The red banner didn’t flash. It smirked.

ACCESS DENIED.

A tiny strip of color on my monitor, the kind most people ignore—until it’s their name on the lock and their fingerprints on the door. I was halfway through my morning coffee, the bitter kind that tastes like discipline, when Slack chimed and the notification landed like a slap.

Trent Mallerie had stripped my admin access to the compliance sync server.

No heads-up. No “quick chat.” No HR invite with polite corporate padding. Just a silent click somewhere in a glass-walled conference room, and suddenly the system I’d built to keep a $9.2 billion asset firm clean in the eyes of regulators was treating me like malware.

I didn’t spill my coffee. I didn’t storm down the hallway like a movie character with righteous rage and perfect hair. I just blinked once, set the mug down, and walked to the file cabinet where I kept the hard copy vendor agreement.

Signed. Stamped. Ink pressed into paper so deep it might as well have been carved into stone.

Because you don’t build systems that protect billions in regulated capital without keeping your own receipts.

And Trent—poor, shiny Trent—had just tried to fire a vendor with a Slack message.

He just didn’t know he was looking at the vendor.

Outside my window, downtown Chicago was waking up in that distinctly American rhythm—sirens fading into traffic, delivery trucks backing into loading bays, a cold wind cutting down the street like it had somewhere important to be. Somewhere in D.C., people in suits were already sipping coffee and reviewing dashboards that depended on compliance logs like oxygen.

And Trent, in the middle of it all, had chosen this morning to pick a fight with the infrastructure.

What he thought he was doing: cutting “overhead.”

What he actually did: pulling the spine out of the company and acting surprised when it couldn’t stand.

He’d only been at Leborn Capital for two weeks when he started talking like he owned the building. Not the lease, not the mortgage—the building. He had that kind of confidence that comes from a fresh title and a fresh haircut and never having paid for a mistake with your own blood.

He strutted into the first “strategic savings” meeting like he was headlining a conference, not presenting to exhausted executives who’d lived through more regulatory changes than he’d had job titles.

He stood at the front of the war room, clicker in hand, and talked about “owning the stack” like it was a moral virtue. He waved a cost optimization chart like it was scripture, circling red bubbles on a slide deck that looked suspiciously like it had been assembled by someone who’d never touched production.

One bubble was labeled:

VENDOR REDUNDANCIES

Under it, a bullet point that felt personal even before I knew it would become a lawsuit waiting to happen.

DECOMMISSION THIRD-PARTY SHARED ENVIRONMENT — $38K/Q SAVINGS

That was me.

Not my name, of course. Never your name. They don’t use names when they’re planning to cut you. They use budget lines and fake smiles and phrases like “right-sizing.”

Trent grinned at the CFO and promised, “We’ll save seven figures in six months.”

I didn’t flinch. I didn’t protest. I didn’t stand up and do the whole “actually” speech.

I just noted the timestamp on the slide deck and saved a screenshot.

Because I already knew what he didn’t: that same deck was going to cost them $4.9 million.

Over the next weeks, Trent got bolder. He started revoking licenses like he was cleaning out a junk drawer. Resetting admin roles. Running audits I wasn’t copied on. He had a junior dev from finance—finance—rewriting permissions for folders tied to legally mandated audit trails.

They broke the metadata sync twice. Took one SOC2 queue offline for three days and didn’t even realize it until a compliance analyst couldn’t generate a report.

Still, I didn’t raise my voice.

I didn’t need revenge.

I had a contract.

And contracts don’t care about swagger.

The thing Trent never understood—because no one had forced him to understand it yet—was that our “shared drive” wasn’t a drive. It was a compartmentalized vendor environment. Zero trust. Federated access. Immutable logs. Encryption keys rotated under my firm’s policy.

I’d designed it that way on purpose.

Insider risk is not a theoretical concept in an asset firm. It’s a headline waiting to happen. It’s a senator holding up a printout in a hearing, asking why a “minor permissions change” turned into a breach.

So I built the environment like an airlock.

You don’t open it without permission. You don’t override it without consequences. And you don’t get the keys just because you have a title.

Which meant no one at Leborn—no matter how loudly they talked about “owning the stack”—could access the underlying services without pinging Valencet LLC.

My LLC.

My company.

My name on the vendor-of-record.

When Trent started “cleaning up phantom accounts,” he didn’t realize he was deleting the only credential relay that kept their regulatory tracebacks alive.

He thought he was disabling a drive.

What he was really doing was severing the compliance backbone of a firm that lived under the watchful gaze of U.S. regulators and auditors who do not accept “oops” as a defense.

And I waited.

Because every decision he made—every careless revoke, every smug Slack message—was just him walking the company closer to a wall.

A wall I’d already reinforced with legal concrete.

The memo went out the first Monday after New Year’s.

Subject line: Q1 STRATEGIC SAVINGS ROADMAP

It was full of vague jargon and clip-art arrows that pointed nowhere. Buried on slide six was the line that made my mouth go dry—not from fear, but from disbelief at the audacity.

DECOMMISSION THIRD-PARTY SHARED ENVIRONMENT OPS — $38K/Q SAVINGS

That’s what I was to them.

Thirty-eight thousand a quarter.

A rounding error in a firm that managed billions.

A number on a slide made by someone who didn’t know the difference between “redundant” and “required by law.”

The next day, Trent ran his little show from the corner of the war room. Click here. Script there. Cloud console in one window, ego in the other. Half the staff had no idea what he was doing—they just nodded along like obedient bobbleheads, sipping cold brew while he rambled about “regaining operational ownership.”

Someone from marketing whispered, “Is that safe?”

Trent winked like he was flirting with danger. “We’re not cutting anything we can’t rebuild.”

I nearly laughed.

Rebuild.

He couldn’t rebuild a sandwich without a tutorial.

Then came the mistake that turned his arrogance into a countdown timer.

He revoked six user groups tied to external authentication.

One of them was my vendor credential. Another was the automation relay for the compliance tracebacks they were obligated to maintain.

When I flagged it—calmly, professionally, in writing—he replied with one sentence.

We don’t need middlemen.

No signature. No emoji. Just raw arrogance pretending to be leadership.

That’s when I stopped thinking of Trent as a problem and started thinking of him as an event.

An inevitable collision between ego and reality.

Because he wasn’t cutting fat.

He was cutting bone.

My environment wasn’t some Dropbox workaround. It wasn’t a shortcut.

It was a fully compartmentalized compliance architecture that separated operations from governance—because no one at Leborn had wanted the responsibility of owning it. They wanted the benefits. The clean audit trails. The automated reports. The “we’re always ready” confidence.

They wanted it to work like magic.

So I built it like infrastructure, not a favor.

And I wrapped it in contracts so tight you could bounce a lawsuit off them.

Clause 4.3: any interference without 30-day written notice triggers default escalation.

Clause 6.2: early termination without cause triggers a flat penalty of $4.9 million due within 14 days.

Clause 8.1(c): credentialed access remains vendor property and cannot be transferred or mirrored without written permission from both parties.

It was all right there.

All spelled out.

All signed by a CFO who’d been smart enough to listen when I said, “If we do this, we do it correctly.”

Trent never read it.

Why would he?

He thought I was just internal tech support with a fancy title and a “shared drive” he could shut down like a light switch.

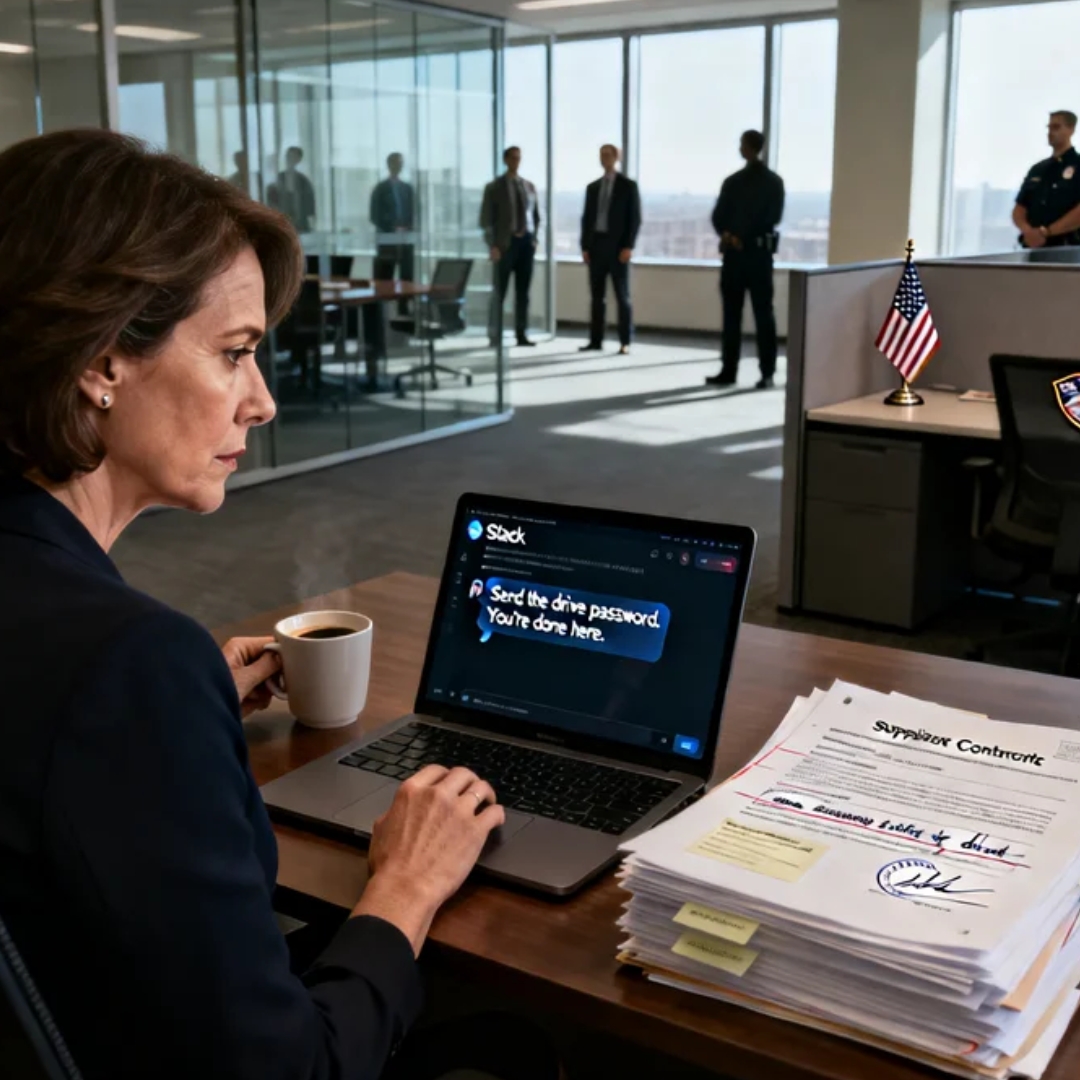

Then came the Slack message at 9:42 a.m. like a bad joke with a timestamp.

Send over the drive password. You’re done here. Desk cleared by noon.

No punctuation.

No HR.

No exit packet.

Just digital cruelty dressed up as efficiency.

I stared at it, not shocked—just briefly impressed by the stupidity. He hadn’t even tried to pretend it was legitimate.

So I typed one line back.

There is no password. That environment is vendor-managed under Valencet.

Then I logged out.

I didn’t wait for his reply.

I walked to the break room, poured the last half inch of burnt coffee from the pot Trent always complained about but never refilled, and stirred in a sugar packet that expired two years ago.

When I returned, my internal email was already disabled. A gray box where my inbox used to be.

He thought he’d erased me.

He didn’t understand something basic:

I wasn’t cut out of the system.

I was the system’s owner.

Ten minutes later, my phone rang.

Not Trent.

Not HR.

Legal.

A voice whispering like she was calling from a church pew.

“Did you just get fired?”

I let the silence stretch long enough for her to hear her own panic.

Then I said calmly, “My firm just lost a client under breach.”

On the other end, I heard her inhale like she’d realized the building was on fire and no one had pulled the alarm.

“Please tell me you didn’t give him access,” she said.

I didn’t answer.

I didn’t have to.

Silence can be a signature if you know how to use it.

She whispered, “Oh God,” and hung up.

Because Trent had just done something magnificent in its stupidity: he’d created a written, timestamped paper trail proving he demanded access to a vendor-managed compliance environment he didn’t own, immediately after terminating the vendor relationship without notice.

He didn’t just burn the bridge.

He emailed the wreckage to legal with his name stamped on every beam.

Within half an hour, his Slack message had been forwarded to the CEO.

And if you’ve ever watched a CEO learn—truly learn—that a problem is bigger than their ego, you know the look.

It’s not anger first.

It’s fear.

Because a compliance breach isn’t just an inconvenience. It’s a public event. It’s fines. It’s audits. It’s regulators asking why your “controls” failed. It’s clients yanking funds because they smell instability.

And Leborn’s entire reporting pipeline—the one that kept their numbers clean and their disclosures on schedule—ran through the environment Trent had just tried to “decommission.”

At 10:15, the first alert hit in finance. SEC artifact sync failed checksum validation.

At 10:22, the weekly retention protocol for financial statements failed.

Then the compliance calendar bot went silent, returning a message that made people’s faces drain of color:

ACCESS DENIED. CREDENTIAL MISMATCH. CONTACT VENDOR.

Contact vendor.

Three words that sound harmless until you realize you just fired the vendor.

Trent’s little “optimization team” tried to brute-force access. Reset roles. Clone permissions. Spin up shadow environments.

All of it failed.

Because every attempt triggered tamper logs that were designed to do one thing: document unauthorized interaction.

And by midday, legal didn’t need a forensic investigation. They just needed a printer.

They walked into the executive suite holding pages of logs like evidence at a trial.

And there it was, stamped into the system’s language and the contract’s language at the same time:

VENDOR KEY MISSING.

ESCALATION PATH DISABLED PER SECTION 6.2.

BREACH PROTECTION ACTIVE.

Suddenly, the question in the CEO’s office wasn’t “Can we fix it?”

It was “Who owns Valencet?”

Not what it is.

Not who runs it.

Who owns it.

Because ownership is the thing that matters when the lights go out.

And the answer was simple.

“She does.”

The CFO call scheduled for noon got canceled because the deck links returned 403 FORBIDDEN. Not missing. Forbidden. The files were still there. The system was still alive.

It just didn’t recognize them anymore.

That’s the cruel part of good architecture: it doesn’t fail dramatically. It fails correctly. It refuses to cooperate when you violate the terms that keep it secure.

By 3:36 p.m., the general counsel emailed me.

Subject: Recontractual clarification

Polite phrasing. Soft language. Corporate manners stretched over desperation.

“Would you be open to consulting on a temporary reconfiguration…”

Consulting.

Temporary.

They still couldn’t bring themselves to say “we need you.”

My lawyer replied instead.

He attached the contract.

Highlighted Section 6.2.

Attached a timeline of events: the Slack termination, the immediate lockout, the unauthorized access attempts, the failed reporting.

And at the bottom, an invoice.

$4.9 million.

No fluff.

No drama.

Just the number Trent had triggered like a landmine he didn’t know existed.

The next morning, Trent’s Slack went dark.

No announcement. No goodbye. No heroic speech about innovation.

Just gone.

Corporate disappearance. The kind reserved for people whose mistakes are too expensive to explain.

Later that day, I got a message from the CEO.

Not legal. Not HR.

Him.

He acknowledged protocol hadn’t been followed. Said termination was mishandled. Said he valued what I built.

I didn’t reply.

My counsel did.

Two lines. Receipt confirmed. Correspondence logged.

Because an apology doesn’t restore systems.

It doesn’t reverse breach.

It doesn’t untrigger the clauses I’d spent years embedding into their infrastructure like steel rebar.

The board met behind closed doors the following Thursday.

No observers. No company-wide memo until after the vote.

By then, they’d managed to keep the lights flickering with cached credentials and stopgap manual overrides, but it wasn’t sustainable. They were one audit cycle away from having to explain to an outside reviewer why their compliance pipeline suddenly became “unstable” right after a VP decided to cut “middlemen.”

So they voted.

Valencet was reinstated under an emergency continuity contract.

Not a favor.

Not a handshake deal.

A governance-level agreement with dual-approval termination requirements.

Meaning: no more rogue VPs. No more Slack firings. No more macho “we’ll rebuild it” fantasies.

If they ever wanted to remove Valencet again, it would require board and legal signatures.

It would require accountability.

It would require adults in the room.

At 4:13 p.m., the compliance environment came back online.

No corruption. No missing logs. No sabotage.

Because I never touched their data.

I never had to.

I just stopped holding the door open after they told me to leave.

And after the reinstatement, I pushed one tiny update.

A footer. Invisible to most people. But not to anyone who knew how to read a system the way you read a contract.

ACCESS PROVIDED UNDER CONTINUITY CLAUSE 8.2. TERMINATION REQUIRES DUAL APPROVAL.

No revenge.

Just a permanent reminder embedded in the daily workflow.

A quiet asterisk that would live inside their infrastructure long after Trent’s name had been scrubbed from org charts and memories.

Now, every Monday at 3:00 a.m., the compliance stack performs the same silent handshake.

Key rotation. Integrity verification. Audit log sealing.

And then, like clockwork, it sends a ping to Valencet.

Not because it misses me.

Because that’s what ownership looks like when you build things correctly.

I still don’t show up on their org chart. My badge was never reactivated. No one offered me a seat at the table.

They don’t need to.

The table checks with me before it dares to stand.

And if you think that sounds harsh, consider this: I didn’t change who I was.

I didn’t become ruthless.

I became visible—because the moment they tried to erase me, the entire machine revealed exactly what I’d been holding up.

Some people spend careers begging for respect.

I never begged.

I built something that demanded it.

And when Trent decided I was “overhead,” the contract proved, in perfect U.S. legal language, exactly how expensive it is to confuse the person who keeps you compliant with the thing you can cut.

Every week, the system logs one line.

HANDSHAKE COMPLETE.

No applause. No drama.

Just proof.

Still here.

Still mine.

The first thing people misunderstand about compliance failures is that they don’t explode.

They spread.

Quietly. Politely. Like a stain that starts at the cuff of a white shirt and ends up on your face right when the cameras turn on.

By Friday, Leborn Capital was pretending everything was “stabilized.” The internal memo said “temporary disruption.” The CEO’s assistant said “minor permissions issue.” Someone in Investor Relations called it “a routine vendor transition.”

In America, there’s a special kind of lie executives love: the kind that sounds like it belongs in a quarterly letter.

But the systems didn’t care about their phrasing.

The systems only cared about one thing: the environment had been interfered with, the keys had rotated, and the chain of custody wasn’t intact anymore.

And in a regulated world, “not intact” is a phrase that doesn’t age well.

On Monday at 8:07 a.m., the first external tremor hit—small enough that most people didn’t feel it, but sharp enough that the right people did. A senior analyst in risk couldn’t pull a verified audit bundle for a client request. It was supposed to take thirty seconds. Instead, the portal returned a clean, clinical message:

Verification unavailable. Please retry later.

That analyst did what analysts always do when something feels off: she escalated.

She didn’t send it to IT.

She sent it to Legal, Compliance, and the office of the CFO.

Because she’d been trained the American way: if it touches disclosures, you don’t treat it like tech. You treat it like liability.

At 8:19 a.m., the CFO’s calendar assistant—human, not automated—walked into the war room with a printed email in her hand like it was a medical result.

“We have a client diligence call at ten,” she said, and her voice had that tight edge people get when they’re trying not to sound afraid. “They want updated SOC2 evidence and the last twelve months of audit-ready trails. They’ve asked for it in writing.”

In writing.

That’s when the room went still.

Because the moment a request like that goes in writing, it stops being “internal inconvenience.” It becomes documentation. It becomes discoverable. It becomes something you’ll someday wish you’d handled with less ego and more caution.

Someone—one of Trent’s consultants, the kind with a tidy haircut and too much confidence—cleared his throat and said, “We can reproduce the logs.”

A compliance director snapped back without even looking at him. “You can’t reproduce chain of custody. You can’t recreate immutability. That’s the point.”

And there it was.

The difference between people who build decks and people who live under regulatory reality.

Chain of custody isn’t a vibe. It’s a requirement.

It’s a courtroom word.

It’s a headline word.

By 9:03 a.m., they were on their third attempt to “reconstruct” a verified audit bundle. The output looked fine to an untrained eye—timestamps, file names, hashed signatures.

But the verification stamp wasn’t there.

The stamp that proved the bundle hadn’t been edited, touched, duplicated, or quietly “cleaned up” by someone trying to make a deadline.

And without that stamp, it wasn’t proof.

It was a story.

At 9:11 a.m., someone finally said my name out loud.

Not in the dramatic way people imagine, like a villain being summoned. More like a person admitting they forgot to lock the door.

“Can we… reach her?” the CFO asked, eyes flicking toward Legal.

Legal didn’t answer him at first. They didn’t want to say what they’d already realized, because saying it out loud made it real.

Then the general counsel spoke, voice flat.

“We already did.”

Silence.

Then, softer: “Through counsel.”

And it landed like a weight.

Because nobody likes lawyers—until the moment the building starts shaking.

Leborn had spent years treating my vendor environment like background music. It was always there. Always running. Always humming.

They didn’t understand that background music is still coming from speakers.

Speakers you have to pay for.

Speakers you don’t own.

At 9:34 a.m., an emergency call went out to the board’s compliance committee. It wasn’t a full board meeting yet—that was the thing they tried to avoid until the last possible second, because nothing spooks markets like a sudden “special session.”

But committee calls are where the tone changes. Where people stop pretending.

A board member dialed in from a car—New York plates, judging from the background noise. Another was in an airport lounge, the kind with marble counters and quiet panic. The CEO was in his office, the blinds half closed, looking like he’d aged five years since the Slack screenshot hit his desk.

Someone asked the question nobody wanted to ask because it made everyone look foolish:

“How did a VP have the power to trigger a breach?”

The general counsel didn’t flinch.

“He didn’t have the power,” she said. “He took the action.”

There’s a difference.

America is built on that difference.

A title doesn’t protect you from consequences. It just gives you a bigger platform to fall from.

At 10:02 a.m., the diligence call started. The client was polite, as Americans in finance often are—polite doesn’t mean calm. Polite means they’re collecting evidence.

They asked for the SOC2 bundle. They asked for verification stamps. They asked for continuity controls. They asked, in that slow, measured tone, whether Leborn had experienced any “material disruptions” to audit and compliance systems in the last thirty days.

The CEO glanced at Legal.

Legal shook her head—once.

No.

Not a lie. Not technically.

Just a carefully constructed omission.

Because “material disruption” is a phrase that opens doors you don’t want opened.

The CEO answered with a sentence built of fog.

“Nothing material to operations.”

And then the client said something that sliced through the room like cold air:

“Understood. Please send that statement in writing.”

That’s when the CFO’s face changed.

Because in finance, the phrase “in writing” is the moment you feel your heart beat in your throat.

It’s the moment you realize your words will outlive you.

It’s the moment you realize you don’t control the narrative anymore.

You only control the evidence.

And the evidence was sitting behind a locked compliance environment that didn’t recognize them.

At 11:20 a.m., the CEO’s assistant walked out of his office with his personal iPad tucked against her chest, like she was protecting it.

She crossed the war room and placed it on the table in front of the general counsel.

On the screen was a draft email the CEO had started, then stopped, then started again.

I know because you can see that in the way the cursor hovers, and the way the lines are rewritten.

It wasn’t addressed to HR.

It wasn’t addressed to Trent.

It was addressed to my lawyer.

And it began with five words that, in corporate America, mean one thing:

We regret how this occurred.

Regret.

Not apologize.

Regret is what you write when you’re admitting fault without admitting liability.

My attorney answered that afternoon with two pages and one sentence that mattered most.

Payment confirms reinstatement.

Everything else was context.

Everything else was structure.

Everything else was the quiet discipline of making sure this could never happen again—not because feelings were hurt, but because governance failed.

Meanwhile, Trent had gone silent.

Not “busy.”

Not “in meetings.”

Silent like a light switched off.

His Slack was gone. His calendar invites stopped coming. His name disappeared from distribution lists like it had never existed.

In the hallways, people stopped saying “Trent.” They said, “Operations leadership” or “the transition team,” the way people talk around a mess they don’t want splashing on their shoes.

But the consultants he brought in—those were still there, still pacing, still typing, still insisting they could “rebuild” what they didn’t understand.

At 2:07 p.m., one of them tried to spin up a parallel environment to mirror mine.

It was a clean attempt. Technically competent.

But it revealed the one thing they couldn’t fake:

They didn’t have the root of trust.

They could copy a folder.

They couldn’t copy legitimacy.

The clone environment pinged the verification layer and got rejected instantly.

Not with a dramatic alert. With a boring, brutal line in a log:

Unverified environment. Chain-of-custody mismatch.

That’s the thing people never consider when they underestimate quiet work.

Quiet work is still engineered.

Quiet work is still guarded.

Quiet work is still built to outlast whoever happens to be holding a title this quarter.

By Tuesday, the board had stopped debating whether they should reinstate Valencet.

They were debating how to present it without looking incompetent.

Because optics matter in American finance the way oxygen matters in a hospital.

You can’t see it, but if it goes missing, everyone panics.

Someone suggested, “We call it a continuity partnership.”

Someone else suggested, “We frame it as a security upgrade.”

The general counsel didn’t care what they called it. She cared about what it did.

She wanted dual approval termination.

She wanted the vendor index embedded into onboarding.

She wanted a hard rule that no VP, no matter how shiny, could “optimize” a regulated pipeline without Legal sign-off.

The CEO signed it all.

Then he signed the payment.

And at 4:13 p.m., the environment came back.

Not because they begged.

Not because I needed to “win.”

Because the contract required conditions, and those conditions were finally met.

It wasn’t a triumph. It was a restoration.

No data lost.

No mysterious gaps.

No damage control stunt.

Just systems snapping back into place like they’d been waiting for adults to return to the room.

Then came the quietest part—my favorite part.

The updated footer.

Small. Non-dramatic. Impossible to ignore if you knew where to look.

Access provided under continuity clause 8.2. Termination requires dual approval.

No revenge language.

No gloating.

Just an asterisk stitched into their daily workflow like a scar you don’t talk about, but you never forget.

Because in corporate America, the biggest flex isn’t shouting.

It’s being the thing that still runs when everyone else is replaced.

Now every Monday at 3:00 a.m., a scheduled handshake fires in the compliance stack. It verifies integrity logs, rotates keys, checks off-site backups, and pings Valencet.

Nobody watches it.

Nobody celebrates it.

They don’t have to.

It’s proof.

And proof is the only language the system speaks.

Weeks later, I heard Trent had taken a “personal leave.”

That’s what they call it when they don’t want a headline.

The consultants were quietly phased out.

The CEO started showing up to meetings with Legal seated beside him like a shadow.

And every new executive onboarding packet includes a vendor index, with Valencet highlighted at the top.

Not because they suddenly loved me.

Because they finally understood something Trent never did:

You can remove access.

You can’t remove ownership.

And when you try to pretend you can, the silence that follows isn’t a drama.

It’s a lesson.

A quiet one.

The kind that costs $4.9 million.

The story didn’t end when the systems came back online.

That’s the part people always get wrong.

In America, disasters don’t end with recovery. They end with reputations adjusting. With names quietly moving up or disappearing. With certain doors never opening again, no matter how many times you knock.

By the following Wednesday, Leborn Capital looked normal from the outside.

The lobby still smelled like citrus cleaner and expensive coffee. The screens still looped the same mission statements. Analysts still hurried past with laptops tucked under their arms like shields.

But underneath that polished surface, the hierarchy had shifted.

And everyone could feel it.

Trent’s office was dark.

Not empty—dark. His nameplate was still on the door for two full days after his access was revoked. No one removed it. No one touched it. It was like a warning label people pretended not to see.

By Thursday morning, it was gone.

So was his calendar.

So was his authority.

No farewell email. No “we thank him for his contributions.” No carefully worded LinkedIn post with comments turned off.

Just absence.

In American corporate culture, that’s worse than public failure. Public failure at least gives you a narrative. Silence means the company has decided you are no longer worth explaining.

Inside the building, people recalibrated fast.

The junior dev Trent had leaned on avoided eye contact with anyone from compliance. The consultants stopped using the phrase “own the stack” and quietly asked Legal to review everything. Middle managers who’d nodded along during Trent’s presentations suddenly remembered they had concerns.

That’s how survival works in places like Leborn.

Everyone has principles—right up until the org chart shifts.

The Slack screenshot made its rounds anyway.

Someone always leaks.

It showed Trent’s message to me in full, timestamp and all. No punctuation. No HR. No legal. Just authority assumed and exercised without permission.

By Friday, people were quoting it in private DMs like folklore.

“Send over the drive password. You’re done here.”

Fourteen words that cost the firm $4.9 million and a quarter’s worth of credibility.

The CEO never acknowledged the leak publicly. He didn’t need to. He handled it the American way—by rearranging proximity to power.

At the next all-hands, Legal sat front row.

Compliance spoke before Operations.

And the phrase “vendor-managed environments” appeared in the slide deck no fewer than nine times.

Language is policy before policy is written.

People learn quickly what words not to mock.

I wasn’t invited to that meeting.

I wasn’t supposed to be.

Vendors don’t sit in all-hands.

But my work did.

Every chart that loaded correctly. Every audit artifact that verified cleanly. Every automated report that arrived on time without drama.

Quiet proof.

That’s the kind that lasts.

A week later, the CEO asked for a call.

Not through Legal this time. Direct.

I took it from my kitchen, barefoot, sunlight cutting across the counter. He sounded different—less guarded, more tired.

“I want to be clear,” he said. “We’re not asking for favors. We’re asking for continuity.”

I let him talk.

He explained that the board had reviewed the incident as a governance failure. That new controls were being drafted. That no single executive would ever again have unilateral authority over regulated infrastructure.

He said my name carefully.

“We underestimated you,” he admitted. “That won’t happen again.”

That was as close to an apology as men like him get.

“I’m not interested in being underestimated or celebrated,” I replied. “I’m interested in systems that work and contracts that are respected.”

He agreed quickly.

Too quickly.

People only agree that fast when they’ve learned the cost of not doing so.

The revised agreement arrived that afternoon.

Longer. Tighter. Cleaner.

Valencet was no longer just a vendor. It was listed as a continuity partner, embedded into risk disclosures, referenced in governance documentation.

Not because they suddenly valued me.

Because the regulators would.

That’s the difference.

By the end of the month, the story had settled into its final form.

Externally, Leborn framed the incident as a “strategic compliance realignment.” Analysts nodded. The stock stabilized. Clients stopped asking uncomfortable questions.

Internally, something more permanent had changed.

People stopped assuming.

Stopped “optimizing” what they didn’t understand.

Stopped confusing access with ownership.

Every major system change now ran through Legal, Compliance, and—quietly—my environment.

No one announced it.

No one needed to.

The work spoke for itself.

Trent’s name never came up again.

Not in meetings.

Not in retrospectives.

Not even in jokes.

He became a lesson without a caption.

That’s the final stage of corporate consequence—the erasure phase.

I still don’t have a badge.

I don’t have a title on their website.

I don’t attend strategy off-sites or drink the catered coffee in glass conference rooms.

But every Monday at 3:00 a.m., long before the building wakes, the system checks in with me.

Handshake complete.

Integrity verified.

Still operational.

Still compliant.

Still mine.

People think power looks loud.

It doesn’t.

Real power looks like a system that keeps running after you’ve been deleted from the org chart.

It looks like a contract that speaks when you don’t have to.

It looks like silence that costs millions.

And the funny thing is, if Trent had just asked—if he’d read one clause, sent one email, shown one ounce of restraint—none of this would have happened.

But America doesn’t reward humility in resumes.

It rewards it in outcomes.

And now, every executive at Leborn knows something they didn’t before.

There are people you see.

And there are people everything depends on.

They finally learned the difference.

Not because I shouted.

Not because I fought.

But because when they tried to erase me, the system remembered exactly who I was.

News

“Daddy, there’s a red light behind my dollhouse,” my 6-year-old whispered at bedtime. When I checked, I found a hidden camera. My wife said she didn’t put it there. The truth would tear our family apart…

The red light appeared only after midnight. That was the part that still haunted me—the way it waited for the…

My mom invited everyone to her 60th birthday, except me and my 8-year-old. She wrote: “All my children brought this family respect-except Erica. She chose to be a lowly single mom. I no longer see her as my daughter.” I didn’t cry. Next time she saw me, she went pale because…

The night my mother erased me, the air in our apartment smelled like peanut butter, pencil shavings, and burnt toast…

My brother got engaged to a billionaire Ceo, and my parents decided that I was “too unstable” for the engagement. “Your brother’s in-laws are elite-you’ll humiliate us. Don’t ruin this.” dad said. Until the Ceo recognized me in the closing room and screamed that I was the forensic auditor she hired

The first thing my father did wasn’t yell.He didn’t ask how I was.He handed me a court order like a…

At my 30th birthday dinner, my mom announced: “time for the truth-you were never really part of this family. We adopted you as a tax benefit.” my sister laughed. My dad said nothing. I stood up, pulled out an envelope, said: “funny. I have some truth too.” what I revealed next made mom leave her own home.

The first thing I noticed was the wine stain. Not the people. Not the mood. Not even the sharp little…

“You get $5, Danny” my brother smirked, ready to inherit dad’s $80m fishing empire. I sat quietly as the partner pulled out a second document… My brother’s face went white

The first lie tasted like cheap coffee and salt air. “Five dollars,” my brother said, like he was reading the…

When I found my sister at a soup kitchen with her 7-year-old son, I asked “where’s the house you bought?” she said her husband and his brother sold it, stole her pension, and threatened to take her son! I just told her, “don’t worry. I’ll handle this…”

The duct tape on her sneaker caught the sunlight like a confession. One strip—gray, fraying at the edges—wrapped around the…

End of content

No more pages to load