The mop moved like a metronome through the fluorescent glare of the fourth–floor corridor at St. Michael’s Medical Center in Chicago, long before the first code of the morning broke loose.

The night shift was ending, the day shift not quite awake yet. Machines hummed behind closed doors, monitors blinked in dim rooms, and somewhere down the hall a television murmured the early news over the distant rhythm of the city waking up along Lake Michigan.

Grace Miller worked in silence.

She pushed the mop in steady arcs, the bucket wheels squeaking softly on the waxed floor, the smell of disinfectant rising around her like a pale, invisible fog. Her light–blue housekeeping uniform hung a little loose on her narrow shoulders, the fabric faded in places from too many washes. A plastic ID badge bumped gently against her chest with each step.

MILLER, GRACE

ENVIRONMENTAL SERVICES

At fifty–two, she moved with the patient, unhurried precision of someone who had known hospitals her entire life on both sides of the bed. Her brown skin glowed soft under the harsh lights, and her dark eyes, framed by fine lines that told stories of laughter and grief, took in more than dust and footprints.

To most people rushing past nurses with charts, doctors with pagers, family members carrying coffee cups like lifelines she was just another cleaner. Background. Necessary, but forgettable.

Anyone who watched her long enough would know better.

There was a deliberate care in the way she wiped down the railings, lingering for a second where hands had gripped in fear. A quiet reverence in how she quietly straightened a magazine left half–open on a chair outside the ICU, or picked up a fallen teddy bear and placed it back by the edge of a crib.

She cleaned like someone who understood that every inch of this place was either a landing pad for hope or a trap for despair.

When a nurse in navy scrubs pushed through the double doors and nearly collided with her bucket, Grace stepped aside with the faintest of smiles.

“Morning,” the nurse muttered, eyes on the tablet in her hand.

“Good morning,” Grace replied softly.

The nurse was already gone.

Grace went back to work.

Hours earlier, when the sky over Chicago was still more gray than blue and the first train of the morning rattled toward downtown, Grace had been kneeling beside a narrow bed in a second–floor walk–up on the city’s south side. The apartment was small, the paint cracked in places, the pipes noisy in winter, but the rent was almost manageable and the radiator most days worked.

Her knees sank into the worn patch of carpet beside the bed.

“Lord,” she whispered, fingers loosely intertwined, eyes half–closed. “You know who’s coming through those doors today. The ones who are scared. The ones who don’t know they should be. The ones who think they’ve seen everything.”

She pictured faces she might never learn the names of. Then the ones she already knew by heart the security guard who worked double shifts to put his daughter through college, the nurse in pediatrics whose husband had left last Christmas, the night pharmacist with tired eyes and a gentle voice.

“And the doctors,” she added quietly. “Especially them. Give them wisdom where their books run out. Give them softness where they’ve grown hard. Steady their hands. Bend their knees, even if only in spirit.”

She rose, joints protesting a little, and smoothed the blanket on the bed. On the small table beside it lay a worn Bible with a cracked spine, a stack of bills folded inside as makeshift bookmarks, and a handwritten grocery list.

By the time she stepped out into the chill of pre–dawn Chicago, the prayer still wrapped around her like an invisible shawl.

At the other end of St. Michael’s, twelve floors above the street, Dr. Nathan Cole stood in front of his office window, staring out at the city.

The sun hadn’t fully risen, but the lights of downtown Chicago still burned against the fading dark towers of glass and steel, traffic already moving along the expressway, a smear of red taillights tracing the curve of Lake Shore Drive. Far off, the faint, familiar outline of the Willis Tower cut into the sky.

Nathan’s office was as immaculate as the rest of his public life.

Diplomas lined the wall behind his desk Harvard Medical School, Johns Hopkins residency, fellowships, awards. Articles from medical journals his articles were framed alongside. Everything was straight, aligned, ordered: a quiet gallery of achievements.

The man in the glass knew what they meant.

At forty–five, Dr. Nathan Alexander Cole was considered one of the best cardiovascular surgeons in the United States. Patients flew to Chicago to go under his knife. Hospital administrators bragged if his name appeared on their staff list. Medical students whispered about him in crowded lecture halls.

He was a star in a world where stars were made of statistics and survival rates, not movie scripts.

His white coat was impeccable, his posture as straight as the frames on his wall, his expression controlled: sharp blue eyes, dark blond hair just starting to show a few strands of gray at the temples, jaw clean–shaven.

Everything about him suggested precision.

Everything except the glass of whiskey on his desk ignored now, but not untouched from the night before.

He glanced at the clock. 6:15 a.m.

He picked up the chart in his hand again, eyes scanning lines of print and numbers. He had it almost memorized by now.

ETHAN MICHAEL MILLER

Age: 17

Admitted: 02:14 a.m.

Chief complaint: recurrent episodes of syncope, severe hypertension, arrhythmia.

The echo results were on the desk behind him. The lab values. The CT. None of them quite lined up. Too many odd spikes and dips, too little clarity.

Impossible case, one of the ICU residents had whispered.

Nathan didn’t believe in impossible cases. He believed in incomplete information.

He dropped the chart onto the desk, felt the familiar ache in his shoulders, the exhausted buzz at the base of his skull.

He’d been at St. Michael’s for almost fifteen years. In that time he had learned to read hearts like maps to track clots and ruptures and blockages with a kind of cold, elegant focus that had nothing to do with hope and everything to do with technique and timing.

Hope, he’d learned early, was a dangerous drug in a hospital.

It blurred lines. It slowed decisions. It made people whisper things like miracle and meant to be at the worst possible moments.

His father had taught him that lesson without meaning to.

Professor Alan Cole had been a brilliant man, a university lecturer who could talk for hours about philosophy and ethics and the fragile, flawed architecture of human belief. He’d also been one of the unluckiest patients Nathan had ever seen.

He’d fallen ill when Nathan was seventeen strange episodes of sky–high blood pressure, headaches that made him grip his temples and gasp, pounding heartbeats that seemed to shake his whole body. The Chicago hospital they’d taken him to had been full of confident men in white coats who ordered test after test.

For months, no one knew what was wrong.

Nathan remembered the nights in that hospital the smell of disinfectant, the taste of vending–machine coffee, his mother’s quiet voice praying in the corner of the room while monitors beeped in uneven rhythms. He remembered his father’s smile getting thinner, his skin getting sallow, his words slower.

When the doctors finally realized it was a rare adrenal tumor a pheochromocytoma too much time had passed. Things spiraled. Blood pressure sky–rocketed. There was talk of surgery, then complications.

His father died before they could do anything.

Nathan learned two things that year: that even the best doctors could miss what was right in front of them… and that God, if He existed at all, had terrible timing.

His mother, Rose Cole, had been a nurse for thirty years. She had stayed on her knees long after her husband’s funeral. She kept her faith like she kept their small house tidy, stubbornly intact.

“Son,” she used to tell him, sometimes standing in the kitchen with her hands still smelling faintly of latex and antiseptic, “before every procedure, remember to bend your knees. When science reaches its limit, faith keeps walking.”

He’d believed her for a while. Even in medical school, he sometimes ducked into empty chapels, muttered quick prayers over cadavers before exams, nodded to something invisible above the operating table.

Until seven years ago.

Rose’s stroke came out of nowhere.

One moment she was telling him a story about a patient from her old ward over Sunday lunch in his downtown apartment; the next, her words slurred and her face sagged on one side.

By the time the paramedics rolled her through St. Michael’s emergency doors, Nathan had already run through every protocol in his head. CT. Thrombolytics. Windows of time. Possibilities.

The film came back. Massive bleed. Wrong kind. Wrong place.

His training told him the truth his heart refused to hear.

There was nothing they could fix.

She died with her hand in his, monitors flatlining, the hospital pastor murmuring a Psalm at the bedside. Nathan stood there, exhausted and numb, listening to words about shepherds and valleys and fear no evil and felt absolutely nothing.

That night, he went home, emptied his mother’s small box of devotional cards into the trash, poured himself a drink, and made a quiet vow.

No more chapels.

No more whispered bargains with a God who did nothing when it mattered.

From then on, medicine was numbers and steel and skill. Nothing else.

Science became his only sanctuary.

That morning, though, looking at Ethan Miller’s chart, Nathan felt something he didn’t like.

Uncertainty.

He pinched the bridge of his nose, forced his thoughts into neat lines.

He would find the answer. He always did.

Down on the fourth floor, the intercom crackled, announcing the beginning of visiting hours. Footsteps grew louder. Voices layered over one another nurses giving shift reports, family members stumbling out of elevators, the squeak of those blue plastic visitor chairs being pulled up to bedsides.

Grace finished one corridor and moved to the next. She had been up since four a.m., but her body had long ago adjusted to the strange hours of hospital life. She paused in front of a door with a small sign that read:

ICU – AUTHORIZED PERSONNEL ONLY

Through the small glass window, she could see a glimpse of the unit beds barely visible behind screens, nurses moving like choreographed shadows in and out of rooms, monitors flickering.

She closed her eyes for a second.

“For them,” she whispered, the prayer automatic now. “For the ones fighting. For the ones who don’t know yet they’re losing. And for the ones making decisions.”

She pressed her hand lightly to the door. Then she gathered her mop and bucket and walked on.

Hours later, as the hospital settled into mid–morning chaos, Nathan walked briskly down that same fourth–floor corridor, a stack of test results in one hand.

He had slept maybe two hours in the on–call room, dreams fractured by the memory of his father’s monitors screaming and his mother’s broken whisper, It’s all right, baby, let go.

He’d spent most of the night reading, cross–checking, ruling out. Ethan’s episodes of fainting. The wild swings in blood pressure. The bouts of sweating and pounding heartbeats. The arrhythmias that made the ICU team hold their breath.

The usual suspects cardiomyopathy, structural defects, infections didn’t quite fit. The kid’s scans were clean. His labs were… odd, but inconclusive.

“Dr. Cole, his pressure spiked again around 4 a.m.,” the ICU resident had said. “We had to increase the beta–blocker. His mother ”

“I read the note,” Nathan had cut in.

He had seen the mother briefly a woman in her forties with tired eyes and a sweatshirt that had seen better days. She stayed planted by her son’s bed like a tree.

“It’ll be okay, Mom,” Ethan had told her, voice thin but steady. “I’m in good hands, right? And if it doesn’t work out here…” He’d glanced upward, a faint, crooked smile on his lips. “It’ll be fine up there.”

Nathan remembered the prickle of irritation that had swept through him.

Up there.

He hated when patients talked like that. When they pulled faith into the equation like a backup plan, as if the universe owed them a soft landing either way. To him, combining prayer and medicine wasn’t comforting; it was dangerous. It made people sign out against medical advice, chase miracle cures in online forums, refuse procedures days before something might rupture or fail.

He’d seen too many “God will heal me” stories end in code blues.

He preferred charts and scans to verses and platitudes.

He hit the corner of the corridor at speed, his mind already replaying Ethan’s symptoms.

He didn’t see Grace until he walked right into her.

The collision was small but sharp. His shoulder clipped the edge of her mop handle, and the impact knocked the folder in his hand. Papers slid out, skidding across the polished floor.

“Sorry,” he muttered, already bending down to grab the lab results before a stray heel smudged them. He didn’t look up.

“No problem, doctor,” came a calm voice above him.

Something about the tone steady, unruffled, like no one had spoken to him in exactly that way in a long time made him glance up.

Their eyes met.

She wasn’t young. The lines around her eyes deepened when she smiled the slightest bit, but there was no apology in her gaze. No flustered scramble like most people who got in his way.

He caught a flash of her badge.

MILLER, GRACE.

ENVIRONMENTAL SERVICES.

He straightened, irritated without fully understanding why.

Here he was, carrying the weight of a seventeen–year–old kid’s heart on his shoulders, and this woman was… sweeping.

Calmly.

“Any medical advice for me today, Mrs. Miller?” he said.

It came out harsher than he intended, edged with mockery. He heard himself anyway and winced internally. It was a line he’d thrown at support staff once or twice on bad days, a way to release pressure without cracking where it mattered.

Her gaze didn’t flinch.

She studied his face for a moment really studied it as if she could see past the polished coat and the taut jaw to the exhaustion pooled underneath.

“If you are taking care of the boy in bed seven,” she said quietly, “you might want to consider pheochromocytoma.”

Nathan blinked.

“What?” he said, the word more reflex than question.

“Pheochromocytoma,” she repeated, each syllable clear. “A tumor on the adrenal gland. It can release catecholamines in sudden bursts.”

She spoke like someone reciting from a textbook, or a lecture she’d given a long time ago.

“Block what causes the crisis first,” she added, “not just the symptom.”

He stared at her, the corridor noises fading a little.

Those symptoms. The unexplained spikes. The arrhythmias. The episodes of collapse.

His mind flashed through his father’s chart, his father’s months in a hospital bed, the late diagnosis.

How did she even know who was in bed seven?

“Where did you learn that?” he snapped, defensiveness pricking at his skin. “On the internet?”

“In life, doctor,” she replied, her tone unchanged. “And before you ask yes. I used to be a physician.”

He felt his stomach drop an inch.

“I lost my license a few years ago after a mistake,” she continued, matter–of–fact. “Today I clean corridors… and pray for the people who walk them.”

For a heartbeat, neither of them moved.

This woman, in a faded uniform with a mop at her side, had just dropped a diagnosis he hadn’t allowed himself to fully look at.

And it made sense.

Too much sense.

He felt heat rise up his neck part humiliation, part anger at himself, part… something else he refused to name.

“What happened?” The question came out before he could stop it, curiosity momentarily outrunning pride.

Grace’s gaze drifted over his shoulder, to some point down the hall where years of memory lived.

“A fourteen–year–old girl,” she said slowly. “Severe allergic reaction. The emergency cart wasn’t where it was supposed to be. By the time we found what we needed…” She paused. The silence filled in the rest. “…it was too late.”

Her face didn’t crumple. Her voice didn’t crack. But her eyes, for a moment, carried a weight he recognized.

“Someone had to take responsibility,” she went on. “I was the attending. It was my patient. My call. The board and I agreed.”

The board. The state medical board. The faceless “they” who could dismantle a career with a letter.

Nathan shifted, suddenly uncomfortable in his own skin.

He muttered something that might have been, “I’ll… look into it,” and stepped around her.

“Dr. Cole,” she said softly behind him.

He stopped.

“Steady hands also need bent knees,” she said. “Especially with a case like his.”

For the second time in five minutes, he felt like he’d been punched.

He walked away without answering, heart pounding against his ribs, his mind already counting off the tests he needed to order.

In the ICU, he went straight to the nurses’ station.

“Order plasma and urine metanephrines,” he told the resident. “Now. And get radiology ready for an adrenal CT. High suspicion of pheochromocytoma.”

The resident’s eyebrows shot up. “That’s… rare.”

“So is a seventeen–year–old with malignant hypertension and clean coronary arteries,” Nathan snapped. “Move.”

As the orders went out, he stepped into Ethan’s room.

The boy lay hooked up to monitors, the steady beeping of his heart rate filling the space. His mother sat in the chair by the bed, fingers wrapped around her son’s wrist, thumb tracing slow circles on his skin.

“Dr. Cole?” she asked, standing halfway as he entered.

“Mrs. Miller,” he said, his gaze flicking just once from her to the chart in his hand. Miller. The name didn’t register beyond the generic. “We’re running more tests. I think we might have found what’s causing this.”

“Is it serious?” she whispered.

He hesitated.

“It can be,” he admitted. “But if I’m right, we have options.”

She nodded, eyes glistening. Ethan watched him with quiet curiosity.

“Will it hurt?” the boy asked.

“The tests?” Nathan shook his head. “No. The surgery… we’ll cross that bridge when we get there.”

“There’s always a bridge, isn’t there?” Ethan said, a flicker of humor cutting through the wires and numbers around him. “Either here or… wherever else.”

Nathan resisted the urge to sigh.

“Get some rest,” he said instead.

When he stepped out of the room, he headed straight for a computer. While the orders processed, he typed in a name: GRACE MILLER.

The system pulled up her file EMPLOYEE: ENVIRONMENTAL SERVICES. Hired: six months ago. No mention of an MD. No access to clinical notes.

He frowned. Opened a browser. Typed again: “Dr. Grace Miller Chicago board suspension.”

It took less than a minute.

There it was. A five–year–old article buried on the fifth page of a local news site. “Teen Dies After Allergic Reaction in ER: Family Files Complaint. Doctor Reprimanded.”

He scanned the paragraphs. The words “system failure” and “missing crash cart” appeared once. The phrase “lead physician” appeared four times.

He closed the window.

Labs came back faster than he expected. Elevated metanephrines. Very elevated. Enough to make his scalp prickle.

The CT that followed confirmed it: a sizable mass sitting on Ethan’s right adrenal gland, quietly secreting chaos into his bloodstream.

Relief and shame collided in Nathan’s chest.

The answer had been there, just beyond his blind spot. It had taken a woman with a mop to yank his attention toward it.

Over the next few days, the pieces of Ethan’s treatment fell into place.

They started the right medications alpha blockers first, like Grace had said, then beta blockers softening the tumor’s ability to hijack Ethan’s system. The wild swings in blood pressure smoothed out. The arrhythmias eased. The boy’s color improved.

While he stabilized Ethan for surgery, Nathan found himself watching the fourth–floor corridor more than usual.

Grace moved through it like a quiet current. She emptied trash cans, wiped down surfaces, straightened blankets. She spoke gently to the older man who seemed to have no visitors, squeezed the hand of a woman crying outside a room, lent an ear to a nurse venting near the vending machines.

Once, Nathan saw her slip a small white card onto a bedside table where an elderly woman lay staring at the ceiling, silent tears leaking into her hair. Later, when the old woman’s granddaughter picked up the card, he caught a glimpse of neat handwriting:

You are not alone Grace

On the back, in smaller letters, a verse reference. He didn’t look it up.

On the eve of Ethan’s surgery, as the city outside turned orange with the last rays of a late–fall sun, Nathan walked past the hospital chapel.

He usually avoided it.

The small alcove off the main lobby always smelled faintly of candles and old wood, with a stained–glass window of a shepherd hung above five worn pews. Families ducked in and out, whispering hopes into the air. Patients in gowns sometimes shuffled in, pushing IV poles, looking small and scared.

He had walked past it a thousand times since his mother’s funeral without stepping through the doorway.

This time, he saw someone inside.

Grace.

She was alone, kneeling on the cushioned rail, head bowed, hands loosely clasped. The light from the stained glass painted her face in shades of red and blue.

He stood at the threshold, feeling like an intruder in his own hospital.

He almost turned away.

“May I join you?” he heard himself ask.

His voice sounded different in the quiet, oddly gentle.

Grace turned, surprise flickering into a small smile.

“Of course, doctor,” she said. “This house belongs to everyone.”

House. Not room. Not space. House.

He stepped inside.

The silence felt heavy, but not oppressive. He sat on the end of the first pew, back straight, hands flat on his knees, like he was at some strange, sacred job interview.

He stared at the cross on the wall instead of at her.

“Why didn’t you try to get your license back?” he asked finally, eyes still fixed ahead.

There was a long pause.

“Some losses bring lessons you can’t learn from books,” she said. “I lost the right to practice medicine. I didn’t lose the calling to care for people.”

He turned his head to look at her.

“You could be doing more than cleaning floors,” he said. It came out more frustrated than he intended.

She smiled not offended, not bitter. Just… amused, almost.

“Who says I’m not doing much?” she asked, lifting one eyebrow. “I know every corner of this hospital. I see people when they think no one is looking. Sometimes a kind word, or a prayer whispered when they’re not aware, moves more in a person than a prescription.”

He thought of his mother again, of the way she used to sit on bedsides and listen even when she was off the clock.

“I used to pray,” he said quietly, surprising himself. “Before every big surgery. Before exams. Then… I stopped.”

“I figured,” she said softly.

“Because of your mother,” she added, like she already knew, though he hadn’t told her.

He stiffened.

“How ”

“Your name is respected in this city,” she said. “People talk. Nurses who worked with her talk. They say Rose Cole could start an IV on a whisper and comfort three families at once with the same smile.”

He swallowed, throat tight.

“She taught you that phrase, didn’t she?” Grace asked. “About steady hands and bent knees.”

He nodded once.

“She was wrong,” he said impulsively. “About the bent knees part, at least.”

Grace didn’t argue. She just looked at him with eyes that had seen enough to know grief when it bluffed.

“Tomorrow is the boy’s surgery,” he said, needing to change the subject, if only to step away from the old ache. “If the tumor is handled incorrectly, it can dump so many hormones into his system that his heart… won’t handle it.”

“I know,” she said. “I’ve assisted in those surgeries before. They’re not forgiving.”

He raised an eyebrow.

“Before,” she added. “In… another life.”

There was something in her voice that made his chest tighten. Regret and acceptance, braided together.

“I’ll be praying for him,” she said. “And for you.”

“You don’t have to ” he started.

“I know,” she cut in gently. “But I will anyway.”

He didn’t know what to say to that.

The next morning, the air in the OR felt colder than usual.

The bright lights overhead turned the surgical field into a small, blinding planet floating in a universe of shadows. Machines beeped in patient, unrelenting rhythms. Ethan lay on the table, his chest rising and falling under the ventilator’s guidance.

The anesthesiologist called out numbers. The scrub nurse passed instruments. The rest of the team stood ready, poised at the edge of crisis.

Nathan took his position, gloved hands hovering.

“Let’s get started,” he said.

They hadn’t made it far when it happened.

Ethan’s blood pressure, already tricky, suddenly spiked. The numbers on the monitor jumped. Alarms erupted in sharp staccato.

“Two-twenty over one-forty,” the anesthesiologist barked. “Heart rate one–fifty and climbing.”

Nathan’s pulse matched it for a second.

This was their worst fear.

In those first few heartbeats, the OR dissolved. The present blurred into the past.

He saw his father thrashing weakly on a bed, monitors screaming, doctors the same kind of doctors he had now become shouting orders and flipping through protocols. He smelled the stale coffee and the antiseptic. He heard his mother’s soft crying in a corner as someone put a hand on her shoulder and said, We’re doing everything we can.

He felt the helplessness of seventeen again, raw and hot in his throat.

Panic nudged the edges of his composure.

Then, through the noise, through the swirl of terror and memory, a quiet sentence rose up from some deep, buried place.

Steady hands also need bent knees.

Grace’s voice. His mother’s voice. Layered.

He drew in a breath.

“Increase the alpha blocker,” he said sharply. “Do it gradually. No sudden moves. Talk to me with every change.”

“Done,” the anesthesiologist said. “Drip going up.”

He closed his eyes for half a second.

And in a move that made the scrub nurse glance up in startled confusion, Nathan lowered his head.

He didn’t drop to the floor. His knees didn’t hit tile. But something inside him bent.

Lord, he thought, the word startling in his own mind. If You’re there… help me not kill this boy.

It wasn’t poetic. It wasn’t polished. It was desperate and small and honest.

He opened his eyes.

The panic had loosened its grip. Not gone. But manageable.

He watched the numbers with the same focus he used to watch game scores as a kid.

“Pressure’s coming down,” the anesthesiologist said. “One–eighty… one–sixty… one–forty–five…”

“Good,” Nathan said. “We proceed when he’s stable. We take the tumor slow. We don’t provoke it.”

Hours thinned and thickened around them.

He moved with the precision he was known for, but there was something else braided into it now a quiet awareness that his hands were not the only factor in this room, whether he liked that reality or not.

Three hours later, the tumor sat in a metal bowl on the side table, a small, pale mass that had wreaked havoc far larger than its size.

Ethan’s vitals had held steady through the removal.

“Good work, team,” Nathan said, the words heavy with more than just professional satisfaction.

When he stripped off his gloves, his fingers trembled.

Not from exhaustion.

From the slow, dawning sense that something inside him had shifted in those few seconds of silent prayer.

He stepped out of the OR and into the hallway, the sudden ordinary noise of the hospital jarring after the contained world of the operating room.

Grace was there.

She was wiping down a large window near the waiting room, cloth moving in slow circles, the city skyline reflected faintly in the glass.

Their eyes met.

He didn’t smile, not exactly. But he nodded.

Her lips curved, a small light breaking through the calm.

“How is he?” she asked.

“He made it,” Nathan said. “Tumor’s out. No complications.”

She closed her eyes briefly, a silent thank–you directed somewhere he’d only just dared to look toward again.

In the days that followed, Ethan recovered faster than anyone had predicted.

Within a week, his monitors were gone, his color had returned, and the wild spikes that had haunted his nights had disappeared. The nurses joked that he walked more laps around the ward than some of the orthopedic patients.

Nathan did his rounds, checked incisions, ordered follow–up labs. But his mind kept circling something else.

Miller.

He saw the name on Ethan’s chart every morning. Saw it on Grace’s badge every day in the corridor.

Miller wasn’t an uncommon last name. But the way she’d spoken about the boy in bed seven. The way she’d known.

One morning, he stopped at the foot of Ethan’s bed and glanced at the chart again.

ETHAN MICHAEL MILLER

Mother: SARAH MILLER

Emergency contact: GRACE MILLER – GRANDMOTHER? OTHER?

The second contact line had been left blank, hastily filled in the night Ethan arrived. The handwriting was messy. The relationship line was smudged, unreadable.

Later that day, Nathan found Grace in the staff cafeteria, sitting alone with a Styrofoam cup of tea cradled between her hands. Through the wide windows, the Chicago afternoon glowed cold and bright, the parking lot dotted with cars and the distant line of the L tracks.

He sat down across from her without asking permission.

“He’s your son,” he said.

It wasn’t a question.

Grace looked at him over the rim of her cup. There was no point pretending with a man who cut through flesh and bone every day for a living.

“Yes,” she said. “Ethan is my son.”

Something settled into place in his mind, like a puzzle piece finally sliding into the right slot.

“Why didn’t you tell me?” he asked.

“Because you needed to see a patient,” she said simply, “not a janitor’s kid. And because I didn’t want anyone to think I was trying to… influence your decisions.”

Her eyes dropped for a moment, to the table, where small scratches marked years of hurried meals.

“I already have a history in this hospital,” she added, voice quiet. “A complicated one.”

“You thought it would bias me,” he said.

“I thought it could hurt him,” she corrected.

He absorbed that.

“Is that why you took the job here?” he asked. “Environmental services. After everything?”

“Not exactly,” she said. “I took the job because our family insurance changed. My husband’s company downsized. The new plan gave better coverage if I worked at an affiliated hospital.”

She gave a small shrug.

“I knew Ethan’s episodes were getting worse. I also knew, from experience, that sometimes doctors don’t see what’s in front of them until it’s almost too late. I wanted to be…” She searched for the word. “…near. Just in case.”

“How long have you known?” he asked. “About his condition.”

“Known?” she echoed. “I didn’t know. But I suspected. Patterns repeat themselves, Dr. Cole. The headaches. The sweating. The fainting. I saw those symptoms in textbooks. I saw them in your father’s case ”

She stopped herself short, eyes widening slightly.

He stared.

“People talk,” she said quickly. “Nurses. Old case reviews. I’d heard…”

He exhaled.

“You were right,” he said. “About everything. The diagnosis. The approach. Even the… knees.”

Her mouth twitched.

“How did you know?” he pressed. “In that hallway. It can’t just be ‘patterns.’”

She looked down at her tea, watching the steam curl.

“I’ve treated patients with pheochromocytoma before,” she said. “I’ve missed it, too. I’ve seen what happens when we catch it too late. It’s one of those diagnoses that hides in plain sight.”

She hesitated.

“But it was more than that,” she admitted. “When I heard someone in the ICU had a case nobody could pin down, something inside me… stirred. Call it medical experience. Call it instinct. I call it God whispering something I couldn’t ignore.”

He didn’t trust his voice enough to answer right away.

Finally, he spoke.

“I’m going to talk to the state board,” he said.

She blinked.

“What?” she asked.

“Your case,” he said. “The one from five years ago. It needs to be reviewed. What happened to that fourteen–year–old girl wasn’t just on you, and we both know it.”

“Dr. Cole, there’s no ”

“Nathan,” he cut in. “My name is Nathan. And yes, there is a need. Not just for you. For the residents we’re training. For the patients who should have you at their bedside instead of just your prayers mopped into the floor.”

He leaned forward.

“I’ve seen enough morbidity and mortality reports to know when a hospital sacrifices a single name to save its own reputation,” he said. “You took the hit for a system that failed. That doesn’t sit right with me anymore.”

Her eyes glistened.

“You don’t owe me this,” she whispered.

He shook his head.

“This isn’t about what I owe you,” he said. “It’s about what we owe the truth. And maybe…” He swallowed hard, feeling the words catch on something softer than his pride. “…maybe it’s also about what I owe my mother. You’re the kind of doctor she wanted me to become. I’m only just starting to understand what that means.”

The weeks that followed were some of the busiest of his career and not because of surgeries.

He spent nights combing through old records incident reports, staffing logs, pharmacy audits. He tracked down nurses who had been on duty the night the fourteen–year–old girl, Jennifer Adams, had died. One had retired to Arizona. Another was working in a clinic in a neighboring suburb. He called them, traveled to see them on his rare days off, listened to stories that didn’t quite match the neat version in the board’s old report.

The crash cart that had gone missing because it had been moved for a surprise inspection. The intern who’d panicked and grabbed the wrong tray, then quietly resigned two weeks later. The nurse who had told a supervisor about understaffing issues and had her concerns buried.

The more he dug, the clearer the picture became.

Grace had been responsible that night. But she had not been the only one.

St. Michael’s administration, facing a grieving family and the threat of bad press, had needed a story that was simple. A single doctor’s error was easier to swallow than a hint of systemic rot.

Grace, wracked with guilt and raised to own her mistakes, had lowered her head and accepted the brunt of the blame.

Five months after Ethan’s surgery, a special meeting was convened.

The boardroom on the top floor was full: hospital administrators in dark suits, members of the medical board, the chief of staff, a lawyer or two. The windows looked out over the city, but the air inside felt tight.

Grace sat at one end of the long table, her hands folded neatly in her lap. Ethan sat beside her, hair grown back, cheeks full, eyes flicking between the adults in the room.

Nathan sat near the center, a stack of files in front of him.

“Thank you all for coming,” said Dr. Lawrence, the medical director, clearing his throat. “We’re here to review the case of Dr. Grace Miller and the events of April 2018.”

He spoke the words like reciting a biography. Regulations. Dates. The official version.

Nathan listened, then slid the first file forward.

“With all due respect, Dr. Lawrence,” he said when it was his turn, “the version we accepted five years ago left out critical information.”

He laid out what he’d found.

The missing crash cart. The intern’s medication mix–up. The nurse’s ignored warnings about understaffing. The timeline that showed Grace had been trying to save a girl without the tools she’d been promised would be available.

He quoted policy. Pointed to precedence in other cases. Showed how the system had narrowed its focus onto one person because it was easier than admitting bigger fault lines.

The room shifted.

Some faces softened. Others hardened.

At the far end of the table, Grace sat so still she might have been carved from stone. Ethan’s hand found hers and squeezed.

After two hours of questions and rebuttals, Dr. Lawrence sighed.

“After an extensive review,” he said finally, glancing at the board members, “the hospital and the state board recognize that Dr. Miller was not solely responsible for the loss of patient Jennifer Adams. Systemic failures and inadequate supervision contributed significantly to the outcome.”

Silence.

“Accordingly,” he continued, “we offer our formal apology for the way responsibility was apportioned. And we propose not only the reinstatement of your medical license, Dr. Miller, but also a position within our medical education department. Your experience can help us train more careful, more compassionate physicians.”

For a moment, all sound disappeared under the pounding of Grace’s heart in her ears.

Her vision blurred.

She lifted shaking hands to her mouth, trying to contain the sob that managed to escape anyway.

Ethan turned to her, a grin spreading across his face, tears shine bright in his eyes.

“You did it, Mom,” he whispered.

She shook her head, laughing through tears.

“No,” she whispered back. “We did.”

As they left the boardroom, blinking in the sudden brightness of the hallway, Nathan stood waiting.

She stopped in front of him, the lanyard with her reinstated license letter still warm in her hand.

“Thank you,” she said.

The words were small compared to what he’d done, but she hoped he heard the full weight of them.

“I should be the one thanking you,” he said. “You saved Ethan twice. Once with your mind, once with your faith. You also reminded me that medicine without both… is missing something vital.”

Her mouth curved.

“You know, Nathan,” she said, “sometimes God uses the most unlikely things to fix what’s broken. Like a mop and a bucket bringing a doctor back to an operating room.”

“And an arrogant joke in a hallway dragging a surgeon back into a chapel,” he replied.

They both laughed, the sound light in a way it hadn’t been in years.

Six months later, St. Michael’s Medical Center announced a new mandatory course for residents and staff.

HUMANIZED MEDICINE: SCIENCE, HUMILITY, AND THE ART OF CARE.

Instructor: Dr. Grace Miller.

On the first day, the lecture hall was fuller than anyone expected. Young doctors in short white coats. Seasoned physicians with arms crossed, skeptical but curious. Nurses on their own time, sitting along the back wall. Even a security guard or two lingering near the door.

Grace stood at the podium, not in a cleaner’s uniform this time, but in a white coat again. It looked different on her now not as armor, but as a garment she wore with full awareness of its weight.

She told them stories.

About Jennifer. About how you can do everything in your power and still lose, and how you carry that loss. About Ethan, and how sometimes the person who sees what everyone else misses isn’t the one with the longest title.

She talked about protocols and checklists and double–checks on crash carts. About how systems save lives when they’re respected. About how egos kill when they go unchecked.

She talked about kneeling.

Not as ritual. Not even as religious requirement.

As posture.

“You’ll hear a thousand times in your training that you need steady hands,” she told them. “That your confidence will help patients trust you. That your certainty will calm families.”

She paused, scanning the room.

“What they won’t tell you as often is that you also need bent knees,” she continued. “Literally, when you’re checking on a child so you’re not towering over them. Figuratively, when you admit you don’t know something and ask for help. Spiritually, if that’s part of your life, when you hit a wall and science has nothing new to say.”

In the second row, Dr. Nathan Cole sat with a notebook open on his lap, pen in hand.

He had nothing to prove by being there. His numbers spoke for themselves. But he took notes anyway.

Before every major surgery now, he did something he’d stopped doing for seven years.

He slipped into the chapel or, if time was too tight, closed his eyes in the scrub room. He bowed his head. Sometimes he knelt; sometimes he just let his heart do the bending.

He didn’t bargain. He didn’t demand.

He simply acknowledged that his hands steady as they were weren’t the only thing keeping a heart beating on a table.

The fourth–floor corridor changed too.

Families still paced. Nurses still hurried. Machines still hummed. But tucked between the official posters about hand hygiene and fall risk, a new framed picture hung on the wall.

It was simple.

A pair of gloved hands hovering over a chest. Below them, a pair of knees pressed to a tiled floor, drawn in soft, impressionistic lines. At the bottom, in neat script, a sentence:

Steady hands and bent knees save more lives than technique alone ever could.

Grace walked past it every morning on her way to the residents’ lounge, where she made a point of leaving a pot of fresh coffee and a bowl of fruit that somehow never emptied completely.

Sometimes she still picked up a stray wrapper in the hallway. Old habits didn’t just vanish. Sometimes she still paused outside the ICU doors, resting her palm on the cool metal, whispering a silent prayer for the ones inside.

She was a doctor again.

But she was also still the woman with the mop who knew every corner of the hospital.

On a gray Wednesday afternoon, months after her license had been reinstated, she saw Nathan standing at the window on the fourth floor, looking out at the city.

“Hard day?” she asked, joining him.

“Complicated case,” he said. “Teenage girl. Arrhythmia. Scared mother. I’ve seen this movie before.”

“And?” she prompted.

“And this time,” he said, a half–smile pulling at his mouth, “we caught it early. Because a resident remembered your lecture. Asked the right questions. Ordered the right tests.”

He exhaled.

“I went down to the chapel before that case,” he added. “Just for a minute.”

“How did it feel?” she asked.

He considered.

“Like I was finally doing the job my mother thought I was training for,” he said. “Not just fixing hearts. Guarding them.”

They stood there in comfortable silence, watching the Chicago traffic crawl along the wet streets below.

In a city of millions, in a hospital where lives began and ended every day, their story was just one thread in a vast tapestry.

A woman who lost everything she thought defined her and found a new way to heal with a mop in her hand. A surgeon who trusted only his own skill until a cleaning lady saw through his arrogance and handed him a forgotten diagnosis and a forgotten habit on a polished tray.

Science and faith still wrestled in those halls, in different rooms, in different bodies. Machines still failed. Prayers still went unanswered in ways that hurt.

But somewhere between the charts and the chapels, the protocols and the whispered pleas, a new kind of medicine had taken root at St. Michael’s.

Not perfect.

Not magic.

Just real.

Made up of steady hands, bent knees, and two people who had learned the hard way that sometimes the most important miracles aren’t the ones that stop death

but the ones that bring a heart, human and stubborn, back to life.

News

I was at TSA, shoes off, boarding pass in my hand. Then POLICE stepped in and said: “Ma’am-come with us.” They showed me a REPORT… and my stomach dropped. My GREEDY sister filed it so I’d miss my FLIGHT. Because today was the WILL reading-inheritance day. I stayed calm and said: “Pull the call log. Right now.” TODAY, HER LIE BACKFIRED.

A fluorescent hum lived in the ceiling like an insect that never slept. The kind of sound you don’t hear…

WHEN I WENT TO MY BEACH HOUSE, MY FURNITURE WAS CHANGED. MY SISTER SAID: ‘WE ARE STAYING HERE SO I CHANGED IT BECAUSE IT WAS DATED. I FORWARDED YOU THE $38K BILL.’ I COPIED THE SECURITY FOOTAGE FOR MY LAWYER. TWO WEEKS LATER, I MADE HER LIFE HELL…

The first thing I noticed wasn’t what was missing.It was the smell. My beach house had always smelled like salt…

MY DAD’S PHONE LIT UP WITH A GROUP CHAT CALLED ‘REAL FAMILY.’ I OPENED IT-$750K WAS BEING DIVIDED BETWEEN MY BROTHERS, AND DAD’S LAST MESSAGE WAS: ‘DON’T MENTION IT TO BETHANY. SHE’LL JUST CREATE DRAMA.’ SO THAT’S WHAT I DID.

A Tuesday morning in Portland can look harmless—gray sky, wet pavement, the kind of drizzle that makes the whole city…

HR CALLED ME IN: “WE KNOW YOU’VE BEEN WORKING TWO JOBS. YOU’RE TERMINATED EFFECTIVE IMMEDIATELY.” I DIDN’T ARGUE. I JUST SMILED AND SAID, “YOU’RE RIGHT. I SHOULD FOCUS ON ONE.” THEY HAD NO IDEA MY “SECOND JOB” WAS. 72 HOURS LATER…

The first thing I noticed was the silence. Not the normal hush of a corporate morning—the kind you can fill…

I FLEW THOUSANDS OF MILES TO SURPRISE MY HUSBAND WITH THE NEWS THAT I WAS PREGNANT ONLY TO FIND HIM IN BED WITH HIS MISTRESS. HE PULLED HER BEHIND HIM, EYES WARY. “DON’T BLAME HER, IT’S MY FAULT,” HE SAID I FROZE FOR A MOMENT… THEN QUIETLY LAUGHED. BECAUSE… THE REAL ENDING BELONGS TΟ ΜΕ…

I crossed three time zones with an ultrasound printout tucked inside my passport, my fingers rubbing the edge of the…

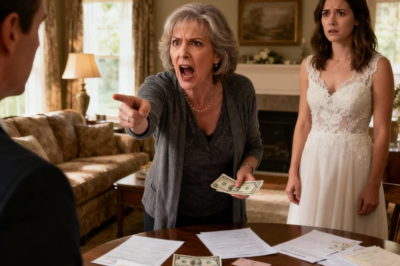

“Hand Over the $40,000 to Your Sister — Or the Wedding’s Canceled!” My mom exploded at me during

The sting on my cheek wasn’t the worst part. It was the sound—one sharp crack that cut through laughter and…

End of content

No more pages to load