The receipt that blew up my life cost $4.50 and came from a café I was absolutely sure I had never stepped foot in.

I found it on a Saturday morning in Phoenix, Arizona, sunlight frying the side of my apartment building like the world’s biggest heat lamp. The AC rattled in the window. My girlfriend’s half of the bed was still neatly made because she was in Chicago at a conference, texting me photos of deep-dish pizza and Lake Michigan.

I was alone, bored, and procrastinating on the article my editor at Buzzstream had asked for: Ten Celebrity Selfies That Broke the Internet. So instead of writing, I decided to do the most thrilling thing a 38-year-old man in Phoenix can do on a weekend.

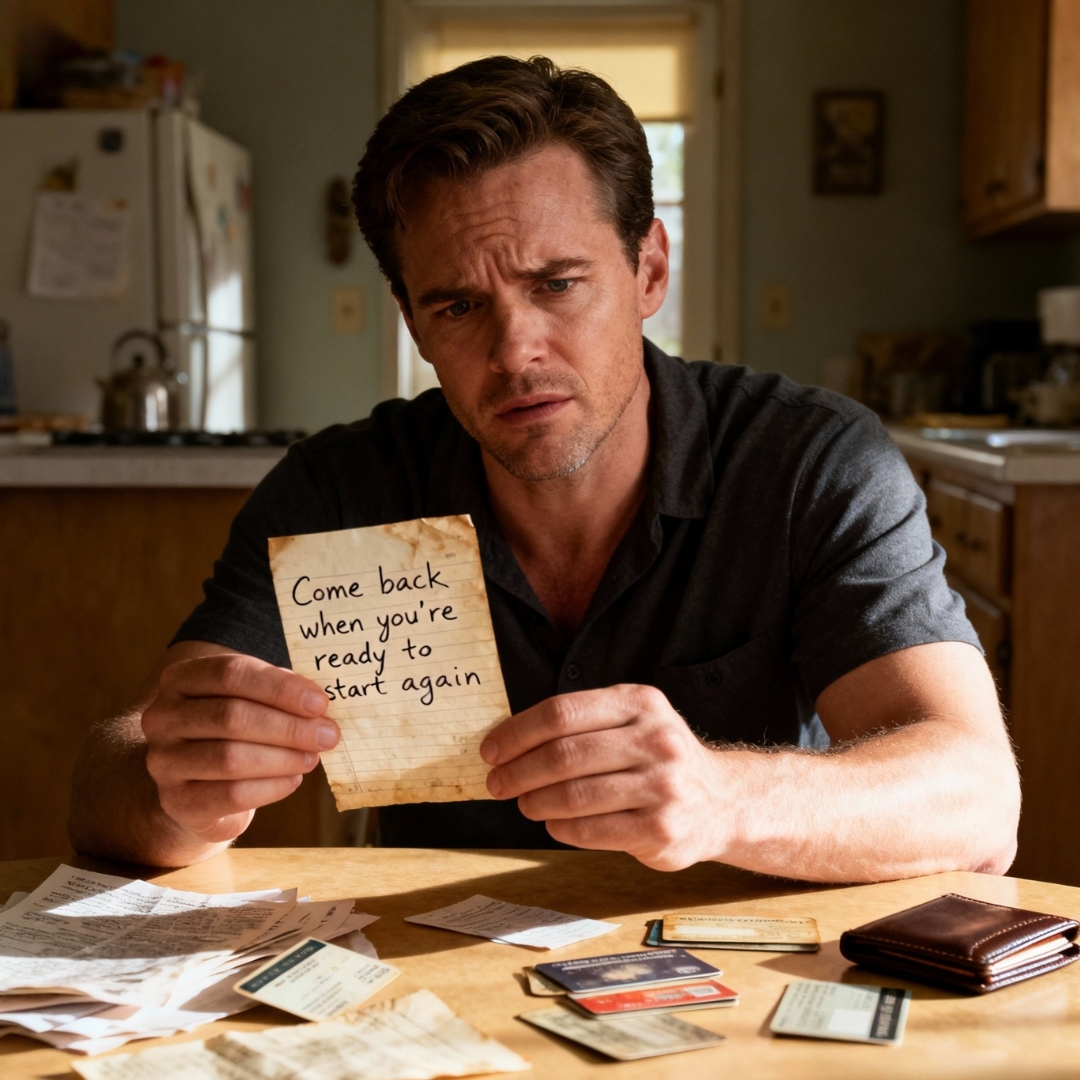

I cleaned out my wallet.

I sat at my tiny kitchen table, dumped the contents onto the surface, and started sorting through my life in miniature: cracked loyalty cards from coffee chains, a driver’s license with a photo I hated, expired insurance cards, folded receipts from the grocery store, business cards from people I couldn’t remember meeting.

Most of it went straight into the trash.

Then I saw it.

A narrow, crumpled strip of thermal paper, softer than the others from being handled more. The logo at the top read:

THE SECOND CUP

Phoenix, AZ 85018

Date: September 14

Time: 10:42 AM

Total: $4.50

Paid: Cash

I frowned.

I remembered the name of every café within a five-mile radius of my apartment and my office in downtown Phoenix. There was no Second Cup on that mental map.

I turned the receipt over.

On the back, in looping, careful handwriting that definitely wasn’t mine, someone had written:

Come back when you’re ready to start over.

The words landed in my chest like a fist.

I stared at them for a long time. The late-morning light moved across the table, turning the paper almost translucent. The AC hummed. A neighbor’s truck started outside.

I had never been to this café. I would’ve remembered.

But someone out there—not my bank, not my landlord, not my editor—believed there was a version of me that might one day be “ready to start over.”

I wasn’t ready for anything.

Officially, I was fine.

I had a job at a digital media company in downtown Phoenix, a place called Buzzstream that paid me $68,000 a year to write headline bait for people scrolling on their phones in Target parking lots. You Won’t Believe What This Celebrity Did at Coachella. This One Food Is Destroying Your Sleep, According to Science. Doctors Hate Her For This One Simple Trick.

Garbage. I wrote it. I knew it was garbage.

But it paid for rent and takeout and the occasional weekend in Sedona when my girlfriend, Mae, needed red rocks and expensive smoothies to reset her nervous system.

Fifteen years earlier, I’d graduated from journalism school with a head full of names: Woodward, Bernstein, Baldwin, Didion. I wanted to write stories that outlived the news cycle, the kind of investigative pieces that toppled corrupt city councils and forced powerful people to answer uncomfortable questions. I wanted to move to New York or D.C., work for a national outlet, sit in newsrooms filled with bad coffee and better questions.

Instead, I got Buzzstream.

Things in the real world hadn’t gone the way my professors said they would. Nobody wanted to pay for local investigative work. “Print is dying,” everyone kept saying in those early years, like we were standing around a hospital bed watching an old relative wheeze. After a year of stringing for small sites and eating more instant ramen than is medically recommended, I took the steady paycheck.

I told myself it was temporary.

Then a year became three. Then five. Then fifteen.

The part of me that cared about journalism—like really cared, the way you care about someone you stay up talking to until sunrise—had gone quiet. Numb. Like someone left it outside in the Phoenix sun until it dried out and cracked.

I was “fine.”

Except there I was, holding a slip of paper from a café I didn’t remember, trying not to see myself in the sentence when you’re ready to start over.

Curiosity, more than courage, made me reach for my phone.

I typed “The Second Cup Phoenix AZ” into Google Maps.

A pin popped up in Arcadia, about twenty minutes east of my apartment: a strip of small, locally owned places wedged between a yoga studio and a bike repair shop. The satellite image looked like every other low-slung building in this city: sun-bleached parking lot, a few trees fighting for their lives, off-white stucco.

I should’ve tossed the receipt. Chalked it up to a mix-up—a piece of someone else’s day that had migrated into my wallet.

Instead, I grabbed my keys.

“You’re being ridiculous,” I told myself as I drove east on the 202, the air inside the car artificially cold while the desert outside shimmered. “You’re driving across town because of a piece of paper.”

But my foot stayed on the gas.

Arcadia was one of those neighborhoods that made you forget you were in a sun-scorched sprawl. Tree-lined streets, older ranch houses with updated kitchens, kids on bikes, people walking their dogs as if the asphalt wasn’t hot enough to fry eggs.

The Second Cup sat in a row of small businesses: a consignment boutique, a barber shop with an old-school swirl pole, a Pilates studio with a name that sounded like an essential oil. From the outside, it looked like nothing special: hand-painted sign, potted plant by the door, chalkboard propped on the sidewalk listing daily specials in loopy handwriting.

I almost turned the car around.

Instead, I parked, sat with my hands on the steering wheel for a full minute, then got out and went inside.

A bell over the door chimed—not the sharp, electronic kind, but a real bell with a soft ring.

The inside was… calm. Warm. Worn wood floors. Ten, maybe twelve small tables, all mismatched but arranged like they belonged together. Local art on the walls: desert landscapes, portraits, abstract shapes in sunset colors. Someone had strung fairy lights along one corner of the ceiling. Plants sat in terracotta pots on the window ledges, leaves glossy and alive.

It smelled like real coffee and fresh bread, not like syrup and burnt beans.

Soft jazz played from speakers I couldn’t see. The noise level was low—murmured conversations, the hiss of steam, the clink of ceramic on ceramic.

Behind the counter, a woman in her sixties wiped down the espresso machine. Her gray hair was pulled back in a loose bun, strands escaping around a face lined in the way that meant she’d done more laughing than frowning. She wore a plain black T-shirt, jeans, and a necklace with a small silver spoon pendant.

She looked up when she heard the bell.

And smiled.

Not the tight, customer-service smile I’d seen all over downtown. A real smile that landed in her eyes.

“I was wondering when you’d come,” she said.

I stopped where I was.

“What?”

She gestured toward the menu board above her head. “You’re here for coffee, I assume. What can I get you?”

“I’ve never been here before,” I said automatically.

“I know,” she said. “But I’ve been expecting you.”

She said it like a fact. Like she was pointing out the weather.

“I—uh—” I pulled the receipt from my pocket where I’d shoved it like evidence. “I found this in my wallet. I don’t know how it got there.”

I held it up.

She wiped her hands on a towel, took the paper from me, turned it over.

A flicker of recognition crossed her face.

“That’s my handwriting,” she said, then handed it back. “I wrote that about six months ago.”

“But I’ve never been here.”

“I didn’t say you had,” she replied. “Only that I wrote it.”

“Then how did it end up in my wallet?”

She tilted her head. “Does it matter? You’re here now. That’s the important part.”

That maddened me and soothed me at the same time.

“My name’s June,” she added, like that explained anything. “Welcome to The Second Cup.”

I stared at her, at the tidy row of cups behind her, at the chalkboard listing flavors, at the window where the Arizona sun poured in golden light that somehow didn’t feel harsh in this space.

“I—uh—coffee, I guess,” I said. “Black.”

“Black,” she repeated. “Solid choice. Have a seat anywhere. I’ll bring it out.”

There were a few people scattered around: an older man in a button-up shirt reading The Arizona Republic with an actual paper rustle, a woman in leggings working on a laptop, a teenager with earbuds drawing in a sketchbook. They looked relaxed. Focused. Like they belonged there.

I chose a small table by the window. The wood was scarred in places, rings from old cups, someone’s initials carved in one corner.

O + ?

I sat, receipt in hand, feeling like I’d walked into the middle of a conversation the room was having with itself.

June brought the coffee a few minutes later on a chipped saucer, along with a blueberry muffin on a small plate.

“I didn’t order that,” I said.

She shrugged. “On the house. You look like you could use something sweet.”

“I—thank you.” I waited. She didn’t leave. Instead, she sat down across from me, folding her hands on the table like we’d done this a hundred times.

“I’m really confused,” I said. “Can you tell me what’s going on? Why did you write that? And how did this—” I tapped the receipt. “—get to me?”

She didn’t answer right away. She looked at me. Really looked. Not in that quick, assessing way people do in elevators, but with a patience that made me want to fidget.

“It has come to my attention,” she said eventually, “that you’re lost.”

I laughed, sharp. “What, like spiritually? Geographically I think I’m okay.”

“Not physically lost,” she said. “Lost in that you’ve forgotten who you were supposed to be.”

I snorted. “And who was I supposed to be?”

“That’s for you to remember,” she said calmly. “Not me. I only run the coffee shop.”

“Only,” I muttered. “You wrote a prophetic message on a receipt that somehow landed in my wallet. That’s not exactly standard barista behavior.”

“I knew the only person who could help you was you,” she continued, as if I hadn’t spoken. “But sometimes people like you need a nudge. A small invitation to walk through a different door. So I wrote that message. And waited.”

“For… me?” I asked, skeptical but unable to look away.

“For whoever needed it,” she said. “But yes, I had a hunch about you.”

“How? You didn’t even know me.”

“Don’t worry about the how yet,” she said, smiling. “We’ll get there. Drink your coffee.”

I lifted the mug out of sheer obedience.

The coffee was… good. Not just in a “this isn’t terrible” way. It was smooth, with that chocolatey depth I’d only ever found in certain Portland cafés I’d visited once for a story that never got written. It tasted like someone had paid attention.

“What do you do, Oliver?” she asked.

The sound of my name in her mouth made my hand jerk. Coffee sloshed.

“How do you know my name?” I demanded.

She shrugged. “It’s written all over you. You look like an Oliver.”

“That’s not… that’s not how names work.”

She just smiled.

“What do you do?” she repeated.

“I—uh—I’m a journalist,” I said out of habit.

The word felt false in my mouth. Heavy. Costumed.

“Are you?” she asked.

“I mean, technically. I work for Buzzstream.”

Her brow furrowed. “Is that one of those sites where every headline sounds like a dare?”

“Yes.”

“And you like that?” she asked.

“I like paying my rent,” I said. “I like not eating ramen three nights a week. I like not pitching editors in New York who don’t know my name.”

“That’s not what I asked.”

No one had spoken to me like this in years. Maybe ever. Even my therapist (back in my brief attempt at therapy) had stayed firmly in the realm of “how does that make you feel?” June was going straight for the jugular.

“I don’t hate it,” I lied.

“You hate it,” she corrected. “You hate it and you’ve decided that hating it is the price of staying alive.”

“You’re very blunt for someone who sells muffins.”

She laughed—a quick, delighted sound. “People don’t come here just for muffins.”

“Then why do they come?” I asked, glancing around the room.

“To remember,” she said. “Usually, something about themselves.”

“That’s a very poetic way of saying you run a coffee shop.”

“You want people to read your work and remember things about themselves,” she countered. “Do you tell them you type words on a screen for clicks?”

I flinched.

She softened. “Drink your coffee,” she said. “Come back tomorrow. Or don’t. That’s your choice. But if you do come back, maybe bring your real self with you next time.”

I left half an hour later, bleary and unsettled. The receipt burned in my pocket.

In the parking lot, the Arizona sun hit me full force. The air felt like opening an oven. The Second Cup’s bell still echoed in my ears.

By the time I’d driven back across town, the whole thing felt like a dream. The café, June, the certainty in her eyes when she’d said the word lost.

My phone buzzed when I walked into my apartment. A photo from Mae: a shot of the Chicago River glittering under a cloudy sky, her face half in the frame, smiling.

Panel went well, she texted. Miss you.

I texted back Miss you too and didn’t mention the receipt, the café, or the woman who’d looked at me like she knew the blueprints to my life.

On Monday, I went back to being “fine.”

I rode the elevator up to the Buzzstream office with the same herd of tired millennials and Gen Xers in Phoenix office casual: jeans and polos, dresses and cardigans, tired eyes and steel coffee tumblers. The building was all glass and light and free LaCroix, the kind of open-plan space someone in San Francisco had designed after seeing an article about “collaborative work environments.”

Mae and I met in that elevator three years earlier. She was holding a container with overnight oats, wearing navy scrubs and white sneakers. She worked one floor down as a nutritionist in a medical practice that rented office space from Buzzstream’s landlord. She’d smiled at me and pointed at my press badge.

“Real journalist?” she’d asked.

“Depends on who you ask,” I’d answered.

She’d laughed. We’d been talking ever since.

On Monday night, she got back from Chicago and met me in the lobby.

Her dark hair was pulled into a messy ponytail. A lanyard from the conference hung from her neck. She smelled like hotel soap and airplane air.

“How was work?” she asked once we were in the elevator, a soft kiss brushing my cheek.

“Same as always,” I said, pressing the button for my floor.

She studied my face. “You look tired.”

“I am tired.”

“Are you happy there?” she asked quietly.

I gave the answer I always gave.

“I’m fine.”

But my mind was still back in Arcadia, in a small café where a stranger had looked at my life and said, “You’re lost.”

I went back to The Second Cup three days later.

I told myself it was about the coffee. About curiosity. About needing a change from the over-air-conditioned Starbucks near the office.

In reality, it was like being pulled by something I couldn’t name.

When I walked in, the bell chimed and June looked up from the pastry case.

“Oliver,” she said, like my name was a relief. “Good to see you.”

“Hi,” I said. “Uh… black coffee?”

“The usual.” She winked. “You’re officially a regular.”

“I’ve been here once.”

“Once is enough to start a pattern.”

I sat at the same table by the window. My phone buzzed with a Slack notification from my editor: Need that Kardashian piece by 3 pm, pls and thx. I turned the screen over.

June brought the coffee and—again—sat down without asking if the seat was taken.

“How’s work?” she asked.

“Busy,” I said.

She waited.

“Garbage,” I corrected myself. “It’s garbage and I’m good at it and that makes it worse.”

“Tell me,” she said. Not like a command. Like an invitation.

And this time, maybe because I’d spent the past three days thinking about how unspecial my clickbait headlines really were, I did.

I told her about Buzzstream: the way our entire business model was built around tricking people into clicking on things they didn’t really care about; the way we measured success in page views and ad impressions and minutes spent scrolling, not in whether anyone learned anything; the way our Slack channel lit up whenever a story “performed,” as if we’d done something noble instead of just capitalizing on someone else’s divorce, meltdown, or bad outfit.

I told her how I’d started out writing obits for a small paper in Texas, then moved to Phoenix for a local news site that got bought out, then folded, then morphed into Buzzstream.

“Investigative work doesn’t pay,” I said. “Or when it does, it pays two people in New York and one guy in D.C. Everyone else writes listicles to keep the lights on.”

“Do you still want to do it?” she asked.

“Yes,” I said, and the word shocked me with its honesty. “But I think I forgot how. Or I convinced myself I wasn’t good enough to make it.”

“You are good enough,” she said. “You’ve just been using your skills in the wrong direction.”

“Do you always talk like a guidance counselor?”

“Only to people who need guidance,” she said lightly.

“And what, this place is your office?”

She glanced around the café. “Sometimes people come in because they like the muffins. Sometimes because they like the quiet. Sometimes because they’ve spent fifteen years telling themselves their life has to be what it is, and they’re lying.”

I stared into my coffee.

“I can’t just quit my job,” I said. “I’ve done hungry. It sucked. I’m not twenty-three anymore. My knees can feel the weather.”

“I didn’t tell you to quit your job,” she said. “I said you’ve forgotten who you were supposed to be. Those aren’t the same thing.”

“Feels like it.”

“The question isn’t ‘what are you going to do?’” she said. “The question is ‘what do you want?’”

A cliche, sure. But she said it without any Instagram quote energy. Just… quiet.

“If nothing were stopping you,” she continued, “no rent, no student loans, no fear, no cranky editors in New York—what would you do?”

I didn’t even have to think.

“I’d write stories that matter,” I said, the words rushing out like I’d been holding my breath for a decade. “Long ones. Messy ones. Pieces about people who aren’t famous but are doing something important. I’d spend weeks on a story instead of half an hour. I’d actually care if it was true instead of if it got ten thousand shares.”

Her eyes warmed. “Good. There it is.”

“There what is?”

“The thing you forgot,” she said. “Now that you’ve said it out loud, you can’t un-know it. That’s the annoying part.”

“So now what? I’ve said it. The universe heard me. Do I get struck by lightning or offered a job at The New York Times?”

She laughed. “No lightning. No immediate job offers. Just coffee. And work.”

She tapped the table between us.

“Start,” she said. “Write one story that matters. Not for Buzzstream. For you. For whoever needs to read it. Do it after work. Do it here. Do it with fear chewing on your ankles. Just do it.”

“And then?”

“Then see what happens.”

I thought of all the reasons this was ridiculous. All the metrics and job listings and statistics about dying media. All the nights I’d lain awake wondering how I’d pay rent if Buzzstream ever figured out that an algorithm could do 60% of my job.

“Will there be muffins?” I asked.

“Absolutely,” she said.

So I came back the next day.

And the next.

And the next.

Mae started noticing I was “working late” more often.

“What are you doing after work?” she asked one evening, curled up on my couch in leggings and a faded Arizona State sweatshirt, laptop balanced on her knees as she added notes to a patient’s file.

“Writing,” I said.

“For Buzzstream?”

“Not exactly.”

Her eyes lit. “For you?”

“Maybe.”

She sat up. “Do you want to tell me?”

“Not yet,” I said, and her face fell for a second before she covered it.

“Okay,” she said. “When you’re ready.”

I hadn’t told her about The Second Cup yet. About June. About the looping handwriting that had set something in motion I couldn’t quite name.

It felt too fragile, like a balloon I’d just started to inflate. I didn’t want to open my mouth too wide and accidentally let all the air out.

At the café, I claimed the same table by the window every afternoon. June would wordlessly set a mug of black coffee next to my laptop. Some days she brought a muffin. Some days she brought nothing but a nod.

Other days, she sat and asked infuriating questions.

“Who’s your first story about?” she asked one Wednesday.

“Her name’s Rosa,” I said. “She runs a housing nonprofit in South Phoenix. She’s been fighting for affordable housing for twenty years.”

“Why her?” June asked.

“Because she cares,” I said. “Because she’s tired. Because she’s had the city council speak over her for decades and she keeps showing up anyway. Because she’s the opposite of everything I’ve been writing for the past fifteen years.”

“There’s your lede,” June said. “Not literally. But you know what I mean.”

I interviewed Rosa in her small office off Baseline Road, a whiteboard behind her covered in numbers and dates and names of neighborhoods. I followed her to a council meeting where she sat in the back and took notes while three men in suits tried to pretend they didn’t see her. I talked to the people we met on her rounds—grandmothers, single dads, kids playing in courtyards surrounded by peeling paint.

I wrote in The Second Cup. I wrote late at night at my kitchen table. I wrote in the mornings before Buzzstream.

I wrote badly at first. Rusty. Too flowery, then too clipped. I’d forgotten how to care about transitions, about pacing, about how to end a paragraph in a way that made you keep reading.

But under the flab, I could feel something waking up. A muscle memory.

“You’re getting there,” June said after reading a second draft. “You’ve stopped writing like you’re trying to trick someone.”

“I literally am trying to get them to keep reading,” I said.

“That’s not a trick,” she countered. “That’s a promise. If you keep reading, I’ll tell you the truth. That’s the deal.”

I finished the piece on a Sunday afternoon, the sky outside my apartment streaked with the kind of gold that makes even gas stations look cinematic.

Four thousand words.

Facts checked. Quotes solid. My voice, somewhere in the middle of it all—not shouting, not whispering. Just… steady.

I stared at it, heart pounding, and realized I’d forgotten to breathe.

Later that night, sitting on Mae’s couch, I handed her my laptop.

“What’s this?” she asked.

“Something I wrote,” I said. “Not for work. For me.”

She curled her legs under her, opened the document, and started reading.

I watched her face instead of the screen. Watched her eyes move, her brow furrow, her mouth curve, her fingers tighten on the edge of the laptop. When she finished, she wiped at her eyes with the heel of her palm.

“Oliver,” she said softly. “This is… beautiful.”

“You think so?”

“I know so.” She turned the laptop toward me and tapped the screen. “This. This is you. This is the person I met in that elevator who used to get mad about city budgets and zoning laws and food deserts.”

“I thought that guy died,” I said lightly.

She squeezed my hand. “He didn’t die. He just got tired.”

“I don’t know what to do with it,” I admitted. “I wrote it for myself. To prove I could still… do that.”

“You pitch it,” she said immediately. “Not to Buzzstream. To someplace that deserves you. Mother Jones. ProPublica. That social justice magazine you read that keeps asking for pitches.”

“That’s adorable,” I said. “You think editors just wait around for guys in Phoenix to send them long pieces about local housing issues.”

“Maybe they do,” she said. “Maybe they don’t. But you’ll never know if you don’t send it.”

I did.

Not to The New York Times. Not yet.

To a mid-sized online magazine based in California that focused on social justice issues around the U.S. I wrote an email that wasn’t cool or charming. Just honest.

My name is Oliver. I’ve been writing click-driven content for too long. I wrote this because I needed to remember why I became a journalist. If you think your readers would care about housing in Phoenix, I’d be honored if you’d consider it.

I hit send.

And waited.

They replied in two days.

We love this. We’d like to publish it. Rate is $500. Are you open to light edits?

I had to read the email three times to believe it.

June was polishing mugs when I rushed into The Second Cup, my laptop bag thumping against my hip.

“They want it,” I said, breathless, as if she’d been following the whole thing like a sports game.

She didn’t ask who “they” were. She just smiled and set a mug in front of me.

“Of course they do,” she said. “You told the truth. People are starving for that.”

The piece went live the following week.

Rosa’s face at the top. My name under the headline in simple black text. No exclamation points. No ALL CAPS. No “You Won’t Believe…”

Just: The Woman Who Refused to Let Phoenix Forget Its Housing Crisis.

People read it.

Not millions. But enough.

They shared it. “This opened my eyes,” one comment said. “I had no idea,” another wrote. A local podcast asked to interview me. A city council member emailed Rosa asking to meet. Donations to her nonprofit ticked up.

More importantly—for me—it felt like something had unclogged inside my chest.

“You look different,” Mae said, sliding her hand into mine in the elevator one evening.

“Older?” I joked.

“Lighter,” she said. “Like you’re not carrying a secret you hate.”

“I still have the Buzzstream stuff,” I pointed out. “Tomorrow I have to write about a reality TV star’s haircut.”

“But now you know you’re not stuck there forever,” she said. “There’s a difference.”

She was right.

A few weeks later, I finally asked June the question that had been nagging at me since day one.

“How did that receipt get into my wallet?” I asked. “Really. No more fortune-teller answers.”

She wiped down the counter, the damp towel making small arcs.

“Are you sure you want to know?” she said.

“Yes. Absolutely.”

“All right,” she said. “You remember I said I’d been expecting you?”

“Yes,” I said.

“Your girlfriend,” she said calmly. “Mae.”

My stomach dropped.

“She came in here about seven months ago,” June continued. “She was on her way back from a doctor’s appointment and stopped for coffee. We got to talking.”

Mae had a way of getting strangers to talk. That part didn’t surprise me.

“She told me about you,” June said. “About how smart you were, how funny, how passionate you used to be about the news. And about how you’d gotten… dimmer. How you’d started calling yourself ‘fine’ in a way that meant anything but.”

I swallowed around the tightness in my throat.

“She said she’d tried to nudge you,” June went on. “Send you job listings, share articles, remind you that you were capable of more. But you shrugged it all off. So I wrote that message on the back of a receipt and handed it to her. I told her to find a way to get it to you without making it a fight.”

“She slipped it into my wallet,” I whispered.

June nodded. “And trusted that you’d find it when you were ready.”

Six months ago. September. I tried to remember that day. I couldn’t. Just a blur of deadlines and headlines and commute.

“She could’ve just told me to come here,” I said.

“She could have,” June agreed. “Would you have listened?”

I thought about that. About how I’d bristled even at June’s gentle prodding. About how stubbornly I’d clung to “fine.”

“No,” I admitted. “I would’ve felt managed. Controlled.”

“Exactly,” she said. “She loves you, you know. Enough to let you think you found your way here on your own.”

I drove straight to Mae’s after I left The Second Cup that night.

She opened the door in leggings and an old ASU hoodie, hair in a messy bun. Netflix paused on her TV behind her.

“Hi,” she said, surprised. “Everything okay?”

“You gave June the receipt,” I blurted.

Her face went white. Then pink. Then something softer.

“She told you,” she said quietly.

“She said you came in months ago,” I said. “That you told her about me. That you asked for help.”

“I didn’t know if I should,” Mae said. “It felt sneaky. But I was watching you die inside, Oliver, and I couldn’t do nothing.”

“You think I was dying inside?” I asked.

“You smiled less,” she said. “Snapped more. You stopped talking about stories and started talking about clicks. Every time I asked if you were happy, you said ‘I’m fine’ in a voice that sounded like a locked door.”

I leaned my forehead against the doorframe.

“You could have just told me to go to the café,” I said weakly.

“You would’ve argued,” she said. “You would’ve told me you didn’t have time. That it was silly.”

“Probably,” I admitted.

“So I thought… if you found that note yourself,” she said, “maybe it would feel less like I was pushing you and more like… the universe was inviting you.”

“That’s manipulative,” I said.

“I know,” she said, wincing. “Good manipulative or bad?”

“Good,” I said, and pulled her into a hug so tight that she squeaked. “Very good.”

She laughed into my shoulder. “So it worked?”

“It worked,” I said. “I wrote a real story. People read it. An editor in California wants more. June says I’m not allowed to call myself a content goblin anymore.”

We stood in the doorway like that for a long moment, Phoenix sunset turning the hallway orange.

Later that night, after we’d microwaved leftovers and argued about whether to start a new show or rewatch an old one, I opened my laptop and started a new document.

Title: Second Chances.

“The receipt that changed my life cost $4.50…”

I stopped. That was too on the nose. Too meta.

I deleted it.

I started again.

This time, I wrote about June.

About how she’d taken her husband’s life insurance money ten years earlier after he died in a sudden highway accident on I-10 and bought a failing café on a quiet Phoenix street. How she’d renamed it The Second Cup because she liked the idea of a place people came when they needed another shot at something. How she watched people walk in off the street with grief in their shoulders and left with something a little lighter.

I wrote about Mario, who traded a six-figure job at a law firm in downtown Phoenix for a classroom full of bored teenagers in Glendale and never looked back. About Adriana, who had stopped painting for a decade after one cruel critique and had started again at a table by that window. About Lenny, who sat in the far corner now, practicing saying “I” instead of “we” after a twenty-two-year marriage ended.

I wrote about myself, too, in third person at first, as if that would make it less raw.

I pitched the idea to the same California editor: a series of long pieces about people starting over, anchored around an odd little café in Phoenix. Not glossy reinvention stories. Not makeover montages. Real, messy, ordinary attempts at beginning again when you’re closer to forty than twenty.

She emailed back within a day.

Yes. Absolutely yes. How many installments can you do?

Six, I wrote back, fingers trembling. Maybe more.

We settled on a rate that wouldn’t make me rich but would, if I was careful, keep me from eviction. Mae looked over the numbers with me at my kitchen table, her pen tapping against her bottom lip.

“If we cut back a little,” she said, circling a few overpriced line items in my budget (DoorDash, random gadgets from Amazon), “and if you’re okay not upgrading your phone for another year, we can make this work. I can help with groceries for a bit.”

“I can’t let you—” I started.

“You’re not letting me,” she said firmly. “I’m offering. We’re a team, remember?”

Quitting Buzzstream felt like jumping off a cliff with a parachute someone swore they packed correctly.

My editor was baffled.

“You’re leaving… to freelance?” he asked, as if I’d said I was leaving to join a traveling circus.

“Yes,” I said. “I want to focus on long-form.”

“Long-form doesn’t pay,” he said reflexively.

“I’ve started getting paid,” I countered. “Not a lot. Enough.”

“Well,” he said, leaning back in his ergonomic chair, “if you change your mind…”

“I won’t,” I said. For the first time in that building, my voice didn’t sound like an apology.

Walking out of the glass doors of the Buzzstream office building into the Phoenix heat that day, my laptop in my bag and my heart hammering in my throat, I felt… not free exactly.

More like honest.

The Second Chances series launched in October, just as the desert was remembering what it felt like to be less than scorching.

The first piece—June’s story—hit differently than my housing article. People wrote in from all over the U.S. “I needed this,” one comment said from a woman in Ohio. “I’m 52 and thought it was too late to change careers.” A teacher in New Jersey emailed that Mario’s story gave him courage to leave his bar exam dreams behind.

Other publications started to notice. An editor from a New York site asked if I’d consider writing about second-chance stories in other cities.

For the first time, my inbox was full of things I wanted to answer instead of press releases written in all caps.

The money wasn’t steady yet. Some months were tight. I took on corporate copywork between investigations. There were nights when I woke up at 3 a.m. panicked about health insurance.

But every morning that I walked into The Second Cup with my laptop and June slid a mug of coffee toward me with that “I knew you’d show up” look in her eyes, it felt worth it.

One chilly Saturday—you know, Arizona chilly, where it was 55 instead of 105—I walked into the café to find June reading a printed copy of my latest piece with reading glasses perched on the end of her nose.

She looked up as I sat down.

“You did it,” she said.

“Did what?” I asked.

“Started over,” she replied matter-of-factly. “I’d say we should throw you a party, but you don’t strike me as a balloon guy.”

“I prefer muffins,” I said. “And lower blood pressure.”

She laughed.

“What’s next?” she asked.

“I don’t know exactly,” I said. “More stories. Maybe a book about all of this. About people who didn’t get it right the first time.”

“That’s everyone,” she said.

“Exactly.”

Mae slid into the seat beside me a few minutes later, cheeks flushed from the walk from her apartment.

“Did you tell June?” she asked me.

“Tell me what?” June said, interest piqued.

Mae held up her hand.

A glint of light flashed off the simple silver band on her finger.

“We’re engaged,” she said.

My heart did that weird swell thing it had done when she’d first said she loved me in a Target parking lot two years earlier.

June stood, came around the table, and hugged us both in one bony-armed sweep that smelled like coffee and yeast.

“You two,” she said, shaking her head. “Conspirators. I should’ve known you were in it for the long haul.”

“You did know,” I said. “Pretty sure you wrote it on a receipt.”

We all laughed. The bell over the door chimed as someone else came in, the morning light spilling across the worn wood floor.

Sometimes, I still find scraps of my old life.

A Buzzstream headline will float across my social media feed. Former coworkers will post photos of the office Halloween party. I’ll see a headline so bad I’ll know exactly who wrote it.

Sometimes, my chest tightens. Not with envy. With that weird, numb nostalgia for a routine, even if it was killing you.

Then I remember sitting at my kitchen table that Saturday morning in Phoenix, holding a receipt that shouldn’t exist, turning it over and reading the words:

Come back when you’re ready to start over.

I wasn’t ready.

I came anyway.

And that made all the difference.

News

My husband threw me out after believing his daughter’s lies three weeks later he asked if I’d reflected-instead I handed him divorce papers his daughter lost it

The first thing that hit the driveway wasn’t my sweater. It was our anniversary photo—spinning through cold air like a…

He shouted on Instagram live: “I’m breaking up with her right now and kicking her out!” then, while streaming, he tried to change the locks on my apartment. I calmly said, “entertainment for your followers.” eventually, building security escorted him out while still live-streaming, and his 12,000 followers watched as they explained he wasn’t even on the lease…

A screwdriver screamed against my deadbolt like a dentist drill, and on the other side of my door my boyfriend…

After my father, a renowned doctor, passed away, my husband said, “my mom and I will be taking half of the $4 million inheritance, lol.” I couldn’t help but burst into laughter- because they had no idea what was coming…

A week after my father was buried, the scent of lilies still clinging to my coat, I stood in our…

“Get me a coffee and hang up my coat, sweetheart,” the Ceo snapped at me in the lobby. “This meeting is for executives only.” I nodded… And walked away in silence. 10 minutes later, I stepped onto the stage and said calmly, welcome to my company.

The coat hit my arms like a slap delivered in silk. Cashmere. Midnight navy. Heavy enough to feel expensive, careless…

My fiancé said, “I want to pause the engagement. I need time to think if you’re really the right choice.” I said, “take all the time you want.” he thought he was the one ending things. But the moment he opened his apartment door that evening… He realized something already ended hours before he made his decision.

The text came in like a feather, and somehow it still cut. Don’t wait up tonight. I’m out with Nate…

“Hope you like fire,” my son-in-law whispered, locking me in the burning cabin while my daughter smiled coldly. They thought my $5 billion fortune was finally theirs. But when they returned home to celebrate, they found me sitting there… With a shock of a lifetime…

The first thing I saw was Brian’s smile—thin as a razor, lit by the cabin’s firelight—right before the door clicked…

End of content

No more pages to load