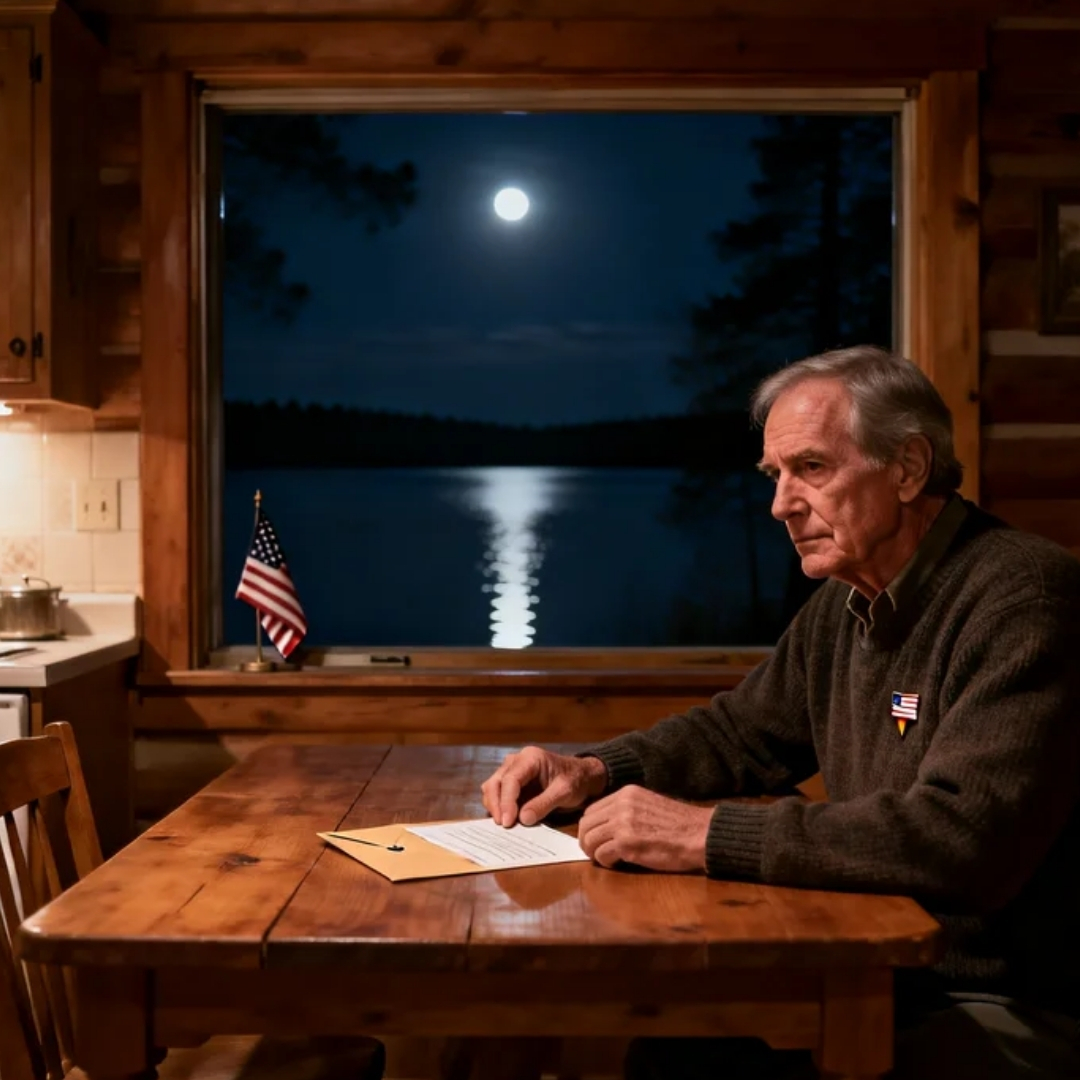

The envelope waited on my desk like a tiny coffin—bone-white paper, no return address, only a raised notary seal that caught the lamplight the way a badge catches a camera flash.

Outside my window, the lake lay dark and flat as spilled oil. Somewhere in the pines, an owl called once and quit, as if it didn’t want to be a witness.

I didn’t open the envelope right away. I sat there with my hands folded and listened to the house settle—wood ticking, a faint sigh in the walls—like it was holding its breath with me. Tomorrow morning my son would walk through my front door with the easy confidence of a man who believed the world was a spreadsheet and every cell belonged to him eventually.

He thought he was coming to take possession.

What he didn’t know was that I’d already signed the thing that would end everything he’d planned.

My name is David Thornton. I’m sixty-seven years old, and I’m about to teach my only child the most expensive lesson of his life.

It started three months ago, in November, when the maples around my place stood naked and gray and the wind off the water had teeth. I was closing the cottage for the season—pulling the dock ladder, draining the lines, stacking split oak by the door—when a black Mercedes eased up my gravel drive like it owned the stones.

That should’ve been my first warning.

Michael never visited in November. Michael didn’t visit in any month that didn’t come with a holiday photo-op. He ran an architecture practice out of the city, the kind with glass walls and minimalist furniture that looked uncomfortable on purpose. He lived by calendars and networking dinners and phrases like “value creation.” My cottage—twelve acres on a quiet American lake, old-growth pines, shoreline that curved like a protective arm—was, in his words, “a rustic shack.”

The Mercedes door clicked open, and he unfolded out of it in a tailored coat that probably cost more than my fishing boat. His wife, Clare, followed in heels better suited to a Manhattan sidewalk than frost-bitten cottage country. Clare was a real estate developer. The kind who used words like “revitalization” while erasing entire neighborhoods. The kind who could look at a century-old home and see only the square footage hiding inside it.

Michael didn’t hug me.

“Dad,” he said, brisk as a business call. “We need to talk.”

I had an armful of firewood. I was always carrying something. I’d been carrying firewood when Margaret died ten years ago, carrying groceries when Michael got married, carrying the quiet weight of being forgotten. Carrying things is what you do when the other person doesn’t carry you.

“Come inside,” I said. “I’ll put on coffee.”

“This won’t take long,” Clare said.

Her smile was polished, sharp-edged, practiced. The kind you see on local news right before someone says, “We regret to inform you…”

They didn’t wait for the coffee. They didn’t take their coats off like they belonged.

We stood in my kitchen—the kitchen where Margaret taught Michael to flip pancakes, where Christmas mornings smelled like cinnamon and wet mittens, where I held my wife when the cancer made her small and angry and brave.

Clare pulled out a tablet and flicked through glossy renderings with her finger. Buildings bloomed across the screen: glass, steel, lighted terraces, a marina, a spa. Helicopter pad. Private docks. Everything clean and modern and wrong.

“The Lake Marlowe Development Project,” she said, like she was unveiling a cure. “Luxury resort. Spa. Restaurant row. We’re talking about forty million dollars of investment in this area. Jobs. Tourism. A real transformation.”

I looked at the screen and saw the future: infinity pools where loons used to nest, a wide road cut through pines that had stood since my grandfather was young. I saw Margaret’s ashes scattered under those trees, turned into a marketing brochure.

“That’s nice,” I said. “What’s it got to do with me?”

Michael stepped forward, tall, broad-shouldered, educated at the kind of place that teaches you confidence the way some people teach prayer.

“Your property,” he said. “This cottage. The twelve acres along the lake. It’s the keystone parcel. Everything hinges on this location.”

My father bought this land in 1952 for three thousand dollars and built the cabin log by log with hands that never learned to quit. Margaret and I raised Michael here. Every summer. Swimming off the dock. Fishing at dusk. Campfire smoke in his hair.

Or so I thought.

“It’s not for sale,” I said.

Clare’s smile didn’t move.

“Mr. Thornton,” she said, “we’ve already secured every other property we need. Permits are in motion. Investors are committed. But we need your land. Without it, the project collapses.”

“Then I guess it collapses,” I said.

That’s when Michael’s voice changed.

Harder. Colder. Like a door shutting.

“Dad, you’re getting older,” he said, and there it was—the word “older” said like a diagnosis. “This place is too much for you. You’re isolated out here. No neighbors close. What if you fall? What if you have a stroke? Who finds you?”

“I’m healthy,” I said. “Probably outlive you at the rate you run yourself into the ground.”

Clare laid a hand on his arm—affection disguised as control, like she was holding back a dog that wanted to bite.

“We’re prepared to offer you two point six million dollars,” she said. “That’s well above market value. You could buy a condo near the city. Be closer to Michael. Better healthcare. Security.”

Two point six million.

For the land my father protected with his life’s work. For the trees where Margaret became part of the earth. For forty years of mornings that tasted like lake air and coffee and promise.

“No,” I said.

Michael slapped his palm down on my counter, and the sound cracked through the cabin like a starter pistol.

“Dad,” he snapped, “I’m trying to be respectful, but you need to understand reality. I’m an architect. Clare’s a developer. We know what this is worth. We know its potential. And we know you’re not thinking clearly.”

“I’m thinking fine,” I said. “Are you?”

Clare reached into her bag and pulled out a thick manila folder, the kind you see in courtrooms and hospitals.

“Because,” she said softly, almost kindly, “we’ve documented some concerning behaviors.”

She flipped it open. Papers. Typed statements. A couple of forms with physician letterheads.

“You forgot Michael’s birthday last March,” she said, as if that proved anything except how long he’d been tallying my mistakes. “You called him twice on a Tuesday asking if he was coming for Thanksgiving—both calls fifteen minutes apart. And you told a neighbor that Margaret was visiting her sister.”

My hands went cold.

“I never said that,” I said, the words coming out too fast, too sharp. “Margaret’s been gone ten years. I would never—”

“We have a sworn statement,” Clare said. “And we have medical opinions from two physicians who reviewed your case file.”

“What case file?” I said. “I haven’t seen a doctor in years beyond my checkup.”

Michael’s face was stone.

“Dad, we’re trying to help you,” he said, and the lie sat between us like a dead thing. “But if you won’t accept help, we have legal options. A competency hearing. We can petition the court. Have you declared unable to manage your affairs. Then a guardian sells the property anyway.”

The room didn’t spin from confusion.

It spun from rage.

“You’d do that to me?” I said. “Your own father?”

“If we have to,” Michael said. His eyes didn’t even blink. “Sign the papers, take the money, move closer, or we file next week. Your choice.”

They left the folder on my counter like a threat with staples.

After their tires crunched back down the gravel, I sat in the kitchen until the light died and the windows turned black mirrors. Something inside me broke—not the loud kind of breaking, but the quiet one, the final crack in a foundation you didn’t realize was failing.

Then I picked up the phone and called the only person I knew who wouldn’t flinch.

“James,” I said when he answered, “I need your help.”

James Whitmore had been my friend since we were eighteen. We met freshman year at a state university, pledged the same stupid fraternity, and survived enough nights that should’ve taught us better judgment. He became a real estate attorney in Boston—sharp as a razor, rich in a way that seemed unreal when you’d grown up counting quarters for gas.

And he owed me.

In 1983, when his life was coming apart and his first practice was sinking, I loaned him fifteen thousand dollars—money Margaret and I could barely spare. I never asked for it back. I never mentioned it again. But favors like that don’t disappear. They wait.

It was ten at night. I never called late.

“David?” James said, instantly alert. “What’s wrong?”

I told him everything—Michael’s visit, Clare’s renderings, the threats, the folder full of lies pretending to be medicine.

There was a silence on the line long enough to make my throat tighten.

Then James said four words that changed the shape of the next three months.

“Don’t sign anything.”

“What do I do?” I asked.

“Wait,” he said. “I need to make calls. Can you get to Boston tomorrow?”

“I can drive down,” I said.

“Good,” he replied. “My office. Two p.m. Bring that folder.”

That night I didn’t sleep. I sat by the window and watched moonlight scrape across the lake, remembered Margaret’s hand guiding Michael’s small fingers as he tried to skip stones.

“It’s all in the wrist,” she’d say. “Gentle, sweetheart. Like you’re petting a kitten.”

Michael’s first fish—a smallmouth bass, maybe two pounds—had made him dance like he’d caught a monster. Margaret took a photo. I still had it: seven years old, gap-toothed grin, holding up that fish like it was gold.

On his sixteenth birthday, I saved for two years to buy him a used canoe. Red fiberglass, scuffed and solid. I painted “S.S. Michael” on the stern like a joke and a blessing. He hugged me so hard I couldn’t breathe.

“Best present ever,” he said. “I’m keeping this forever.”

Forever lasted eight years. The canoe rotted in his garage until it became, in his words, “a storage problem.”

The next day I drove to Boston with my jaw clenched so hard my teeth hurt.

James’s office sat high above the city in a building made of reflective glass, the kind that turns the sky into a commodity. His secretary handed me coffee in a delicate cup. Everything there felt expensive, like the air cost money.

James read the documents for twenty minutes without speaking. His face didn’t change, but I could see something in his eyes hardening.

Finally he looked up.

“This is garbage,” he said flatly. “Manufactured. These physician ‘opinions’ are not diagnoses. I know both doctors. They never examined you. They gave opinions based on information provided by ‘family.’ It’s hearsay dressed up in a lab coat.”

“Can they do it?” I asked. “Can they drag me into court?”

“They can try,” James said. “They’d likely lose, but you’d spend six months bleeding money and dignity. Fifty grand in fees, at least. Evaluations. Testimony. Public records. They’ll make it ugly on purpose.”

I felt something cold crawl up my spine.

“So what do I do?” I asked.

James leaned back, steepled his fingers, and smiled like a man who’d just found the lever that moves the world.

“You sell the property,” he said.

My heart dropped through my ribs.

“What?”

“Not to them,” James said. “To someone else. Before they file. You’re competent right now. You have every right to sell your own land. Once it’s gone, there’s nothing for them to fight over.”

“I don’t want to sell to anyone,” I said.

“David,” he said, gentler, “they’re not going to stop. Even if they lose, they’ll appeal, they’ll harass you, they’ll keep you in motion until you’re too tired to stand. I’ve seen it. Greedy children who can’t wait for their parents to die.”

I stared at my hands—the hands that built docks and fixed engines and held Margaret’s when she could barely hold herself.

“What if,” I said slowly, “I sell it to someone who will never develop it? Someone who will keep it wild.”

James raised an eyebrow.

“You know someone like that?”

“The land trust,” I said. “Hudson Valley Heritage Land Trust. They preserve property. Conservation easements. They keep places exactly as they are.”

James didn’t waste time.

He made calls. He moved pieces.

By four o’clock, a woman named Patricia Chen walked into his conference room wearing practical boots and a fleece vest and the kind of expression you see on people who still believe in something.

“Mr. Thornton,” she said, shaking my hand like it mattered, “your land is ecologically significant. Old-growth forest. Shoreline habitat. We’d be honored.”

Then she opened her laptop and the reality appeared in rows and columns.

“The problem,” she said, “is funding. We could raise maybe one point eight million quickly. Grants, donors, capital campaign. But not two point six. Not on short notice.”

“What if you didn’t have two months?” I asked.

Patricia’s mouth tightened.

“Then we couldn’t do it,” she said. “We don’t have that cash on hand.”

James cleared his throat, the way he did when he was about to make the kind of suggestion that changes people’s lives.

“What if,” he said, “Mr. Thornton sold to you for one point eight million, and donated the difference as a charitable gift?”

Patricia blinked.

“An eight-hundred-thousand-dollar donation,” James continued. “Tax-deductible. He protects the land. You get the property. Everyone wins, except the people trying to bully an old man out of his home.”

I watched Patricia do the math in her head, watched hope rise carefully like a cautious animal.

“When would we need to close?” she asked.

James smiled. “How fast can you move?”

Patricia’s eyes flicked to her calendar.

“I can move fast,” she said. “But our financing needs a timeline.”

James tapped his pen on the table.

“How about March first?” he said.

March first.

It landed like a stone in my chest, heavy and perfect.

That date was one week before Michael’s big investor presentation—his grand reveal, his champagne-and-handshakes moment. One week before he planned to stand in front of money people and sell them a future built on my land.

Patricia held out her hand.

“March first,” she said. “You have a deal, Mr. Thornton.”

That night I drove home through dark highways and winter fields, stopped at a Dunkin’ Donuts off an interstate exit, and sat in the parking lot with my phone glowing in my hand.

I called Michael.

“Dad?” he answered, surprised, like he’d expected me to disappear quietly.

“I’ve thought about your offer,” I said. “I need time. It’s a big decision.”

I heard relief in his voice—the soft exhale of a man who thinks he’s already won.

“Of course,” he said. “Take all the time you need. We’re not trying to pressure you.”

Liar.

“There is one thing,” I said.

“Sure.”

“The money,” I said. “Two point six. How does that work?”

“Wire transfer,” he said quickly. “Once you sign, funds hit your account within twenty-four hours. Easy.”

“And your project,” I said. “When does construction start?”

“Groundbreaking March tenth,” he said, pride swelling like a balloon. “Big ceremony. Investors flying in from New York, California, maybe even overseas. It’s going to be incredible, Dad. This puts this lake on the map.”

The lake was already on the map. It just wasn’t on the map of people who confuse heritage with granite countertops.

“Sounds exciting,” I said. “Let me think about it.”

“Just don’t wait too long,” he warned. “Investors get antsy.”

Over the next three months, I played my role perfectly.

I became the version of me they wanted: forgetful, hesitant, a little uncertain. I asked questions twice. I let silence stretch. I let Michael call every two weeks like clockwork.

“Dad, have you thought more about the offer?”

“I’m still considering,” I said. “It’s a lot.”

“Time’s running out,” he’d say, always the same line. “We need an answer by February.”

February came.

I signed papers.

Not his papers.

Patricia’s.

Sale to the Hudson Valley Heritage Land Trust: one point eight million dollars.

Closing date: March first.

James handled everything—drafted the documents, coordinated financing, arranged the conservation easement so tight it might as well have been welded into the ground. County clerk filings. Notary stamps. Clean, legal, irreversible. The kind of quiet work that doesn’t make headlines until the moment it explodes.

Michael called on February fifteenth.

“Dad, we need to finalize,” he said, too cheerful, like he was already shopping for champagne. “Groundbreaking is March tenth. We have to close by March first, latest.”

“March first,” I said. “That’s an interesting date.”

“Can you do it?” he pressed.

“Oh,” I said softly, “I can do it.”

“Great,” he said, rushing forward. “Clare will come by tomorrow with the papers.”

“No need,” I said. “I already signed.”

Silence.

Then— “You… signed when?”

“This morning,” I said. “Everything’s finalized. Closing is March first. Just like you wanted.”

His voice lifted, pure relief, pure greed.

“That’s fantastic,” he said. “You won’t regret it. This is the smart decision.”

“I know,” I said. And I meant it.

March first arrived cold and clear. James drove up to witness closing. Patricia came with a photographer from the trust. They took pictures of the shoreline, the pines, the trail that curled past the rock where Michael used to sit and pretend he was a pirate.

We signed at my kitchen table. The same table where Michael carved his initials in 1987, and I never sanded them out.

When the wire hit my account—two forty-seven p.m.—the number looked unreal. One point eight million dollars. More money than I’d earned in decades working outdoors, protecting parks and trails and other people’s “resources.”

At three o’clock, my phone rang.

Michael.

“Dad,” he said, almost laughing with excitement, “great news. Investors loved the proposal. We’re set for groundbreaking next week. Are you coming to the ceremony? We’d love to have you there. Photo op, you handing over the property—real heartwarming.”

“Michael,” I said, steady as a lake in winter, “I need to tell you something.”

“What’s up?”

“I sold the cottage,” I said.

A beat.

“I know, Dad,” he said, confused. “That’s what we’re talking about.”

“No,” I said. “I sold it to the Hudson Valley Heritage Land Trust. Closed this afternoon.”

The silence on the line was so complete I thought the call had dropped.

Then, faintly— “What?”

“The land trust,” I said. “They’re preserving it. No development. Ever. It’s protected in perpetuity.”

“You can’t—” Michael’s voice cracked, disbelief turning sharp. “We had a deal.”

“You had a threat,” I said. “You threatened to have me declared incompetent. You tried to bury me under fake medical paperwork. So I sold to someone who respects what this place is.”

In the background I heard Clare’s voice rise—first confusion, then rage.

“What did he do?” she screamed, a raw sound, unpolished, the mask falling off in real time.

Michael wasn’t even talking to me anymore. He was talking to her, scrambling.

Clare’s scream became words. Accusations. Panic.

Then Michael came back on the line, and the calm businessman voice was gone. In its place: fear.

“Dad,” he said, shaking, “do you have any idea what you’ve done? The investors—forty million—everything is contingent on that land.”

“I know,” I said.

“We’ll sue,” he spat. “We’ll sue you for breach of contract.”

“What contract?” I asked. “I never signed anything with you.”

“We have emails,” he said. “Conversations—”

“You have nothing,” I said. “I never agreed. I said I’d think about it. I said I needed time. Just like you told the doctors you found to write their little opinions.”

Clare snatched the phone.

“Mister Thornton,” she hissed, voice vibrating with fury, “you don’t understand the damage. This project was going to create jobs. Contractors. Tourism. You’re destroying livelihoods.”

“Clare,” I said, “I don’t care.”

And I didn’t. Not about her talking points. Not about her rehearsed lines. Not about her sudden love for workers she’d never meet.

“You tried to destroy the one place on earth that mattered to me,” I said. “You thought I was an easy mark. A quiet old man you could push around. You were wrong.”

“We’ll sue the land trust,” she barked. “Tortious interference. We’ll—”

“Good luck,” I said. “It’s a registered nonprofit. The easement is filed. I had every right to donate. In fact, I get a charitable deduction for my ‘generosity.’ So thank you.”

There was a sound in the background—glass breaking. Something thrown. Something expensive meeting a hard surface.

Michael came back on, breathing too fast.

“Dad,” he pleaded, and it hit me then—this was the first time in years he’d sounded like my son. Not because he missed me. Because he’d lost control.

“Please,” he said. “There has to be a way to fix this. We can negotiate with the trust. Buy it back.”

“Protected in perpetuity,” I said. “That’s what the covenant says. They can’t sell it. Not to you. Not to anyone. It’s wilderness forever.”

“You ruined us,” he whispered. “The investors will pull out. We’ll be sued. The firm will collapse.”

“Then you’ll know how it feels,” I said quietly, “to have everything taken by the people you trusted most.”

I hung up.

James poured two fingers of whiskey and handed me the glass like a peace offering. We sat on the porch and watched the sun sink into the water, turning the lake into copper.

“How do you feel?” James asked.

I took a sip. It burned, clean and honest.

“Lighter,” I said. “Like I put down something I’ve been carrying for forty years.”

“He’ll come around,” James said, like he’d seen a hundred families twist and untwist.

“Maybe,” I said. “Maybe not. Either way, I’m done carrying him.”

A week later I moved into a small two-bedroom house closer to town—near the hospital, the grocery store, all the practicalities Michael swore I needed. The irony tasted bitter and sweet.

The land trust sent photos once a month. The cottage was designated a historical site. They offered educational tours, families and school groups walking trails that used to be mine alone. Kids learning bird calls where Margaret scattered wildflower seeds. People being taught, gently, what we lose when we pave everything for profit.

Michael emailed me three months after closing.

The firm declared bankruptcy. We lost everything. Clare left. I’m in a studio now. Entry-level job like I’m twenty-five again. I hope you’re happy. You destroyed my life.

I wrote back one sentence.

I didn’t destroy your life. I saved mine.

He never responded.

Sometimes I drive up to the lake and park in the new visitor lot the trust built. I walk the trail past the old pines and let the wind off the water slap my face the way it used to. I watch families picnic where Michael and I fished, watch kids laugh in the same places we once laughed, and I feel the strange peace of knowing something I loved will outlive all of us.

Last month I saw a boy about seven—dark hair, gap-toothed grin—skipping stones with his father. Their heads bent together like a secret. The father’s hand rested on the boy’s shoulder, gentle and sure.

“It’s all in the wrist, buddy,” the father said. “Like you’re petting a cat.”

The boy’s stone skipped four times. He whooped. The father laughed, and they hugged like the world was still safe.

I watched them longer than I meant to, remembering and mourning—not for what I lost with Michael, but for what Michael lost with himself.

He had everything that mattered—love, roots, a place that held his history in its soil—and he traded it for a development deal that would’ve made him money he didn’t need while destroying the only thing that ever made him whole.

That’s the real tragedy.

Not that I won.

That he chose to lose.

I’m sixty-seven years old. I live alone. My wife has been gone ten years. My son doesn’t speak to me.

But every night I sleep like a child, because I kept my promise—to Margaret, to my father, to every stranger who will walk those trails and swim in that lake and learn, maybe without even realizing it, that some things are worth more than money.

Michael thought he could audit me, measure my mind, assign my value from paperwork and polished threats.

But I audited him first.

And he came up short.

The rage is gone now. All that’s left is peace—and the certainty that sometimes the best revenge isn’t destruction.

It’s preservation.

The envelope on my desk is still unmarked, still sealed, still heavy with finality. Tomorrow my son will walk through that door expecting to take possession.

He’ll find out what the quiet ones know.

When you mistake silence for weakness, you don’t just lose the argument.

You lose everything you thought you owned.

The first night after everything went quiet, I didn’t sleep.

Not because of fear. Not because of doubt.

Because silence has weight when it finally arrives.

The house I’d bought sat on a modest street lined with maples and mailboxes shaped like little barns. Somewhere down the block a television murmured through thin walls, a laugh track rising and falling like a tide. A police helicopter passed overhead once, rotors chopping the air—another reminder that I wasn’t tucked away in the woods anymore. This was America-in-motion, always humming, always watching.

I lay on my back staring at a ceiling I hadn’t memorized yet, thinking about how strange it was that peace didn’t feel warm. It felt neutral. Like a lake after a storm—no waves, no sparkle, just depth.

For forty years, my life had been defined by what I was holding together. The land. The memories. My son. Even after Margaret died, I told myself that holding on was the same thing as honoring. That endurance was love.

It took a legal ambush and a raised notary seal to teach me the difference.

The next morning I woke early out of habit and made coffee strong enough to wake the dead. I carried the mug out to the small back porch and sat down, listening. No loons. No wind through old pines. Just traffic in the distance and a dog barking three houses over.

I didn’t miss the lake the way I thought I would.

I missed who I was when I lived beside it.

A week later, the first letter arrived.

Not an email. A letter.

Thick paper. Law firm letterhead. New York address.

Michael’s former investors, it turned out, were not sentimental people. They were not inclined toward reflection or self-examination. They believed in leverage, consequences, and making examples.

James read the letter twice, then laughed.

“They’re fishing,” he said. “They always fish first.”

“They’re suing me?” I asked.

“They’re threatening to,” he corrected. “Big difference. They’re angry. They lost money they hadn’t finished counting yet.”

“And Michael?”

James’s smile faded. “Michael is radioactive right now. No firm wants him near a deal. They don’t trust his judgment.”

I nodded, absorbing that. Not with satisfaction. With a dull recognition.

That had always been Michael’s real flaw—not ambition, not success, not even greed. It was certainty. The belief that because something could be done, it should be done. That resistance meant ignorance, not disagreement.

A month passed.

Then another.

Spring came quietly that year. Trees budded. Lawns turned green. I learned my neighbors’ names. Learned which grocery store carried decent bread and which pharmacy didn’t lose prescriptions.

I volunteered twice a week at a local youth center—nothing official at first, just helping kids fix bikes, showing them how to tie knots, how to read a map without a screen telling you where you were. They called me “Mr. T,” which made me laugh more than it should have.

One afternoon, a boy asked me why I knew so much about the woods.

I told him the truth.

“Because I listened longer than most people do.”

He thought about that, then nodded, like it was something he might need later.

In May, the land trust invited me to attend the formal dedication of the property. A small ceremony. Local press. A county representative. Folding chairs set up near the trailhead.

I almost didn’t go.

Part of me wanted to let the place belong fully to itself now, without my shadow hanging over it like a ghost. But James insisted.

“You don’t vanish after a stand like that,” he said. “You show your face. You let it be known that you chose this.”

So I went.

The day was clear and bright, the kind of American spring day that looks good on camera. A banner hung between two posts: PRESERVED FOR FUTURE GENERATIONS.

Patricia spotted me immediately and came over, her face open, relieved, grateful in a way that still surprised me.

“You did something rare,” she said. “You gave without trying to control the ending.”

A local reporter asked me why I’d chosen preservation over development.

I thought about Michael’s face when he threatened me. About Margaret’s ashes. About the way money talks louder than memory in most rooms.

I said, “Because some places are already complete.”

That quote ended up in three regional outlets and one environmental blog. Nothing viral. Nothing loud.

Enough.

After that, the letters stopped.

The threats faded into legal static, then disappeared altogether. Investors found other projects. Other land. Other people to push.

Michael didn’t write again.

But I heard about him.

A mutual acquaintance—someone I hadn’t seen in years—ran into him at a professional networking event in Providence. He was thinner. Quieter. No ring on his finger.

“Still brilliant,” the acquaintance told me later. “But… humbled. Or close to it.”

I sat with that word for a long time.

Humbled.

Not broken. Not punished.

Just forced to stand somewhere without leverage.

In July, I drove up to the lake again. Not as an owner. As a visitor.

I parked in the lot, paid the small suggested donation, and walked the trail like everyone else. Families passed me—kids arguing about snacks, parents checking phones, laughter cutting through the trees.

No one knew who I was.

That was the best part.

I stood by the water where the dock used to be and watched dragonflies skim the surface. The lake didn’t recognize me either. It didn’t owe me nostalgia. It just existed, patient and indifferent and alive.

For the first time, I felt gratitude without grief attached to it.

Later that afternoon, I noticed a man standing a little apart from the crowd. Tall. Familiar posture. Hands shoved deep into his jacket pockets like he was bracing himself against something invisible.

Michael.

He hadn’t seen me yet.

He looked older. Not aged—worn. The way people do when the future stops being abstract and starts asking questions back.

I could have left.

I didn’t.

I stepped closer. Not fast. Not slow. Just enough.

“Michael,” I said.

He turned.

For a moment, he looked like he’d seen a ghost.

Then his face closed, instinctively, the way it always did when control slipped.

“Dad,” he said.

We stood there, the lake between us, the past humming like static.

“I didn’t know you’d be here,” he added.

“I didn’t know you would,” I said.

Silence again. Different this time. Less sharp.

“I came to see it,” he said finally. “What you… did.”

I nodded.

“I thought I’d be angry,” he continued, staring at the water. “But I’m just tired.”

I waited.

“I lost everything,” he said. “The firm. The network. Clare. The version of myself that knew what came next.”

“I know,” I said.

He flinched slightly, like he hadn’t expected empathy.

“I blamed you for a long time,” he said. “Still do, some days.”

“That’s fair,” I said.

He looked at me then, really looked, like he was searching for the trick, the angle, the defense.

“There isn’t one,” I said quietly. “I didn’t do it to hurt you.”

“I know,” he said. “That’s the worst part.”

We stood there while a family passed behind us, children running ahead, parents calling them back.

“I thought success meant never having to ask permission,” Michael said. “Never being told no.”

“And now?” I asked.

“And now,” he said, “I realize no one ever told me what it cost.”

I let that sit.

“I don’t know how to fix this,” he said. “Us.”

“You don’t fix it,” I said. “You live honestly long enough that it changes shape on its own.”

He nodded slowly.

“I don’t expect forgiveness,” he added.

“I’m not offering absolution,” I said. “I’m offering distance without hatred.”

That seemed to land.

We didn’t hug. We didn’t reconcile. There was no swelling music, no cinematic closure.

Just two men standing by a lake that belonged to neither of us anymore.

Before he left, Michael said, “You were right about one thing.”

“What’s that?”

“Some things shouldn’t be optimized.”

I watched him walk back toward the parking lot, shoulders a little less squared than they used to be.

I stayed until sunset.

That night, back in my small house, I slept deeply for the first time in years.

Not because everything was resolved.

But because nothing was pretending anymore.

Life didn’t give me back my son. Not fully.

It gave me something quieter, harder to explain.

Integrity without witnesses. Peace without applause.

And the understanding that sometimes, the bravest thing an American father can do isn’t to build an empire or leave an inheritance—

It’s to draw a line and refuse to sell the ground beneath his feet.

Autumn returned the way it always does in this country—without asking permission.

One morning the air sharpened, the sky turned a harder blue, and suddenly every tree on my street looked like it was preparing to leave. I noticed it while raking the small patch of yard behind my house, the sound of leaves scraping concrete oddly soothing. There was a time when that sound meant winterizing docks and checking storm windows at the cottage. Now it meant compost bags and city pickup schedules.

Life had narrowed.

And somehow, that made it clearer.

I fell into a rhythm. Tuesdays and Thursdays at the youth center. Saturdays volunteering with a local conservation group—trail maintenance, invasive species removal, the unglamorous work that never makes brochures. I liked that no one there knew my history. I was just another retired guy with decent knees and patience.

One Saturday, while hauling brush, a woman beside me asked what I used to do.

“I was a park ranger,” I said.

She smiled. “Figures. You walk like someone who trusts the ground.”

That stayed with me.

In October, Patricia called.

“We’ve had an anonymous donor fund a new education program,” she said. “Nature access for low-income schools. Transportation, gear, everything.”

“That’s good,” I said.

She hesitated. “The donor requested we name the scholarship.”

I stopped raking leaves.

“They want to call it the Margaret Thornton Program,” she said gently.

I sat down on the porch steps and let the phone rest against my ear while the past rose up without warning—Margaret laughing at nothing, Margaret scolding me for tracking mud, Margaret standing ankle-deep in the lake like it was a prayer.

“She would’ve liked that,” I said finally.

“I think so too,” Patricia replied.

The first group came in November.

Kids from a city district where trees were something you passed on the way to somewhere else. They arrived loud and restless and suspicious of quiet. I watched from a distance as volunteers handed out boots and jackets, as instructors showed them how to hold binoculars, how to listen.

One boy tugged on my sleeve.

“Mister,” he said, “is it always this quiet?”

“No,” I said. “But it’s always listening.”

He frowned, like that was a trick answer, then wandered off.

Later, I saw him kneeling by the water, whispering something I couldn’t hear.

That night, I went home and poured myself a drink—just one—and raised the glass to an empty chair.

“To promises kept,” I said.

December came with snow and early darkness. Holiday lights went up. My neighbors exchanged cookies. Someone invited me to a small Christmas dinner. I went. It was warm and awkward and human.

Michael didn’t call.

I didn’t expect him to.

On Christmas Eve, I received a text.

Just four words.

“I’m in therapy. Trying.”

I stared at the screen for a long time.

Then I typed back:

“That’s a start.”

Nothing else came.

That was enough.

The following spring, the lake flooded slightly—natural, seasonal. The trust posted notices explaining shoreline changes, educating visitors. No panic. No lawsuits. No rushed fixes.

I drove up again one quiet weekday morning. Walked the trail alone. Stopped where the old dock used to be.

A young couple stood there, holding hands, looking out at the water like it was a future.

I overheard the woman say, “I’m glad they saved this place.”

I kept walking.

At the far end of the trail, there’s a bench now. Simple. Wood. A small plaque.

For those who chose restraint.

No names.

I sat there until my knees complained and the wind picked up.

I thought about audits and assessments. About how easily we confuse value with price. About how this country loves winners, but rarely asks what winning costs.

Michael used to believe life was a ladder.

I’ve learned it’s a shoreline.

You can build on it. You can sell it. Or you can protect it long enough for someone else to stand there one day and feel less alone.

I don’t know what kind of man my son will become next.

That’s no longer my project.

What I do know is this:

Somewhere in America, a lake still reflects the sky exactly as it did seventy years ago.

Children will grow up believing that’s normal.

That quiet places don’t need to justify themselves.

And when my name eventually fades—when no one remembers who owned what or who signed which papers—

that lake won’t care.

That’s how I know I made the right decision.

Not because I won.

But because nothing that mattered lost.

News

I looked my father straight in the eye and warned him: ” One more word from my stepmother about my money, and there would be no more polite conversations. I would deal with her myself-clearly explaining her boundaries and why my money is not hers. Do you understand?”

The knife wasn’t in my hand. It was in Linda’s voice—soft as steamed milk, sweet enough to pass for love—when…

He said, “why pay for daycare when mom’s sitting here free?” I packed my bags then called my lawyer.

The knife didn’t slip. My hands did. One second I was slicing onions over a cutting board that wasn’t mine,…

“My family kicked my 16-year-old out of Christmas. Dinner. Said ‘no room’ at the table. She drove home alone. Spent Christmas in an empty house. I was working a double shift in the er. The next morning O taped a letter to their door. When they read it, they started…”

The ER smelled like antiseptic and burnt coffee, and somewhere down the hall a child was crying the kind of…

At my daughter’s wedding, her husband leaned over and whispered something in her ear. Without warning, she turned to me and slapped my face hard enough to make the room go still. But instead of tears, I let out a quiet laugh and said, “now I know”. She went pale, her smile faltering. She never expected what I’d reveal next…

The slap sounded like a firecracker inside a church—sharp, bright, impossible to pretend you didn’t hear. Two hundred wedding guests…

We Kicked Our Son Out, Then Demanded His House for His Brother-The Same Brother Who Cheated with His Wife. But He Filed for Divorce, Exposed the S Tapes to Her Family, Called the Cops… And Left Us Crying on His Lawn.

The first time my son looked at me like I was a stranger, it was under the harsh porch light…

My sister forced me to babysit-even though I’d planned this trip for months. When I said no, she snapped, “helping family is too hard for you now?” mom ordered me to cancel. Dad called me selfish. I didn’t argue. I went on my trip. When I came home. I froze at what I saw.my sister crossed a line she couldn’t uncross.

A siren wailed somewhere down the street as I slid my key into the lock—and for a split second, I…

End of content

No more pages to load