mall outside Columbus, Ohio, halfway through…

My parents spent $12,700 on my credit card for my sister’s “luxury cruise trip.” My mom laughed, “It’s not like you ever travel anyway!” I just said, “Enjoy your trip.” While they were away, I sold my house where they were living in for free. When they got ‘home’… my phone 29 missed calls.

My mother’s laughter hit like broken glass through a cheap speaker. Sharp. Bright. Careless. “It’s not like you ever travel…

End of content

No more pages to load