By the time the Texas sun hit its stride, Main Street looked like it was on fire.

Heat shimmered up from the asphalt in visible waves. The air over downtown Hartfield had that thick, oily weight that makes every breath feel like work. A stainless-steel hot dog cart gleamed on the corner of Main and Fifth, metal so hot you could fry an egg on it.

Sergeant Dale Crawford made the whole scene worse just by standing in it.

His patrol cruiser squatted half on the curb in a no-parking zone like it owned the sidewalk. The engine idled, AC humming, while Crawford leaned in close to the man behind the cart—close enough that his badge caught the light like a threat instead of a shield.

“Three hundred cash every Friday,” Crawford said, voice low and lazy, as if he were talking about the weather. “You got that, boy? Or is counting a little too advanced for you?”

The vendor didn’t flinch.

He was Black, mid-thirties, skin sheened with sweat from the heat and the steam rising off the warmer. An apron covered most of his T-shirt. His hands were big, the kind that looked like they’d done a lot of real work. They rested on the cart where Crawford could see them.

“I understand, Sergeant,” he said quietly. “I just started here two months ago. I—”

“Did I ask for your autobiography?” Crawford snapped, jabbing a finger toward his face. “Shut your mouth and listen. This permit—” he slapped the laminated paper posted on the side of the cart hard enough to make it rattle—“is toilet paper if I say so. One phone call and your whole world gets pulled apart.”

He leaned in closer still, breath smelling of burnt coffee and cheap cologne.

“And for someone like you?” he added, letting his eyes drag slowly over the vendor’s dark skin. “There’s always something they can find. Background checks. Immigration checks. Paperwork mysteriously going missing. They dig until they hit something. They always do.”

The vendor’s jaw tightened. His hands did not.

He opened his cash box, counted out fifteen twenties with careful, steady fingers, and held the folded stack out.

Crawford snatched the money without counting it. It disappeared into his pocket like it had been his all along. He gave the vendor’s cheek a sharp, dismissive pat, just this side of a slap.

“Good,” he said. “You can learn. Maybe you’re trainable after all.”

He turned his back without another word and sauntered toward his cruiser, boots landing heavy on the concrete like each step was a reminder of who owned this street. He got in, shut the door, and drove away, never once looking back at the man he’d just shaken down.

Under the apron, near the second button, an almost invisible red light kept blinking.

Still recording.

Sergeant Dale Crawford of the Hartfield, Texas Police Department had just extorted an undercover deputy U.S. Marshal.

He had no idea.

Stay with this one.

Seventy-two hours earlier, Tuesday morning, 6:15 a.m.

Hartfield was still half-asleep when Scott Davidson pushed his hot dog cart off the trailer and onto the cracked sidewalk at Main and Fifth. The sun hadn’t fully cleared the low buildings yet, but the promise of Texas heat already hung in the air, thick and unforgiving. Somewhere nearby, a freight train groaned awake.

Scott’s cover file said he was thirty-eight, recently divorced, starting over after a factory job disappeared when the plant moved overseas. Army veteran. Honorably discharged. Two kids who lived with their mom in another state. Savings gone. Last shot was this cart.

Most of that was true.

What the file didn’t say was the badge he carried in a different life, the oath he’d sworn, or how much he hated the taste of street-vendor coffee after drinking it for eighteen months straight in four different cities.

He popped open the stainless-steel lid and checked the water level. Steam rolled up, fogging his face. He set the mustard, ketchup, relish, onions, napkins, and tongs exactly where he always did. Everything in its place. Always. That part was easy. They’d trained him for that.

Four other vendors shared this block of Main Street, each staked out on a patch of concrete they’d paid for in sweat and time.

About thirty feet down, Elena Vargas was unfolding the awning on her taco cart. Sixty-two, Mexican American, silver hair braided and pinned at the back of her head. Eleven years on this corner. She moved with the slow, practiced efficiency of someone who had done this so many times her body remembered without asking.

She walked toward Scott carrying two Styrofoam cups of coffee, steam curling up into the morning haze.

“You’re the new one,” she said, pressing a cup into his hand without asking if he wanted it. Her accent softened the edges of the words.

“Yes, ma’am,” Scott said. “Two months.”

Elena’s gaze flicked briefly toward the street. A patrol car rolled past at an unhurried crawl, windows down, an officer’s elbow resting on the frame. The car moved like a predator that wasn’t hungry yet but liked knowing you were there.

“Be careful around here,” Elena said.

Scott took a sip of the coffee. It tasted like burnt dirt and kindness.

“Careful of what?” he asked.

Elena watched the patrol car until it turned off Main and disappeared.

“Just… careful,” she said. She went back to her cart without explaining.

Her hands shook a little as she set out her salsa containers.

Across the street, Tyler Williams arranged fruit into neat rows on his wooden stand. He was twenty-eight, Black, lean, with the kind of wary stillness that said he’d learned early not to draw attention. Every time a police car passed, his shoulders tightened. His eyes dropped automatically. He never made eye contact with a badge if he could help it.

Farther down, closest to the intersection, was Henry Dawson’s pretzel cart.

Henry was seventy-one, Black, with faded Navy tattoos on his forearms from the time America sent him to Korea and promised the world would be different when he got home. Thirty-four years on this corner. His hands trembled when he counted change now—not just from age, Scott suspected. Henry caught Scott’s eye and gave a little wave. A silent nod passed between them. Two Black men in aprons on a Texas sidewalk, acknowledging each other’s existence in a city that liked to pretend they were scenery.

The morning started slow. Office workers drifted in. Tourists wandered through, sleeves already soaked with sweat by nine a.m., clutching maps and phones. A city maintenance crew jack-hammered a block away, sending vibrations through the soles of everyone’s shoes.

By noon, Scott knew a few regulars by their orders.

Sausage with everything, no mustard for the nervous man who checked his phone after every bite.

Plain dog, extra napkins for the woman with the perfectly pressed suit who never made small talk.

Tourists rarely tipped. Locals sometimes did. Kids always stared at the steam.

Elena stopped by around lunchtime and leaned against his cart, easing her weight off her feet.

“My heart isn’t what it used to be,” she said, pressing her hand absently to her chest. “Doctor says ‘retire.’” She snorted softly. “Who retires from a taco cart? You just stop one day.”

“You’ll outlive all of us,” Scott said.

She laughed, but something tired and heavy lived behind her eyes.

At 2:15 p.m., the day shifted.

An unmarked Ford Crown Victoria eased up to the curb and nosed into a no-parking zone like it belonged there. The engine idled for a moment, then cut off.

Elena saw it first.

Her face changed so fast Scott almost missed it. Warmth dropped away. Her jaw tightened. She turned her back, hands suddenly very busy reorganizing things that didn’t need organizing.

Tyler stopped arranging fruit and bent to fuss with his shoelaces, the same pair he’d tied perfectly that morning.

Henry looked up, saw the car, and went still. His jaw locked. His hands began to tremble worse than usual. He stared fixedly at some point in the middle distance, like a man bracing for a blow he knew he couldn’t dodge.

The driver’s door opened with a heavy click.

A man got out.

White. Mid-forties. Texas summer tan over a face that looked like it had been carved out of habit and resentment. His uniform was ironed sharp, creases like blades. His badge caught the sunlight in a perfect gleam. His hand fell naturally near his citation book on his belt, as if it were optional whether he wrote tickets with it or used it to ruin someone’s month.

He didn’t hurry.

He walked like he owned every inch of Main Street.

Sergeant Dale Crawford of the Hartfield Police Department crossed the street and stopped right in front of Scott’s cart.

Too close. Inside the bubble reserved for customers and friends. Inside the space where strangers had no right to be.

“You’re new,” he said. Not a question. A diagnosis.

Scott kept his hands where Crawford could see them. That was habit, too.

“Started about two months ago, Sergeant,” he said, pitching his voice to the level of cautious respect he’d heard a hundred times from people who knew they were on the losing side of a power imbalance.

Crawford’s gaze moved slowly over the permits taped to the side of the cart. City business license. County health inspection. Tax registration. Hartfield, Texas had a form for everything.

The sergeant studied each one like he was trying to find typos with his eyes alone.

“Nice little setup,” he said finally. His tone turned the words into something just shy of an insult. “You learn how things work around here yet?”

“I make hot dogs,” Scott said. “People buy them. That’s how it works.”

Crawford smiled. It was a cold expression that didn’t move his eyes.

“That’s part of it,” he said. “Here’s the rest. There’s a licensing fee on this block. Three hundred a week. Cash. You pay, everything runs smooth.”

Scott didn’t react outwardly. “Three hundred,” he repeated. “And what does that cover?”

Crawford tilted his head, the way a cat might consider how much effort to spend on a mouse.

“Covers health inspectors who don’t suddenly find things wrong,” he said. “Covers permits that don’t go missing at City Hall. Cops who don’t notice your cart maybe sticking out too far into the sidewalk.”

He took another step closer. Scott could smell the sweat beneath the cologne now.

“And for people like you,” he added, dropping his voice, “it covers questions that don’t get asked. Checks that don’t get run. Deep looks into backgrounds that don’t happen.”

“I was born in El Paso,” Scott said evenly. “Fourth-generation American.”

“Sure you were,” Crawford said. “They all say that. Until a certain form gets misfiled and suddenly nobody can find proof of anything.”

The threat hung between them like a bad smell.

“Three hundred every Friday,” Crawford said. “Don’t make me come looking. If I have to come looking, the price goes up. If I have to come looking twice…”

He leaned in until his mouth was near Scott’s ear.

“People who make me come looking twice regret it,” he said softly. “Sometimes they end up in a hospital. Sometimes there are worse places.”

“You understand what I’m saying?”

Scott opened the cash box.

His hands shook. Just enough for Crawford to see it and feel satisfied. Not enough to drop any bills.

He counted out fifteen twenties, folded them, and held them out.

Crawford grabbed the money, folded it once, and slid it into his pocket like he’d earned it.

“Good,” he said. He gave Scott’s cheek a hard little pat. “Maybe you’re trainable. Like a dog.”

He turned halfway back to his car, then paused.

“One more thing,” he said. “The others? Elena. Old Henry. The kid with the fruit stand. They’ve been here a long time. They know how things work. They don’t ask questions. They keep their heads down.”

His gaze locked on Scott’s.

“You don’t make friends on this corner,” he said. “You don’t get curious. You just sell your hot dogs, pay your fee, and Main Street stays… peaceful.”

He walked back to the Crown Vic and drove off, tires bumping casually over the curb.

Scott watched until the car disappeared around the corner.

Elena kept pretending to reorganize sauces. Tyler tied and re-tied laces that were already tight. Henry stared at a spot on the pavement like it was all that kept him from falling over.

Nobody said anything. The silence was thicker than the heat.

Scott slid a hand under his apron, fingertips grazing the tiny disk clipped near his chest. About the size of a coin. Custom hardware. The red light blinked again.

Still recording.

Three hundred dollars gone to a man with a badge who didn’t bother to hide what he was doing.

But Scott had gotten something in return.

Evidence.

And Friday was coming back around.

That was Tuesday.

By Friday, Main Street felt different.

The heat was worse. Ninety-five degrees and climbing. The air rippled over the pavement, giving everything above it a wavy halo.

Scott had been awake most of the night, watching the same two videos over and over. Tuesday’s collection. Thursday’s conversation with Henry’s doctor. But when he rolled his cart into place that morning, he moved like any other vendor starting another long day.

“Morning,” Henry said, voice hoarse.

“Morning,” Scott returned.

Nobody mentioned Crawford. Nobody had to.

At 2 p.m., the lunch rush sputtered out. Office workers retreated to air-conditioned cubicles. Tourists drifted toward the riverwalk. Vendors wiped down surfaces and checked stock. The hum of the street dropped a notch.

At 2:10 p.m., a gray haze shimmered over Main Street.

At 2:15, Crawford’s unmarked Crown Vic turned onto the block.

He wasn’t alone.

Two marked patrol units slid in behind him, light bars dark but presence unmistakable. The cars parked in a sloppy row across three spaces, forming a kind of casual barricade. Two officers got out—both white, both young, both walking with the taut, eager energy of men who enjoyed this part of the job a little too much.

Officer Dennis Briggs was tall and thick through the shoulders, face permanently arranged in a smirk. Officer Wayne Holt was thinner, eyes sharp, jaw set in a permanent clench like a man grinding his teeth through dreams.

They didn’t come to Scott’s cart.

They went to Henry’s.

The old man watched them approach from thirty feet away. His hands stopped moving. The color drained from his face. He looked very suddenly, painfully old.

Henry stood with his back to the cart, white apron already stained from the day’s work. His fingers twitched against the metal edge.

“Henry,” Crawford called, voice pitched just loud enough to carry. “We need to talk about your account.”

People on the sidewalk slowed. A few tourists glanced over, then pretended they hadn’t. A delivery driver double-parked a block away pulled out his phone, thought better of it, and put it away.

Henry swallowed.

“I have most of it, Sergeant,” he said, the words rasping out of a throat gone dry. “My wife’s medication was more this month. I’ll have the rest Monday. Thirty-four years I been here. Never missed before.”

“You’re short,” Crawford said. “Two hundred.”

“That’s all,” Henry said. “Just two hundred. Please. You know I—”

Crawford shoved him.

It wasn’t a hard push by any reasonable standard. Just enough to knock an unsteady old man off balance.

Henry stumbled. His hip caught the edge of his cart. The entire structure rocked. Pretzels slid off the display tray and tumbled across the sidewalk. One of the wheels rolled over his foot.

He fell.

The sound of his body hitting the concrete was louder than it should have been. Wet. Final.

The next sound was worse.

Crawford kicked him.

The first blow landed in Henry’s side with a hollow thud. He curled in on himself, arms wrapping instinctively around his ribs.

He was seventy-one years old, decades past the last time he’d ducked artillery fire in a war on another continent. He had survived that. Now he lay curled on Main Street, Hartfield, Texas, covering his head while a cop in a pressed uniform kicked him like he was trash left in the wrong spot.

“Stop!” Elena screamed from her cart. “Stop, he’s an old man!”

Crawford’s head snapped toward her.

“You want to be next?” he barked.

Her hand flew to her chest. She backed away, eyes wide. Whatever she’d been about to say died in her throat.

Across the street, tourists pretended not to see. No one called 911. No one filmed. No one yelled.

Briggs and Holt watched like they were at a show. Arms crossed. Smiles faint but unmistakable.

Scott’s fingers dug into the edge of his cart until they ached. Everything inside him screamed to move. To step in. To shove Crawford away from the old man on the ground. To be another version of himself who didn’t have to pretend he was just a vendor.

He didn’t move.

He was deep undercover. Eighteen months of work in three different cities had taught him exactly how fast one impulsive move could blow an operation and possibly get more people hurt.

So he watched.

And a part of him he couldn’t quite name—and would never get back—burned out.

Henry tried to push himself up on one elbow. Crawford planted his boot on Henry’s chest and pressed down.

“Stay down,” he said. “Think about what happens when people don’t pay what they owe.”

He stepped back, smoothed his uniform, and wiped his hand on his pants as if he’d touched something dirty.

“Briggs,” he said. “Call in medical. Vendor fell. Hit his head. Holt, take statements. Nobody saw a thing.”

Both officers nodded.

Twenty minutes later, an ambulance arrived. EMTs loaded Henry onto a stretcher. His white apron was spotted with red now, a smear of blood near the hem. His face was already swelling on one side.

The official report would later say that Henry Dawson slipped while moving boxes and fell against his cart.

That evening, the vendors on Main Street closed early.

Tyler came over as he packed up his fruit stand. His voice was barely louder than the rustle of the plastic bags he was tying.

“Don’t,” he said.

“Don’t what?” Scott asked.

“Whatever you’re thinking,” Tyler said. “Don’t do it.”

“I’m not thinking anything.”

“Good,” Tyler said. “Thinking gets Black men in this town hurt. Remember that.”

He walked away, shoulders hunched.

Scott pushed his cart to the trailer, hooked it up, and drove back to the small apartment he was using under a rented name.

He sat in the dark for a long time.

Then he turned on his laptop.

He created a folder labeled EVIDENCE.

He downloaded Tuesday’s video: Crawford taking money, making threats.

He downloaded today’s: Henry on the ground, blood on concrete, Crawford’s boot, the faces of Briggs and Holt.

A smart vendor would delete everything and move to another city.

Scott wasn’t a vendor.

He copied the files to an external drive. Then another. Then a secure cloud. He opened a blank document and started typing.

Names. Dates. Times. Badge numbers. Bank deposits. Patterns.

By midnight, the file was pages long.

By morning, Henry Dawson was in a hospital bed with a broken rib, a fractured cheekbone, and a concussion.

And Scott Davidson was only just getting started.

The next week turned into a rhythm of daylight performance and nighttime obsession.

Daytime, Scott was the hot dog guy.

He joked about the heat with office workers. He listened to tourists complain about flight delays and rental cars. He swapped small talk with people who thought the worst problem in their world was a wrong coffee order. He wore his apron. He kept his head down.

Nighttime, he was something else.

His kitchen counter disappeared under stacks of notes. Printouts covered the table: screenshots of city records, copies of vendor permits, lines of bank transactions. His laptop cast blue light across bare walls as he replayed videos over and over, memorizing the tilt of Crawford’s head, the exact phrasing of threats, the routine of his weekly collections.

Monday afternoon, he watched from behind his cart as Crawford stopped at Elena’s.

Three hundred.

Her hands shook so badly she dropped one of the twenties. It fluttered to the ground. She bent to grab it. Crawford didn’t move to help. When he walked away, she slumped against her cart for a second, hand pressed over her heart, eyes squeezed shut.

Scott recorded the entire exchange with the tiny camera in his apron.

Tuesday, he moved his cart a little closer to the next block and watched a woman selling empanadas dig into a worn purse. Tears ran down her face as she counted out the money, apologizing in a mix of English and Spanish for being late, for being short, for existing.

Crawford watched her pick up one bill after another from the ground, shoes planted where they were. Scott recorded.

Wednesday, Crawford and Briggs did a rapid circuit—four vendors in ninety minutes, three hundred each, plus a “penalty” from one who’d been short the previous week. Scott recorded.

Thursday, Scott drove out to Hartfield General Hospital.

Henry Dawson lay in a bed that seemed much too big for him, hospital gown gaping. His face was a map of bruises. Purple and yellow blooms spread from his left cheekbone. The skin around his right eye had swollen nearly shut. His ribs were wrapped tight, each breath a shallow struggle.

“Thirty-four years,” Henry whispered, when Scott asked how he was. “Never missed a payment. Not once. And this is what I get.”

Scott pulled out his phone.

“Henry,” he said. “Can I record you? Just… tell me what happened? In your own words?”

Henry stared at the phone for a long time.

“Why?” he asked finally. “Who’s gonna care what happens to an old Black man on a corner in Hartfield, Texas?”

“Maybe no one,” Scott said. “Maybe someone. We don’t know if we don’t try.”

After a long silence, Henry nodded.

He told his story.

He talked about the first time Crawford had come by, years ago, when the fee was “only” a hundred. How the amount had crept up. How the threats had sharpened. How he’d kept paying because he didn’t know what else to do.

Scott recorded all of it.

Outside, in the hospital parking lot, a gray sedan sat parked across from Scott’s car. Its windows were tinted. It had been there when he arrived.

It had been outside his apartment building two nights before, too.

He noted the plate number without slowing his pace.

Back on Main Street that evening, Tyler grabbed his arm near the storage unit.

“What are you doing?” Tyler demanded, voice rough. “I see you with that phone. Always recording. Always watching. You think this is a game?”

“It’s not a game,” Scott said.

“Then act like it,” Tyler said. “Crawford is not the only one you need to be afraid of. He’s got friends. Police department. City Hall. Maybe even higher. You poke at that, they don’t just slap your wrist. They make you disappear.”

Scott didn’t argue.

That night, he looked at his list.

Six vendors on video paying cash.

Three witness statements.

Hospital records for Henry.

Rough estimates of how much money Crawford had siphoned from Main Street in three years.

Enough to bring to a police department in a different world.

Not this one.

Crawford worked here. His supervisors had already “investigated” him twice and found nothing. Internal Affairs files came back clean. Complaints from vendors had vanished into paperwork voids.

The system wasn’t broken.

It was functioning exactly as designed.

Scott needed something stronger.

He needed Crawford on record, in his own words, telling the truth about what this really was.

Friday morning, the gray sedan was parked closer to his apartment.

Friday afternoon, Crawford came to collect again.

Scott paid. The man took his money. The camera in Scott’s apron captured every word.

Another file dropped into the EVIDENCE folder.

Not enough. Not yet.

But the clock ticked louder.

Because somewhere inside Hartfield PD, someone had started paying attention.

Thursday’s beating. Friday’s pattern. The way one vendor on Main Street watched everything too carefully.

By Day Eighteen, you could feel the tension on Main Street without seeing a single patrol car.

Crawford’s visits had shifted.

He wasn’t just collecting.

He was hunting.

He stood longer at each cart, eyes scanning faces as if he were reading minds instead of menus. He asked questions that had nothing to do with health permits or sidewalk ordinances.

“Anybody talked to reporters lately?” he asked the empanada vendor, leaning his elbows on her glass case. “Anyone asking about me? About the patrol schedule?”

She shook her head so quickly it looked like it might snap off.

“No, sir,” she said. “Nobody.”

“Seen any cops you don’t recognize?” Crawford pressed. “Federal types. Maybe driving rental cars. Looking around like they’re lost.”

She shook her head again. “No, sir. I just make food.”

He moved on.

At Elena’s cart, he was worse.

“You’ve been here a long time, Elena,” he said, picking up a taco shell and setting it back down as if the mere act of touching it claimed it. “Eleven years. You must see everything that happens on this corner.”

“I see my grill,” she said, eyes fixed on her hands. “That’s all.”

“Don’t insult me,” he said softly. “Someone’s been asking questions. Taking pictures. Visiting that old man in the hospital. You hear anything about that?”

Elena’s hands shook.

“No, Sergeant,” she whispered. “I don’t know anything.”

Crawford leaned in closer. The late afternoon sun threw his shadow over her entire cart.

“If I find out you’re lying,” he said, “I won’t just shut your cart down. I’ll make sure your family wonders what happened to you. Your grandchildren will grow up saying, ‘We used to have an abuela who made tacos on Main Street. One day she just… never came home.’”

Elena’s hand flew to her chest again.

“My heart,” she gasped. “Please. I—I have a condition.”

“Then you better hope it can handle what comes next,” Crawford said.

He walked away.

That night, someone trashed Tyler’s fruit stand.

Scott came down Main Street early the next morning and stopped dead.

Wood splintered. Wheels slashed. Crates overturned and stomped. Fruit smashed into the concrete and left to rot in the heat. Someone had spray-painted one word down the side of the stand, letters jagged and dripping red.

SNITCH.

Tyler stood in front of the wreckage, face blank, hands hanging uselessly at his sides.

“I didn’t say anything,” he whispered when Scott came over to help pick up the pieces. “I swear. I didn’t talk to anybody. Why would they do this to me?”

“It’s not about what you did,” Scott said, tossing another ruined apple into a trash bag. “It’s about what Crawford’s afraid of. He doesn’t know who’s watching, so he hits everyone.”

“Is it working?” Tyler asked.

Scott didn’t answer.

Officer Holt came to take a report. He wrote down a few lines, didn’t ask many questions, and left.

No suspects. No witnesses. No follow-up.

Just another vendor on Main Street whose life was quietly wrecked.

That afternoon, Crawford parked his cruiser at the end of the block and just stood there for an hour, watching.

If his eyes landed on Scott more often than anyone else’s, it might have been coincidence.

Scott didn’t believe in coincidence anymore.

That night, Scott updated his backups. Three separate secure services. One encrypted drive hidden in a wall. Another cached off-site.

He composed an email to an address that didn’t look like anything—a string of numbers and letters that meant nothing to anyone outside the public corruption task force.

Subject: INSURANCE.

Body: If something happens to me, release everything. To DOJ and press simultaneously.

He hit send.

The gray sedan parked right in front of his building that night.

No attempt to hide.

Friday came, bright and merciless.

Just after two, Crawford parked in his usual illegal spot and got out, phone pressed to his ear. He paced for a minute, talking quietly, glancing toward Scott’s cart twice.

He hung up and walked over.

He didn’t ask for money.

“You’ve been busy,” he said.

Scott kept his expression neutral. “I don’t know what you mean, Sergeant.”

“Sure you do.” Crawford leaned against the cart like it was his. “Someone’s been visiting hospitals. Talking to Henry. Taking videos. Someone’s been asking around about me.”

He held Scott’s gaze.

“That someone,” he said, “is about to wish he’d just kept flipping hot dogs and minding his business.”

He pushed off the cart and straightened up, satisfaction in the set of his shoulders.

“Have a nice weekend,” he said.

He left without collecting.

That was worse.

Much worse.

If you’ve ever wondered what happens when a Black man in Texas tries to push back against a corrupt cop with friends in all the right places, the answer is this:

The system pushes back.

Hard.

Friday night, 11:00 p.m., Scott left his apartment through the back entrance. Hoodie up. Hat low. Moving fast.

He was going to a meeting that had taken two weeks to arrange.

Three days earlier, a message had come in through a secure channel, bounced through enough encrypted servers to make it nearly impossible to trace. The sender claimed to have information on Crawford’s boss. Claimed the rot went higher than one sergeant. Claimed to have names.

The meeting point was an industrial parking lot on the edge of town, between two abandoned warehouses, the kind of place where nobody asked questions about who met there and why.

Scott arrived at 11:30.

The lot was mostly dark. One streetlight flickered overhead, buzzing like an insect caught between life and death. No cars. No movement. Wind whispered through a chain-link fence.

He checked his watch.

He checked the shadows.

Headlights appeared at the far end of the lot.

A white van rolled toward him slowly, no logos, no plates visible.

Every instinct Scott had screamed at the same time.

Wrong.

He turned to run.

He didn’t make it three steps.

The van door slammed open before it had even stopped. Briggs hit him from behind. Full-speed tackle. Scott’s face slammed into asphalt. Pain exploded. Air rushed out of his lungs.

Holt’s boot caught him twice in the same side Henry had been kicked. Sharp, precise blows. Not wild. Practiced.

A black bag came down over his head.

Zip ties bit into his wrists.

They dragged him across gravel and metal ridges into the van. Doors slammed. The engine roared.

The world became engine noise, the stink of oil and sweat and the hot cloth pressing against his mouth. Scott fought the urge to panic. He counted.

Right turn. Twenty seconds.

Straight. Two minutes.

Left. Three minutes.

The van drove for twenty minutes. Maybe twenty-five. Time blurred under the pain.

It stopped. Doors slammed open. Hands yanked him out, feet scraping over concrete. The air smelled damp and metallic. Somewhere, water dripped.

They shoved him down into a chair. Metal. Hard. Cold.

The bag came off.

A warehouse. High ceiling. Exposed pipes. Cracked floor with dark stains that might have been oil or something else. No windows. One visible metal door. A single bare bulb overhead.

And in front of him, arms crossed, face arranged in bored contempt:

Sergeant Dale Crawford.

“You’ve been asking a lot of questions,” Crawford said. “That’s a problem.”

Scott’s lip throbbed. He tasted blood.

“I’m just a hot dog vendor,” he said.

Crawford laughed, a short, ugly sound that bounced off the concrete walls.

“Hot dog vendors don’t visit old men in the hospital and tell them to look into cameras,” he said. “Hot dog vendors don’t make files labeled ‘evidence’ and tuck them into hidden folders.”

He held up Scott’s phone.

The screen glowed. The EVIDENCE folder sat open.

“You thought you were clever,” Crawford said. “You’re not the first to try. You won’t be the last. Most of them learn sooner.”

Scott said nothing.

Crawford started to pace around the chair. Slow, measured, like a man considering how much force to apply to a locked door.

“Who are you working for?” he asked. “Reporter? Lawyer? Somebody in Houston? FBI? Who?”

“Nobody sent me,” Scott said. “I saw what you did to Henry. I couldn’t just—”

The slap came from nowhere. Open palm. Hard enough to snap his head sideways and blur his vision.

“Don’t lie to me,” Crawford said. “You think I don’t know a setup when I see one?”

“Nobody sent me,” Scott repeated.

Crawford hit him again. Closed fist this time. His cheek exploded in pain.

“Who are you working for?” Crawford demanded.

Scott spat blood onto the concrete and lifted his head.

“I’m just a vendor,” he said. “Who watched you beat a seventy-one-year-old man because he was two hundred dollars short. You think that’s going to stay secret forever?”

Crawford stopped pacing.

He studied Scott’s face for a long moment. His eyes searched for cracks in the story, openings, tells.

He didn’t find any.

He turned to Briggs.

“What do you think?” Crawford asked.

Briggs shrugged. “Could be some idiot trying to play hero,” he said. “Some people are that dumb. Or he could be something else.”

Crawford knelt until he was eye-level with Scott.

“Here’s my problem,” he said quietly. “If you really are just a vendor with more courage than sense, I can make you disappear tonight and it’ll be a two-paragraph story in the local paper. ‘Vendor found dead off county road. No foul play suspected.’ Happens all the time. Nobody loses sleep.”

He stood and began to pace again.

“But if you’re connected to something bigger,” he continued, “if you’ve got a badge tucked away somewhere, or friends in Houston, or somebody in Washington watching… you vanish and I’ve suddenly got people crawling all over my life. That’s messy.”

He stopped behind Scott’s chair, out of his sightline.

“So here’s what’s going to happen,” he said. “You’re going to leave Hartfield tonight. You’re going to delete every file you’ve collected. You’re going to forget Main Street exists. And if I ever see you near this town again…”

He leaned down until his mouth was inches from Scott’s ear.

“We’ll have a different conversation,” he said. “And it won’t involve this much restraint.”

“And if I say no?” Scott asked.

Crawford smiled.

“Then we find out what you really are,” he said.

The beating lasted twelve minutes.

Ribs. Kidneys. Thighs. Nothing vital. Nothing that would show too clearly through a shirt. They had experience. Hurt him, don’t kill him. Pain without permanent evidence. Make him remember without leaving a body that would draw questions.

When they were done, Scott could barely breathe.

Crawford stood over him, breathing hard.

“Leave tonight,” he said, voice flat. “Or don’t leave at all.”

Bag over his head. Van. Gravel under his back. Cold air.

They dumped him on the side of a county road outside the Hartfield city limits just after three a.m.

The van’s engine noise faded into the distance.

Scott lay there for a long time, watching the stars swirl overhead, trying to remember how to pull air into his battered lungs. His ribs screamed. His face throbbed.

He was alive.

More than he’d expected, if he was honest.

Slowly, he lifted one shaking hand to his shoe. His fingers fumbled with the lining, found a hidden flap, and pried it open.

A flat black rectangle slid out. Backup device. Secondary phone. They’d taken the obvious one and missed the other.

He thumbed it on. The screen lit his bruised face in a faint glow.

He typed a single message with stiff fingers.

Cover intact. Moving to Phase Two.

He hit send.

Then he let the phone fall onto his chest and closed his eyes.

Somewhere in the dark, a coyote cried.

Sunday morning, gray light filtered through the blinds of a different apartment on a different side of Hartfield.

Scott shouldn’t have been in the city.

Crawford had made that clear.

Briggs and Holt had underlined it with their boots.

But leaving wasn’t an option anymore. Not after Henry. Not after what had happened next.

He sat on the edge of a cheap mattress, ribs taped tight, every movement a small act of will. His entire body hurt. His face looked like someone else’s in the bathroom mirror.

The burner phone on the table buzzed.

He picked it up.

Tyler’s voice came through, ragged.

“Elena’s gone,” Tyler said. “Her neighbor found her this morning. They said it was her heart. ‘Natural causes.’”

Scott didn’t answer.

He didn’t have to see the death certificate to know what had really killed her.

Years of stress. Years of fear every time a patrol car slowed near her cart. Years of watching men in uniform decide who got to eat and who got to stand in the sun and hope.

And one last day when Crawford leaned over her cart and threatened to make her disappear.

Her heart had been patching itself together for a long time. It finally tore.

On paper, it would be a medical problem. In reality, it was a slow-motion homicide.

Scott sat in silence after Tyler hung up.

He pictured Elena placing a coffee in his hand on his first day. Elena laughing at his clumsy attempt at Spanish. Elena telling him, Be careful around here.

He opened his laptop with fingers that still hurt from blocking blows.

He stared at the EVIDENCE folder for a long moment.

Then he made a call.

The number went to a secure line at an office in Houston, Texas.

“Marshal Service, public corruption unit,” a voice said on the other end. “Lieutenant Whitmore.”

“It’s Davidson,” Scott said. “Phase Two. It’s time.”

Eight a.m. Monday, the Houston skyline gleamed under a less cruel sun than Hartfield’s.

The FBI field office on the west side of the city looked like any other modern federal building—glass, steel, and security checkpoints.

Scott walked through the front doors.

The guard on duty looked up, saw the bruised face, and stiffened. Then his expression shifted.

“Morning, Deputy,” he said. “Rough weekend?”

“Something like that,” Scott said.

He swiped his badge at the checkpoint.

Not the vendor permit.

The real one.

U.S. MARSHALS SERVICE.

The elevator doors closed, muffling the faint murmur of tourists asking about directions to other floors.

Fourth floor. Conference Room C.

Lieutenant Carl Whitmore was already there when Scott walked in. Fifteen years in public corruption. Gray hair at his temples. Calm blue eyes that had seen enough human behavior not to be surprised by much.

Scott sat down across from him, ribs protesting.

He took off his jacket.

He set his badge and ID on the table between them like a confession.

“Deputy U.S. Marshal Scott Davidson,” he said. “Hartfield operation, eighteen months. We’ve got enough.”

Whitmore looked at the bruises. He didn’t say, I told you to stay careful. He didn’t say, What did you do? He just nodded once.

“Show me,” he said.

Scott slid a stack of folders across the table. Then another. Then a drive.

“Crawford’s been running a protection racket on downtown Hartfield for at least three years,” he said. “We’ve confirmed fourteen vendors. Three hundred to five hundred a week each, cash. That’s conservatively fifty thousand a year, off the books.”

He opened the first folder.

“Bank records,” Scott said. “Crawford’s personal account. Eighteen months. Dozens of small cash deposits—fifty here, a hundred there. Always under the reporting limit. Different branches around the county. Classic structuring pattern. You overlay the dates with my videos…”

He slid over a chart.

“…and it lines up almost perfectly with collection days on Main Street.”

Whitmore studied the chart.

“Phones,” Scott said, handing him the next folder. “We got tower dumps for Crawford’s department-issued phone. It pings near Main Street every Friday afternoon. We compared that to my apron cam timestamps. Same time, same place.”

He pushed the drive forward.

“Footage,” he said. “Bodycam from three different federal recording devices. One on me. Two on other vendors we wired. Explicit demands. Explicit threats. Explicit acceptance of cash in exchange for ‘protection.’”

Whitmore flipped through some still images clipped from the videos. Crawford at Elena’s cart. Crawford at Henry’s. Crawford taking money from Scott.

“And the assault?” Whitmore asked.

“Warehouse on the edge of town,” Scott said. “Friday night. I got a backup device in my shoe. Audio only. Twelve minutes. They didn’t find it.”

“Assault on a federal officer,” Whitmore said quietly.

“Yes, sir.”

“And Elena?” he asked.

Scott’s jaw tightened.

“Sixty-two,” he said. “Heart condition. Eleven years on Main. Crawford cornered her Friday and threatened her family. She died Sunday morning. On paper, cardiac arrest.”

“Technically not chargeable as murder,” Whitmore said.

“No,” Scott said. “But it goes in the narrative. It’s part of the story of what he did.”

Silence settled over the table for a moment.

Whitmore leaned back, still looking at Scott.

“Eighteen months undercover,” he said. “You get beaten half to death, you watch a veteran get kicked in the street, and an innocent woman dies. I’m going to ask you something you probably don’t want to answer.”

“Was it worth it?”

Scott looked past him for a moment, eyes unfocused. Henry on the concrete. Elena pressing a coffee into his hand. The word SNITCH dripping red down Tyler’s ruined stand.

“Elena Vargas was sixty-two years old,” he said finally. “She had three children, four grandchildren, and a corner of Main Street she made feel like home. She warned me to be careful the same week she made me feel welcome.”

He looked Whitmore in the eyes.

“Crawford killed her without ever touching her,” he said. “If this ends with him in handcuffs instead of on Main Street, then yes. It was worth it.”

Whitmore nodded. “Then let’s end it.”

He reached for another file.

“There’s a problem,” he added.

“Of course there is,” Scott said, weary but not surprised. “What kind?”

“Every time we moved in Hartfield for the last six months,” Whitmore said, “Crawford moved first. When we floated the idea of approaching vendors directly, he showed up on Main Street twenty-four hours later making fresh threats. When you scheduled that Friday meet with your ‘source’…”

“The ambush,” Scott said.

Whitmore nodded. “Somebody inside our side is feeding him information. We have a mole.”

Scott felt cold crawl up his spine.

“Who?” he asked.

“That’s what we’re going to find out,” Whitmore said.

They spent the next six hours in that room.

They went over every operation, every leak, every time Crawford had seemed just a little too prepared. They built a timeline on a whiteboard. March—plan to flip Elena as a witness. Forty-eight hours later, Crawford threatened her on the record. April—financial monitoring initiated. Three days later, Crawford changed his cash deposit patterns.

“Who knew?” Scott kept asking.

Each time, the list was the same.

“You. Me. Assistant U.S. Attorney Collins. Surveillance coordinator. Task force agents on rotation.”

They pulled the surveillance logs.

One name appeared over and over on the line that mattered.

Agent assigned: R. COLE.

Special Agent Raymond Cole. Fourteen years in the FBI. Clean jacket. Good performance reviews. No formal complaints. Transferred to the Hartfield public corruption task force six months earlier.

“Pull his financials,” Whitmore said.

They did.

The pattern was like a ghost echo of Crawford’s. Smaller amounts. More sporadic. Eight thousand dollars in unexplained cash deposits in six months, always under the reporting threshold, always at different branches around Houston and Hartfield.

“Crawford wasn’t just pressuring vendors,” Scott said. “He bought himself an inside man.”

“Looks that way,” Whitmore said. His voice went hard. “Cole knows everything. Witness names. Operation plans. Evidence locations. If he figures out we know, he tells Crawford, and this whole thing burns down.”

“So we don’t let him know,” Scott said.

“How?” Whitmore asked.

“We give him something to leak,” Scott said. “Something that makes Crawford relax.”

Whitmore rubbed a hand over his jaw.

“Go on,” he said.

“We feed Cole a story that Washington’s pulling the plug,” Scott said. “Resources being reallocated. Hartfield getting rolled into another jurisdiction. Tell him we’re freezing operations and transferring me out.”

“Crawford hears that…” Whitmore said slowly.

“…he thinks the heat’s gone,” Scott finished. “He goes back to Main Street like he owns it again. Drops his guard.”

“And in the meantime?” Whitmore asked.

“In the meantime,” Scott said, “I go back to Main Street.”

“You think he won’t try again?” Whitmore asked. “He already tried to scare you out of town. Next time, he aims higher.”

“Next time,” Scott said, “I won’t be alone.”

He pointed to the map of downtown Hartfield taped to the wall.

“Agents in plain clothes at every corner. Surveillance van two blocks out. Arrest teams on standby. If Cole tips him off and they stay away, we move on Cole instead. Either way, someone goes down.”

Whitmore was quiet for a long time.

“There’s another clock,” he said finally. “Rebecca Torres at the Houston Tribune. She’s been working her own angle on Hartfield for eight months. She’s ready to go to print. We asked her to hold for as long as we could.”

“How long?” Scott asked.

“Forty-eight hours,” Whitmore said. “Maybe less. Once that story hits, Crawford runs. He’s got contingency plans. Stashes. Friends. You won’t see him on Main Street again.”

Scott glanced at the wall clock.

“Then we move in forty-eight hours,” he said.

He picked his badge up off the table, closed his fingers around it, and headed for the door.

“Scott,” Whitmore said.

He stopped.

“Elena died because someone in this building betrayed her,” Whitmore said. “Don’t forget that.”

“I won’t,” Scott said.

“And don’t die trying to make it right,” Whitmore added.

Scott didn’t answer.

He walked out.

Wednesday, 2:00 p.m.

Main Street, Hartfield, Texas, looked like any other hot afternoon.

Office workers in rolled-up sleeves bought cold drinks. Tourists paused in patches of shade. A kid on a bicycle wove through pedestrians like he was immortal.

If you didn’t know what you were looking for, nothing seemed unusual.

If you did, the pattern was glaring.

A woman in a sundress leaning against a lamppost, eating a taco a little too slowly, eyes moving just a bit too much.

A man in a polo shirt on a nearby bench, newspaper open, gaze flicking above the fold more often than it dropped to the print.

A couple with a camera near Elena’s old spot, pointing the lens at buildings more than at each other.

Plainclothes FBI. U.S. Marshals. Task force members disguised as ordinary Texans.

Two blocks away, a surveillance van idled, unmarked, windows dark.

On side streets, engines hummed quietly in three separate vehicles. Arrest teams in place. Radios on low.

At the corner of Main and Fifth, the hot dog cart was back.

Same stainless-steel shine. Same setup. Same steam rising off the warmer.

The vendor was the same man.

Scott’s bruises had faded to yellow and brown, but the stiffness in his movements gave them away if you knew what to look for. He set a bun in the steamer. He squeezed mustard onto a dog. He handed a soda to a customer who had no idea the man ringing him up had a badge under his apron and a wire under his shirt.

Word traveled along Main Street faster than the sound of traffic.

The vendors saw him first.

Tyler, operating from a borrowed folding table and borrowed crates now, froze in the middle of a sale. His mouth fell open. The empanada woman crossed herself.

A murmur moved along the block.

The Black vendor’s back.

The one Crawford said was gone.

The one everyone quietly feared they’d never see again.

It took less than an hour for Crawford to hear.

When he did, something inside him blew.

He pulled out of the Hartfield PD parking lot like the cruiser had rockets on it. He parked crooked in the familiar no-parking zone. He got out of the car fast for the first time in weeks.

He didn’t look around at the agents in the crowd.

He saw only the hot dog cart and the man behind it.

He stormed across the sidewalk, jaw clenched, hands balled into fists.

“You should be gone,” he said, stopping three feet from Scott. “Or dead. Why are you here?”

Scott held his gaze.

“I’m here because Elena isn’t,” he said.

Something flickered in Crawford’s eyes. Just for a second.

“The old woman had a heart attack,” he said. “Natural causes. Nothing to do with me.”

“You terrorized her until her heart gave out,” Scott said. “You threatened to make her disappear. You killed her without any of the paperwork.”

Crawford stepped closer. His right hand drifted toward his belt.

“You have three seconds to get in your car and drive away,” he said, voice low. “Or that night in the warehouse is going to feel like a warm-up.”

Scott didn’t move.

“Or what?” he asked. “You’ll beat me again? Like you beat Henry? Like you scared Elena into her grave? Like you’ve been bleeding everyone on this street for three years?”

Crawford’s fingers wrapped around the grip of his gun.

“Last chance,” he said. “Walk.”

Scott took a breath.

“Sergeant Dale Crawford,” he said, voice steady, “you’re under arrest for extortion, conspiracy, and assault on a federal officer.”

For a heartbeat, the entire street went silent.

Then someone laughed.

Crawford.

“You?” he said. “You’re a hot dog vendor. You don’t arrest anyone.”

Scott reached into his apron.

He pulled out a badge.

Sunlight flashed off the metal.

“Deputy U.S. Marshal Scott Davidson, public corruption unit,” he said. “I’ve been recording you for eighteen months.”

Color drained from Crawford’s face. The gun in his hand trembled.

“That’s not possible,” he whispered.

“It’s very possible,” Scott said. “And it’s done.”

Somewhere behind Crawford, a voice shouted, “Now!”

Agents moved.

Two from the left, two from the right. Guns drawn, vests obvious now, badges up.

On the far side of the street, Briggs and Holt were already on the ground, faces pressed into hot concrete, hands cuffed behind their backs.

Crawford saw them out of the corner of his eye.

Panic replaced anger.

He jerked the gun upward.

Scott didn’t reach for his weapon.

He didn’t have to.

Two sharp cracks split the air.

They weren’t from Crawford’s gun.

Crawford jerked as a taser hit him from behind, muscles snapping tight. His gun flew from his hand and skidded across the sidewalk. He hit the pavement on his stomach, arms flailing.

Agents crashed down on him. Hands yanked his arms behind his back and locked them into cuffs.

He lay face-down on Main Street, cheek pressing against the same concrete Henry’s blood had dried on. For the first time, he looked small.

“You’re dead,” he spat, words distorted by the concrete. “You’re all dead. You have no idea who owes me favors.”

Scott walked up until his shoes were inches from Crawford’s face.

“Elena Vargas was sixty-two,” he said quietly. “She stood on this corner for eleven years. She had three children and four grandchildren.”

He crouched slightly.

“You’re going to have time to think about that,” he said. “A lot of it.”

They hauled Crawford to his feet and pushed him into the back of a federal vehicle.

The vendors on Main Street watched.

Some with open satisfaction. Some with quiet disbelief. Some with fear, because they knew that putting one man in cuffs didn’t erase the system that had allowed him to operate.

Scott watched the car turn the corner and disappear.

Then he looked at the patch of sidewalk where Elena’s cart had stood.

Nothing marked it now. No plaque. No flowers. Just a slightly cleaner square of concrete where somebody had washed away the chalk the kids drew last week.

He stood there for a long second, apron still on, badge cooling against his chest.

Justice had finally shown up on Main Street.

It hadn’t come fast enough.

One week later, the case had a name.

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA v. DALE R. CRAWFORD.

Case No. 4:24-CR-000892, filed in the United States District Court for the Southern District of Texas.

Three counts of Hobbs Act extortion. One count of conspiracy. One count of assault on a federal officer.

Maximum exposure: forty-five years.

Co-defendants: Officers Dennis Briggs and Wayne Holt of the Hartfield Police Department. Special Agent Raymond Cole of the FBI, charged with obstruction and accepting bribes. Deputy Chief Harold Vance, suspended pending investigation. One city inspector, Gerald Nolan, picked up by state authorities on related charges.

Through his attorney, Crawford denied everything.

“These charges represent federal overreach targeting a decorated law enforcement officer,” the statement read. “Sergeant Crawford has served Hartfield honorably for nearly two decades. We look forward to clearing his name.”

The union echoed the statement. They usually did.

Rebecca Torres’s story hit the Houston Tribune’s front page the same day the indictment went public.

EIGHTEEN MONTHS OF TERROR ON MAIN STREET, the headline read.

Within a week, the article had been read by two million people online. National outlets picked it up. Cable news ran segments with grainy video of Crawford collecting cash, of Henry on the ground, of Elena smiling behind her cart in a photo her family had given the paper.

City Hall in Hartfield called for an “independent review” of downtown patrol practices.

Whether that review would be anything more than a press release was another question entirely.

Henry Dawson left the hospital after three weeks.

He walked slower. He moved stiffer. His hands shook worse than before.

But on Monday morning, he rolled his pretzel cart back to the corner of Main and Fifth.

He was there when office workers came by for coffee. He was there when school kids passed on their way home. He was there when the sun beat down and when it slipped behind the buildings.

The bruise on his cheek had faded.

The mark it left on him hadn’t.

Tyler got a new cart.

Vendors from three blocks pooled money. A local church chipped in. A small restaurant donated their old wheels. By Friday, he was back under his usual tree, fruit stacked high again, trying to believe it would be different this time.

At Elena’s old spot, her family set up a small table on a Saturday morning.

They brought photos. Flowers. A framed image of Our Lady of Guadalupe. People from Main Street came by all day. They left candles. Notes. Stories.

Three of Elena’s children took turns speaking about their mother.

Four grandchildren laid roses down on the square of concrete where her cart had stood for eleven years.

Scott came.

He stood under the shade of a tree across the street. He didn’t introduce himself. He didn’t speak.

After the crowd thinned, he walked over to the small makeshift memorial and placed a single white carnation among the other flowers.

Then he left.

Later that week, he drove to a cemetery on the edge of town.

The dirt on the new grave was still fresher than the plots around it. The temporary marker read ELENA VARGAS, 1962–2024.

He stood there with the Texas wind tugging at his shirt.

“I should have ended this before he got to you,” he said quietly. “I did everything by the book. That doesn’t always mean it’s enough.”

He left another flower and walked back to his car as the sun went down.

Back in Houston, the walls of Scott’s office told a story.

Two photographs hung side by side.

On the left, his younger brother, Jameson Davidson. Twelve years earlier, Jameson had been pulled over fifty miles outside Dallas. The official story said “confused commands” and “tragic misunderstanding.” Jameson had been unarmed. Scott had joined the Marshals a year later.

On the right, a picture of Elena that someone on Main Street had given him. She was laughing, head thrown back, hand up like she was scolding the camera.

Lieutenant Whitmore stopped in the doorway one afternoon and studied the photos.

“You did everything you could,” he said.

“I did everything I was supposed to do,” Scott said. “That’s not the same thing.”

“No,” Whitmore agreed. “It’s not.”

He looked at the badge on Scott’s desk.

“That thing doesn’t make you untouchable,” he said. “It makes you responsible. Some days that’s the heaviest part.”

He left Scott alone with the pictures and the quiet thrum of the office.

Outside, Houston went on.

People drank coffee. Went to work. Commuted on I-10. Argued with their kids about homework. Lived lives that would never intersect with a hot dog cart on Main Street in Hartfield, Texas.

On that corner, the air felt a little lighter.

The fear didn’t vanish overnight. Habits born in terror don’t die fast.

But when patrol cars cruised by now, drivers looked straight ahead. They didn’t slow. They didn’t lean on the horn.

Vendors started talking again.

Laughing.

Sharing coffee.

Telling stories that didn’t always end in warnings.

There were still problems.

There always would be.

But one man who had turned his badge into a weapon was gone.

And the quiet, stubborn fact of it settled into the cracks of Main Street like the first drops of rain before a long-promised storm.

News

I was at TSA, shoes off, boarding pass in my hand. Then POLICE stepped in and said: “Ma’am-come with us.” They showed me a REPORT… and my stomach dropped. My GREEDY sister filed it so I’d miss my FLIGHT. Because today was the WILL reading-inheritance day. I stayed calm and said: “Pull the call log. Right now.” TODAY, HER LIE BACKFIRED.

A fluorescent hum lived in the ceiling like an insect that never slept. The kind of sound you don’t hear…

WHEN I WENT TO MY BEACH HOUSE, MY FURNITURE WAS CHANGED. MY SISTER SAID: ‘WE ARE STAYING HERE SO I CHANGED IT BECAUSE IT WAS DATED. I FORWARDED YOU THE $38K BILL.’ I COPIED THE SECURITY FOOTAGE FOR MY LAWYER. TWO WEEKS LATER, I MADE HER LIFE HELL…

The first thing I noticed wasn’t what was missing.It was the smell. My beach house had always smelled like salt…

MY DAD’S PHONE LIT UP WITH A GROUP CHAT CALLED ‘REAL FAMILY.’ I OPENED IT-$750K WAS BEING DIVIDED BETWEEN MY BROTHERS, AND DAD’S LAST MESSAGE WAS: ‘DON’T MENTION IT TO BETHANY. SHE’LL JUST CREATE DRAMA.’ SO THAT’S WHAT I DID.

A Tuesday morning in Portland can look harmless—gray sky, wet pavement, the kind of drizzle that makes the whole city…

HR CALLED ME IN: “WE KNOW YOU’VE BEEN WORKING TWO JOBS. YOU’RE TERMINATED EFFECTIVE IMMEDIATELY.” I DIDN’T ARGUE. I JUST SMILED AND SAID, “YOU’RE RIGHT. I SHOULD FOCUS ON ONE.” THEY HAD NO IDEA MY “SECOND JOB” WAS. 72 HOURS LATER…

The first thing I noticed was the silence. Not the normal hush of a corporate morning—the kind you can fill…

I FLEW THOUSANDS OF MILES TO SURPRISE MY HUSBAND WITH THE NEWS THAT I WAS PREGNANT ONLY TO FIND HIM IN BED WITH HIS MISTRESS. HE PULLED HER BEHIND HIM, EYES WARY. “DON’T BLAME HER, IT’S MY FAULT,” HE SAID I FROZE FOR A MOMENT… THEN QUIETLY LAUGHED. BECAUSE… THE REAL ENDING BELONGS TΟ ΜΕ…

I crossed three time zones with an ultrasound printout tucked inside my passport, my fingers rubbing the edge of the…

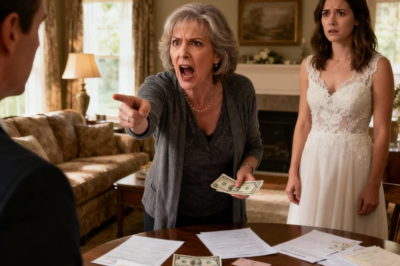

“Hand Over the $40,000 to Your Sister — Or the Wedding’s Canceled!” My mom exploded at me during

The sting on my cheek wasn’t the worst part. It was the sound—one sharp crack that cut through laughter and…

End of content

No more pages to load