By the time the sky over northern Colorado turned the color of a fading bruise, my whole life had already tilted—only I didn’t know it yet.

The mountains west of Fort Collins were just silhouettes against a gray October evening, their edges smudged by low clouds and the kind of wind that smells like snow still thinking about it. I turned off Harmony Road and into our subdivision, past manicured lawns and identical mailboxes, the kind of neighborhood real estate agents describe as “quiet, desirable, family-friendly.” The kind of neighborhood where bad things are supposed to happen to other people, in other states, on channels you can switch off.

My shoulders ached from ten hours of pretending I wasn’t drowning at the office. Some guy from Denver had spent half the afternoon yelling at me on speakerphone about numbers I hadn’t messed up. Traffic on I-25 had turned into a slow-moving parking lot. My jaw still hurt from clenching it.

All I wanted was a hot shower, a glass of cheap red wine, and my husband’s arms around me. Just one night where the world could pretend to be soft again.

Instead, Meredith’s white SUV was parked diagonally across our driveway like a barricade.

The porch light above our blue front door glowed warmly, like a photograph in a realtor’s brochure. Meredith’s license plate—custom, of course—winked at me in the fading light. My sister-in-law had never liked me. She wore that dislike like perfume: expensive, heavy, impossible to ignore. Five years of strained smiles at holidays. Five years of condescending comments about “smart girls who don’t know how to relax.” I had stopped trying to make her like me when I realized she enjoyed not liking me.

Seeing her car in my driveway at dusk, on a weeknight, put a splinter of unease straight through my chest.

I drove two houses down and parked at the curb, like I was a guest in my own life. The air bit at my cheeks when I stepped out, cold and thin with that high-plains edge. I grabbed the grocery bag with the bottle of Cabernet I’d promised myself and walked back up the street, past the neighbors’ lit windows and pumpkin decorations, toward the house I’d believed was mine in every way that mattered.

Our living room lamp glowed softly behind the curtains. The wreath on the door was one I’d picked out on sale at Target. The welcome mat still said THE THOMPSONS in loopy script.

For one ridiculous second, I thought: Maybe Meredith just dropped by with takeout. Maybe they’re planning some kind of surprise. Maybe today doesn’t have to be another day that hurts.

I pushed the key into the lock and eased the front door open just enough to slip inside.

The smell hit me first: cinnamon and vanilla. The scent of the candle Drew always teased me about, calling it “basic” in that joking way that never quite felt like a joke. It mingled with something else—Meredith’s perfume, sharp and floral and expensively smug.

Then I heard it. Her laugh. Low. Satisfied. The kind of laugh that says, I know something you don’t.

Voices floated down the hallway from the kitchen. I stood in the dark of our entryway, half in, half out, as if the threshold were a line across time.

“God, she has no idea,” Drew said.

His voice was relaxed. Lazy. Pleased in a way I hadn’t heard directed at me in months. The sound slid under my skin and lodged there like a sliver of ice.

Meredith chuckled. “Mia never has had much imagination.”

I froze. Every tired cell in my body went on alert.

“Tessa came over at lunch.” Drew’s voice dropped, conspiratorial. “Three times today, Mere. Three.”

My keys slid from my hand. They hit the tile with a bright, shattering clink that rang far too loudly in the quiet house.

No one heard it.

My husband and his sister were too busy dissecting my life in the kitchen of the house I paid for.

Meredith made some joke about stamina—I don’t remember the exact words. What I do remember is Drew’s laugh in response. That easy, delighted laugh he used to save for Sunday mornings when we’d sleep in, bodies tangled, nowhere to be but with each other.

He hadn’t laughed like that with me in a long time.

Then he said the sentence that turned all the blood in my veins to ice.

“Community property state, remember?” There was a scrape of chair legs on tile. “I file, I get half of everything. The trust, the investments, all of it. She built it. I cash it. Tessa’s already looking at houses in Arizona.”

The grocery bag handles cut into my fingers. The neck of the wine bottle dug into my palm. For a second, the world went out of focus, like someone had smeared Vaseline over the lens.

Community property. Half.

He sounded proud of himself. Like he’d cracked some code. Like he was talking about a lottery win instead of my parents’ legacy.

I stood there in the dark hallway of my Fort Collins home—my home—listening to the man I’d married turn me into a line item in his financial plan.

Three years of marriage. Three years of me working late so he could “find himself” after his startup imploded in Denver. Three years of nodding along while he talked about his next big idea, his future, his vision, while I quietly paid the mortgage and the utilities and the health insurance.

Three years of me telling myself that the distance between us was temporary. That the sex drying up was just stress. That his late nights were drinks with clients, not someone named Tessa.

I had suspected something was off. You don’t share a bed with someone for that long without feeling when they roll away from you in more ways than one. But suspicion is a fog. The words coming out of his mouth in that moment were brick.

I stepped backward, careful, like any noise might make the floor give way.

The house suddenly felt hostile, every familiar object rearranged around a new truth.

“Arizona?” Meredith drawled. “You sure you’re ready to trade snow for sun, little brother?”

Drew snorted. “Once the money hits, I’ll be ready for anything.”

The kind of laughter I would have once thought harmless—just family teasing—now sounded like teeth.

My hand found the doorknob behind me. I eased it open, the way you do when you’re trying not to wake a sleeping child. The cold air rushed in as I slipped back out into the dusk, pulling the door shut until the latch clicked.

I stood on the porch for a heartbeat, staring at the painted blue door I’d picked out the week we moved in, the one I’d been so proud of because it made the house “pop” on our street.

It was just a door.

I walked away.

The engine roared too loud in the quiet cul-de-sac when I started the car. I sat there in the driver’s seat, staring at the pretty brick house with the manicured shrubs and the fairy lights I’d strung around the porch last Christmas, and realized that whatever “home” had been, it wasn’t there anymore.

When I was twenty-five, my parents died in a plane crash over Texas. One minute they were on a flight for a conference; the next minute there was a headline and a blinking voicemail from an airline representative I never wanted to hear again.

People said I was lucky. Lucky the trust was ironclad. Lucky my parents had planned so well. Lucky I’d never have to worry about money in my life.

I never once felt lucky. I felt orphaned. Unmoored. Like someone had scooped out the middle of my life and poured cement into the empty space.

Drew showed up a year later at a charity gala in downtown Denver, all gentle hands and big promises. He listened. He asked about my work, my parents, the foundation named after them. He said things like, “You don’t have to be strong all the time, you know,” in a way that made me feel seen and cared for.

Being chosen by him felt like oxygen after a year of breathing through a straw.

I should have remembered that oxygen can be turned off.

Headlights streaked past on the boulevard at the end of our street. I blinked. The grocery bag was still in my lap, the bottle of Cabernet pressing into my ribs every time I inhaled.

I didn’t cry.

I backed out of the spot, turned away from the house, and drove.

Downtown Fort Collins glowed with warm lights and the polite bustle of a college town on a chilly evening. I barely registered the brick storefronts, the bars lined with CSU hoodies, the couples holding hands under twinkle lights. My hands shook on the steering wheel all the way to Sophia’s building.

Sophia buzzed me in on the first ring.

She opened the condo door in pajama shorts and a CSU sweatshirt, hair in a messy bun, eyes sharp. One look at my face and she reached out, grabbed my wrist, and pulled me inside without a word.

I dropped the grocery bag on her kitchen counter. The bottle rolled once, then settled.

The words came out in ragged pieces. The hallway. The cinnamon candle. Meredith’s laugh. Drew’s voice. Three times today. Arizona. Community property. She built it. I cash it.

I talked until the story was out and I felt scraped hollow, like I’d turned myself inside out and left every nerve exposed on her couch. Sophia listened like it was her only job. No interruptions. No “Are you sure you heard that right?” Just her hand on my knee, steady and warm.

When I finally ran out of sentences, the silence in her living room felt almost gentle.

Sophia stood, walked to her liquor cabinet, poured two fingers of bourbon into a glass, and slid it across the coffee table.

“Mia,” she said quietly, “what do you need?”

I stared at the glass. At my shaking hands. At the city lights blinking through her balcony doors.

What I needed was to turn back time. To un-hear. To un-know. To go home to a house that still belonged to me.

What I said, eventually, was, “I need what’s mine.”

What I didn’t say out loud was the second part: And I need to disappear before he takes it.

The bourbon burned all the way down. It felt like a promise.

I woke the next morning on Sophia’s couch with a mouth that tasted like ash and a headache that throbbed behind my eyes. For a moment I lay still, listening. No cinnamon candle. No murmur of Drew’s voice. No Meredith.

Just the hum of Sophia’s refrigerator and the faint whoosh of a car on the street below.

My phone buzzed somewhere in the blanket nest. I found it, blinked at the screen. Two texts from Drew.

Everything okay, babe? You never came home.

An hour later:

Mia? Seriously. Where are you?

Then a message from Meredith:

You seemed upset. Call me. We can clear this up.

Clear this up.

As if there were a version of events where that conversation in my kitchen was anything other than exactly what it sounded like.

I watched the screen go dark in my hand.

I didn’t feel angry. Not yet. Anger is hot, wild, consuming. What I felt was something else. A strange, metallic kind of calm, like the pressure drop before a storm when the air gets too heavy to breathe.

Sophia padded into the living room in slippers, her dark hair now twisted into something neater, a mug of coffee in her hand.

“You look like you made a decision in your sleep,” she said.

“I did,” I answered.

She raised an eyebrow. “Are we talking illegal or just extremely satisfying?”

“Legal.” I hesitated. “Mostly.”

She snorted. “That’s my girl.”

We sat at her kitchen island. She made coffee strong enough to peel paint. I opened my laptop. The familiarity of my banking login screen flickered up like an old, slightly unsympathetic friend.

The trust my parents left wasn’t simple. They’d built layers. Investments, brokerage accounts, a small annuity. A conservative portfolio from a lawyer who believed in stability more than risk. The house we lived in—my pretty brick Fort Collins house with the blue shutters and cinnamon candle—was, on paper, mine alone. I’d titled it that way because the trust lawyers had insisted. Drew had bristled about it once, saying he didn’t like feeling like a “guest” in his own home, but he’d gotten over it.

I had kept our finances mostly separate out of habit, not suspicion. A leftover reflex from a girl who’d watched her parents’ lives vanish in a headline and wanted to control the one thing she could.

That habit, it turned out, was going to save me.

By noon, I had transferred what I could from the trust’s more fluid accounts into subaccounts he didn’t know existed. Nothing illegal; no shell games. Just consolidating. Moving funds from “easy to see” to “harder to find.” Spreadsheets and routing numbers became my armor.

By three, I’d opened a brand-new account at a bank neither of us had ever used, routed through Sophia’s address. I clicked through online forms until my name filled every field and my parents’ trust sat behind new passwords and two-factor authentication.

By six, I’d canceled every joint credit card and transferred the remaining balance from our shared checking into my own new account. I did the math in my head, calculated what amount would send a clear message without looking like panic.

I left exactly $31,247 in the old account. Enough for him not to claim I’d left him destitute. Enough to cover his gym membership, his car payment, his drinks with “clients.” Enough to say: I didn’t wipe you out. I just stopped letting you spend my future.

I didn’t cry through any of it. My hands were steady over the keyboard. My thoughts felt crystalline, each step snapping into place like I’d rehearsed this escape a thousand times in dreams I didn’t remember.

Grief seemed like a luxury for another day.

That evening, my phone lit up with Drew’s name. I let it vibrate on the counter until it went to voicemail.

“Mia, seriously, where are you? This isn’t funny.” His voice crackled through the speaker when I finally listened later. “Meredith thinks you overheard something and got the wrong idea. Just come home so we can talk, okay? Don’t be dramatic.”

The wrong idea.

As if there were a right way to interpret I file, I get half of everything.

I slept in broken snatches that night, the kind where dreams and waking blur and your body never quite believes it’s allowed to rest. When the sky turned that specific pre-dawn purple that looks like a bruise healing in reverse, I got up.

Sophia didn’t try to stop me when I packed.

A single duffel bag. Jeans, sweaters, underwear. The framed photo of my parents from the mantle—my mother laughing at some joke just off camera, my father looking at her like she held the whole world in her hands. Drew had always said it made the living room feel “heavy,” like a shrine. I wrapped it in a sweater and tucked it carefully between folded piles of clothing.

I left my wedding rings—both the engagement ring he’d picked out at a jewelry store in Cherry Creek and the simple band we’d exchanged in a courthouse ceremony—on Sophia’s kitchen counter next to the empty bourbon glass. They looked small on the fake marble, like they belonged to another life.

I scribbled a note on one of her sticky pads: Thank you for holding me together while I fell apart.

I didn’t say goodbye. There are some exits that don’t have room for ceremonies.

The highway north out of Fort Collins stretched ahead, long and straight, the mountains watching like witnesses. I merged onto I-25 and just kept going, past the familiar exits, past the outlet mall, past the turnoff for Denver.

The rental billboards and subdivisions thinned as the mountains grew sharper against the sky. I turned west where the interstate branched, then north again, letting my GPS chime uselessly in the background. I shut it off after an hour. The specifics didn’t matter. I only needed one direction: away.

I paid cash for gas at the stations tucked beside rural truck stops, keeping my head down, my shoulders hunched. I turned my phone off completely near a sign that cheerfully announced I was entering Wyoming before I looped back into Colorado on a smaller highway that hugged the base of the Rockies.

By the time I landed in a tiny town wedged against the mountains, three days had passed. I’d eaten in diners, slept in motels where the bedspreads had seen better decades, and lined trash cans with receipts I didn’t want to think about.

The town’s only stoplight blinked yellow all night over an intersection of one main street and one side road. There was a feed store, a bar, a post office, and a diner whose neon sign flickered COFFEE in red letters.

I pulled into the gravel lot out front because my hands were starting to tremble around the steering wheel.

Inside, the diner smelled like bacon grease, coffee, and the lemon cleaner someone had halfheartedly swiped over the counter a few hours earlier. A bell over the door announced my entrance with a cheerful ding that felt offensively optimistic.

I slid into a booth by the window. The waitress, somewhere between forty and ageless, with tired eyes and a pencil behind her ear, poured me a cup of coffee without asking and left a menu I didn’t read.

The couple at the table behind me talked loud enough that I couldn’t help hearing.

“We’re gonna need an extra hand before winter really sets in,” the man said. His voice had a slow, ground-down quality, like he’d been worn smooth by years of wind and work. “Calving late this year. Fences up on the north ridge are shot. I ain’t twenty anymore, Norah.”

His wife snorted softly. “You ain’t been twenty since Reagan, Harlan. Maybe if you hadn’t chased off every hired hand with that charming personality of yours…”

He muttered something. She laughed in that indulgent way people do when they’ve been married long enough to fight and forget it a thousand times over.

“We can’t pay much,” Harlan said after a pause. “But we’ve still got that old cabin. Room and board’s worth something. Long as whoever it is don’t mind hard work.”

I stared into my coffee, watching the thin skin of oil on top quiver when I tapped the table with my fingernail.

I had a trust fund. Investments. A Fort Collins house with blue shutters. On paper, I was someone who should have been sipping wine at a downtown restaurant, not eavesdropping on ranchers talking about spare cabins in God-knows-where, Colorado.

On paper, I had everything.

In reality, I had a duffel bag and a heart that felt like someone had cut it out, dropped it behind a couch cushion, and forgotten it there.

I looked down at my left hand resting on the tabletop. The faint white indent where my wedding rings had been glowed like a tiny, accusing moon.

I have nothing left to lose, I thought.

The waitress came by to refill my cup. My mouth opened before I could second-guess myself.

“Where’s their place?” I nodded subtly toward the couple. “The ranch they’re talking about.”

She followed my gaze, one eyebrow hitching up. “Harlan and Norah Keene? ’Bout twenty minutes up the road, north and west. Everyone around here knows ’em.” A smirk tugged at her lips. “You lookin’ for work, hon?”

I thought about spreadsheets and conference calls and Drew’s voice in my kitchen talking about half. I thought about Meredith’s SUV in my driveway.

“I’m looking for something I can’t lose in a court filing,” I said.

She studied me for a beat, then tipped her chin at the couple. “Then you might wanna say hello.”

My legs felt unsteady as I stood. I walked over to their table, clutching my coffee mug like a shield.

“Excuse me,” I said, heat creeping up my neck. “I’m sorry, I didn’t mean to eavesdrop, but I heard you mention needing help before winter. Are you still… is that still… open?”

The man—Harlan—looked up from his plate, fork pausing mid-air. His eyes were a grayish blue, like river stones. He took me in the way people out here probably take in weather: slow, thorough, measuring what kind of damage you might bring or prevent.

Norah’s gaze followed, softer but no less sharp.

“You ever worked a ranch before?” Harlan asked.

“No,” I said honestly. “But I learn fast. And I’m not afraid of hard work.”

He frowned, as if he could see every blister I didn’t have yet. I had office hands. Trust-fund hands. The most I’d ever lifted regularly was a laptop bag and grocery sacks.

“Where you from?” he asked.

“Fort Collins.” The word tasted like a foreign country. “Originally Denver. Before that… Texas.”

Norah tilted her head. “You running from something, honey?”

I thought of Drew’s laugh, Meredith’s smirk, Tessa’s name.

“I’m running toward something,” I said quietly. “I just don’t know what it’s called yet.”

Norah’s mouth quirked, the barest hint of a smile. “Well. Honest, at least.”

Harlan scraped his fork against the plate, then set it down with a sigh. “Name’s Harlan,” he said, offering a hand rough from decades of work. “My wife, Norah. We got a place up past Mile Marker 18. You really want to work, you can ride up with us now. We’ll see how you do for a week. You quit, we don’t chase. We’re too old for drama.”

“I’m Mia,” I said. His hand swallowed mine, the calluses scraping against my softer skin. “I don’t want drama, either.”

“Everybody says that.” He tossed a couple of bills on the table, stood, and reached for his hat. “Come on then, Fort Collins. Let’s see if you last longer than the last kid.”

The drive out to the Keene ranch felt like leaving the planet. Pavement gave way to gravel, then to packed dirt, the truck rattling over washboards. Lodgepole pines thickened along the roadside. The air tasted cleaner, sharper, free of exhaust and office-building recycled chill.

The ranch unfolded in a valley between low hills, fences cutting the land into long, uneven rectangles. An old white farmhouse sat at the center like a weary queen, flanked by two weathered barns and a scattering of outbuildings. A faded sign at the start of the drive read KEENE RANCH in crooked hand-painted letters.

I slept that night in a one-room cabin with a narrow bed, a woodstove, and walls that let in every whisper of wind. I lay awake listening to coyotes yip in the distance and my own heart beating too loudly.

The next morning, my body began to discover new ways to hurt.

Harlan woke me before dawn by banging on the cabin door. “Coffee’s on in the kitchen,” he shouted. “Fence line, twenty minutes.”

I forced my eyes open, shuffled into jeans and a sweater, shoved my feet into boots that weren’t broken in yet, and stumbled through the cold to the main house.

The kitchen was warm and smelled like coffee and frying bacon. Norah slid a plate onto the table in front of me. Eggs, thick-cut bacon, biscuits that steamed when you tore them open.

“Eat,” she said. “You’re gonna need it.”

I shoved food into my mouth mechanically, too tired to taste. Harlan handed me a pair of gloves and an old jacket that smelled faintly of hay. “North pasture,” he said. “We’re resetting posts. Ever swung a post maul?”

“What’s a post maul?” I asked.

He sighed. “Figured.”

Hard work turned out to be shorthand for: everything hurts and you do it anyway.

We hauled posts, hammered them into rocky ground, wrestled rolls of barbed wire that seemed determined to fight back. The cold slipped under my borrowed jacket, into the hollows of my collarbones, the backs of my knees. My palms blistered by mid-morning. By afternoon, they split.

Every night that first week, I fell into the narrow bed in the cabin so tired my bones buzzed. Sleep came like a dropped curtain, black and absolute.

And still, in the dark, Drew’s voice sometimes surfaced.

Three times today, Mere. Three.

My mind replayed the kitchen, the laughter, the words half of everything on a loop. The hurt didn’t feel like a wave crashing. More like a stone lodged somewhere deep in my stomach, heavy and immovable.

Norah never asked questions. She just fed me. More eggs, more biscuits, more coffee. Sometimes stew that tasted like someone had put a whole winter’s worth of comfort into a pot.

Harlan barked orders like he’d known me forever, correcting my grip on tools, pointing out rotten posts, showing me how to read the land and the sky. When he snapped, “You’re doing that wrong,” it didn’t feel personal. It felt… oddly safe. Reliable.

Their son was away helping a neighbor on another ranch. I was grateful. The last thing I wanted was anyone my own age looking too closely at the way my hands shook sometimes when the wind shifted just right.

One afternoon, a storm rolled down off the peaks fast enough to make the horses skittish and the birds scatter. The wind rattled the barn roof. I was alone in the far pasture with a roll of barbed wire that had decided it would rather strangle me than go where it was supposed to.

I wrestled with it, cursing under my breath. The glove on my right hand snagged on a barb and tore, fabric ripping with a small, traitorous sound. Before I could adjust, the wire slid, and a strand caught my exposed palm.

It wasn’t a dramatic injury. No arterial spray, no cinematic gushing. Just a clean slice across the pad of my hand. Blood welled up, bright against the rust-dull metal and the gray afternoon.

I stared at it, dazed. It didn’t even hurt at first, not like I expected. The pain was a delayed echo, arriving a second later.

I watched a drop of blood fall, darkening a patch of dry dirt. Then another. And another.

Something inside me—something I hadn’t even realized was still clenching—finally cracked.

I slid down the nearest fence post until I was sitting in the cold mud, back braced against the rough wood, hand bleeding into a fist I couldn’t unclench.

The sobs came out of nowhere. No polite tears. No dignified sniffles. Ugly, wrenching sounds ripped out of my chest like someone had reached in and twisted.

I cried for the girl who’d once believed love was a promise kept instead of an opportunity cashed out.

I cried for every night I’d lain awake next to Drew, staring at the ceiling fan shadows on our Fort Collins bedroom ceiling, wondering what, exactly, I had done wrong to make him roll away.

I cried for my parents, gone in a flash of metal and fire over Texas, and for the way I’d handed my heart to the first man who offered to help me carry the grief.

I cried because the one person I’d let into the space they left behind had stood in our kitchen and measured my worth in dollars and real estate and decided I was a good investment to liquidate.

When the storm in my chest finally spent itself, the actual storm had blown past. The clouds were tearing apart overhead, streaks of blue showing through.

My hand had stopped bleeding. The cut stung. I wrapped it clumsily in the bandana I kept in my back pocket, using my teeth to knot the fabric tight.

Then I stood up, picked up the barbed wire, and went back to work.

The wire didn’t feel quite so heavy anymore.

That night, Harlan didn’t mention the makeshift bandage. Norah gave me an extra scoop of potatoes and slid a jar of homemade pickles closer to my plate like this was some kind of consolation prize for surviving myself.

After dinner, I sat on the cabin step, staring at the dark outline of the barn against a sky full of stars. The cut in my palm throbbed in time with my heartbeat.

Norah appeared without a sound, the door creaking only slightly as she eased it open. She sat down beside me like she’d been invited. Her joints popped quietly as she bent.

She pressed a mug into my hands. The liquid inside smelled like honey and whiskey and steam.

“You’re carrying a lot for someone so quiet,” she said, eyes on the horizon.

I huffed out something that might have been a laugh if it weren’t so shaky. “I’m not quiet,” I said. “I’m just done talking to people who never listened.”

Norah nodded, as if that was the most reasonable thing she’d heard all week. “Some hurts don’t need words,” she murmured. “They just need time. And honest work.”

I took a sip of the drink. It burned all the way down, spreading warmth through the cold spaces.

“I keep thinking I should be angrier,” I admitted. “I’m not. Not really. I just feel… hollow.”

“Hollow can be useful.” She rested her elbows on her knees, hands clasped loosely. “Means there’s room for something new to grow.”

I wanted to believe her. I wasn’t sure I could. Not yet.

A few days later, Nolan came home.

I saw him first from a distance, just a figure on horseback cresting the rise beyond the lower pasture. The afternoon light caught on his hat brim, turning its edge into a gold halo. He rode with the kind of easy balance that only comes from decades of practice or a childhood spent on a saddle.

I pretended to be very busy stacking feed sacks until he pushed the barn door open.

He stopped short when he saw me, one hand on the latch, the other still gloved.

“Dad said we had help,” he said, voice low and a little amused. “Didn’t say it was someone half my size wrestling a fifty-pound sack like it’s trying to rob her.”

“Your dad’s not big on details,” I answered, the words slipping out before I could censor them.

The corner of his mouth twitched. He stepped forward, took the sack from my hands like it weighed nothing, and slung it up onto the stack.

Up close, I could see he was a few years older than me. Maybe late thirties. Dark hair that curled just enough at the nape of his neck to hint at trouble. Eyes the color of storm clouds behind mountains, gray with something unreadable.

He glanced at my bandaged hand. “You eat yet?” he asked.

I shook my head.

“Come on, then.” He jerked his chin toward the farmhouse. “Mom’ll have my hide if I let you starve.”

At supper, he sat across from me at the table. Norah loaded his plate like she’d been waiting weeks to do it.

He didn’t fill the silence with small talk. When I passed the potatoes, our fingers brushed. He didn’t make a joke or an apology. Just met my eyes for half a second and moved on.

After the meal, when Harlan started in on a story about a bull that had taken out half a fence back in ’98, Nolan pushed his chair back and stood.

“I’ll walk you back,” he said.

“It’s, like, twenty steps,” I protested, nodding toward the cabin visible through the back window.

“Mom’ll sleep better if I do it,” he said with a shrug. “You don’t want to be the reason she doesn’t sleep.”

It was hard to argue with that.

We walked in companionable quiet. The sky was clear, the Milky Way splashed overhead so boldly it looked fake. City girl awe tugged at my chest, even as my head felt too full.

At the cabin door, Nolan stopped.

“Whatever you’re running from,” he said, eyes steady on mine, “it doesn’t get to follow you here unless you’re the one carrying it in.”

I swallowed. His words hit something sore and tender.

“You look strong enough to set it down,” he added, almost gently.

He had no idea what I was carrying. The trust, the marriage, the betrayal, the weight of two dead parents and one living husband who had turned me into a math problem.

I wanted to tell him all of it. I also wanted to slam the door and never speak again.

“Good night, Nolan,” I managed instead.

“Good night, Mia,” he said.

Inside, I leaned my forehead against the door for a long time after I closed it, feeling that stone in my stomach shift just a fraction of an inch.

Winter doesn’t arrive all at once in the Rockies. It creeps in. First the mornings bite harder. Then the snow sticks instead of melting by noon. Breath becomes visible. Mud freezes. Everything simplifies to survival.

By the time the year turned, my hands no longer looked like they belonged to someone who spent her days at a keyboard. Calluses built themselves up in the places that had once blistered. The scar on my palm from the barbed wire faded from angry red to pale pink.

My phone stayed off, buried in the bottom of my duffel like an artifact from a civilization I’d fled.

Sophia was the only loose thread to that world. I checked in from the diner once a month using the payphone in the corner, feeding it coins like sacrifices.

The last time I called, she was brisk and efficient, the way she got when things were under control.

“He’s frantic,” she said. “Filed a missing person report in Fort Collins. The cops came by my office.”

My throat tightened. “What did you tell them?”

“The truth. That you’re alive, that you left voluntarily, that there was no foul play.” She paused. “And then, just to shut everyone up, I emailed a photo of you to the detective. Dated it with last week’s newspaper from here. He closed the case.”

Relief and something like sadness tangled in my chest.

“There’s more,” she added. “Drew lawyered up. Filed for divorce. The petition is… aggressive. He wants half the trust, the house, alimony. Basically everything except your blood type.”

I picked at a chip in the payphone’s paint. “He can want.”

“It’s still a problem,” she said. “On paper, you’re missing meetings. Foundations get nervous when their trustees drop off the map.”

“I’ll call the attorney we talked about,” I said. The expensive one in Denver. The one who had looked at me in our first consultation, heard the words community property, and smiled like a shark. “Tell him it’s time to earn his retainer.”

“It’s more than that,” Sophia said. Her voice softened. “How are you? Really?”

I looked out the diner window at the single blinking yellow stoplight. At the faded blue pickup truck rattling past. At the mountains, steady and indifferent.

“I think,” I said slowly, “I might still be alive.”

She laughed, a wet sound like tears. “That’s a start, babe.”

True to my word, I called the attorney from the payphone the next day. He laid out my options in calm legalese. Trust structure protections. Commingling issues. Statutes and precedents. We agreed on a strategy that was, in his words, “polite but unforgiving.”

“Men like your husband,” he said, “tend to fold when they realize they’re not holding the cards they think they are.”

As winter tightened its grip, Nolan and I fell into a rhythm that was both utterly ordinary and quietly monumental.

We rode fence lines together, checked water troughs, moved cattle. Sometimes we talked. Sometimes we didn’t. He told me about summers spent fixing everything that broke faster than his parents could afford to replace it. About a sister in vet school in Montana. About a fiancée he’d once had and then hadn’t, because she preferred town to pasture and he preferred sky to street.

I told him little pieces of myself. My parents’ plane. The lawyer in Texas who’d read me their will in a room that smelled like old books and lemon oil. The first night in Fort Collins when I’d walked through the echoing, empty house and felt lonelier than I ever had in my life.

I didn’t tell him about Drew. Not yet. The words felt too radioactive.

One afternoon in late March, the sky did that thing where it looked like it couldn’t decide between rain and sun. We saddled up to check the high pasture for strays. Halfway out, the clouds made up their minds. Cold rain came down in sheets, turning the trail to slick mud.

“Cabin,” Nolan shouted over the rush of water.

We veered off toward a small structure I’d barely noticed before. It was an old line cabin—four walls, a roof, a door that stuck when you shoved it. Inside smelled like pine pitch and dust and the ghost of coffee boiled too long on a stove long since hauled away.

Nolan got a fire going in the small stone hearth with the kind of ease that spoke of many such storms. I stood there dripping, hair plastered to my neck, jeans clinging uncomfortably, watching my breath puff white in the cold air.

We sat on opposite sides of the narrow room at first, steam rising from our clothes. The silence was not the brittle, anxious kind I’d grown used to in my Fort Collins kitchen. It was thick, waiting.

“Tell me the rest,” Nolan said finally.

It wasn’t a question. More like a gently opened door.

So I walked through it.

I told him everything. The October evening. Meredith’s car in my driveway. The smell of the cinnamon candle. Drew’s voice floating down the hallway. Three times today. The word trust spoken like a jackpot. Community property said like a punchline.

I told him about the hallway in the dark, the wine bottle digging into my palm, the way my life had pivoted on a dropped set of keys.

I told him about Sophia’s couch, about moving money with hands that wouldn’t shake, about the drive north with my phone turned off and my heart strapped to the roof of the car.

When I finished, the rain was hammering the tin roof so loudly it was hard to hear myself breathe.

Nolan didn’t offer pity. Didn’t cluck his tongue or say, “What a jerk,” or any of the other easy things people say when they don’t know what else to do.

He just reached across the space between us.

His fingers brushed my cheek. He plucked something from my skin—mud or ash, I wasn’t sure. Then he took the bandana out of my pocket, the same one I’d wrapped around my bleeding hand months ago, and used one corner to gently wipe a streak of dirt from my face.

“I’m glad you left,” he said.

The simplicity of it hit me harder than any lecture.

“I’m glad you stayed,” I heard myself say.

Something inside my chest, something that had been clenched since the day my parents’ plane went down, opened.

I leaned across the gap between us. He met me halfway.

The kiss wasn’t soft. It wasn’t tentative. It tasted like woodsmoke and rain and four months of holding myself together with nothing but stubbornness and fence posts.

We didn’t make it back to the ranch until full dark. Norah took one look at us coming in late for dinner, hair damp, wearing the same clothes as that morning, and simply poured two extra cups of coffee. She didn’t comment. She didn’t need to.

A week later, Sophia called the diner during lunchtime. The waitress waved me over with the receiver.

“Your fancy lawyer earned his money,” she said as soon as I picked up. “The divorce papers just landed on my desk.”

My stomach flipped. “And?”

“And your soon-to-be ex is furious. He’s trying to make you out to be the villain in every way possible. Says you ‘abandoned’ the marriage, that you’re ‘unwell,’ that you ‘cleaned him out.’ ”

“I left him thirty-one thousand dollars,” I said automatically.

“Well,” she said dryly, “I didn’t point that out. I told him all communication goes through your attorney now. Speaking of which, the settlement demands are… ambitious.”

She read them off. Half the trust. The Fort Collins house. Spousal support. Attorney’s fees. It sounded less like a divorce and more like a smash-and-grab.

I went back to the payphone that afternoon, quarters lining up like soldiers on the ledge as I called my lawyer.

“Tell him he gets fifty thousand dollars,” I said. My voice sounded calm, even to my own ears. “And nothing else.”

“That’s generous,” he said. “You don’t legally owe him anything near that, given how cleanly your assets were kept separate.”

“It’s not generosity,” I said. “It’s severance pay. He gets fifty thousand to go away and build whatever life he wants with whoever he wants. In exchange, he signs whatever you put in front of him. No appeals, no delays.”

“And if he refuses?” the lawyer asked.

I looked up at the mountains. At the thin line of snow still clinging to the highest ridges. At the hawk circling on an invisible current.

“Then I disappear again,” I said. “And this time, he never finds me. He can spend the rest of his life chasing a ghost through court filings. I really don’t care.”

On Friday, the lawyer called.

“He signed,” he said, satisfaction threaded through every syllable. “The papers will be final by Monday. The check for fifty thousand is being sent to your forwarding address.”

Sophia texted me a photo of the check when it arrived. I stared at the screen in the diner’s parking lot, the numbers printed out in neat black ink.

Then I endorsed the check over to a women’s shelter in Fort Collins.

“Poetic,” Sophia texted when I sent her the confirmation. “I approve.”

That night, Nolan found me sitting on the ranch house porch steps, staring up at a sky smeared thick with stars. The air had lost its winter bite. Spring was whispering at the edges of everything, green creeping in where there had only been brown and white for months.

“It’s done,” I said when he sat down beside me, shoulder to shoulder.

He didn’t say, “Congratulations,” or “I’m sorry,”

News

I was at TSA, shoes off, boarding pass in my hand. Then POLICE stepped in and said: “Ma’am-come with us.” They showed me a REPORT… and my stomach dropped. My GREEDY sister filed it so I’d miss my FLIGHT. Because today was the WILL reading-inheritance day. I stayed calm and said: “Pull the call log. Right now.” TODAY, HER LIE BACKFIRED.

A fluorescent hum lived in the ceiling like an insect that never slept. The kind of sound you don’t hear…

WHEN I WENT TO MY BEACH HOUSE, MY FURNITURE WAS CHANGED. MY SISTER SAID: ‘WE ARE STAYING HERE SO I CHANGED IT BECAUSE IT WAS DATED. I FORWARDED YOU THE $38K BILL.’ I COPIED THE SECURITY FOOTAGE FOR MY LAWYER. TWO WEEKS LATER, I MADE HER LIFE HELL…

The first thing I noticed wasn’t what was missing.It was the smell. My beach house had always smelled like salt…

MY DAD’S PHONE LIT UP WITH A GROUP CHAT CALLED ‘REAL FAMILY.’ I OPENED IT-$750K WAS BEING DIVIDED BETWEEN MY BROTHERS, AND DAD’S LAST MESSAGE WAS: ‘DON’T MENTION IT TO BETHANY. SHE’LL JUST CREATE DRAMA.’ SO THAT’S WHAT I DID.

A Tuesday morning in Portland can look harmless—gray sky, wet pavement, the kind of drizzle that makes the whole city…

HR CALLED ME IN: “WE KNOW YOU’VE BEEN WORKING TWO JOBS. YOU’RE TERMINATED EFFECTIVE IMMEDIATELY.” I DIDN’T ARGUE. I JUST SMILED AND SAID, “YOU’RE RIGHT. I SHOULD FOCUS ON ONE.” THEY HAD NO IDEA MY “SECOND JOB” WAS. 72 HOURS LATER…

The first thing I noticed was the silence. Not the normal hush of a corporate morning—the kind you can fill…

I FLEW THOUSANDS OF MILES TO SURPRISE MY HUSBAND WITH THE NEWS THAT I WAS PREGNANT ONLY TO FIND HIM IN BED WITH HIS MISTRESS. HE PULLED HER BEHIND HIM, EYES WARY. “DON’T BLAME HER, IT’S MY FAULT,” HE SAID I FROZE FOR A MOMENT… THEN QUIETLY LAUGHED. BECAUSE… THE REAL ENDING BELONGS TΟ ΜΕ…

I crossed three time zones with an ultrasound printout tucked inside my passport, my fingers rubbing the edge of the…

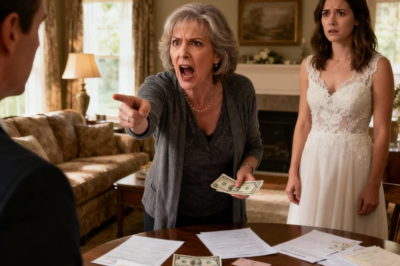

“Hand Over the $40,000 to Your Sister — Or the Wedding’s Canceled!” My mom exploded at me during

The sting on my cheek wasn’t the worst part. It was the sound—one sharp crack that cut through laughter and…

End of content

No more pages to load