The first command cracks through Central Park like a gunshot.

“Get your hands where I can see them. Now.”

The voice is rough and jagged, already sure it will be obeyed. It rides the quiet Sunday afternoon air over the clipped grass and winding paths of New York City’s most famous park, slicing through the murmur of tourists and the low rush of traffic on Fifth Avenue.

General James Thorne does not startle.

His hand pauses instead, the charcoal pencil arrested mid-stroke above the creamy page of his sketchbook. The lines of a bird’s wing hang unfinished beneath his fingers, a frozen moment of grace interrupted by something uglier.

He lifts his head.

Two NYPD officers stand in front of him on the paved path, their blue uniforms and black utility belts stark against the pale winter light. One is older and thick through the middle, his bulletproof vest pushing the fabric of his shirt into sharp folds. His face looks carved into a permanent sneer, deep grooves dragging his mouth downward. The other is young and lean, still narrow at the shoulders, his jaw too smooth to fit the hardness of the uniform. His eyes are wide in a way that says he hasn’t yet learned how to hide what he feels.

Thorne sits on a park bench near the north end of Central Park, a short walk from the Harlem Meer and a stone’s throw from the American flag flapping above a nearby playground. He wears a plain gray hoodie, the hood down. Worn black track pants. Running shoes that have seen better days. His skin is the dark brown of coffee left to cool, his hair cropped close to his scalp. A Black man in casual clothes, alone on a bench, drawing a bird.

For one of the officers, that is enough to be suspicious.

The older cop steps closer, his boots crunching on a patch of old snow. His name tag reads T. MILLER. His right thumb pops the snap on his holstered service weapon with a practiced flick, the sound small but precise, like the opening move of a game he expects to win.

“I said, hands up,” Sergeant Miller repeats, slower this time, as if addressing someone hard of hearing or deliberately defiant.

Thorne’s gaze flickers briefly to the loosened holster strap, then back to the officer’s face. He lays the pencil down beside him on the bench, gently, like setting aside a fragile bone. Then he raises his hands to shoulder height, palms facing out, fingers spread wide. The posture is familiar, muscle memory etched into him from a lifetime of warnings.

Comply. Always comply.

It is the first rule of survival his mother drilled into him in Birmingham, Alabama, decades before four silver stars were pinned to the shoulders of his U.S. Army dress uniform. Before the Pentagon briefings. Before the secure motorcades and foreign war zones. Back when the danger came not from distant enemies but from men who wore badges in his own country.

“Is there a problem, Officer?” he asks.

His voice is deep and measured, a baritone that has filled operations tents in Afghanistan and briefing rooms in Washington, D.C. It’s a voice trained for command, for ordering battalions into motion, for delivering calm clarity when chaos presses in from every direction. Today, in a park in Manhattan, he uses it for something much smaller and somehow far more exhausting:

De-escalation.

Miller’s lip curls. Up close, Thorne notices broken capillaries spiderwebbing across the man’s cheeks, a nose that’s been broken more than once, eyes the bloodshot red of cheap beer and short sleep.

“Yeah, there’s a problem,” Miller says. “You’re the problem. Loitering, vagrancy, take your pick.”

Thorne keeps his hands steady, his voice even.

“I am sitting on a public bench,” he says. “In a public park. During daylight hours. Could you please clarify which statute I am violating, Sergeant?”

The question is precise and clinical, the syllables clipped. He knows exactly what he’s saying and exactly how it will land.

Miller’s face darkens, as if someone nudged a dimmer switch. The casual disdain hardens into something hotter and more personal. This is not the stammering apology, the flustered excuses he is used to hearing when he barks orders at strangers whose only crime is existing in the wrong skin in the wrong place.

“You think you’re smart?” Miller says, stepping closer until the sour tang of coffee and old sweat reaches Thorne’s nose. “We got ourselves a park lawyer here.”

His shadow falls across the open sketchbook in Thorne’s lap, eclipsing the half-finished drawing of a blue jay. The bird’s head is almost complete, the fine lines of its crest and beak rendered with careful patience. The tail feathers trail off into emptiness, the strokes still light and tentative.

The younger officer shifts his weight awkwardly from one foot to the other. His name tag reads DAVIS. His hands hover near his own duty belt, not quite touching his holstered weapon, not quite loose at his sides. His gaze flicks from his partner’s back to the man on the bench, to the sketchbook, to the pond beyond where a few ducks paddle through a skim of ice.

He sees, with painful clarity, a citizen drawing quietly in the park.

He hears a man asking a reasonable question in a calm tone.

In his gut, a knot tightens. This is not what they’re supposed to be doing. Not what he imagined when he put on the NYPD uniform for the first time six months ago in front of his proud parents in Queens, his mother crying into a wrinkled tissue as the bagpipes played.

“Sir,” Davis begins, his voice hesitant, the word catching on the cold air. “Maybe we should just ask him what he’s doing out here. It’s—it’s Central Park. People sit.”

“I know what he’s doing,” Miller snaps, not looking back, his stare still locked on Thorne like a dog on a bone. “He’s casing the place. Or waiting for a deal. That right? You waiting for something to go down?”

Thorne doesn’t answer the accusation. He lets it drift away like breath in the cold. His gaze slides past Miller’s shoulder to the small pond a short distance away, where the surface glitters dully under the thin afternoon sun.

He can almost see her there.

Eleanor.

Her wool coat buttoned to her throat, bright red scarf tucked around her neck, hair peeking from beneath a knit cap. Hands cupped, tossing bits of bread to the ducks, laughing as they scramble and splash. She loved this park—its messy beauty, its mix of tourists and locals, joggers and nannies and old men playing chess. She loved how trees and water and sky could exist in a city of steel and glass and sirens.

In the three months since cancer took her, this stretch of Central Park has become his sanctuary by inheritance. He comes here to remember her laughter, the way her hand felt curled around his arm, the way she tilted her head when she studied a new bird on a branch.

He took up sketching because of her. Because she believed that noticing beauty was an act of defiance against cruelty. Because drawing the world forced you to really see it.

The charcoal under his fingernails is a quiet tribute. A way to keep her close.

His rank, his medals, the Pentagon offices, the war plans and strategy sessions—all of that feels a world away from this bench. Here, in this moment, he is just James. A widower trying to breathe.

And now that fragile peace is being shattered.

“Stand up. Slowly,” Miller orders.

Thorne stays seated, hands still raised and empty.

“Sergeant,” he says, every syllable burnished smooth. “You have not articulated a reasonable suspicion of a crime. Under New York law, I am not obligated to comply with that order.”

He doesn’t raise his voice. He doesn’t lace it with anger. He speaks the language of the law the way he once spoke the language of battle plans—carefully, deliberately, aware that every word counts.

Each sentence is a stone laid in a wall between him and the other man’s temper.

For Miller, it’s gasoline on dry brush.

He moves in a blur of blue fabric and bulk, closing the distance in two heavy steps. His hand fists in the front of Thorne’s hoodie and yanks him upward. Thorne’s body rises easily; years of standing at attention and leading PT at dawn have left his posture straight and his muscles responsive, even in grief.

The sketchbook tumbles from his lap, landing open-spined on the patchy grass beside the bench. The page with the blue jay flutters, then lies still, pale against the dark, damp earth.

“You have a lot of nerve,” Miller hisses, his face inches from Thorne’s. His breath is hot and sour. “I am the law here. You understand me? I say stand, you stand. I say jump, you ask how high. That’s how this works.”

From behind, Davis watches the encounter veer over a line he can feel but not quite name. At the Academy in upstate New York, they drilled de-escalation techniques into him. Talk low. Keep your distance. Listen. Build trust.

This—this is none of that.

This is domination. Raw and ugly.

The man in the gray hoodie stands tall despite the fist twisted in his clothing, his back straight, his chin level. There is something in his eyes that unnerves Davis more than shouting would: a deep, contained calm, like the still center of a storm.

He shouldn’t be this calm, Davis thinks. Not with a cop’s fist in his shirt. Not with a gun inches away.

He opens his mouth.

“Sergeant, maybe we should—”

“Shut it, Davis.” Miller’s reply is a sharp crack in the air. He doesn’t look at his partner. “Watch and learn. This is how you handle trash that thinks the rules don’t apply.”

The word hangs there.

Trash.

Thorne’s eyes narrow almost imperceptibly. It’s a tiny shift, barely a tightening around the lids, but Davis sees it. A man like this doesn’t telegraph much. The fact that anything shows at all means the insult hit something deeper than pride.

General James Elijah Thorne is a master of control. He has stared down warlords in remote compounds, politicians in Washington, journalists with cameras, grieving parents in military hospitals. He has sat in the Situation Room beneath the West Wing and explained casualty projections to Presidents. He has sent young Americans into danger with a weight in his chest that never really goes away.

He will not lose his temper for this man.

He will not give him that victory.

Instead, he does what he learned to do on battlefields and in hearings before Congress:

He observes. He documents. He builds a record.

Miller. Sergeant T. Badge number—his eyes flick down briefly, memorizing the digits—714. Time: 1432 hours, Eastern Standard Time. Location: New York City, Central Park, north end, near the Harlem Meer. Two officers present. One hostile. One hesitant. Contact began with verbal order, escalated to physical grab without stated cause. Racially charged language.

The list begins in his mind, each detail a bullet point on an after-action report that has yet to be filed.

“Let’s see some ID,” Miller demands, shoving Thorne back a step and releasing his grip on the hoodie. The fabric stays wrinkled over Thorne’s chest like a fingerprint.

“I will not be providing identification at this time.” Thorne’s tone doesn’t change. “You have no legal cause to demand it, Sergeant.”

“I have all the cause I need,” Miller snaps.

His gaze drops to the sketchbook lying open on the ground. For the first time, he seems to see the drawing itself—the fine, deliberate lines of feather and beak, the way the charcoal shading suggests depth and movement. It doesn’t fit the picture in his head of a criminal waiting on a bench for a drug deal. It is patient, careful work. It suggests stability, education, time.

So he destroys it.

He lifts his boot. For a heartbeat, his sole hovers above the page, weight balanced, an executioner’s axe still at the top of its swing.

Then he brings it down.

The thick tread smashes into the center of the drawing, grinding the paper against the cold, damp earth. Charcoal smears outward in a sudden gray halo, obliterating the bird’s delicate lines in a violent blur. The sound it makes is soft but obscene, a ripping, tearing whisper as the page gives way under his weight.

He twists his heel, tearing through the paper until a jagged white scar splits the middle of the smudge.

“Just scribbles,” Miller says, stepping back, a small, satisfied smile on his face. “Garbage.”

For Thorne, that is the breaking point.

It is not the shove. It is not the word “trash.” It is not even the fist in his shirt.

It is the boot on his wife’s memory.

That page is the latest in a series of small, stubborn rituals he has built around his grief. The blue jay had perched on a bare branch outside the bedroom window three nights ago, its head cocked, watching him as he sat awake in the dark at three in the morning, unable to sleep in a bed that suddenly felt twice as large and half as warm. Eleanor would have whispered, “Look, Jimmy. Even the birds are checking on you,” and reached for her sketchbook.

He had taken her old set of charcoal sticks from her studio, cleaned off the dust, and tried to capture the bird’s fierce little stance. It was the first thing he had drawn in months that felt like it might be good enough to show her, if she were still here.

Now it’s a boot print and a smear.

A cold fire ignites low in his chest. It is not the hot, wild anger that makes hands curl into fists and voices rise. It is something denser and more controlled, a slow, relentless burn that fuels campaigns and reforms and wars that last longer than any one battle.

His face remains composed. The muscles around his mouth barely move. His shoulders stay loose. But behind his eyes, crystallized around that ruined sketch, a decision is made.

This will not end the way Sergeant Miller thinks it will.

“Turn around,” Miller barks, pulling a pair of handcuffs from the back of his belt. The metal clinks together, bright and cold in the mild winter air. “You’re coming with me. Resisting arrest. Disorderly conduct. Whatever sticks.”

“I am not resisting,” Thorne says softly. There is something new in his tone, something colder than calm. “I am bearing witness to your misconduct.”

He turns.

He clasps his hands behind his back, fingers interlacing automatically, the way they have done thousands of times at attention. He feels the steel bite into the tender skin at the base of his thumbs as the cuffs snap shut. He lets it happen.

He does not pull away.

The trap isn’t sprung yet. The jaws are still open. To snap closed, the sergeant has to step fully inside.

Davis watches in horror as his partner cinches the cuffs tighter than necessary, the thin chain rattling between Thorne’s wrists.

“Resisting?” Davis blurts. “Sergeant, he wasn’t resisting at all. This is—this is going to be a problem. The report—”

“The only problem is you, rookie,” Miller cuts in. “You don’t have the stomach for this job. Now shut up and call it in. Suspect in custody, possible narcotics, suspicious behavior, the usual. Don’t overthink it.”

He takes Thorne by the elbow, fingers digging into the muscle of his upper arm, and steers him away from the bench. Behind them, the ruined sketchbook lies open in the slush, the mangled bird staring up with one intact eye.

They walk across the grass toward the nearest paved path where their patrol car sits nosed up against the curb, lights off. As they move, the quiet choreography of a public spectacle begins to assemble around them, the way it always does in the age of smartphones.

A father holding a toddler’s hand slows, eyes widening as he takes in the sight of the handcuffed Black man being marched toward the car by a red-faced officer. Two tourists in bright winter jackets step aside, their conversation dropping midsentence. A teenager in a Brooklyn Nets hoodie raises his phone and starts recording, the camera following every step, his other hand stuffed deep in his pocket.

Miller feels the eyes on him and straightens his shoulders, puffing up. There’s a swagger in his stride now, an extra snap in his walk that says he’s performing for an audience.

Thorne feels something else entirely.

History.

He feels it like weight on his shoulders heavier than the kevlar vest he’s worn in war zones. He thinks of all the men and women whose names never made the news, who were grabbed, shoved, cuffed, and thrown into the back of cars on flimsy pretexts and flimsy reasons, if any were given at all. People whose only real offense was daring to exist in public while Black or brown.

He carries them with him in each step across the grass.

Today will be different, he tells himself, not as a wish but as an objective. Today, their story gets a different ending.

They reach the squad car, an NYPD cruiser with its blue-and-white paint dulled by salt and dirt. The words POLICE—NYPD stretch across the side, the City of New York shield beneath them. An American flag decal flutters in a nonexistent breeze on the rear window.

Miller pushes Thorne forward, chest hitting the cool metal of the hood. The impact is loud enough to draw a few more glances from passersby. The steel is cold against his cheek. He smells the faint tang of oil and exhaust baked into the paint.

The public humiliation is complete. That’s part of the ritual. Make the suspect small. Make him visible. Make sure everyone knows who is in charge.

“All right, Mr. No-ID,” Miller says, patting down Thorne’s jacket with short, rough motions. “Let’s find out who you really are.”

His hand thumps against keys in one pocket, a folded scrap of paper in another. Then his fingers pause over the inner left breast pocket where the fabric bulges slightly.

Thorne can feel the outline of his wallet there, the familiar rectangle warmed by his body heat. He rarely carries it in casual clothes, but today he’d come straight from a morning meeting in Midtown with a defense contractor. Old habits die hard. He carries his military ID in it, a small piece of plastic that opens doors all over America and beyond.

A switch flips inside him.

Observation time is over.

“Sergeant Miller,” he says quietly.

His voice cuts across the chatter of the park, the distant honk of taxis, the rustle of trees. It is not loud, but it has weight. It is the voice he uses when he needs a room full of colonels and cabinet secretaries to stop bickering and listen.

Miller’s hand pauses on the wallet.

“My name is General James Thorne,” he continues, each word as flat and cold as the hood under his cheek. “United States Army. You are currently detaining a four-star general of the U.S. armed forces. I suggest you proceed with extreme caution.”

For half a second, the only sound is the wind scraping past bare branches.

Then Miller laughs.

It’s short and disbelieving, a bark torn from his throat.

“A four-star general,” he says. “In that outfit? On this bench? That’s the best one I’ve heard all week, man. You almost had me.”

“Check the wallet, Sergeant,” Thorne says. His tone doesn’t rise. If anything, it gets quieter. “That was not a request. That was an order.”

The word hangs there: order. Miller hears it the way it was meant to be heard, the way people in uniform hear it. There’s something in the other man’s voice that makes his skin prickle, some ingrained authority he can’t quite reconcile with the hoodie and the track pants.

Davis, standing a few steps away with the radio mic in his hand, feels a chill walk down his spine. The atmosphere around them has shifted. The air feels charged, like right before a summer thunderstorm breaks over the city.

The man on the hood is no longer just a calm, wronged stranger. There is a different presence in him now—something vertical, towering, like the steel ribs of a skyscraper.

Miller yanks the wallet from the pocket and flicks it open with a practiced thumb, already shaping a joke on his lips for whatever fake ID he expects to see.

The joke never makes it out.

Inside the clear plastic window is not a driver’s license or a flimsy fake printed on cheap cardstock. It is a Common Access Card—CAC—issued by the Department of Defense of the United States of America. Davis recognizes it instantly from the day a visiting Army officer came to speak at the Academy. The design is unmistakable: the eagle, the embedded chip, the crisp black text.

On the card is a photograph of the man currently pressed against the NYPD cruiser’s hood. In the picture, he wears a U.S. Army dress uniform: dark blue jacket, numerous ribbons in neat rows on his chest, the small U.S. flag patch on his shoulder.

And above his name, on his shoulders in the photograph, are four silver stars.

General James E. Thorne.

The world tilts.

The sounds of Central Park—kids laughing, a dog barking, ice clinking in a vendor’s cart—fade into a distant, muddled roar in Miller’s ears. His vision tunnels. The leather of the wallet feels slick in his suddenly clammy hands.

He has just assaulted and illegally detained one of the most senior military officers in the United States of America. A man who probably has the Secretary of Defense in his contacts. A man whose calls get answered on the first ring in Washington.

Davis steps closer, eyes wide, drawn as if by gravity to the ID card lying open on the hood.

He sees it all at once.

The posture. The way the man moved—controlled, measured. The way he spoke—like someone used to being listened to, not intimidated. The calm under pressure that never cracked. His brain rearranges the pieces. The casual clothes had thrown him. Everything else fits.

“Sergeant…” Davis manages, his voice hoarse. “Sergeant, you need to—uncuff him. Now.”

Miller doesn’t move.

His face has gone a chalky gray under his ruddy skin, as if someone drained all the color at once. The hand holding the wallet trembles. The ID card slips from between his fingers and clatters onto the hood beside Thorne’s cheek.

“I said uncuff him,” Davis says, more urgently this time. Panic climbs into his voice. “Sergeant, this is—this is a four-star general. This is—this is career-ending. You have to—”

“Do not touch me, Officer Davis,” Thorne says, cutting through the young cop’s words without raising his volume.

Davis freezes.

“Sergeant Miller will remove these restraints,” Thorne continues.

It is not a suggestion.

Miller flinches as if struck. The word “Sergeant” suddenly sounds very small next to “General.”

With fingers that don’t seem to want to obey him, he reaches for the key on his belt. The tiny piece of metal scrapes against the first lock twice before he manages to line it up properly. He fumbles, breathing too fast, the tips of his fingers numb. On the third try, the cuff pops open.

The second follows a moment later. The metal circles fall away from Thorne’s wrists with a soft, humiliating clink. He brings his hands around in front of him and rubs at the reddened skin, slow and deliberate, as if he has all the time in the world.

He doesn’t yell.

He doesn’t threaten.

He doesn’t need to.

The power dynamic in the park has flipped with the brutal swiftness of a vehicle rollover. One moment, Sergeant Miller is the voice of authority, performing for a scattering of New Yorkers with their phones held up. The next, he is a man who may have just detonated his own life on the hood of his own patrol car.

Thorne turns to face him fully.

Up close, with his back straight and his chin raised, he looks taller than he did on the bench. It’s not his actual height—though he is not a small man—but the way he occupies space, as if the ground itself acknowledges his presence.

“Sergeant Miller,” he says. “You have committed multiple crimes this afternoon. Assault. Unlawful detainment. Willful destruction of personal property. You initiated contact, escalated without cause, and used language that strongly suggests bias based on the color of my skin and the clothes I wear.”

Each sentence lands like a gavel strike.

Miller swallows, his throat working. He looks suddenly much older, his bravado melted away, leaving behind a man in a wrinkled uniform who cannot meet the general’s eyes.

Thorne reaches into his pocket and pulls out his phone. It’s a government-issued device, secure and encrypted, but outwardly it looks like any high-end smartphone glinting in the winter light.

He scrolls through his contacts. His thumb pauses on a name.

Robert Standish.

Governor of the State of New York.

He presses the screen.

The line rings once.

“Robert,” Thorne says when the call connects. “It’s Thorne.”

He doesn’t step away from the car. He doesn’t lower his voice. The teenager with the phone filming them now angles the camera slightly to include the general’s face and the phone pressed to his ear.

On the other end, there’s the sound of background noise quickly muting, a chair scraping back, a voice saying, “I need a minute,” and a door closing. Then the governor of New York speaks, his tone suddenly urgent.

“James? Is everything all right?”

“I am standing by the north entrance to Central Park,” Thorne says. “Near the Harlem Meer. I have just been assaulted and illegally detained by an officer of the New York City Police Department. I need State Police Internal Affairs on-site immediately. And I would like the Police Commissioner, or at the very least the city’s Chief of Police, present. Today.”

The silence on the other end is brief but telling.

“Jesus,” Governor Standish breathes. “Are you hurt?”

“I’m unharmed,” Thorne replies. “Physically. I cannot say the same for the credibility of this department.”

Davis hears the thin, high edge of panic in the governor’s answering “We’re on it. Stay where you are, James. Do not leave. I’ll have the superintendent dispatch units right now. And I’m calling the Commissioner myself. You’ll have everyone you want there in minutes.”

“I’ll be right here,” Thorne says.

He ends the call and slides the phone back into his pocket with the same tidy efficiency with which he holstered a sidearm for thirty years.

Around them, the little crowd that has gathered begins to pulse and shift as word spreads in hissing whispers. “Four-star general.” “Governor.” “Did he say Internal Affairs?” Phones multiply. A woman in a wool hat speaks rapidly into her camera for a livestream, her breath fogging in front of her face.

Miller looks like he might throw up.

Davis stands stiffly at parade rest without realizing it, his brain trying to catch up with the speed at which the ground has shifted under his feet.

Sirens arrive first as sound.

Not the familiar rising-falling chirp of city patrol cars, but a deeper, more authoritative wail that sends a different shiver through the air. The knot of onlookers parts instinctively as three dark blue sedans with State Police markings pull up to the curb, lights flashing red and white.

Men and women in dark suits step out—New York State Police Internal Affairs, the ones no cop wants to see on a call. Their badges flash on their belts, their faces set in grim lines. One of them, a tall Black woman with close-cropped hair threaded with gray, scans the scene with quick, assessing eyes and strides toward Thorne.

“General Thorne?” she says.

“Yes,” he replies.

“Captain Angela Ruiz, State Police Internal Affairs,” she says, holding out a hand. “We were told—well, we were told enough.”

He takes her hand briefly. Her grip is firm.

Behind them, another vehicle screeches to a stop—this one a black town car with a discreet light bar hastily slapped onto the dash. The door flies open and a man in a police dress uniform steps out, his hat crooked, his tie not quite straight, like he put everything on in a hurry. His face is flushed.

Chief of Police David Stevens, NYPD.

“General Thorne,” he calls, striding over, hand extended, voice booming in an attempt at warmth that sounds just a shade too loud. “This must be some terrible misunderstanding. If we could just—”

Thorne looks at the extended hand, then up at the chief’s face.

He does not take it.

“There is no misunderstanding, Chief,” he says. “There is a very clear pattern of abuse of power.”

Chief Stevens’ hand hangs in the air a moment longer before he drops it, his smile collapsing.

Thorne turns to Captain Ruiz.

“Captain, I am General James Thorne,” he says, his tone shifting into the precise cadence of an after-action briefing. “At approximately 1430 hours, I was seated on that bench” —he points— “engaged in the lawful activity of sketching. Sergeant T. Miller, badge number 714, and Officer Davis approached. Sergeant Miller initiated contact with an order to raise my hands. No crime or suspicion of crime was articulated. When I asked for clarification, Sergeant Miller escalated.”

He recounts everything.

Each word of Miller’s barked commands. The grab. The shove. The crushed sketchbook. The word “trash.” The tightening of the handcuffs. His own responses.

He gestures to the sketchbook in the grass, its pages bent and dirty, the drawing ruined but still recognizable beneath the smeared charcoal.

“Officer Davis’s body-worn camera should have recorded the interaction in full,” Thorne concludes. “I presume Sergeant Miller’s camera was also active.”

The captain turns to the two NYPD officers.

“Sergeant Miller,” she says. “Your camera. I’ll need the footage.”

Miller licks his lips.

“It, uh… it malfunctioned,” he says, the lie emerging slow and thick. “Battery issue. We—we’ve been having some problems with the units. I reported it last week.”

Captain Ruiz’s eyes narrow. They are the kind of eyes that have seen a hundred versions of this story.

“Did it,” she says flatly. “Officer Davis?”

Davis swallows. He can feel the weight of two worlds pressing down on him: loyalty to his partner, loyalty to the job, and loyalty to something deeper than both—what his father, a postal worker who never missed a day of route in thirty years, called simply “doing the right damn thing.”

“Yes, ma’am,” he says. “My camera’s on. It’s been on since we left the precinct. I have the full interaction.”

“Good,” Ruiz says. “Upload it.”

His hands shake slightly as he unclips the device and brings it to the captain. She connects it to a tablet and taps through menus, her jaw tightening as she waits for the video to load.

Chief Stevens stands to one side, trying not to look as though he’s craning to see the screen and failing. Miller stands rigid, eyes unfocused, breathing shallow. Sweat has begun to bead on his forehead despite the chill.

The grainy footage plays.

In real time, on the tablet’s screen, Miller’s harsh voice fills the little group. “Get your hands where I can see them.” Thorne’s calm response. The questions. The refusal to provide ID without cause. Miller lunging, grabbing, shoving. The boot coming down on the sketchbook, the smear of charcoal. The word “trash.”

Every ugly second is captured in crisp audio and video, the camera’s slightly wide angle making the drama look somehow both distorted and unforgivingly clear.

By the time the footage reaches the point where Thorne identifies himself as a general and the ID card hits the hood, Chief Stevens’ face has gone ashen. His mouth is set in a thin, bloodless line.

He sees not just a single PR disaster but a wave of them: headlines, protests, a mayor demanding answers, a governor on the phone, federal inquiries. He sees bodycam footage being played on cable news and streamed on social media with outraged commentary. He sees his own name attached to them all.

Captain Ruiz closes the video.

“Sergeant Miller,” she says. “Effective immediately, you are suspended from duty. Surrender your weapon and your badge.”

Miller stares at her as if he doesn’t understand the words.

“Captain, I—this is—he was—”

She doesn’t raise her voice.

“Now, Sergeant.”

Slowly, as if underwater, Miller reaches for the pistol on his hip. He unclips the retention strap, withdraws the weapon by its grip, and places it in the outstretched evidence bag held by one of Ruiz’s investigators. The sound of the metal settling is soft but final.

He pulls his badge from his chest, the NYPD shield that once filled him with so much pride, and hands it over. In the space of a few minutes, the trappings of his authority are gone.

“Chief Stevens,” Ruiz says, turning, her face expressionless. “Internal Affairs will be opening a broader investigation into Sergeant Miller’s conduct and the handling of prior complaints against him. It appears there may be more here than a single incident.”

She nods to one of her people, who steps aside and makes a call. Within minutes, a preliminary report comes back over encrypted channels—twelve civilian complaints filed in five years. Excessive force. Racial profiling. Verbal abuse. All marked unfounded. All signed off by the same supervising officer.

The enablers, the ones who denied and buried, are now squarely in the crosshairs too.

“Sergeant Miller,” Ruiz says, her voice even colder. “You will report to State Police headquarters tomorrow morning for a formal interview. Legal counsel is your right. Exercise it.”

Miller nods numbly.

He is no longer a predator prowling his beat.

He is prey.

Sirens rise again in the distance, a different tone this time: a rolling, layered escort wail. People on the sidewalk look up, recognizing the sound as something important. Television news vans, alerted by scanners and frantic assignment editors, begin to appear on the edges of the block, satellite dishes unfolding like metallic flowers.

A black SUV bearing the New York State seal pulls up behind the Internal Affairs vehicles. Governor Robert Standish steps out, wool overcoat flapping, his face a controlled mask of anger. A few reporters shout his name, but he ignores them, his eyes locked on Thorne.

“James,” he says, reaching him in a few quick strides. His voice is low, tight. “I am so damn sorry. This is unacceptable. Completely unacceptable.”

The microphones of half a dozen local and national news channels angle toward them from a distance, hungry.

Thorne gives a small nod.

“I appreciate your swift response, Governor,” he says. “I wish it had not been necessary.”

Standish turns, scanning the cluster of cameras now gathering at the edge of the scene. Years in politics have taught him to recognize when you cannot hide the fire—and when it’s smarter to step into the flames and try to control their direction.

As governor of one of the most watched states in the United States, he knows this story will not remain local. A four-star general of the U.S. Army, wrongfully detained in New York City’s Central Park by a cop with a history of complaints? It’s the kind of tale that travels fast from New York to Los Angeles and everywhere in between.

He takes a breath and raises his voice.

“Ladies and gentlemen,” he calls, addressing not just the crowd but the cameras, “as Governor of the State of New York, I am announcing an immediate, full-scale investigation into this city’s police department, to be led by the State Police and overseen by my office.”

The reporters surge forward, their camera operators trying to keep up.

“Effective immediately,” Standish continues, his tone brooking no argument, “Chief Stevens is placed on administrative leave pending the outcome of that investigation.”

Chief Stevens looks as if the ground has disappeared beneath him. Just like that, his decades-long career has been tossed into a storm.

“And as for Sergeant Miller,” the governor says, his gaze cutting to the officer being quietly escorted aside by two Internal Affairs agents, “he will face the full weight of the law. No one in this state is above accountability. Not even law enforcement. Especially not law enforcement.”

The words bounce across the park, captured and amplified by cameras, smartphones, and the endless echo chamber of social media.

He turns back to Thorne, voice dropping again.

“James, this isn’t a one-off problem. It’s rot. We both know it,” Standish says. “We’ve been talking around it for too long, waiting for commissions and reports that gather dust. I’m done waiting.”

He glances once more at the cameras, at the cluster of onlookers, at the teenager still filming with wide eyes, no longer pretending to be subtle.

“I’m forming a new statewide task force on police reform and accountability,” the governor says. “Real authority. Real teeth. With the power to set standards for every department in New York, from Buffalo to the NYPD. I need someone to lead it. Someone people will trust. Someone who understands discipline and chain of command, but also understands what it means to serve. I need you.”

Thorne looks past him, out at the park.

At the ruined sketchbook.

At Sergeant Miller, now slumped against the trunk of a tree, his world crumbling.

At Officer Davis, standing alone near the cruiser, his face pale, eyes troubled and honest.

He thinks of Eleanor. Of the mornings she used to tug him out of bed with a whisper of “Come on, let’s go see your city before the rest of it wakes up.” Of the fights they had over his schedule, over the demands of the Army, over the way the military always seemed to own more of him than she did.

He had dreamed, once he retired, of a different kind of life. Quiet mornings. Travel. Art classes. Maybe teaching at a university in someplace like Virginia or upstate New York.

Instead, on a random afternoon in Central Park, the country has tapped him on the shoulder again.

Another war. Different battlefield.

Not deserts or mountains this time, but precinct houses and training academies and union halls and city councils. A war for something harder to define than territory or resources.

A war for the soul of public service. For the idea that wearing a uniform—military or police—means you protect, not prey on, the people who pay for it with their taxes and their trust.

He hears his own voice in his memory, the things he’s told young officers and cadets over the years.

You don’t get to choose the fights that matter most. Sometimes they choose you.

He looks back at the governor.

“I accept,” General James Thorne says.

The words are simple. The ripple they send outward is not.

He turns to Officer Davis.

“Officer Davis,” he says.

The young cop straightens automatically.

“Yes, sir?” Davis says, the “sir” coming out before he can catch it, drilled into him by both academy instructors and the man’s clear rank.

“You showed integrity today when it would have been easier to stay silent,” Thorne says. “You kept your camera on. You spoke up. You didn’t falsify your report. The State of New York will need law enforcement officers like you if we’re going to fix this. But not here. Not in this culture.”

He glances at the governor.

Standish nods immediately, catching the cue.

“Son,” the governor says, “the New York State Police would be lucky to have you. If you want a transfer, we’ll make it happen. No retaliation. No games.”

Davis opens his mouth and closes it again. For a heartbeat, he looks like he might refuse, out of some warped sense of loyalty to the department whose uniform he wears. Then he thinks about the crushed sketchbook, the word “trash,” the way Miller dismissed him, the way Thorne looked at him—not with contempt, but with something like expectation.

“Yes, sir,” he says finally. “I—I’d be honored.”

Months later, winter has given way to spring, then to the thick, heavy air of a New York summer. The headlines and talk show segments and op-eds that exploded after “The Central Park General Incident,” as the tabloids dubbed it, have morphed into something deeper and less loud: policy drafts, legislative debates, budget fights, training overhauls.

General James Thorne stands at a podium in a large auditorium at the State Police Academy, the seal of the State of New York on the wall behind him and the American flag to his right. Above him, discreet but visible, a banner reads:

THE THORNE COMMISSION

POLICING WITH HONOR

Before him sits the first graduating class of cadets trained under the new statewide protocols his task force has shepherded into existence. Rows of tan and gray uniforms fill the seats, faces young and older, men and women, Black, white, Latino, Asian—a cross-section of the state they’ve sworn to serve.

Somewhere in the front row sits Trooper Daniel Davis, his uniform a different color now, his badge bearing the crest of the New York State Police.

The reforms the Commission pushed through have teeth. Mandatory bias training every year, not just once at the Academy and forgotten. Real, civilian-led oversight boards with subpoena power. Clear, strict use-of-force policies that leave less room for vague “feeling threatened” justifications. A centralized complaint database that can’t be quietly buried in a precinct captain’s drawer.

It hasn’t been easy.

Police unions have balked. Certain talk radio hosts have screamed. There have been heated hearings in Albany where Thorne sat, calm and implacable, as some lawmakers tried to poke holes in his proposals and found themselves skewered instead by his command of data and his unwillingness to soften the truth.

But today is not about the fights.

Today is about the future in these rows.

On a small easel beside the podium sits a framed drawing.

The paper is slightly warped, the fibers scarred. In the center, a blue jay perches on an invisible branch, its crest lifted, its eye bright and sharp. The torn section that once split the bird in half has been carefully, painstakingly mended by a professional conservator, the edges aligned and secured, the rip visible but no longer dominating the image. The charcoal smear from Sergeant Miller’s boot remains, faint but unmistakable, a dark bruise across the bird’s chest.

Thorne looks at it for a moment before addressing the cadets.

“This,” he says, nodding toward the frame, “is the first thing I ever drew in Central Park after my wife died. It’s also the first thing a cop smashed out of spite in front of me in that same park.”

A murmur ripples through the auditorium. They all know the story. They’ve seen the training video, watched the bodycam footage, read the case study in their ethics module. The Central Park incident has been incorporated into the Academy’s curriculum as a lesson in what not to do—and what must never be allowed to stand.

“You can still see the damage,” Thorne says. “The tear. The smear. You can also see the work that went into repairing it. A restorer spent hours cleaning and reinforcing the paper so it wouldn’t fall apart. She told me something that stayed with me.”

He pauses, letting the silence stretch just long enough.

“She said, ‘General, even when paper is patched, it keeps the memory of where it was torn. That scar is part of its story now. You can’t erase it. But you can make sure it doesn’t destroy the whole picture.’”

He lets that sink in.

“Our justice system is like that drawing,” he says. “Our policing is like that drawing. This country”—his voice thickens almost imperceptibly on the word, carrying with it the weight of decades in uniform under the American flag—“has tears in its paper. It has smudges. Ugly ones. Some of those scars run back centuries. We are not going to pretend otherwise.”

In the front row, Trooper Davis sits straight-backed, his eyes locked on Thorne, jaw set. He remembers the feel of the bodycam on his chest that day, the click of the cuffs, the sound of Miller’s boot tearing through paper.

“What you are here to do,” Thorne continues, “is not to pretend the page was never torn. Not to cover the smudge with white-out and act surprised when it shows through again.”

He looks out over the sea of faces, young men and women who chose to put on a uniform in a time when that choice draws more scrutiny than applause in many corners of America.

“Honor,” he says, “is not the uniform you wear. It’s not the badge on your chest or the gun on your hip. Those are tools. Symbols. But they are not you.”

He leans slightly forward, voice dropping, drawing them closer.

“Honor is the choice you make when no one is watching—and when everyone is. It’s choosing respect over suspicion when you approach someone on a bench. It’s choosing to listen before you shout. It’s choosing to see a human being where someone else only sees a threat.”

He doesn’t say “Black.” He doesn’t need to. The cadets understand exactly what he’s talking about.

“It is choosing justice over prejudice, every single day you put on this uniform,” he says. “And when you fail—and you will fail, because you are human—it is choosing to own it, fix it, and learn from it instead of burying it and calling the complaint unfounded.”

He straightens.

“Today, you begin a career in law enforcement in the United States of America,” he says. “In a time when the country is watching you more closely than ever. Some people out there will doubt you before they know you. Some will test you. Some will record you.”

A few chuckles ripple through the room, nervous but real.

“Good,” Thorne says. “Let them. Conduct yourselves in a way that can stand the light. Assume every interaction you have is being livestreamed straight into a living room in another state. Let that guide your choices. Not fear of exposure, but commitment to transparency.”

He looks again at the drawing.

“I keep this blue jay in my office,” he says. “Not because it’s my best work. It isn’t. Not because of what happened to it—though I won’t forget that, either. I keep it because it reminds me what can happen when power goes unchecked. How quickly a quiet afternoon in Central Park, in the middle of the greatest city in America, can turn into something else.”

He turns back to them.

“You are going to walk into communities from Brooklyn to Buffalo wearing that badge,” he says. “You will carry with you not just the authority of the state, but the legacy of everyone who wore a badge before you. The good and the bad. You don’t get to choose that legacy. You do get to decide what you add to it.”

He lets his gaze travel slowly from face to face, making brief eye contact with as many as he can. They shift under his stare, not from discomfort, but from the feeling of being seen.

“Do not fail,” he says finally.

The words are simple, but coming from him, they are more than closing remarks. They are orders.

The cadets rise as one, applause cracking like a series of small explosions in the room. Some of them look fired up, eyes bright. Some look solemn. Davis looks like someone who has carried a weight for a long time and is finally allowed to put it down somewhere useful.

Later that week, when the ceremony photographs fade from the trending bar on social media and the news cycle lurches on to the next crisis in another state, Central Park remains.

On another quiet afternoon, in a corner of the north end, a man sits on the same bench where everything started.

He wears a plain gray hoodie. Worn track pants. The weather has turned crisp again, the leaves around him a riot of orange and red against the Manhattan skyline. Joggers pass. A cyclist rings a bell. A cluster of tourists pose in front of the lake with the towers of Central Park West rising behind them, trying to fit New York into their phone screens.

On the bench, General James Thorne holds a sketchbook on his knee.

On the open page, beneath his steady hand, a new bird begins to take shape. Not a blue jay this time. A robin, plumper, perched on the edge of a puddle, its reflection just beginning to appear in the faint lines of pencil.

The charcoal moves in small, sure strokes. His hands, still strong despite the faint white scars where the cuffs bit months ago, are steady.

He hears footsteps approach and tense muscles he hadn’t noticed clench.

“Afternoon, sir,” a voice says.

He looks up.

A state trooper stands a few steps away on the path, campaign hat tucked under one arm, tan uniform neat, badge polished. Trooper Davis gives a small nod, his mouth tugging into a tentative smile.

“Didn’t mean to interrupt,” Davis says. “Just… saw you. Wanted to say hi. See how the new drawing’s coming along.”

Thorne’s shoulders ease.

“It’s coming,” he says. “Slowly. But that’s all right. Some things are worth taking your time with.”

He glances past Davis at the park, at the people moving freely through it, at the NYPD officers visible in the distance by a playground, chatting with parents, their hands nowhere near their weapons.

The system isn’t fixed. Not by a long shot. One task force, one commission, one training class cannot undo decades of damage or centuries of mistrust. There will be more incidents. More footage. More headlines.

But a battle has been won.

A line has been drawn.

A new standard has been set in at least one corner of the United States, in a state whose choices tend to ripple outward to others.

Thorne lowers his eyes to the page and draws another line, another feather, another curve of a wing.

In this quiet slice of New York City, a man can sit on a bench and sketch a bird again.

His wife’s memory sits beside him, as solid as the book on his knee, held safe not by law or policy alone, but by the determination of people who decided that “trash” was not what they wanted their uniforms to stand for.

Above the trees, the American flag catches the breeze, snapping once in the bright air.

He smiles, just a little, and keeps drawing.

News

MY DAD’S PHONE LIT UP WITH A GROUP CHAT CALLED ‘REAL FAMILY.’ I OPENED IT-$750K WAS BEING DIVIDED BETWEEN MY BROTHERS, AND DAD’S LAST MESSAGE WAS: ‘DON’T MENTION IT TO BETHANY. SHE’LL JUST CREATE DRAMA.’ SO THAT’S WHAT I DID.

A Tuesday morning in Portland can look harmless—gray sky, wet pavement, the kind of drizzle that makes the whole city…

HR CALLED ME IN: “WE KNOW YOU’VE BEEN WORKING TWO JOBS. YOU’RE TERMINATED EFFECTIVE IMMEDIATELY.” I DIDN’T ARGUE. I JUST SMILED AND SAID, “YOU’RE RIGHT. I SHOULD FOCUS ON ONE.” THEY HAD NO IDEA MY “SECOND JOB” WAS. 72 HOURS LATER…

The first thing I noticed was the silence. Not the normal hush of a corporate morning—the kind you can fill…

I FLEW THOUSANDS OF MILES TO SURPRISE MY HUSBAND WITH THE NEWS THAT I WAS PREGNANT ONLY TO FIND HIM IN BED WITH HIS MISTRESS. HE PULLED HER BEHIND HIM, EYES WARY. “DON’T BLAME HER, IT’S MY FAULT,” HE SAID I FROZE FOR A MOMENT… THEN QUIETLY LAUGHED. BECAUSE… THE REAL ENDING BELONGS TΟ ΜΕ…

I crossed three time zones with an ultrasound printout tucked inside my passport, my fingers rubbing the edge of the…

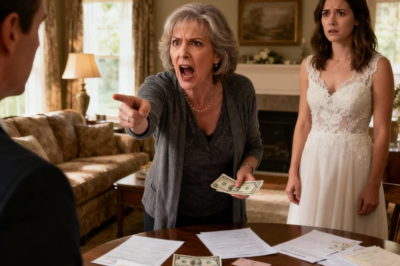

“Hand Over the $40,000 to Your Sister — Or the Wedding’s Canceled!” My mom exploded at me during

The sting on my cheek wasn’t the worst part. It was the sound—one sharp crack that cut through laughter and…

HOMELESS AT 45 AFTER THE DIVORCE, I SLEPT IN MY CAR. A STRANGER KNOCKED. “I’LL PAY $100 IF YOU DRIVE ME TO THE HOSPITAL.” DESPERATE, I AGREED. HALFWAY THERE, HE COLLAPSED. “MY BRIEFCASE… OPEN IT.” INSIDE WAS A CONTRACT. “SIGN IT. YOU’RE NOW HEIR TO $138 MILLION…” I READ THE FIRST LINE. MY HANDS SHOOK. “WAIT-WHO ARE YOU?” HIS ANSWER MADE MY HEART STOP

The cold vinyl of the steering wheel bit into Troy Waller’s forehead like a warning. He stayed there anyway, eyes…

FOR 11 YEARS, I ROUTED EVERY FLIGHT IN YOUR FATHER’S AIRLINE NETWORK. NOW YOU’RE FIRING ME BECAUSE YOUR FIANCÉE “DOES OPS NOW”?” I ASKED THE OWNER’S SON. “EFFECTIVE IMMEDIATELY,” НЕ SNAPPED. I HANDED HIM MY BADGE. “YOU HAVE 20 MINUTES BEFORE THE FIRST PLANES ARE GROUNDED. TELL YOUR DAD I SAID GOOD LUCK.

At 4:00 a.m. in Queens, the heartbeat of a midsize American airline sounds like a server fan grinding itself into…

End of content

No more pages to load