The garage smelled like motor oil and old cardboard—the kind of ordinary, harmless smell that makes you believe your life is still yours.

I remember gripping the neck of a cheap bottle of pinot grigio like it was proof I belonged there, like it was a peace offering, like it was normal to turn thirty in your parents’ kitchen in a quiet American suburb where people mow their lawns in silence and wave like nothing bad ever happens behind closed doors.

I was in a good mood that day. Almost embarrassing how good.

I’d just finished a big project at work, the kind that makes your boss nod at you like you’re finally becoming someone. I’d been thinking, Thirty is going to be my year. Not in a cliché way—more like a private promise. A clean decade. A reset. A little less chaos, a little more control. I had a mental list: start a 401(k) I actually understand, drink more water, stop dating men who “aren’t ready,” finally buy a real couch instead of something that looks like it belongs in a college rental.

I turned onto my parents’ street and saw all the cars.

Not just a few.

A lot.

Every curb like a crowded airport pickup lane. SUVs, sedans, a dusty minivan that looked like it had been driven cross-country. I remember my stomach dropping, but not because I thought, Surprise party.

My parents weren’t party people. They were stiff drink-after-work-in-silence people. The kind of couple who considered “hosting” to be a mild medical emergency.

So my brain went where it always went with them: fear.

I actually felt that fight-or-flight jolt—adrenaline like cold soda in my veins—thinking maybe my dad’s blood pressure finally did what it threatened to do every Thanksgiving. Maybe someone collapsed. Maybe the neighbors found him on the driveway.

I pulled into the garage, heart knocking. The garage felt safe. It felt like childhood. The same old shelving, the same paint cans, the same smell. I stepped out, clutching the wine, and for a split second I thought: I’m being dramatic. It’s probably nothing. Maybe it’s a church thing. Maybe Mom finally got persuaded into some neighborhood gathering.

Then I opened the door to the kitchen.

And it was like walking into a wall of refrigerated air.

Seventy-five people.

That number still feels unreal because it wasn’t a normal crowd. It wasn’t people laughing and moving and cheering. It was a set. A staged audience. Humans arranged with intention.

My aunt Sarah from Oregon—who hates flying—was there, standing stiff like she’d been placed by a director. My cousins. Neighbors from three houses down. My mom’s book club women, wearing the same bright lipstick they always wore to pretend they were still having fun. My dad’s co-workers from the county office. People I hadn’t seen in years.

They weren’t smiling.

They weren’t cheering.

They were stationed.

That’s the only word that fits.

Stationed—like an honor guard. Like witnesses. Like they’d been instructed to keep their faces neutral so the moment could land cleanly.

I stood there with the pinot grigio and a stupid grin that suddenly felt glued to my face, and I swear I could feel my cheeks burning with the embarrassment of existing.

I tried to make eye contact with my mom, instinctively, like a child searching for a lifeline.

Normally, in any room, my mom was the anchor. The person you could read. If she was happy, the room was safe. If she was tense, you watched your mouth. If she was sad, you got quieter.

This time, she didn’t look at me at all.

She stared at the floor.

And the worst part is what my brain did with that.

I made excuses for her.

Oh, she’s overwhelmed, I told myself. She planned too much. She didn’t expect this many people. She’s nervous. She’ll look up and give me that little wink she does when she’s proud.

I was literally trying to comfort her in my own head while she was preparing to remove me from her life like a stain.

My dad—my dad, because I don’t know what else to call him yet—didn’t move. He stood by the fireplace the way he always stood when he wanted to look like he was in control of a room. Hands clasped, shoulders squared, chin slightly lifted.

He was holding a thick manila folder.

The kind of folder that doesn’t hold birthday cards.

The kind of folder that holds evidence.

I took one step into the kitchen and the crowd didn’t part like a party crowd would.

They held their positions.

And then my dad spoke, voice flat, practiced.

“We’ve been looking at the numbers, Maya,” he said, like he was opening a meeting. “We’ve been very generous.”

He didn’t say Happy birthday.

He didn’t say I love you.

He didn’t say anything that belonged in a family.

He extended the folder toward me like it was a bill.

My hands felt numb when I took it. I remember the paper’s weight. Heavy in a way that wasn’t physical. Heavy like the air before a storm.

I opened it expecting—honestly—I don’t know what I expected. Something dramatic but not cruel. A deed to a car. A scholarship announcement. Some weird surprise like “we bought you a condo.” Anything that would justify seventy-five silent relatives in my parents’ kitchen like they were about to watch a play.

The first page was a spreadsheet.

It was titled: M. Expenses 1996–Present.

I stared at it for a second because my brain couldn’t translate what I was seeing into meaning. It looked like something my boss would send out before budget season.

Then the words started to register.

Piano Lessons – Grade 4.

Braces.

ER Visit – 12 years old – broken arm.

School supplies.

Summer camp.

Birthday checks.

Field trips.

Clothes.

College application fees.

Every line item.

Every receipt of my childhood, turned into a ledger.

There was a total at the bottom.

Six figures.

I felt my mouth go dry.

My dad pointed to the next page.

The DNA results.

The room tilted, not like a movie spin, but like a subtle, sick shift—like the floor had stopped trusting me.

“The hospital made a mistake,” he said.

His voice didn’t tremble.

No tears. No cracking. No grief.

Just that same dead-even tone he used when he talked about property taxes or insurance deductibles.

“We raised a stranger,” he continued, “and we aren’t going to be responsible for the cost of a stranger’s life anymore.”

I sat down on the edge of the hearth without meaning to, like my body made the decision before my mind could catch up. The fire behind me was too hot on my back, but I couldn’t move. I just stared at the spreadsheet line that said Summer Camp 2008 and my brain latched onto it like it was the only safe thing in the room.

Not the DNA.

Not the word stranger.

Not the fact that my entire identity had just been tossed into the air like a plate.

Summer camp.

Because summer camp was real. I remembered the smell of sunscreen. The way the lake felt. The stupid crush I had on a counselor named Tyler.

That was the moment my mind did something that still makes me feel nauseous.

I wondered if he had saved the receipts.

Did he keep these in a box for twenty years?

Did he build this ledger slowly, over time?

Or did he sit down recently with a calculator like a man preparing to reclaim a debt?

The calculation felt more traumatizing than the news itself.

Because DNA can be a mistake.

But a man turning your childhood into an invoice?

That’s not an accident.

That’s a decision.

I didn’t argue. I didn’t say, But I’m your daughter.

I didn’t cry.

I think, in that moment, something in me went very still.

Like my heart stopped offering love and waited to see what it would cost.

And then I realized: for them, love was a transaction.

And the transaction had been voided.

If I wasn’t their biological asset, the contract was over.

It is a terrifying thing to understand that the people who tucked you in at night, who kissed your forehead when you had fevers, who clapped at your piano recitals—those people had been keeping a mental balance sheet the whole time.

A murmur rippled through the crowd.

Not sympathy.

Not outrage.

Something worse: curiosity.

And that’s when the clapping started.

Not everyone. Just a few at first. Like they didn’t know if it was appropriate to applaud a human being’s eviction from her own life.

Then more joined in—polite, brittle claps, the kind you give at the end of a church performance. The sound filled the kitchen like hail against windows.

I looked up, confused, heart numb, and saw her.

A woman sitting in the armchair in the corner—the one nobody ever sits in. The chair that usually holds folded blankets and old throw pillows. She stood with the confidence of someone who knew exactly why she was there.

She wore an expensive beige coat, sharp lines, corporate elegance. She looked like the older, more successful version of me. Like my future self had walked into the room to watch my past self dissolve.

She stepped forward, extending a hand.

“I’m Diane,” she said. “I represent the estate of Juliana Vance.”

Juliana Vance.

The name dropped into the room like a stone.

My dad didn’t look impressed. He didn’t look surprised either. He looked like this had been arranged. Like this wasn’t a tragedy—this was a process.

Diane spoke with the calm of a woman who lived in documents and deadlines.

“The other child,” she said gently, eyes on me, “the girl you were swapped with at birth… was Juliana.”

My throat tightened.

Swapped.

Like we were luggage.

Diane continued, “Juliana passed away last year due to a heart condition. During genetic screening for her siblings, her parents discovered she wasn’t biologically theirs.”

My stomach turned.

A year ago.

She had been alive a year ago.

A girl with my face, somewhere out there, living a life I never knew existed.

And she had died.

Diane’s gaze didn’t leave mine. She was careful, but not soft.

“They spent a year tracking you down,” she said. “They wanted answers. They wanted to know what happened. They wanted to know… you.”

Then Diane turned slightly toward my father.

“And you’re making a mistake with your ledger,” she added, voice sharpening. “It’s legally unenforceable, and morally bankrupt.”

My dad scoffed.

He actually scoffed.

Like morality was a child’s concept.

He looked at me again.

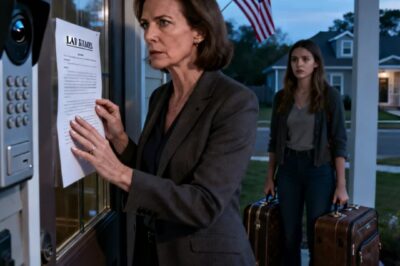

“You have an hour,” he said. “Your mother packed a suitcase for you. It’s by the door.”

It wasn’t a suitcase.

It was my old high school duffel bag.

That’s what broke me.

Not the DNA.

Not the word stranger.

Not the ledger.

The duffel bag.

Because it meant my mom had already gone into my old room—my old room with the faded posters and the drawer that still smelled faintly like my teenage perfume—and thrown my sweaters into a bag like she was clearing out a guest who overstayed.

While I was driving over thinking about cake flavors, she was packing my exit.

She’d decided I was gone before I even walked in.

I didn’t fight.

I wish I could rewrite this part into something brave.

I wish I could tell you I stood up and gave a speech about how blood doesn’t make a family and love isn’t a contract and they would regret this.

But I didn’t.

I felt heavy.

Like my bones had turned to lead and my muscles were made of wet sand.

I picked up the duffel bag.

I took the folder.

I didn’t say goodbye to the seventy-five relatives and neighbors who had come to watch.

I just walked through them.

It felt like moving through a graveyard of people who used to be mine.

Someone smelled like perfume I recognized from Christmas hugs.

Someone shifted away from me like I was contagious.

Someone whispered, “Oh my God,” like I was a cautionary tale.

The cold air hit me when I stepped outside.

I remember thinking the sky looked too normal.

In America, the world doesn’t pause for your heartbreak. The sun still shines. The flags still wave. The mail still gets delivered. Your life collapses and the street looks exactly the same.

I got in my car and drove to the Denny’s on Fourth Street.

I don’t know why.

It was just… there. Open. Bright. Neutral.

The smell of burnt coffee hit me like a slap. The booth seat was cracked. The table was slightly sticky. The waitress said “Hi, hon” like she’d said it to a thousand broken people before.

I ordered Moons Over My Hammy because it was the most ridiculous thing on the menu and I needed something ridiculous to happen. I needed my brain to catch on something absurd so it wouldn’t drown.

When the food came, I stared at it like it belonged to someone else.

Then I finally opened the DNA page.

0%.

No match.

No shared biology.

The words were clinical, but the meaning was feral. The kind of thing that tears at your identity with teeth.

I wasn’t theirs.

But then my eyes caught the other papers Diane had slipped into the folder.

Photos.

The Vance family.

They all had my chin. My hair. My shape. Their faces held familiar angles like déjà vu.

And there was a photo of Juliana.

The girl who died.

The girl I was swapped with.

She looked like my mother.

Not my biological mother—the mother I had just lost.

She had her smile.

The same kind of smile you can’t fake: warm, slightly crooked, like it’s trying to reassure you the world is still safe.

It hit me so hard I had to swallow to keep from making a sound.

Because in that moment, I understood something crueler than any ledger.

Everybody had lost.

My parents lost their real daughter years ago and didn’t even know it.

The Vances lost their daughter… then found out she wasn’t theirs either.

And me?

I was the leftover.

The clerical error.

The living proof of a hospital’s mistake.

I ate a piece of toast.

It tasted like cardboard.

And my brain—because brains are ridiculous—thought: I need to call work and take tomorrow off.

It’s wild how the mind clings to the mundane when your life is exploding. Like if you can just keep the routine intact, the disaster will feel less real.

I can’t come in tomorrow, I’m having a crisis felt too dramatic, so I emailed my boss and said I had food poisoning.

A few days later, I met the Vances.

My biological parents.

They weren’t private-jet rich, but they were lakehouse and organic-groceries rich. The kind of wealthy that smells like clean laundry and expensive hand soap. The kind of people who know what farmers market is best in three different towns.

They were kind.

They cried.

They hugged me for too long.

And I don’t say that to be ungrateful. I say it because the hugs didn’t feel like they were hugging me.

It felt like they were trying to squeeze the ghost of Juliana out of my ribs.

They wanted to make up for lost time.

They offered me money.

A place to stay.

Introductions to family members who looked at me like a miracle and a tragedy at the same time.

They asked me questions that were meant to be gentle but landed like pressure.

“Juliana loved horses,” they’d say. “Do you love horses?”

And I’d have to say no.

Not even no—I’m actually terrified of horses.

And I would watch the disappointment flicker across their faces before they hid it, before they forced a smile like it didn’t matter.

But it did matter.

Because I could feel it: I wasn’t what they’d hoped for.

I was a replacement part that didn’t quite fit the machine.

It’s been three months, and every time I see them, I feel like I’m auditioning for a role I didn’t prepare for.

Like I’m supposed to be grateful and grieving and curious and loving all at the same time, while my heart is still trying to figure out what it’s allowed to be now that my old family erased me with paperwork.

My therapist says my adoptive parents likely felt a sense of betrayal. That my existence felt like an intrusion, like a cuckoo bird in their nest.

But I’m the one who was betrayed.

I spent thirty years being who they wanted.

I played the piano. I got the grades. I was the good daughter. The reliable one. The one who didn’t cause trouble.

And it turns out that was only valid as long as the paperwork was correct.

I am angry.

But it’s not the kind of anger that screams.

It’s the kind that freezes.

The kind that makes you calm in a way that scares you because you realize you might never be warm like that again.

So where does that leave me?

I’m in a one-bedroom apartment now.

Neutral walls. Cheap blinds. No photos hung yet because I still don’t know which memories are mine to frame.

For a while, I was in a Motel 6, telling myself it was temporary like a person in denial telling themselves the sky isn’t falling while it lands on their head.

Now I have a real bed and a kitchen counter and a little stack of mail with my name on it, and that feels like progress, even though some nights I still wake up with that kitchen scene flashing behind my eyes.

The ledger my dad gave me is in a drawer.

I don’t know why I keep it.

Maybe because it reminds me that unconditional love isn’t as common as people pretend it is. Maybe because it keeps me from romanticizing them. Maybe because one day I’ll want to prove to myself I didn’t imagine any of it.

There’s still an unopened bottle of wine on my counter.

The gold foil is peeling.

It’s the same bottle I carried into their garage.

The bottle I thought I’d drink while someone sang happy birthday.

It’s funny—cruel funny—how objects become symbols without asking.

I think I’m waiting for a day when it’s just a bottle of wine again.

Not the bottle of wine I brought to the end of my life.

People ask me, “Do you hate them?”

And I don’t know how to answer because hate feels too clean for something this complicated.

I don’t hate them.

I don’t forgive them either.

Mostly, I pity them.

Imagine being so fragile that a piece of paper can erase thirty years of bedtime stories and scraped knees and Christmas mornings. Imagine living in a world where love is so conditional that it collapses the moment biology is questioned.

That has to be a lonely way to live.

I’m not fixed.

I’m not healed.

I’m just here.

I’m unpacking my books and deciding what I actually like, what I actually want, what parts of me were real and what parts were performance.

Some days I look at a paint color and realize I don’t know if I like it because I like it… or because it’s what my mother always chose, like my preferences were just extensions of hers.

Some days I feel like a person.

Some days I feel like an administrative error that learned to walk and talk and love before anyone corrected the file.

But I’m learning something, slowly, painfully.

If a family can disappear overnight, then maybe I’m allowed to build something new without begging anyone to approve it.

Maybe I’m allowed to stop auditioning.

Maybe I’m allowed to be messy.

And maybe the most American thing about this story—more than the suburbs and the fluorescent Denny’s and the motel off the highway—is that you can lose everything you thought was guaranteed…

and still wake up the next day with your name on a lease, a job to go to, and a quiet, stubborn pulse inside you that refuses to die.

I’m going to finish unpacking these books.

And one of these days, when the air feels less haunted, I’ll open that wine.

Not to celebrate them.

Not to mourn who I used to be.

Just to prove to myself that the story didn’t end in that kitchen.

It just… split.

And I’m still standing on the side that lived.

The first time I went back to their street, I didn’t even realize I’d turned the wheel.

That’s how muscle memory works in America—how your body can find a place your life no longer belongs to. One wrong exit, one familiar row of storefronts, and suddenly your hands are steering you toward the house that used to mean safety.

I caught it two blocks away.

The same maple tree by the stop sign. The same mailbox cluster. The same beige siding that blended into every other beige siding on the cul-de-sac like the neighborhood was designed to erase individuality.

My chest tightened so fast it felt like a seatbelt locking.

I pulled over by a park—one of those small suburban parks with a plastic playground and a flag pole that always looks slightly tilted. I sat there with the engine running, staring at nothing, while my heart tried to decide whether it was grieving, furious, or simply embarrassed.

I didn’t go closer.

I couldn’t.

Not because I was afraid of them.

Because I was afraid of what I’d do if they opened the door and looked at me like I was still theirs for a second.

Because the most humiliating part of this story—the part I don’t post on social media because it makes me look weak—is that even after they threw me out like trash, some sick part of me still wanted them to change their minds.

I wanted the apology that would rewrite everything.

I wanted my mom to come running down the driveway in her socks, arms open, crying, saying they were wrong, saying none of it mattered, saying love isn’t a spreadsheet.

But life doesn’t do rewrites.

Life does consequences.

I drove away and didn’t breathe normally until I hit the highway and the landscape turned into generic American blur—gas stations, fast-food signs, giant trucks carrying things you never see but somehow always need.

That night, in my one-bedroom apartment, I unpacked a box labeled “KITCHEN” and realized I didn’t own a single kitchen knife that wasn’t dull.

The kind of detail that feels pathetic until you understand what it represents.

I’d spent thirty years in a house where the drawers were already full.

Now I was building a life from empty spaces.

I sat on the floor, back against the cabinets, and laughed once—short, hollow—because the quiet was so complete it felt like punishment.

Then my phone buzzed.

A message from Diane.

Just three words:

“Are you awake?”

I stared at the screen for a long time before replying.

“Yeah.”

She called immediately.

Her voice was calm—professional calm—but there was something human under it, something like anger on my behalf.

“I wanted to check in,” she said. “Today was… violent.”

That word hit me weird.

Violent.

Nothing had physically happened, and yet my whole body agreed with her. Violence isn’t always bruises. Sometimes it’s paperwork weaponized. Sometimes it’s seventy-five people watching you get erased.

“I don’t know what I’m doing,” I admitted.

There was a pause.

“You’re surviving,” Diane said. “That’s what you’re doing.”

I swallowed hard.

“I keep thinking about the ledger,” I said. “Like—what kind of person saves receipts for twenty years?”

“A person who plans,” she said, voice sharper. “Or a person who wants leverage. Or both.”

I closed my eyes.

The image of my father’s face—flat, certain—floated up like a ghost.

“Why did they invite everyone?” I asked.

Diane exhaled. “Because they wanted witnesses. They wanted to control the narrative. They wanted you to feel too ashamed to fight back.”

My stomach twisted.

It made sick sense.

Shame is an American weapon. We pretend it’s “accountability,” but it’s really just social control wrapped in polite clothing.

“What about the Vances?” I asked quietly. “They’re… nice. But it feels like I’m disappointing them by existing.”

Diane’s voice softened. “That’s normal. They’re grieving. And you’re not a replacement for Juliana. No one is.”

The name again.

Juliana.

The girl who lived my life and died with my face.

“Do you know where she’s buried?” I asked.

Diane hesitated.

“Yes,” she said gently. “But I don’t know if that’s a good idea yet.”

“I don’t know if anything is a good idea,” I whispered.

She didn’t argue.

Instead, she said, “Tomorrow morning, I’m coming by with documents. There are practical things we need to handle.”

“Like what?”

“Identity,” she said. “Birth records. Legal name issues. Medical history. And… there’s the estate.”

My throat tightened. “The estate?”

Diane paused.

“Juliana’s parents created a trust,” she said carefully. “When they realized she wasn’t biologically theirs, they were already deep into estate planning because of her heart condition. When she passed, the trust became… complicated.”

I stared at the wall, suddenly cold.

“I don’t want their money,” I blurted.

“I didn’t say you did,” Diane replied, calm. “But you need to understand what’s happening, because your adoptive parents are already trying to position themselves as… wronged parties.”

I sat up straighter. “How?”

Diane’s voice went icy. “They’re hinting that they deserve compensation. That they should be reimbursed.”

The ledger again, crawling into my stomach like a parasite.

“I knew it,” I whispered.

“They’re also implying,” Diane continued, “that you were going to be ‘taken care of’ by the Vances, which makes it easier for them to justify cutting you off.”

“Cutting me off?” I repeated, like it was still shocking.

I heard Diane’s papers rustle on the other end.

“I pulled your parents’ public records,” she said. “Your father refinanced the house last year. He has debt. They’re not as stable as they pretend. That ledger wasn’t about principle. It was about fear.”

Fear.

That changed something in me—tiny, but real.

Because fear meant this wasn’t just cruelty.

It was weakness dressed up as righteousness.

Diane continued, “The Vances want to meet you again. They want to talk—without pressure, without a crowd, without your adoptive parents present.”

My stomach clenched.

“Tell them…” I started, then stopped.

Tell them what?

Tell them I’m trying? Tell them I’m scared? Tell them I don’t know how to be someone’s daughter twice?

I swallowed.

“Tell them okay,” I said finally. “But not at their house.”

“Agreed,” Diane said. “Neutral ground.”

After we hung up, I stood in my kitchen and stared at the unopened wine.

My thirty-year-old birthday bottle.

The bottle that felt like a witness.

I didn’t open it.

Instead, I went to the bathroom and looked in the mirror like I was trying to identify a stranger.

Same face.

Same eyes.

But now everything behind them felt unstable, like the story of me had been rewritten and nobody sent me the updated script.

The next morning, I met Diane in a coffee shop that smelled like cinnamon and burnt espresso—one of those places in a strip mall that tries to feel artisanal but still has the same fluorescent hum as every American chain store.

Diane wore the same sharp coat, hair pulled back, expression controlled. She slid into the seat across from me with a thick folder—another folder—like my life had become a series of documents.

“First,” she said, “I’m going to tell you something you need to hear.”

I stared at her.

“You didn’t do anything wrong,” she said.

My throat tightened.

“I know you’ve heard that,” she continued, “but you need to understand it in your bones. The adults in this story failed. Not you.”

I looked away fast, because if I held eye contact I would cry, and I was tired of crying in public.

Diane opened the folder.

There were forms. Official letters. Copies of hospital records. A timeline of the birth mix-up that looked like a legal thriller.

“This happened in 1996,” she said. “Two babies. Same hospital. Same shift. A nurse error. It’s rare, but it happens.”

Happens.

Like it was a storm. Like it was weather.

“And Juliana’s parents?” I asked.

Diane’s expression softened. “The Vances are… decent people. They loved Juliana. They still love her. They’re not trying to replace her with you.”

I let out a breath I didn’t know I’d been holding.

“Then why does it feel like they are?” I whispered.

Diane’s eyes stayed steady. “Because grief makes people reach. And because you look like her, and that’s… intoxicating. It makes them think they can cheat death.”

Cheat death.

That phrase settled into my skin.

“So what happens now?” I asked, voice rough.

Diane slid one document toward me.

“Juliana’s estate included a letter,” she said. “She wrote it when she was sick. She didn’t know about you, but she wrote about… identity.”

My pulse jumped. “Can I read it?”

Diane hesitated. “Yes. But not here.”

She tucked it back into the folder.

“First,” she said, “you need to protect yourself. Your adoptive parents might escalate. If they try to publicly shame you or interfere with legal records, we’ll respond.”

Respond.

We.

The word landed like a small lifeline.

Because for months, I’d been alone in the wreckage.

And now there was someone with a plan.

After coffee, Diane drove me to a quiet park by the lake. The wind off the water was sharp, that Midwest bite that wakes you up whether you want it to or not. We sat on a bench with the folder between us.

Diane finally handed me the letter.

The paper was creased, like it had been held too many times.

My hands shook as I unfolded it.

The handwriting was neat, rounded, feminine.

I felt dizzy.

Juliana’s hand.

Juliana’s words.

To the world.

To no one and everyone.

I read it slowly.

Not because it was long.

Because every sentence felt like stepping on glass.

She wrote about feeling like she didn’t quite belong in her own body. About doctors’ offices and tests and the loneliness of being “the sick one.” About watching her parents try to stay hopeful and seeing the fear they hid.

And then she wrote something that made my breath catch:

“If I’m not here one day, I hope the people who love me don’t try to trap me in a story that can’t hold them.”

My eyes blurred.

Diane watched me carefully, like she didn’t want to intrude on something sacred.

Juliana’s letter wasn’t about me.

But it felt like it was reaching for me anyway.

Because my adoptive parents had trapped me in a ledger.

My biological parents were trying not to trap me in Juliana.

And I was trapped in the space between.

I folded the letter, hands trembling.

“She sounds… kind,” I whispered.

“She was,” Diane said quietly. “She was also smart. And tired. And very aware.”

The wind shifted.

I looked out at the lake—gray, endless, American in its size and indifference.

“What do I do with this?” I asked.

Diane’s voice stayed gentle. “You don’t have to do anything yet. But you can let it remind you of something.”

“What?”

“That you are not a mistake,” Diane said. “You are a person who happened because of a mistake.”

That distinction hit me like a clean blade.

I swallowed hard, nodding once.

Then Diane glanced at her phone. “The Vances are nearby. They want to meet for ten minutes. Just to talk. Are you okay with that?”

My stomach twisted, but I forced myself to nod.

Ten minutes felt survivable.

The Vances arrived in a black SUV that looked too polished for a public park.

My biological mother—Elena Vance—stepped out first, wearing sunglasses even though the sun was weak. She moved like she’d been holding herself together for months with sheer will. My biological father followed, jaw tight, hands shoved into pockets like he didn’t know what to do with them.

They approached slowly, like they were afraid I might run.

Elena’s lips trembled when she saw me up close.

“You look…” she started.

I already knew what she was going to say.

You look like her.

You look like us.

You look like the life we lost.

I didn’t want to be anyone’s wound.

So I spoke first.

“Hi,” I said, voice steady enough to surprise me.

Elena’s eyes filled instantly. She nodded, swallowing.

“Hi,” she whispered back.

They sat on the bench across from me, leaving space between us like a buffer.

For a moment, nobody spoke.

Then Elena took off her sunglasses.

Her eyes were red-rimmed.

“I’m sorry,” she said.

That was different.

Not “we’re so happy.”

Not “we’ve been waiting.”

Not a line meant to hook me into a role.

Just sorry.

“For what?” I asked, because my brain always wants specifics when emotions are too big.

“For the pressure,” she said, voice cracking. “For… needing you to be okay. For needing you to be anything.”

Her husband—Mark—cleared his throat. “We loved Juliana,” he said, voice rough. “And we still do. We’re not trying to replace her.”

I nodded slowly, but my body stayed tense.

Elena leaned forward slightly. “We don’t know how to do this,” she admitted. “We’re learning. We’re stumbling. We’re grieving, and grief makes you… stupid.”

A short laugh escaped her, bitter and embarrassed.

“I asked you about horses,” she said softly. “That was… ridiculous.”

I felt my throat tighten.

“Yes,” I said, honest. “It was.”

Elena nodded, tears spilling. “I’m sorry.”

I took a breath.

I didn’t want to comfort her.

I didn’t want to be the strong one again.

But I also didn’t want to keep carrying the weight alone.

So I said the truth.

“I’m scared,” I admitted. “I feel like every time I see you, I’m failing some test I didn’t sign up for.”

Mark’s face tightened, pain flashing.

Elena nodded hard. “That’s fair,” she said. “That’s fair. We won’t do that to you.”

She wiped her face with the heel of her hand, messy, human.

“We just…” her voice broke. “We just don’t want to lose you too.”

That sentence landed in my chest like a warm, terrifying thing.

Lose you too.

I swallowed, forcing myself to breathe.

“You don’t get to own me,” I said quietly. “Not after what I just went through.”

Elena nodded immediately. “We know.”

Mark nodded too, jaw clenched.

Elena took a shaky breath. “Can we start small?” she asked. “Coffee. Lunch. No expectations. No comparisons. Just… learning who you are.”

I stared at her for a long moment.

Something in her tone—less desperate, more humble—made it feel possible.

“Okay,” I said. “Small.”

Relief flooded Elena’s face so fast it almost hurt to watch.

Diane stood a few steps away, giving us space, but I saw her posture relax slightly, like she’d been holding her own breath.

Mark cleared his throat again. “And about the trust,” he said. “We want you to know—we didn’t create it because of you. It was for Juliana. But the law is… complicated. Diane will explain. We’re not using it as leverage.”

Leverage.

That word snapped through me like a wire.

I thought of the ledger.

The total.

The coldness.

The suitcase by the door.

I looked Mark in the eyes.

“If money comes with strings,” I said, voice hardening, “I don’t want it.”

Elena shook her head fast. “No strings,” she said. “None.”

I nodded once.

We sat there for another few minutes, talking about nothing important. Weather. Work. The kind of conversation strangers have when they’re trying to be gentle with each other.

It was awkward.

It was imperfect.

But it wasn’t cruel.

And after what I’d survived, not cruel felt like a miracle.

That night, back in my apartment, I stared again at the wine bottle.

I realized something, slowly.

My adoptive parents didn’t just take my family away.

They took my idea of myself.

They made me question whether love was real.

Whether memories were valid.

Whether I deserved stability.

But sitting on that park bench, hearing Elena admit she didn’t know how to do this, hearing her apologize without conditions…

It cracked something open.

Not forgiveness.

Not healing.

Just… possibility.

I went to the counter.

I picked up the bottle.

The gold foil flaked under my thumb.

And for the first time since my birthday, I didn’t feel like it was a symbol of the end.

It felt like a choice.

I didn’t open it yet.

But I set two glasses beside it.

Just in case.

Because if my life had taught me anything in the last three months, it’s this:

You can be erased by paperwork.

You can be displaced by a mistake.

You can be thrown out of a house you thought was yours.

And still—somewhere in the middle of a fluorescent coffee shop and a windy park and a small apartment with unpacked boxes—you can start building something that’s actually yours.

Not a transaction.

Not an audition.

Not a replacement.

A life.

And this time, if anyone wanted to be in it…

They’d have to love me without keeping a ledger.

News

My mom laughed in front of the whole family…”how does it feel to be useless, daughter?”. I looked at her calmly and said, “feels great… Since I just stopped paying your rent. “Her smile vanished. My dad froze, then shouted, “what rent!? Why?”

The garlic hit first. Not the warm, comforting kind that says family and Sunday gravy—this was sharp garlic, cooked too…

I arrived at my daughter’s wedding late – just in time to hear her toast: ‘thank god she didn’t come.’ I quietly left. The next day, the wedding gift I’d prepared for her husband revealed everything she’d been hiding from him.

The first thing I heard was laughter. Not the sweet, champagne-bubbly kind you expect at a wedding. This was sharper….

My mom used her key to move my golden child sister in. I called 911 and they were kicked out. 2 days later, mom returned with a locksmith claiming “tenants’ rights.” I had her arrested again.

The first scream wasn’t human. It was metal. A power drill biting into reinforced steel makes a sound you don’t…

My sister stole my identity, opened credit cards in my name, ran up $78k in debt. My parents said: “just forgive her, she’s family.” I filed a police report. At her arraignment, my parents showed up-to testify against me. Judge asked 1 question that made my mother cry.

The envelope was thick enough to feel like a threat. It landed in my mailbox on a Tuesday like any…

My sister-in-law tagged me in a post: “so blessed to not be the struggling relative my daughter saw it at school. Kids laughed. I didn’t comment, didn’t react. But Friday, her husband’s hr department sent an email: “the Ceo requests a meeting regarding departmental restructuring…”

Aunt Vanessa’s Instagram post detonated at 7:13 a.m., right between the weather alert and the school district reminder about picture…

“We’re worried about your finances,” mom said. I clicked my garage remote. “that’s my Lamborghini collection. The blue one’s worth $4.8 million.” dad stopped breathing.

The chandelier above my parents’ dining table glowed like a small, obedient sun—warm, expensive, and completely indifferent to the way…

End of content

No more pages to load