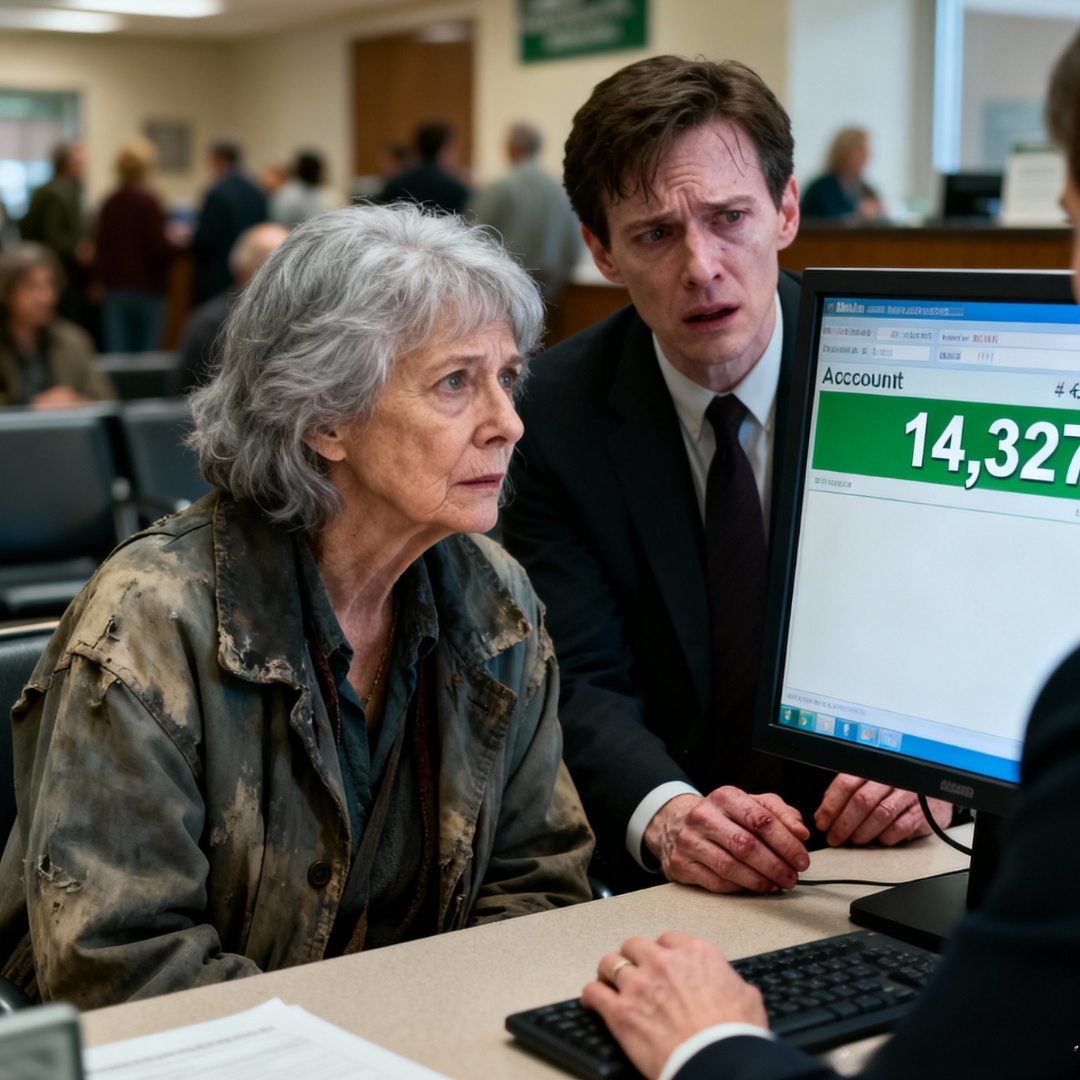

The bank manager’s face went the color of copy paper the second my balance popped up on his screen.

People think that’s an exaggeration when I tell it later, but I was a fourth grade teacher in Boston for 34 years. I know what someone looks like right before they faint. His hands actually trembled when he turned the monitor toward me, spinning it so I could see the numbers on the glowing screen in that quiet little branch off Boylston Street.

“Mrs. Sullivan,” he said, his voice doing a strange little wobble, “there… there must be some mistake.”

There wasn’t.

Not after everything I’d already lost.

Not after being called confused, unstable, senile—all those polite American words people use when they’re really saying, “We’ve decided not to believe you.”

Not after being betrayed by my own son.

But I’m getting ahead of myself.

My name is Dorothy Sullivan, though everyone calls me Dot. I’m 67 years old, born and raised in Massachusetts, with a Boston accent that still comes out when I’m tired or mad. I used to stand in front of a blackboard in Dorchester and teach kids how to multiply fractions and diagram sentences. I’ve said the Pledge of Allegiance with thousands of little voices over the decades. I’ve broken up more playground arguments than I can count. I’ve watched children who came into my classroom barely able to read leave talking about college and careers and “when I grow up.”

For most of my life, I thought I’d done okay. My late husband, Patrick, and I raised two kids in a modest three–bedroom colonial on a tree–lined street. Vinyl siding, flag on the porch, the kind of house you see in every American movie about “a good life.” We had a backyard with a grill and a plastic kiddie pool that lived there every summer for ten years straight. We took the kids to Cape Cod when we could afford it, packed sandwiches in a cooler, and parked three blocks away to avoid beach parking fees.

We weren’t rich.

We were comfortable.

We were happy.

Then pancreatic cancer came for Patrick.

Watching the man you love slowly shrink inside his own skin is a kind of horror no one prepares you for. Eight months of doctors and tests and chemotherapy that made his hands shake when he tried to hold his coffee mug. Eight months of watching a big, loud Irish–American man who could fix anything in the house suddenly not have the strength to open a jar of peanut butter.

He fought. Oh, he fought. Right up to the end, he worried about me and the kids more than himself.

His last words to me in that white, humming hospital room at Mass General were, “I made sure you’ll be okay, Dot. I promise.”

I held his hand until it went still and believed him.

At the time, I thought he meant the obvious things: the life insurance policy, the house we’d paid off by being boring and responsible, the savings we’d built by skipping fancy dinners and driving our cars until they rattled.

I had no idea just how right he’d been.

After the funeral and the casseroles and the endless parade of people saying “if you need anything,” life shrank. The house felt too big. The bed felt too cold. The mornings came too early. So I threw myself into my last years of teaching.

If you want to know what keeps a widow breathing after she loses her husband, I can tell you: thirty–two kids who need you to explain long division.

The kids kept me going. They still needed my math songs and my “teacher look” and the way I’d slip an extra snack into a backpack when I knew there wasn’t much food at home. But after two more years, my knees started to complain more loudly than my class. Getting up at 5:30 a.m. in the dark New England winter to scrape ice off the windshield lost its modest charm. At 65, I finally let myself retire.

I had a plan. I’m a teacher. Of course I had a plan.

I’d travel a little, maybe finally take that trip to Ireland Patrick and I always talked about. See where his grandparents were from, walk down some narrow street in Dublin muttering about the price of coffee in euros instead of dollars. I’d volunteer at the library. I’d babysit my grandkids so my daughter and son–in–law could go on dates. I’d join one of those senior groups that goes to matinee movies on Tuesdays.

On paper, everything looked good. The Dorchester house was worth about $450,000. We’d paid it off years earlier. We had savings of around $380,000. Patrick’s life insurance had paid out, and I’d been careful with it, treating it as sacred money, not a lottery. I had Social Security. I had my teacher’s pension. Nothing fancy, but enough that I didn’t have to worry about choosing between heat and groceries like some of the parents of my students did.

My son Kevin liked to call that “old–fashioned thinking.”

Kevin was always ambitious. Even as a boy he wanted the biggest slice of cake, the front seat of the car, the lead in the school play. He’s handsome—the kind of tall, dark–haired, quick–smiling man people in suits in downtown Boston shake hands with and say, “Let’s grab lunch sometime.” He went into real estate development, that glittering world of glossy brochures and “up–and–coming neighborhoods” and cocktail parties with developers from New York.

He partnered with a certified public accountant named Marcus Chen, a quiet man with an expensive watch and a calm, very sure way of talking about returns and projections. Together they bought distressed properties around the Boston area, fixed them up, broke their backs in Quincy and Revere and East Boston, and flipped them for profit.

Kevin called me every week, telling me about his latest deal, the next big project.

“Ma, I’m building something here,” he’d say, his voice full of that buzzing, dangerous energy I’d always loved and feared in him. “A real legacy. We’re going to be in the Boston Globe real estate section one day. You’ll see.”

I was proud of him. Of course I was. That’s what mothers do. We see the best even when the rest is waving flags.

My daughter Rachel is different. Softer in some ways, harder in others. She’s a nurse at Mass General, like the ones who held my hand when Patrick was sick. She married a kind man named Tom, a software engineer who wears flannel shirts and washes the dishes without being asked. They live in Cambridge in a modest condo, two kids, a Subaru in the parking lot. Rachel is the worrier of the family.

“Mom, are you sure you’re okay living alone?” she’d ask, looking around the house with a nurse’s eye—at the stairs, the throw rugs, the way the mailbox was a walk down the driveway. “Maybe you should think about a condo, less to take care of, fewer stairs. Or assisted living. One of the nice ones with exercise classes and book clubs.”

“I’m not ready to be old yet,” I’d say, swatting her with a dish towel. “Besides, this house is full of your father.”

She’d sigh but let it go. For the moment.

About eighteen months after I retired, Kevin showed up at my kitchen table with a proposition.

“Ma, you know I love you, right?” he started.

That’s always how trouble begins—with a reminder.

He sat in Patrick’s old chair, the sunshine slanting through the lace curtains, catching the little flecks of dust in the air. It was the same table where Patrick and I had eaten breakfast together for 33 years, where we’d laid out science fair projects and birthday cakes and bills that made my stomach clench.

“That house is too much for you,” Kevin said, looking around like a realtor, not a son. “Three bedrooms, that yard, the stairs. And honestly, Ma, Dorchester’s not what it used to be. There was a story on the local news last week about car break–ins two streets over. I worry about you.”

“I’m fine,” I said, a little sharper than I meant to. “I’ve lived here for forty years.”

“Right. But you could be more than fine.” He leaned forward, his voice dropping into that confidential tone he used when he shared business secrets. “Listen. I’ve got this great investment opportunity. Multi–family renovation in Quincy. Six units. Great location. The returns are incredible. And I was thinking… what if you came in as a partner?”

He laid it out like a teacher presenting a lesson. Use the equity from the house, plus some of my savings. Roll it into his project. They’d get me a nice condo—“Something modern, Ma, with an elevator, no shoveling snow, maybe in Cambridge near Rachel so she stops nagging you”—and my money would be “working for me instead of just sitting in the bank.”

“I don’t know, honey,” I said. Deal or no deal, that house was everything Patrick and I had built. Every leaky faucet he’d fixed, every inch of wallpaper we’d peeled and replaced. “Your father and I worked our whole lives for this. It’s all tied up in the house.”

“Exactly.” He smiled, that wide Sullivan smile that could charm a room. “And he’d want it working for you, not just sitting there losing value to inflation. Marcus has all the numbers. It’s completely safe, Ma. Family business. You’d be a partner with your own son.”

He said it with such confidence, such warmth. And maybe I was lonelier than I wanted to admit. My days had gotten quiet since I left the classroom. The phone didn’t ring as much. The house was too big, the nights too long. Rachel had her own life, her own family. Kevin including me in his big plans felt like a hand reaching back to pull me along.

“Let me think about it,” I said.

Over the next few weeks, Kevin brought Marcus over several times. Marcus sat at the table with his laptop open, showing me spreadsheets, projected returns, pictures of the Quincy property. It all looked very impressive, very professional. There were charts and color–coded graphs. He talked about “cap rates” and “appreciation” and “leveraging assets.”

“Mrs. Sullivan,” Marcus said in his smooth, careful voice, “with all due respect, this is the smart move. Fixed income in retirement, that’s… that’s old thinking. That’s your parents’ generation, savings bonds and certificates of deposit. Your generation built wealth through assets. This is how you protect what Patrick left you. You’re just shifting one asset into a better one.”

Something about the way he said Patrick’s name made my stomach twist. Too casual, too practiced, like he’d used that line before. But I pushed the feeling aside.

Rachel was not pleased when I told her.

“Mom, that’s a lot of money,” she said, tugging her scrubs top over her head after a long shift. “Are you sure? I mean, Kevin’s done well, but this seems… risky. You worked your whole life for that house.”

“It’s his business, sweetie,” I said. “He knows what he’s doing. And he’s including me. He wants to take care of me.”

She chewed her lip, that old habit from childhood. “Just… be careful, okay? Maybe have a lawyer look at everything first.”

I should have.

I didn’t.

I trusted my son.

In March of 2024, I sat in a conference room with Kevin and Marcus and signed the papers they put in front of me. The title company agent slid documents across the table. There were so many pages it felt like signing my name into oblivion.

I sold the Dorchester house.

I moved into a small rental condo in Medford that Kevin said was “temporary.”

“Just until we close the deal and find you something better,” he promised.

I transferred $680,000—everything from the house and nearly all my savings—to an LLC Marcus had set up.

“It’s for liability protection,” he said. “Standard business practice. Keeps everyone safe.”

Kevin and Marcus were listed as managing partners.

I was listed as a passive investor.

The name “Dorothy Sullivan” looked small on that paperwork.

The first few months were fine. Kevin texted me photos of construction progress—demolition one week, new framing the next. He sent email updates full of percentages and timelines. I bought new curtains for the Medford place and told myself this was an adventure, that people all over America moved to condos at my age.

It wasn’t the Cambridge elevator building near Rachel he’d talked about. It was off a busy road near a strip mall and a Dunkin’ with a drive–thru, but it was okay. Loud. Tiny. But okay.

Then the updates slowed down.

Then they stopped.

When I called Kevin in September, I could hear noise in the background—voices, music, the clink of glasses.

“Ma, I’m in the middle of something,” he said. “Can I call you back?”

He didn’t call back.

In October, I drove to Quincy to see the property myself. It sat there, a big, tired three–family house with plywood over one window and weeds growing through the front walk. No trucks. No workers. No dumpsters. No sign of anything happening.

A chill ran down the back of my neck.

I called Marcus. His number was disconnected.

That’s when the fear really set in, heavy and cold.

I went to Kevin’s office downtown, in one of those refurbished brick buildings near the Financial District where everyone wears tailored coats and carries sleek laptops.

“I’m sorry, Mrs. Sullivan,” the receptionist said, looking like she wanted to be anywhere else. “Kevin isn’t in today.”

“When will he be in?” I asked.

She glanced at her screen, then away. “I’m not sure. You might… you might want to call him.”

I did.

Seventeen times that day.

No answer.

Finally, at eight o’clock that night, my phone rang. I grabbed it so fast I almost dropped it.

“Kevin?”

“Mom, it’s me,” Rachel said. “What is going on?”

My hands started shaking. “What do you mean? Have you talked to Kevin? Where is he?”

“I just got off the phone with him,” she said. “He said you’re confused. That you’ve been calling his office constantly, that you’re… harassing his staff. Mom, he sounds really worried. He says you’re having memory issues. That you’re mixing up paperwork. What’s going on?”

For a second, the room tilted.

“What?” I said. “Rachel, no. I’m trying to find out what happened to my money. To the investment. I gave Kevin and Marcus over six hundred thousand dollars. I signed papers. They set up an LLC. I have documents. Something’s wrong.”

“He says there is no investment,” she said, her voice cautious. “He says you signed over power of attorney for medical decisions and you’re mixing it up with some business thing you imagined. He thinks you might need to see a doctor, Mom. Maybe… maybe even consider assisted living, just until we figure out what’s happening.”

He was telling my daughter I was losing my mind.

He was telling people I was confused.

Gaslighting, they call it on TV dramas. I used to think that was a fancy word for arguments. It turns out it’s much colder than that.

“I am not confused,” I said. I could feel my pulse in my throat. “I gave him the money. I signed documents. I’ll show them to you.”

I marched to the metal filing cabinet in the corner of my bedroom. I pulled open the drawer where I’d carefully filed everything: tax returns, pension information, the folder with all the papers Kevin and Marcus had given me.

The folder wasn’t there.

I pulled everything out, paper fluttering to the floor. Receipts, old electric bills, my Social Security award letter. No LLC. No investment documents. No wire receipt.

“Mom?” Rachel said in my ear. “Can you find them?”

“They’re gone.” My voice sounded far away. “The papers are gone. But I know I signed them. I know I did.”

“Okay,” Rachel said softly. “Okay. Why don’t you come stay with Tom and me for a few days? We’ll figure this out together, okay? We’ll make an appointment with your doctor, just to rule things out.”

There was doubt in her voice. Not because she wanted to hurt me. Because it’s easier to believe your mother is confused than that your brother is a thief.

The next morning, I went to my bank. Not the one with the marble on Boylston where I’d someday walk into the vault, but my regular neighborhood bank in Medford, with its carpet that always smelled faintly of coffee and ink.

The savings account that had once held $380,000 showed a balance of $14,327.

I stared at the screen, thinking surely I was reading it wrong. Numbers blurred.

“That’s not possible,” I said. “There should be… there should be more. Much more.”

The manager, a kind woman in a blazer with the bank logo pinned to the lapel, pulled up the transaction history. “It looks like you’ve authorized a series of wire transfers over the past six months,” she said, frowning. “All to the same external account.”

“I didn’t authorize any wire transfers,” I said. “I never use wires. I don’t even know how.”

“These show electronic authorization using your online banking credentials,” she said gently. “And this receiving account… it was opened in your name.”

She showed me the signature card. The loops and lines looked like my handwriting, but not quite. The “D” in Dorothy slanted a little differently. The “S” in Sullivan was too smooth, like someone had practiced it. My stomach lurched.

Someone had forged my name.

I felt like I was drowning.

I called the police. A young officer came to my condo. He looked so young he could’ve been one of my former students grown up, his uniform too crisp.

He took notes, nodding, but there was something in his eyes I recognized from dealing with parents who thought their little angels never lied.

“Ma’am,” he said finally, “this sounds like a civil matter. A family dispute. You gave your son access to your accounts, you signed over the house proceeds. If you believe you were defrauded, you’ll need to hire an attorney. We can’t arrest someone for a business deal gone bad.”

“A business deal gone bad?” I repeated. “He stole my life.”

“I’m sorry,” he said, and I think he meant it. “But without clear proof of forgery or coercion, there’s not much we can do.”

I called lawyers. One quoted me a $35,000 retainer for elder fraud cases. Another wanted fifty. A third actually made a sympathetic noise and then said, “Mrs. Sullivan, cases like this are expensive. You’re looking at years of litigation, expert witnesses, forensic accountants. Without significant resources, I… can’t help you.”

Significant resources. I almost laughed. My “significant resources” were currently paying for my son’s lifestyle.

Desperate, I drove to Kevin’s house in Wellesley, one of those perfect Massachusetts suburbs with tree–lined streets and white–columned colonials. His house looked like something off a real estate postcard. The kind of place people in Ohio dream about when they picture “life on the East Coast.” Stone walkway, perfect lawn, two–car garage.

My money, I thought. In clapboard and shutters.

Amber, his wife, opened the door. Behind her, I could see my grandchildren peeking out—Emma with her curls, Noah clutching a toy truck, little Luke with yogurt on his shirt.

“Dorothy,” Amber said tightly. “Kevin’s not here.”

“When will he be back?” I asked. “I need to talk to him. This can’t wait, Amber. Please. It’s about the money—”

She sighed, and something flickered in her eyes. Pity. Or guilt. Or both.

“He said you might come by,” she said. “He said you’re… not well. That you’re having delusions. Dorothy, I’m sorry, but he doesn’t want you around the kids right now. Not until you get help.”

“Not well?” My voice rose. “Delusions? He stole from me. He emptied my accounts. He took the money from the house. He—”

“If you don’t leave,” she said, her voice shaking now, “I’ll have to call the police.”

She closed the door in my face. The latch clicking sounded like a slammed gavel.

Through the window, I saw Emma, seven years old, watching me with wide eyes as her mother pulled the curtain closed.

I went home to my little condo and sat in the dark. The refrigerator hummed. A car alarm went off somewhere outside and then stopped. I could hear my upstairs neighbor’s television, muffled laughter from a sitcom audience.

Everything Patrick and I had built was gone.

My son was gone.

My relationship with my grandchildren was gone.

I was 67 years old with $14,327 in the bank, $1,100 a month in Social Security, and rent I couldn’t afford past January. I started doing math the way I used to in front of a classroom, only this time the equation was: How long until I run out?

Somewhere in that long, awful night, I thought about not being here anymore. Not in the careful way where you plan, just in the desperate way where you imagine the quiet that would come if you stopped fighting. Patrick’s old medicine bottles were still in a shoebox in the back of my bathroom cabinet. I found myself looking at them too long.

Instead, I cried until my chest hurt and there was nothing left.

Then something else rose up.

Anger.

Teachers know this: there comes a point where you’ve been patient and understanding and flexible, and then something clicks and you say, “Enough.”

That next day, I started documenting.

I wrote down every conversation I could remember, every date Kevin had come over, every time Marcus had shown me a spreadsheet. I wrote about the phone calls, the bank visit, the forged signature. I wrote in block letters, my hand cramping. It felt like building a case for a science fair project, only the hypothesis this time was: My son stole from me.

I went to the county registry of deeds and requested copies of every document related to the sale of my house. It cost ten dollars a page. Money I couldn’t afford. I handed over the bills anyway.

What I found made my skin crawl.

The signature on the quitclaim deed transferring the Dorchester house to the LLC looked almost exactly like my handwriting. Almost. The “D” was wrong again. The notary stamp belonged to a man whose name I didn’t recognize. I looked him up later. He turned out to be Marcus’s brother–in–law.

The whole thing was rotten.

Knowing that and proving it are two different battles.

Rachel came to visit in early December. She brought grocery bags and a worried look.

“Mom,” she said, sitting across from me at the tiny Medford kitchen table, “I’ve been thinking. Maybe Kevin’s right. Maybe you should see a doctor. Just to rule things out.”

“You don’t believe me,” I said.

“I want to,” she said. “But you’re almost seventy. These things happen. Memory issues, confusion. It’s not your fault. You… might have signed something you don’t remember.”

“I am not confused,” I said, pulling my hands away from hers. “He stole everything. Your father’s life insurance. Our savings. Our home. Everything we built. And you’re telling me I’m… losing my mind?”

“That’s not what I’m saying,” she protested. “I’m saying there might be an explanation. Maybe—”

“Get out,” I said. My voice surprised us both. It was the voice I used in class when a kid threw something. “If you won’t believe me, if you won’t help me, then leave.”

She left crying.

I sat in the dark again, wondering if everyone I loved thought I was crazy.

Wondering if maybe they were right.

Christmas came and went like a commercial on TV. I spent it alone with canned soup and old black–and–white movies on some classic channel, pretending the laughter from studio audiences was real company. No calls from Kevin. No calls from Rachel. No grandkids jumping on my lap. The phone stayed still on the counter like a stone.

On December 28th, the eviction notice arrived. Official letterhead. Legal language. The rent was past due. I had until January 31st to vacate.

I stood in the doorway of that little condo—the bad carpet, the neighbor’s footsteps overhead, the constant noise from the street—and thought, I’m going to be homeless. In America. After 34 years of working in public schools, after a 43–year marriage, after paying my taxes on time every year, I was going to be sleeping in a shelter with my life in plastic bags.

I started looking up places to go on the free Wi–Fi at the public library. The woman behind the desk smiled at me like I was any other patron. She had no idea I was trying to Google “Boston women’s shelter intake.”

On January 15th, I was packing my few belongings into cardboard boxes I’d begged from the grocery store when I found it.

An old shoebox in the back of my closet, tucked behind winter boots I hadn’t worn in years. I must have thrown it in there when we moved from Dorchester, too tired to sort it.

Inside were photos. Birthday cards from 1998 with the kids’ handwriting. A dried corsage from some long–ago wedding. And an envelope.

My name was on the front in Patrick’s handwriting.

“For Dot. Emergency only.”

My hands shook as I slid a finger under the flap.

Inside was a small metal key and a letter.

My dearest Dot, it began. If you’re reading this, something has gone terribly wrong, and I’m not there to help you. I’m sorry. I’m so, so sorry.

I had to stop because the words blurred.

He wrote about the day we got his diagnosis, the way my face had gone white, how he’d lain awake nights thinking about what would happen to me if he went first. He wrote about how he’d watched couples in the hospital cafeteria, the ones where the sick spouse worried more about the healthy one than themselves.

“You know about the life insurance policy,” he wrote. “We talked about that. What you don’t know is that I’d been preparing in other ways, too. Not because I didn’t trust you or the kids, but because life is uncertain, and I wanted to make absolutely sure you’d be protected.”

He explained about the key. It was for a safety deposit box at Boston Private Bank on Boylston Street. Box number 447. It was in both our names. He’d kept up the fees, even when he was in the hospital. “The last payment is good through 2030,” he wrote, and I could see him, sitting at the kitchen table with a calendar and a checkbook, planning for a future he wouldn’t see.

“Inside you’ll find U.S. savings bonds,” he wrote. “I bought them slowly over 20 years. They should be worth about $95,000 now, maybe more.”

I gripped the page tighter.

“Stock certificates,” he continued. “When my father died in 1998, I inherited 800 shares of Johnson & Johnson. I never sold them, just kept them in the box. I don’t know what they’re worth now, but hold on to them. Let them grow if you don’t need them.”

“Your grandmother’s jewelry is in there too. Not much, but the rings are real gold, and there’s an emerald necklace that might be worth something.”

“At the very bottom there’s another letter,” he finished. “Read it if you need strength. It’s from the man who loved you more than life itself. Dot, I don’t know what emergency brought you to this letter, but whatever it is, you’re strong enough to handle it. You’re the strongest person I’ve ever known. You raised our children. You dealt with my mother for forty years. You held my hand while I died and didn’t let me see how scared you were. You’re going to be okay. I made sure of it. All my love, always and forever, Patrick.”

I pressed the letter to my chest and sobbed so hard I thought I might break.

Five years in the ground, and Patrick was still taking care of me.

The next morning, I put on my best coat—the one I used to wear to parent–teacher nights—and took the bus into downtown Boston. I walked past the Public Garden, bare winter trees reaching into a gray sky, past tourists bundled in coats, past the glass and stone of Back Bay office towers.

Boston Private Bank loomed ahead, all marble floors and brass fixtures, the air smelling faintly of polish and old money. It was the kind of place I’d always assumed was for other people. Wealthy people from Beacon Hill and the Back Bay, not retired schoolteachers from Dorchester.

“I need to access a safety deposit box,” I told the woman at the front desk, trying to keep my voice steady. “Box 447. It should be under Patrick and Dorothy Sullivan.”

She typed my name into the computer, checked my ID, and nodded. “Yes, Mrs. Sullivan. Right this way.”

The vault was exactly what you’d imagine from a movie—heavy door, thick walls, quiet that felt heavy. She slid Box 447 out of its slot and carried it into a small private room, setting it on the table.

“I’ll leave you alone,” she said, and closed the door behind her.

My hands shook as I turned the key.

The lid came up with a soft metallic scrape.

Everything Patrick had promised was there. Neatly stacked U.S. savings bonds, each labeled in his precise, blocky handwriting. Series EE bonds bought between 1990 and 2010.

I counted them. The face value totaled $50,000. When I checked the current value on my phone later, the total came to $96,300.

The stock certificates were in a manila envelope. Johnson & Johnson. Eight hundred shares. I typed the ticker into my phone. Current price: around $156 a share.

$124,800.

My breath caught.

The jewelry was in a small velvet bag—his grandmother’s emerald necklace, the two gold rings, a pearl bracelet. I’d seen them in an old black–and–white photo of his grandmother standing in front of a church somewhere in South Boston in the 1940s, pearl choker around her neck, proud Irish eyes staring straight into the lens.

At the bottom of the box was the second letter.

My Dot, it began.

If you’ve made it to the second letter, things must be really bad. I’m sorry I’m not there. I’m sorry for whatever has happened. I want you to know some things.

First, you are not crazy. You are not confused. You are not weak. You are brilliant and capable, and if someone has hurt you or taken advantage of you, it is not your fault. Do you hear me? Not your fault.

Second, use this money to fight. Hire the best help you can find. Get justice. You deserve justice.

Third, remember that time in 1987 when I lost my job at the factory and you held us together? You worked those double shifts waitressing. You made sure the kids never knew how worried we were. You told me, “Patrick Sullivan, we are not quitters. We figure it out.”

Well, I’m telling you now, Dorothy Sullivan, you are not a quitter. You will figure this out.

Fourth, and this is important. Whatever has happened, whatever you’re facing, remember that you are loved. I loved you. Our marriage was the best 43 years of my life. If our children can’t see what an amazing woman you are, that’s their failure, not yours.

You gave me everything, Dot. You gave me a home, a family, a reason to fight when the cancer tried to take me early. You held my hand when I was dying and told me it was okay to let go. You gave me peace.

Now I’m giving you this. Not money.

Freedom.

Freedom to fight back. Freedom to stand tall. Freedom to show whoever hurt you that Dorothy Sullivan is nobody’s victim.

I love you. I believe in you. And I’m watching over you.

Always yours, Patrick.

I sat in that tiny room in the vault and cried until I couldn’t breathe. Then I wiped my face, folded the letters carefully back into the box, and told Patrick out loud, “Okay. Let’s fight.”

I left the jewelry in the safety deposit box. I took the bonds and the stock certificates with me, tucked into my bag like they were made of glass.

Back in the January cold, with the wind coming off the Charles and tourists snapping pictures of brownstones, I found a bench and pulled out my phone. I searched for lawyers again.

This time, I looked for something different.

“Elder financial exploitation attorney Boston sliding scale,” I typed.

One name popped up on multiple sites, with reviews that made my chest loosen a little.

Sarah Chen.

No relation to Marcus, as she would later clarify with a wry smile.

She ran a small practice in Chinatown, above a bakery that smelled like sugar and coffee. Her website had a picture of her standing in front of a bookshelf, no fancy slogans, just a simple line: “Advocating for seniors and their families.”

When I called, she didn’t ask for a retainer amount first.

“Mrs. Sullivan,” she said after listening to my story, “I charge a sliding scale based on ability to pay for elder fraud cases. If your facts are as clear–cut as they sound, I’ll work on contingency. I get thirty percent if we win. If we lose, you pay nothing except court costs. Can you come in tomorrow?”

“I can come in today,” I said.

Her office was small but neat. Her hair was streaked with gray, pulled back in a ponytail. Her suit jacket was draped over the back of her chair, sleeves rolled up over strong, capable hands.

She spent two hours going through my documentation, Patrick’s letters, the bonds and stock certificates, the county records, the bank printouts. She didn’t talk much. She just read, occasionally asking a question and jotting down notes in a careful hand.

Finally, she closed the last folder.

“Mrs. Sullivan,” she said, “you have an excellent case. This is textbook elder financial exploitation.”

She ticked off the points like a checklist: the forged signatures, the fake LLC, the wire transfers, the isolation tactics, the way Kevin tried to paint me as mentally unstable.

“We can prove all of it,” she said. “But I need to be straight with you. This will take time. Probably a year, maybe more. And it will be hard. Your son will fight back. He will say you’re confused, that you’re misremembering. He’ll try to drag your reputation through the mud. Are you prepared for that?”

I thought of standing in front of a class of thirty kids with a broken air conditioner in June and a principal telling me I wasn’t differentiating instruction enough. I thought of raising two kids on a teacher’s salary. I thought of watching Patrick die.

“I’ve been preparing my whole life,” I said. “My son doesn’t scare me anymore.”

Sarah smiled, a small, fierce curve of her mouth.

“Then let’s get started,” she said.

The first thing she did was file for a formal competency evaluation. If Kevin wanted to call me confused, we’d let an expert weigh in.

A psychiatrist spent three hours with me. We did memory tests, recall exercises, logic puzzles, orientation questions. He asked about my day–to–day life, my routines, my bills. He asked me to remember lists of words and draw a clock.

The report came back: no signs of dementia, cognitive impairment, or memory loss. Alert, oriented, articulate. Full capacity.

We filed a civil suit against Kevin and Marcus for fraud, elder abuse, forgery, and theft by deception. We filed criminal complaints with the district attorney’s office. We hired a forensic document examiner who analyzed my signatures on file—driver’s license, mortgage documents, old bank signature cards—and compared them to the ones on the forged deed and bank account.

He testified, on paper first and later in person, that the signatures on the Saul–over deed and signature card were not mine. “They show signs of tracing and simulation,” he wrote. “In my expert opinion, they are forgeries.”

We subpoenaed bank records, company records, emails.

Kevin fought back hard.

His lawyer, a slick man from a big downtown firm with cufflinks that probably cost more than my first car, filed motions arguing that I had willingly transferred my assets to Kevin as part of “estate planning.” He claimed I’d given him broad power of attorney. He suggested I was now experiencing “regret” and trying to blame my son for my own decisions.

He submitted a statement saying I’d shown signs of confusion for years. That Rachel had expressed concerns about my memory.

That one hurt the most.

Sarah was relentless. She tracked down Marcus. She found three other elderly clients Kevin had “invested for,” all with eerily similar stories—houses sold, money transferred to LLCs, vague promises, then silence and empty accounts.

They joined our suit.

In March, Rachel called.

“Mom,” she said, her voice breaking, “I’m sorry. I’m so, so sorry.”

“What happened?” I asked, my stomach tightening.

“I read the court filings,” she said. “Sarah sent me copies. The forensic reports. The bank records. I… I can’t believe…”

Her words stuttered into silence.

“I should have believed you,” she whispered.

“Why didn’t you?” I asked, and there it was, the raw pain in my chest finding voice.

“Because he’s my brother,” she said. “Because I couldn’t imagine he’d do something like that. Because it was easier to believe you were confused than to believe he was capable of that. Mom, I was wrong. I’m so sorry. Please tell me how I can help.”

“I need you to testify,” I said. “About the phone call where he told you I was confused, where he tried to convince you I needed ‘help’ instead of help. Can you do that?”

“Yes,” she said. “Whatever you need.”

The trial was set for August in a courtroom in downtown Boston, the kind of place I’d walked past a hundred times without imagining I’d ever be inside as anything but a tourist.

Kevin arrived in an expensive suit. He still had that Sullivan posture, back straight, jaw set, like he was walking into a business meeting. He barely looked at me.

Sarah laid out our case like a story. She started with the timeline—the retirement, the pitch at my kitchen table, the sale of the Dorchester house, the transfer of funds to the LLC. She moved through the empty Quincy property, the disconnected phone, the forged signatures, the fake account.

She brought in the other victims. They told their stories from the witness stand, their voices shaking. A seventy–two–year–old man from Revere. A widow from East Boston. A retired postal worker. Each had trusted Kevin with everything they had. Each had been called confused when they asked where their money went.

Rachel testified. She talked about the night Kevin called her, his calm voice, his “concern” about my mental state. She cried on the stand, makeup smudged, and said in front of the judge and the jury, “I chose to believe my brother over my mother, and I was wrong. She was telling the truth. I ignored it. I will regret that for the rest of my life.”

The turning point came when Sarah called Marcus.

Kevin’s lawyer tried to keep him off the stand. He argued about privilege and prejudice and procedural nonsense. The judge, a woman with sharp eyes and no patience for theatrics, listened for a bit and then ruled that Marcus would testify.

Under oath, with the threat of perjury hanging over him, Marcus cracked.

He admitted Kevin had pressured him to set up the fake LLC. That he’d forged my signature on some documents and watched Kevin trace it on others. That Kevin had joked, “Why wait for an inheritance when you can arrange your own?” He said Kevin told him I was “old–school” and “wouldn’t understand” modern investing.

He said Kevin had threatened to expose some irregularities in Marcus’s own accounting business if he didn’t help.

“I was wrong,” Marcus said finally, looking down at his hands. “I was wrong, and I’m sorry.”

The jury was out for four hours.

When they came back, the foreperson—a woman in her fifties, with the kind of sensible haircut I’d seen on a thousand PTA moms—stood up and, in that quiet Boston courtroom, said the words that changed everything.

Liable.

Liable for fraud. Liable for elder abuse. Liable for conversion of assets.

The judge ordered Kevin to return all the money he’d taken from me—the house proceeds, the savings, everything—plus punitive damages of $200,000. She also ordered restitution for the other victims.

But it didn’t stop there.

The district attorney’s office, having watched the civil case unfold like a slow train wreck, filed criminal charges. Elder abuse. Fraud. Forgery. Theft.

One crisp November morning, while the leaves in the Boston Commons turned orange and tourists lined up for pumpkin spice coffee, Kevin Sullivan was arrested. He made bail, of course. He always landed on his feet.

Except this time, the ground had shifted.

His business collapsed. Clients fled. Marcus pled guilty to conspiracy and fraud, trading his cooperation for a lighter sentence. His CPA license was revoked. He went to prison for two years.

Kevin’s trial was scheduled for March. He was facing real time.

I should have felt triumphant. Vindicated.

Mostly, I felt hollow.

In December, before the criminal trial began, I asked Sarah if I could see him. There was a no–contact order regarding the case, but she said if we didn’t talk about the proceedings, if it was just… mother and son… she couldn’t stop me.

He was living in a small apartment in Quincy by then. Gone were the Wellesley columns. Gone was the polished hardwood. The building was a tired three–story walk–up near the T.

He opened the door slowly.

He looked twenty years older than his forty–one years. Dark circles under his eyes. Hair thinner. Shoulders slumped.

“What do you want?” he asked dully.

“To talk,” I said.

“I’m not supposed to have contact with you,” he said. “Court order.”

“This isn’t about the case,” I said. “This is about us.”

He hesitated, then stepped back. I walked in.

The apartment was sparsely furnished. A couch, a small TV, a cluttered coffee table. No pictures on the walls. It smelled faintly of takeout and something like despair.

We sat in silence for a minute. I could hear distant traffic, the hum of a neighbor’s TV through the wall.

“Why?” I asked finally. “Why did you do it?”

He stared at his hands.

“I was drowning,” he said quietly. “The business… it wasn’t going like I said. I made bad investments. I had… other problems.”

He didn’t say the word, but I’d seen enough documentaries to know what he meant. Gambling. Maybe worse.

“I was in debt to some very bad people, Mom,” he said. “I was desperate.”

“So you stole from me,” I said. “From your mother.”

“I told myself it was temporary,” he said, voice cracking. “That I’d pay you back once I got back on my feet. That I was just… borrowing my inheritance early. Then it got bigger. The lies. The pressure. Marcus kept saying we could make it up on the next deal. And when you started asking questions… I panicked. I thought if I could convince everyone you were confused, if… if I could get you declared incompetent, you’d stop. You’d just… let it go.”

“You tried to have me declared incompetent,” I said quietly. Saying it out loud made the room feel colder.

He put his head in his hands.

“I know,” he whispered. “I know. I’m sorry. I’m so sorry. I don’t expect you to forgive me. I don’t deserve it.”

I looked at him. Really looked at him.

I saw my son. My baby boy who’d once fallen asleep on my chest, warm and heavy. The seven–year–old who’d walked into my classroom on “Bring Your Kid to Work Day” and announced to my students that his mom was the best teacher in Boston. The teenager who’d yelled “I hate you!” when I grounded him and then cried in my arms an hour later.

I also saw the man who had signed my name on lies.

“You’re right,” I said. “You don’t deserve forgiveness. You stole my home, my security, my dignity. You tried to convince everyone I was losing my mind. You kept me from my grandchildren. You betrayed everything your father and I taught you.”

He nodded, tears sliding down his face.

“But I’m going to forgive you anyway,” I said.

He looked up, startled.

“Not because you deserve it,” I added quickly. “Because I deserve peace. Because holding on to this hate is destroying me. Because your father would want me to. Not for your sake, Kevin. For mine.”

“Dad would hate me for what I did to you,” he said.

“Yes,” I said. “He would. He’d be furious. He’d also tell you that people can change. That who we are isn’t defined solely by our worst moment, but by what we do after it.”

“How?” he asked, hoarse. “How do I come back from this? I’ve lost everything. My business. My marriage. The kids barely talk to me. I’m probably going to prison. How do I fix that?”

“You don’t fix it,” I said. “You accept it. You go to prison. You serve your time. You get help for the things that made you capable of this. You work on yourself every day. And maybe, someday far in the future, you become a man your father would be proud of again. But that’s on you. I can forgive you. I can’t rebuild you.”

“I don’t deserve your forgiveness,” he said again.

“No,” I said. “You don’t. But I’m your mother. And I’m tired of carrying this anger. So I’m putting it down.”

I stood to leave. He followed me to the door.

“Mom,” he said. “Thank you. For everything you did for me growing up. I’m… I’m sorry I forgot. I’m sorry I threw it away.”

“So am I,” I said. “So am I.”

I haven’t seen him since.

Rachel and I are stitching ourselves back together slowly. She brings her kids to visit at my new place. We bake cookies. We read stories. They know something happened with Uncle Kevin, but they only know that Grandma went to court to make something right.

Amber won’t let me see Kevin’s children. I understand. Maybe someday, when they’re older and can decide for themselves if they want to know the woman their father tried to erase.

With the settlement money, I bought a small house in Quincy. Nothing fancy. Two bedrooms, a little yard, a porch big enough for a rocking chair. It’s mine. No one else’s name on the deed. Every time I pay the property tax bill, I smile a little. It feels like a quiet victory.

I used some of the money to set up a fund at the local library—the Patrick Sullivan Reading Program—for kids who are falling behind. We offer free tutoring, summer reading clubs, and a quiet place to sit after school. The librarians joke that I’m there so much they should put me back on the payroll.

The rest I invested properly this time, with a fiduciary financial adviser Rachel researched and vetted. A woman who explains things slowly, with no pressure, who puts everything in writing and looks me in the eye when she talks about risk.

Three days a week, I volunteer at a legal aid clinic in Boston that helps seniors. I sit in a cramped office with a wobbly table and listen to stories that sound too familiar.

“My grandson borrowed my credit card and never gave it back.”

“My niece had me sign something and now I don’t own my own house.”

“My son says I’m confused, but I know I didn’t agree to this loan.”

I tell them, “You’re not alone. You’re not stupid for trusting family. You loved. That’s not a mistake. What they did with that trust is on them, not you.”

Sometimes, when the waiting room is full and the stories are heavy, I step outside and look up at the sky over Boston—the same sky that watched me walk out of a classroom for the last time, the same sky that saw my son in handcuffs, the same sky that arches over every house and apartment and shelter in this city.

Six months ago, on a clear late–summer morning, I drove to Revere Beach with a little tin box in my bag. I walked down to the water, the sand cool under my shoes, kids squealing in the surf, seagulls wheeling overhead. I opened the box.

Patrick’s ashes caught the sunlight for a second as the wind took them. I whispered, “Thank you. For loving me. For protecting me even after you were gone. For believing in me when I almost stopped believing in myself.”

The funny thing is, I am happier now than I was before everything fell apart.

Not because of the money. Because I know now that I can survive the worst thing I ever imagined and still get up in the morning and make coffee.

Some people ask me how I forgave Kevin.

The truth is, I forgave him for me, not for him.

I forgave him because Patrick’s letters reminded me who I am. I am Dorothy Sullivan from Dorchester, who is not a quitter. Who figures it out. Who survives.

Last week, I got a letter with a state correctional facility return address. Kevin’s handwriting on the front.

He’s serving eight years now.

The letter was five pages long, handwritten. He apologized again. He wrote about the classes he’s taking, the counseling. He wrote about thinking of his father when he’s tempted to feel sorry for himself. He wrote about trying, every day, to be someone better than the man who signed his mother’s name on lies.

“I don’t expect you to write back,” he wrote at the end. “I don’t expect anything. I just wanted you to know that I think about you every day. I think about Dad. About the man he was, the man he wanted me to be. I failed him. I failed you. But I’m going to keep trying to be better. Not for forgiveness. Just because it’s right.”

I sat at my kitchen table, the afternoon light slanting in, the hum of a lawnmower from next door, and I picked up a pen.

Kevin, I wrote.

Your father used to say who we are is defined not by our worst moments, but by what we do after them. Keep trying.

I’m proud you’re trying.

Love, Mom.

Because at the end of the day, he is still my son, and I am still his mother.

Maybe that still means something in this country where we put so much weight on self–reliance and “doing it on your own,” where we measure success in square footage and retirement accounts. Maybe forgiveness means understanding that people are complicated. That good people can do terrible things. That families can be messy and broken and still, somehow, worth something.

Or maybe it just means that, finally, I am at peace.

And somewhere, in a safety deposit box on Boylston Street, there are two letters from a man who made sure of that long before I knew I’d need it.

News

At thanksgiving dinner, my daughter-in-law claimed control of the family and shut off my cards. Everyone applauded. I smiled at my son and said one sentence that changed everything right there at dinner…

The cranberry sauce didn’t fall so much as surrender. One second it was balanced in Amber’s manicured fingers—ruby-dark, glossy, perfectly…

“They’re all busy,” my brother said. No one came. No calls. No goodbyes. I sat alone as my mother took her final breath. Then a nurse leaned in and whispered, “she knew they wouldn’t come… And… She left this only for you.

The first thing I noticed wasn’t the machines. It was the empty chairs. They sat like accusations in the dim…

My husband threw me out after believing his daughter’s lies three weeks later he asked if I’d reflected-instead I handed him divorce papers his daughter lost it

The first thing that hit the driveway wasn’t my sweater. It was our anniversary photo—spinning through cold air like a…

He shouted on Instagram live: “I’m breaking up with her right now and kicking her out!” then, while streaming, he tried to change the locks on my apartment. I calmly said, “entertainment for your followers.” eventually, building security escorted him out while still live-streaming, and his 12,000 followers watched as they explained he wasn’t even on the lease…

A screwdriver screamed against my deadbolt like a dentist drill, and on the other side of my door my boyfriend…

After my father, a renowned doctor, passed away, my husband said, “my mom and I will be taking half of the $4 million inheritance, lol.” I couldn’t help but burst into laughter- because they had no idea what was coming…

A week after my father was buried, the scent of lilies still clinging to my coat, I stood in our…

“Get me a coffee and hang up my coat, sweetheart,” the Ceo snapped at me in the lobby. “This meeting is for executives only.” I nodded… And walked away in silence. 10 minutes later, I stepped onto the stage and said calmly, welcome to my company.

The coat hit my arms like a slap delivered in silk. Cashmere. Midnight navy. Heavy enough to feel expensive, careless…

End of content

No more pages to load