The plane dropped through a layer of gray cloud and the world outside my window sharpened into hard lines—runway lights, service roads, the slow crawl of baggage carts. My hands were steady on the armrests, but my ribs felt too small for my lungs. The folder sat on my lap like it had weight beyond paper. Not because it was thick. Because every page inside it was a piece of reality that didn’t care what my parents wanted the world to believe.

As soon as we touched down, my phone woke up like it had been holding its breath. Bars returned. Notifications stacked. A voicemail from a number I didn’t recognize. Three missed calls from my mother. An email from “Grant & Linda Holloway – Counsel” with a subject line that looked like a threat wearing a tie: NOTICE OF INTENT TO PROCEED.

I didn’t open it.

I stood when the seatbelt sign clicked off, but I didn’t rush. Rushing is what they wanted. Rushing makes you sloppy. Sloppy makes you look like the version of you they’re trying to sell.

In the jet bridge, the air smelled like recycled metal and cheap carpet cleaner. People streamed past me toward the terminal like their lives were normal and linear. I let them go. I walked at a pace that said I belonged in my own body. I kept the folder pressed to my side, a habit from childhood when you learned to protect what mattered by holding it close enough that you could feel it.

At baggage claim, I didn’t wait for anything. I’d traveled light on purpose. One carry-on, one folder, one straight shot from airport to courthouse town. Outside, the evening air was sharp in a way that made my skin feel awake. I stood on the curb, called the rideshare, and watched taillights move like red stitches in the distance.

The driver who picked me up was a man in his fifties with a baseball cap and a face that looked like he’d listened to a thousand airport stories and never judged any of them. “Where to?” he asked.

I told him the name of the hotel.

He glanced at me in the rearview mirror and then at the folder on my lap. “Court stuff?” he asked, casual.

“Family stuff,” I said.

He made a sound that meant the same thing. “Those are the worst kind.”

I didn’t talk the whole ride. I watched the landscape change from airport sprawl to low-lit streets, then to the darker stretch beyond the city where the road feels like a corridor between decisions. My phone buzzed again. I kept it face down. The courthouse drama was paused until morning, but my parents didn’t know how to stop pushing once they’d started. People like them confuse pressure with power. They think if they keep squeezing, they’ll get something out of you.

The hotel was one of those places that tries to look warm with yellow light and carpet patterns that pretend to be art. I checked in with a credit card my parents couldn’t touch, took the key, and went straight to the room. No room service. No TV. No distractions. I locked the door, set the folder on the nightstand, and stared at it like it might try to disappear if I looked away.

Then I finally opened my phone.

My mother’s texts were lined up like bullets.

You embarrassed us.

You’re making this ugly.

Turn around. You will regret it.

We’re trying to protect you.

You are not thinking clearly.

There it was again. The same phrase that had followed me from airport security to airline counter to a motion filed in court: not thinking clearly. They didn’t want to prove I was wrong. They wanted to prove I was unfit to even speak.

I scrolled up. There was a message earlier from her—days ago—when my grandfather had barely been gone a week.

If you insist on showing up, we will handle it.

I stared at that line until my eyes burned, because it wasn’t metaphorical anymore. It was a blueprint. Handle it had meant uniforms and phone calls and paper filings. Handle it had meant using systems that weren’t built for family wars but could be hijacked by anyone fluent in the right vocabulary.

My father’s email sat unopened in my inbox like a closed door with yelling behind it. I left it that way.

Instead, I opened the photos I’d taken on the plane of the CAD printout and dispatch summary from the night my grandfather died. I enlarged the lines until the pixels softened. The page was clinical: case number, time stamps, caller info, brief notes typed by someone who didn’t know us and didn’t care. And still, there it was—the thing that had made my stomach tighten the first time I saw it. A short line in the narrative field, the kind of detail dispatchers include without realizing it could blow up a family.

SUBJECT’S DAUGHTER ON SCENE. SON-IN-LAW NOT PRESENT. CALLER ADVISED SUBJECT REQUESTED ATTORNEY EARLIER IN DAY.

My throat tightened. Son-in-law not present. That meant my father wasn’t there when the call came in. That meant he wasn’t the panicked, devoted caretaker he’d been portraying to anyone who would listen. And the last line—requested attorney earlier in day—meant my grandfather had wanted legal help before anything happened.

Before he died. Before my parents swooped in with their grief costumes and their “We’ll handle it” voices.

I sat on the edge of the hotel bed with the phone in my hand and felt the quiet rage of clarity. Not the loud kind that makes you do something reckless. The cold kind that makes you do the right thing with surgical precision.

I called Elliot Lane again. It was late. I didn’t expect an answer.

He answered anyway, voice low. “You landed.”

“Yes.”

“How are you holding up?”

I looked at the folder. “Like I’m wearing someone else’s life for a night.”

“You did well today,” he said. “I mean that. You didn’t give them the reaction they wanted.”

“What happens tomorrow?” I asked.

“Tomorrow,” he said, “we walk in with your evidence already in the judge’s hands. Your parents will try to pivot. They’ll argue it was all misunderstanding, concern, fear. But the timeline is a fingerprint. It’s hard to unmake.”

“And the referral?” I asked.

Lane exhaled softly. “The judge said he’s referring conduct. That could mean a few things—possible misuse of emergency systems, false reporting, interference. It doesn’t guarantee charges. But it’s an official flag. It tells everyone: I saw what you did. Don’t do it again.”

“What about the temporary appointment they wanted?” I asked.

“Denied—for now,” he said. “Which matters. Because it keeps them from grabbing the steering wheel overnight.”

I swallowed. “They’ll come for me another way.”

“Yes,” he said, and didn’t sugarcoat it. “So we make the record as clean and complete as possible. We anchor everything in documents, not feelings.”

I stared at my phone. “My mother threatened guardianship.”

“I saw the screenshots,” he said. “That’s a separate fire. If they try to go that route, we address it. But tomorrow is the probate hearing. Tomorrow we keep your seat from being empty.”

When we ended the call, I didn’t feel calmer. I felt ready. Ready isn’t peace. Ready is the moment you stop bargaining with the fact that you’re in a fight.

I slept in stretches, waking every couple of hours like my body didn’t trust the night not to change the rules again. Each time I woke, I looked at the folder on the nightstand. It stayed. It didn’t grow legs. It didn’t vanish. It just waited.

At dawn, I showered until the water ran cold. I dressed in the plainest, most respectable outfit I owned—dark slacks, a simple blouse, hair pulled back. Not because I wanted to perform for the court, but because I refused to let my parents point at anything and call it unstable. I wore no bright lipstick. No dramatic jewelry. I looked like a woman who had come to be counted.

In the lobby, I ordered black coffee I barely tasted. My hands didn’t shake. They didn’t have the energy. They had turned their trembling into purpose.

Elliot Lane met me outside the courthouse a little before nine. The building sat like a square promise in the morning light—stone walls, wide steps, the American flag doing its constant, indifferent flutter. Lane looked the same as always: suit pressed, eyes alert, the kind of man who has learned how to stay calm in rooms where other people lose their futures.

He nodded once when he saw me. “You ready?”

“No,” I said, and meant it. “But I’m here.”

“That’s what matters,” he replied.

We walked up the steps together. The air smelled like old paper and cold floors as soon as we entered. The courthouse had its own sound—shoes echoing, voices muted, the hush of people who know the walls remember.

In the hallway outside the courtroom, I saw them.

My parents.

My father stood with his back straight, suit expensive, hair perfect. My mother sat on a bench with her hands folded like prayer, eyes already a little glossy as if she’d pre-loaded her tears for the audience. Their attorney hovered near them, speaking in a low, controlled voice. The three of them looked like a tableau designed to tell a story before anyone spoke: concerned parents, difficult daughter, responsible counsel.

When my mother saw me, her face brightened for half a second with something that looked like relief—then tightened when she remembered her script.

My father’s eyes flicked to Lane, then to me. He smiled the way people smile when they want you to think they’re not threatened. “Nina,” he said, like he was greeting a child who’d wandered off.

Lane didn’t stop walking. Neither did I.

We took our seat. Lane set his binder on the table with a soft, deliberate thump. The folder stayed in my hands.

My mother leaned toward me as if she was going to whisper something loving, something private. But her voice was low and sharp. “Why are you doing this?” she asked. “You’re making us look like monsters.”

I looked at her. Her eyes were wet, but her gaze was steady. That’s what gave her away. Real tears blur you. Her tears were props.

“You did that,” I said quietly. “Not me.”

My father’s jaw flexed. “Lower your voice,” he murmured, as if he still had the authority to discipline me in public.

Lane turned slightly. “Any communication should go through counsel,” he said to my parents’ attorney, calm and icy.

The attorney nodded with a polite smile that didn’t reach his eyes. “Of course.”

The courtroom doors opened. People filtered in like they were boarding a different kind of flight—one where the destination was a decision. The judge entered a moment later, robe hanging heavy, face unreadable. Everyone rose. The sound of chairs scraping the floor was a single, collective inhale.

We sat when told.

The clerk called the case. Estate of Harold M. Holloway.

My father’s spine straightened like he was about to accept an award.

The judge’s eyes moved over the room, lingering just long enough on my parents, then on me. Not judgment. Assessment.

“Before we proceed,” the judge said, voice flat, “I want to address the events of yesterday.”

My father’s face didn’t change, but the tension in his shoulders did. He was bracing.

The judge looked down at a sheet in front of him. “I have reviewed the supplemental materials submitted regarding an airport stop, an airline reservation cancellation, and a motion filed by counsel for Mr. and Mrs. Holloway that contained representations about those events.”

The courtroom went still. Even the air seemed to pause.

“I will be clear,” the judge continued. “This court will not be used as an instrument of obstruction.”

My mother made a soft sound, as if she were wounded by the word obstruction. My father stared straight ahead.

The judge’s gaze shifted to their attorney. “Counsel,” he said, “the motion filed yesterday stated that Miss Holloway was removed from airport security in handcuffs for threat-related behavior. The exhibit provided indicates the opposite.”

The attorney rose smoothly. “Your honor, we filed in good faith based on information provided by our clients.”

“Which appears to have been false,” the judge said, still calm. “I caution you now. This court expects accuracy. If you put something in my record that is not true, you will answer for it.”

My father finally reacted. “Your honor—”

The judge held up a hand without looking at him. “Mr. Holloway,” he said, “you will speak when called upon.”

There it was. The first crack in my father’s usual control. Not just because he was told no. Because he was told no by a person in a robe with a gavel and a record that lasts longer than charisma.

The judge turned his attention back to the case itself. “Now,” he said, “we are here regarding the administration of the estate and issues surrounding the validity of the most recent will.”

Lane rose. “Your honor,” he began, “we appear on behalf of Miss Nina Holloway, named beneficiary, and we also appear as counsel of record previously engaged by the decedent.”

The judge nodded. “I see that.”

My parents’ attorney stood next. “Your honor, my clients have concerns regarding the decedent’s capacity at the time of the will’s execution and concerns regarding undue influence.”

There it was. The phrase they’d been practicing. Capacity. Influence. Words that turn grief into a contest.

The judge looked at me. “Miss Holloway,” he said, “you are present.”

“Yes, your honor.”

“Good,” he replied simply, and something in my chest loosened. Not because I trusted the outcome. Because I was no longer being discussed like a rumor.

The hearing moved the way hearings do—slow, procedural, full of words that pretend they’re neutral while they choose sides. My parents’ attorney laid out their argument with calm confidence: that my grandfather had been confused, vulnerable, “not fully himself.” That I had “isolated” him. That the will change was suspicious. That my parents had “always been the primary support.”

Lane listened without interrupting, his face a mask of polite patience. When it was our turn, he stood and began to dismantle their story with the same tool they’d tried to use against me: record.

He referenced dates. He referenced signatures. He referenced witnesses. He referenced the attorney’s notes from the day the will was executed.

Then he said, “Your honor, we would also like to introduce as an exhibit a CAD printout and dispatch summary from the night of the decedent’s death.”

My father’s head lifted sharply.

The judge’s eyes narrowed. “On what basis?” he asked.

“Capacity and presence,” Lane replied. “Opposing counsel has argued the decedent was confused and easily influenced. This document is a third-party contemporaneous record. It includes not only timing, but the identity of individuals present and notes reflecting the decedent’s requests earlier that day.”

The judge held out a hand. The clerk took the document from Lane and brought it forward.

My father’s mouth tightened. My mother’s hands clenched in her lap, then loosened like she remembered she was being watched.

The judge read in silence for a moment. The courtroom held its breath around him.

Then he looked up. “This indicates,” he said slowly, “that the decedent requested an attorney earlier in the day.”

My father’s attorney shifted. “Your honor, that could mean a variety of things—”

“It could,” the judge agreed. “Or it could mean exactly what it says.”

He scanned the page again. “And this notes,” he continued, “that the subject’s daughter—Miss Holloway—was on scene. And that the son-in-law was not present.”

My father’s face went pale by half a shade. It was subtle. But I saw it. I knew the exact moment his internal story collided with a neutral line typed by a stranger.

My father’s attorney stood. “Your honor, the absence of a person at a particular moment doesn’t—”

The judge lifted his eyes. “Counsel,” he said, “I am aware of what absence can and cannot prove. But I am also aware of what your clients have represented to this court and to other agencies in the last twenty-four hours.”

Silence. Thick, heavy silence.

My mother’s mouth opened slightly like she might cry, then closed when she realized tears wouldn’t rewrite a dispatch log.

The judge set the paper down. “Miss Holloway,” he said, “I have a question.”

“Yes, your honor.”

“Why,” he asked, “do you believe your parents attempted to prevent you from appearing yesterday?”

The question was simple. But it was a trap if I answered the wrong way. If I made it emotional, I would become the unstable daughter they’d promised the world.

I took a breath. I kept my voice calm. “Because,” I said, “an empty seat makes it easier to tell a story without contradiction. And because they want to be appointed to control the estate before the court hears from me.”

Lane’s hand moved slightly, approving. Not dramatics. Just confirmation that I’d kept it clean.

The judge nodded once. He turned to my parents. “Mr. Holloway,” he said, “Mrs. Holloway. Do you deny that you initiated contact with airport police and the airline regarding your daughter’s travel?”

My father stood. His suit looked like armor. His voice was steady, but there was a faint edge in it now. “Your honor,” he said, “we were concerned. We thought she might do something irrational. She’s been… unpredictable.”

There it was. The word he wanted to plant like a flag.

The judge’s gaze sharpened. “Concern,” he said, “does not authorize you to make false statements. And it does not authorize you to interfere with court proceedings.”

My father’s jaw flexed. He tried to smile again, but it didn’t land. “We didn’t interfere,” he said. “We were trying to protect—”

The judge leaned forward slightly. “Protect the public from a probate hearing?” he asked, and the line landed like it had yesterday. Only now it was sharper, because I was in the room to hear it.

My father’s face tightened. My mother began to cry softly, shoulders trembling. It was a performance with muscle memory. But something was different in the room now. The judge wasn’t watching her. He was watching the record.

Lane stood again. “Your honor,” he said, “given the conduct already described, we request that the court appoint a neutral third-party personal representative rather than either party, at least temporarily, to prevent further interference and preserve assets.”

My father’s attorney objected immediately. “Your honor, my clients are the decedent’s next of kin, they are responsible, they are—”

The judge lifted a hand. “I have heard enough,” he said.

He looked directly at my parents. “You attempted to manipulate external systems—law enforcement, an airline, and this court—to create an advantage in a civil proceeding. That is not responsible. That is not credible. And it will not be rewarded.”

My mother’s crying faltered for half a second at the word credible.

The judge turned to the clerk. “I am continuing this matter for evidentiary hearing regarding the will contest,” he said. “In the interim, I will appoint a neutral administrator from the court’s list.”

My father’s head snapped up. “Your honor—”

The judge’s voice didn’t rise, but it hardened. “Mr. Holloway,” he said, “sit down.”

My father sat.

I felt something inside me shift—not triumph, not even joy. Something steadier. Like a floor that had been missing under my life had finally been built.

The judge continued, laying out terms with the calm certainty of someone who knows exactly where power belongs. “All parties will cease direct contact that could be construed as harassment or interference. All communications go through counsel. Any further attempts to involve law enforcement or third parties on false pretenses will be addressed swiftly.”

He looked at my parents’ attorney. “Counsel, you will produce any records related to yesterday’s airport call and airline cancellation. And you will amend your motion to reflect accurate facts. Failure to do so will be considered by this court.”

The attorney nodded, his smile gone.

Then the judge’s eyes moved to me. “Miss Holloway,” he said, “you will have an opportunity to be fully heard. Not today, but soon. This court will proceed on evidence.”

“Yes, your honor,” I said, and my voice didn’t break.

My father stared at me like he didn’t recognize me. Like I’d stepped out of the role he’d assigned and become something he couldn’t control with tone and vocabulary.

The judge adjourned. People stood. Chairs scraped. The room exhaled.

In the hallway, my mother rushed toward me like she was worried about my wellbeing. Her eyes were red now for real—whether from emotion or frustration, I couldn’t tell. She reached for my arm. “Nina,” she whispered, “please. We’re family.”

I stepped back, not dramatically, just enough that her hand met air.

Lane placed himself between us gently, professionally. “All communication through counsel,” he said again.

My father’s voice cut through. “You’re doing this to punish us,” he snapped. His mask had slipped. The concerned father was gone. The angry man was standing there with his entitlement exposed.

I looked at him. “No,” I said quietly. “I’m doing this to stop you.”

His eyes narrowed. “Stop me from what?”

I didn’t answer with a speech. I didn’t say inheritance, or control, or cruelty. I let the silence do what silence does when it’s backed by a court record. I turned and walked away with Lane beside me, my folder tucked under my arm like a spine.

Outside, the sun was brighter than it had been an hour ago, as if the world didn’t care what just happened inside. The flag still moved in the wind. Cars still passed. People still went to lunch and bought gas and argued about nothing.

Lane stopped at the bottom of the courthouse steps. “You did good,” he said again, softer this time. “You stayed clean. You stayed factual. You let the evidence speak.”

I nodded, because if I tried to speak, my throat would have done something humiliating like tighten.

“What happens now?” I asked.

“Now,” he said, “they will try to pivot. They may try to apologize in a way that blames you. They may try to negotiate. They may try another tactic.”

“And the referral?” I asked.

“That’s in motion,” he said. “It may take time. But they can’t unring the bell. Yesterday is in the record. Today is in the record. And records have a way of following people who thought they were untouchable.”

I stared at the courthouse doors. “My grandfather wanted me here,” I said, the sentence coming out before I could polish it.

Lane’s gaze softened. “I believe that,” he said. “And you honored it.”

When he left, I sat in my car for a long moment without starting the engine. I didn’t cry. Crying would have been easy. Crying would have been release. What I felt was heavier. It was the slow recognition that the story of my life had been narrated by my parents for so long that even when the court finally told them no, part of me still expected the punishment afterward.

My phone buzzed.

A text from an unknown number.

You think you won.

I didn’t reply.

Another buzz. This time an email from the court-appointed administrator’s office, introducing themselves, outlining next steps, requesting documents, confirming that the estate would be handled neutrally pending further hearings.

Neutral. That word looked like sunlight.

I drove back to the hotel and sat at the desk in my room, spreading papers out like I was building a map. Not because I liked paperwork. Because I had learned something in the last twenty-four hours: my parents’ favorite weapon wasn’t yelling. It was the creation of a version of reality that sounded official.

So I made my own version of reality, one page at a time, with receipts.

I printed the clerk’s reply. I printed the airline note. I printed my mother’s text about guardianship. I created a timeline with dates and times and agencies. I attached the airport incident slip to the top like a cover page, because it was the simplest proof of a complicated truth: they had tried to trap me, and it had backfired.

By late afternoon, my exhaustion hit like a wave. I lay back on the bed and stared at the ceiling. The room was quiet. The folder was still there. The world outside the window moved like it always did.

I thought about my grandfather, not as a body in a casket, not as an estate file, but as a man who had looked at me once across his kitchen table and said, “People will tell stories about you, Nina. Don’t let them be the only stories in the room.”

I hadn’t understood then. I understood now.

That evening, my mother called. I watched the phone ring until it stopped. She called again. And again. Then she left a voicemail.

Her voice was soft and trembling. “Honey,” she said, “please call me back. We’re worried. This isn’t you. You’re being influenced. We just want to help you.”

I deleted it.

Not because it didn’t hurt. It did. It hurt in the ancient place where children still want their parents to be safe. But I deleted it because I recognized the technique. She wanted to create a record of concern, to counter the record of obstruction. She wanted to seed the next chapter.

I refused to co-author it.

The next morning, Lane called. “They’re already asking for a meeting,” he said.

“With you?” I asked.

“With your counsel,” he corrected. “They want to ‘clear the air.’”

I made a sound that wasn’t quite a laugh. “Clear the air,” I repeated. “After they tried to handcuff me into silence.”

Lane’s tone was dry. “Yes. That’s how people like this operate. When pressure doesn’t work, they try charm.”

“What do we do?” I asked.

“We stay procedural,” he said. “We let the neutral administrator do their work. We prepare for the evidentiary hearing. And we keep documenting. Every contact. Every attempt. Every shift.”

I took a breath. “And if they try guardianship?”

“Then we fight it,” he said, simple. “But we don’t borrow trouble. We respond, we don’t panic.”

After we hung up, I opened my laptop and began writing, not a diary, not an emotional rant, but a statement of facts. Dates. Times. Names. I described the airport stop. The call log. The airline cancellation. The motion. The hearing. The judge’s orders. I wrote it the way you write something you might need later—not to convince someone you’re right, but to prove you were there.

Because that was the core of it, wasn’t it?

They had tried to erase me.

Not just from court. From credibility. From the record. From my own story.

A week later, when I returned for the evidentiary hearing, the air in that courthouse felt different. People recognized my name. Not as a rumor. As a party. As a person with standing. The administrator had already begun inventory. Assets were frozen from impulsive movement. My parents couldn’t just “handle it” anymore.

When my father saw me that day, he didn’t smile. He didn’t greet me like a child. He looked at me like a problem he couldn’t solve with a phone call.

The judge opened the session by reiterating his order: no more games. No more emergency accommodations requested without notice. No more “concern” that turned into obstruction.

Then witnesses were called. The attorney who had drafted the will testified to my grandfather’s lucidity. The witnesses confirmed the signing. The administrator testified to the estate’s status.

And then the CAD printout came up again. A line read into the record. A timestamp. A note.

Not present.

My father’s attorney tried to soften it. “Not present at that moment,” he said. “He arrived later.”

The judge’s gaze stayed steady. “But not present when the call was placed,” he said. “Not present when the decedent requested help.”

My father’s face did something small and sharp—an involuntary flinch. It wasn’t guilt. It was recognition that a neutral system had written down the thing he couldn’t talk his way out of.

When my father took the stand, he tried the same language he’d used at the airport and the airline: concerned, worried, unstable. But the judge stopped him early.

“Mr. Holloway,” the judge said, “this court is not interested in your opinion of your daughter’s stability. This court is interested in facts regarding the decedent’s capacity and the validity of the will.”

My father’s throat bobbed. He glanced at his attorney, then back at the judge. “We just wanted to protect him,” he said.

“Yet you were not present,” the judge replied, and there was no anger in his voice, only the quiet authority of someone who sees the difference between love and control.

The hearing didn’t end with a dramatic slam of a gavel. Real life rarely does. It ended with scheduling, with orders, with the slow machinery of law grinding toward something like fairness. But when it was over, and we stepped back into the hallway, I felt something I hadn’t felt since my grandfather died.

Space.

Not empty space. Breathing space.

Lane walked beside me, and his voice was low. “They’re cornered,” he said. “Not emotionally. Procedurally. That’s the kind that matters.”

My mother passed us without looking at me, her face set like stone. My father stared at a wall as if he could will it to open and swallow him. Their attorney spoke in a hurried whisper, not soothing them, but managing them.

As we left the courthouse, sunlight hit my face and I didn’t squint away. I stood on the steps for a second and felt the weight in my chest shift again—still heavy, still real, but no longer crushing. Grief sat beside it. Anger sat beside it. And something else too, something like respect for myself, earned the hard way.

In the parking lot, my phone buzzed with a new email. Not from my parents. Not from their lawyer.

From the clerk.

A short notice: The court has entered an order confirming neutral administration pending further proceedings. Parties are reminded that any false reporting to law enforcement or interference with court process may be referred for sanctions or additional review.

I read it twice. Then I saved it. Then I backed it up. Then I took a screenshot and saved that too, because I had learned that when you’re dealing with people who rewrite reality, you keep copies.

That night, back in the hotel, I placed the folder on the nightstand again. But this time it didn’t feel like a fragile thing. It felt like a spine. Like proof that I hadn’t imagined any of it. Like something solid in a family that had tried to make me feel like smoke.

I lay down and listened to the quiet. Not the anxious quiet of waiting for the next attack. The ordinary quiet of a room that wasn’t holding its breath.

And for the first time in weeks, I slept all the way through the night.

In the morning, my phone buzzed once. One new message, not from my mother, not from my father.

From Lane.

We’re not done, but you’re no longer alone in the record.

I stared at the text until my eyes blurred a little. Then I set the phone down and looked at the folder.

My parents had tried to erase me with uniforms, cancellations, and motions. They had tried to build a paper version of me that looked unstable enough to dismiss. But paper cuts both ways.

In the end, what stopped them wasn’t my anger or my tears. It wasn’t a dramatic confrontation in an airport or a courtroom scream.

It was the log.

The calm, boring, indifferent log that didn’t care about family loyalty or inheritance or reputation. The log that simply recorded who called, who said what, who was present, who wasn’t. The log that turned their strategy into a timeline and their timeline into proof.

And that was the thing they never understood about me.

Calm isn’t weakness.

Calm is control.

And control—real control—doesn’t come from making people afraid of you.

It comes from making the truth impossible to ignore.

The courthouse emptied the way storms do—suddenly and without ceremony. One moment the hallway was crowded with voices, shoes scraping marble, lawyers murmuring strategy into phones. The next, it was just echoes and the faint smell of old paper and disinfectant. I stood there for a second longer than necessary, my folder tucked against my ribs, listening to my own breathing like I was checking to make sure it was real.

Elliot Lane waited until my parents disappeared around the corner before he spoke. “You should go,” he said gently. “Let today land.”

I nodded, though my body didn’t quite move yet. Winning—if this could even be called that—never felt the way movies promised. There was no rush, no triumph, no swelling music. There was only the quiet understanding that something dangerous had been stopped mid-swing.

Outside, the sky was a hard, unbothered blue. The flag over the courthouse kept snapping in the wind, rhythmic and indifferent, like it had been doing this long before my family learned how to weaponize concern. I walked down the steps slowly, every footfall deliberate, as if rushing might undo the record that had just been written.

In the parking lot, I sat in my car with the engine off and stared at the dashboard. My hands were steady. That surprised me. They hadn’t been steady in weeks. Not at the funeral. Not on the plane. Not when I’d watched my parents try to erase me with official language and borrowed authority. But now they rested easily on the steering wheel, like they trusted me again.

My phone buzzed.

A text from my mother.

We didn’t raise you to do this.

I read it once. Then again. It was such a small sentence for everything it was trying to do. Shame disguised as disappointment. Control disguised as heartbreak. I imagined her typing it carefully, believing it would land like a final blow.

I didn’t respond.

Instead, I turned the key in the ignition and pulled out of the lot, letting the courthouse shrink in the rearview mirror. The road stretched ahead of me, ordinary and unremarkable, and that felt like mercy.

Back at the hotel, I dropped the folder onto the desk and leaned my forehead against the window. The room was quiet in a way that felt earned. I could hear traffic below, the low hum of other lives moving forward without knowing mine had just changed shape.

I finally opened my father’s email.

It was longer than my mother’s text, dense with justification. He wrote about fear, about responsibility, about how the world was dangerous and how I didn’t understand it the way he did. He wrote about my grandfather’s “confusion” and my “distance” and how none of this would have happened if I’d just listened.

He never mentioned the airport report.

He never mentioned the airline call.

He never mentioned the motion that had been denied in open court.

That omission told me everything.

I closed the email and archived it. Not deleted—archived. I had learned the value of records.

That night, sleep came in pieces. Not from fear, but from replay. The judge’s voice. The sound of my father being told to sit down. The moment the CAD log was read into the record and the room changed temperature. Each memory surfaced, passed through me, and settled somewhere quieter than before.

In the morning, there was another message from Elliot Lane.

Neutral administrator confirmed. Assets frozen pending inventory. No emergency motions granted. You’re safe today.

Safe.

The word felt unfamiliar in this context, like a coat that didn’t quite fit yet. But I held onto it anyway.

Over the next few days, the fallout began—not dramatic, not explosive, but precise. Letters arrived. Notices. Requests for documentation. The neutral administrator asked for keys, records, access. My parents’ attorney sent a clipped email acknowledging the court’s orders and requesting that all communication be routed formally.

My parents themselves went quiet.

That silence was louder than any threat.

A week later, I returned to my grandfather’s house with the administrator present. It was the first time I’d been back since the funeral. The air inside smelled faintly of dust and old coffee, the way it always had. Nothing looked different, and that hurt more than if everything had been stripped bare.

The administrator was professional, neutral, careful. She photographed rooms, noted items, cataloged paperwork. She asked me factual questions and wrote down my answers without commentary.

In my grandfather’s study, she paused at the desk. “Did he work here often?” she asked.

“Yes,” I said. “Every day.”

She nodded and wrote it down.

On the desk sat a framed photo of us from years ago, taken long before wills and hearings and police reports. He had his arm around my shoulder, smiling like the world hadn’t yet taught him how family could fracture.

I didn’t touch the frame.

I didn’t have to. The record already knew it belonged there.

That evening, my father called.

I watched the phone ring until it stopped. Then it rang again. Then again. Finally, a voicemail.

This time his voice was tight, stripped of warmth. “You think you’ve won,” he said. “But you’ve made a mistake. You’ve made this public. People don’t forget.”

I listened to the message twice. Not because I needed to, but because I wanted to hear the fear underneath the anger. It was there, faint but unmistakable. He was realizing something he’d never had to face before: that authority doesn’t belong to the loudest voice in the room, and records don’t care who raised you.

I saved the voicemail.

The evidentiary hearing came a month later. By then, the narrative my parents had tried to construct had collapsed under its own weight. Their claims about my grandfather’s incapacity didn’t survive contact with documentation. Their timeline contradicted itself. Their urgency looked less like concern and more like impatience.

When the judge ruled—methodically, carefully, without flourish—it felt less like a victory and more like a correction. The will stood. The neutral administration continued. Certain behaviors were explicitly warned against.

My parents didn’t look at me as the courtroom emptied. They didn’t have to. The distance between us had finally been named, measured, and entered into the record.

Outside, Elliot Lane shook my hand. “This doesn’t fix everything,” he said. “But it fixes what matters legally.”

I nodded. “That’s enough.”

In the weeks that followed, life didn’t magically soften. Family didn’t suddenly become safe. Grief didn’t evaporate just because the law had done its job. But something fundamental had shifted.

I no longer felt like I was arguing with ghosts.

I moved apartments. Changed my phone number. Locked down accounts. Each step was small, unglamorous, but solid. Control rebuilt itself quietly, like muscle memory returning after injury.

One afternoon, months later, I sat in a café scrolling through news on my phone when a headline caught my eye—an article about misuse of emergency reporting systems, about how false concern could become a form of coercion. I read it without flinching.

I knew that story.

I had lived it.

The difference now was that it no longer lived in me the same way.

That night, I took the folder from my closet and laid it on the table. I went through every page one last time—the airport incident slip, the airline notes, the court orders, the CAD log. I scanned them, backed them up, then placed the originals in a fireproof box.

When I closed the lid, I felt something release in my chest.

Not forgiveness.

Finality.

I understood then that my parents would probably never see themselves the way the court had seen them. They would tell a different version of this story to anyone who would listen. In theirs, they were worried. Misunderstood. Pushed too far.

But that no longer mattered.

Because the most important story—the one that counted—had already been written somewhere they couldn’t edit.

In a dispatch log.

In an airline note.

In a court order.

In ink that didn’t care about family titles.

I turned off the light and stood in the dark for a moment, breathing evenly. Calm had stopped being something I performed for survival. It had become something I owned.

And for the first time since the day at airport security, when an officer stepped into my path and tried to turn me into a problem, I felt something like peace—not because the world was fair, but because the truth had held.

Calm isn’t weakness.

Calm is leverage.

And once you understand that, no one can erase you again.

The courthouse didn’t explode into chaos after the ruling. It didn’t gasp or whisper or lean forward like people do in movies. It simply absorbed the decision and moved on, the way institutions always do. Chairs scraped. Papers were gathered. Voices dropped back into procedural tones. What had just happened to my family was monumental to me, devastating to my parents, and barely a ripple to the building itself.

That contrast stayed with me as I followed Elliot Lane down the hallway. My legs felt solid beneath me, but there was a strange hollow pressure behind my sternum, like my body hadn’t yet decided whether to exhale or brace for another blow.

“You did well,” Lane said again, not looking at me, his eyes forward. “Especially when he tried to bait you.”

I nodded. Talking felt unnecessary. Words had been used enough for one lifetime.

We reached the exit doors, the heavy glass swinging open with a hydraulic sigh. Outside, the afternoon light was too bright, too normal. A couple argued quietly near the steps. A woman balanced a coffee and a phone while juggling her keys. Someone laughed. Life hadn’t paused for my family’s implosion, and that almost hurt more than if it had.

Lane stopped. “I’ll be in touch,” he said. “Next steps will come in writing.”

“Thank you,” I replied. It sounded thin, but it was honest.

He gave me a nod that was half professional, half human, then turned back toward the building. I stood there for a moment, my folder pressed against my side, watching him disappear into the crowd of suits and briefcases. Then I walked down the steps alone.

My parents were nowhere in sight.

That shouldn’t have surprised me. Confrontation was only useful to them when they controlled the narrative. Now that the record had slipped from their hands, retreat was the smarter move. Still, the absence felt sharp, like the afterimage of a punch you’d braced for that never came.

I sat in my car and rested my forehead against the steering wheel. I didn’t cry. I waited for tears, but they didn’t come. What came instead was exhaustion so deep it felt cellular. Every muscle in my body hummed with it, a low-frequency ache earned over months of vigilance.

When I finally drove away, I didn’t go straight back to the hotel. I drove aimlessly, letting the roads unspool beneath me. Strip malls. Gas stations. Familiar American nothingness. Each red light gave me time to breathe. Each green light reminded me that momentum still existed.

At the hotel, I kicked off my shoes and sat on the edge of the bed, folder still in my hands like I was afraid it might disappear if I let go. I set it down slowly, deliberately, and waited for the room to feel unsafe without it.

It didn’t.

That realization startled me more than anything else that day.

I checked my phone. No new messages from my parents. No missed calls. The silence was deliberate now, not tactical. They were regrouping, rewriting, deciding which version of themselves they would present to the world next.

I opened my laptop and began documenting.

Not because anyone had asked me to. Because I had learned the cost of not doing it sooner.

I wrote the timeline from memory first, then cross-checked it against the papers. Airport security stop. Call log pulled. Caller identified. Airline cancellation. Hearing moved. Motion denied. Neutral administrator appointed. Each entry had a date, a time, a source. I kept the language dry, factual, almost boring. Emotion belonged in private. Documentation belonged in neutral.

When I finished, I saved the file in three places.

Only then did I let myself lie back and stare at the ceiling.

That night, I dreamed of my grandfather—not as he’d been at the end, frail and fading, but as he’d been when I was younger. He sat at his kitchen table with a mug of coffee, papers spread out in front of him, humming to himself while he read. He didn’t look up at me. He didn’t need to. The dream wasn’t about reassurance. It was about continuity.

I woke before dawn, the room still dark. For a moment, panic flared—an old reflex—before my body remembered where it was. The danger had passed. Not disappeared. Passed.

I made coffee I barely drank and sat by the window as the city woke up. My phone buzzed around eight.

A text from my mother.

We need to talk.

No apology. No acknowledgment. Just an assumption of access.

I stared at the words until the screen dimmed. Then I locked the phone and set it face down.

I didn’t need to talk.

What she wanted wasn’t conversation. It was recalibration. She wanted to pull me back into orbit, to find the tone that would work now that fear and urgency had failed. I recognized the pattern. I had lived inside it my entire life.

By midmorning, Elliot Lane emailed. A clean, professional message summarizing the court’s orders and outlining the next procedural steps. Neutral administration would proceed. Assets would be inventoried. No unilateral actions permitted. Any contact from my parents that could be construed as interference should be documented.

I forwarded the email to myself and archived it.

That afternoon, I returned to my grandfather’s house with the administrator again. This time, the house felt different. Not haunted. Paused. Like a space waiting for its next purpose.

We worked through closets and drawers. The administrator asked questions. I answered them. When we reached the garage, she paused at a stack of old boxes.

“These weren’t listed,” she said.

“They’re personal,” I replied. “Old records.”

She nodded. “As long as they’re not financial, they’re yours.”

I opened one box and found letters—handwritten, yellowed, tied with string. Not love letters. Correspondence. Notes between my grandfather and his attorney over the years. Careful, deliberate, thoughtful. Evidence of a man who took his decisions seriously.

I swallowed.

The administrator watched me quietly. “Take your time,” she said.

I closed the box. “I will.”

That evening, my father emailed again.

This one was colder.

You’ve crossed a line. Family matters shouldn’t be handled like this.

I almost laughed. Almost.

Family matters, to him, had always meant matters he controlled. When control slipped, he called it betrayal.

I didn’t reply.

Over the next few weeks, the shape of my life began to change in small, almost invisible ways. I rerouted mail. Updated passwords. Removed emergency contacts. Each administrative task felt strangely empowering. Not dramatic. Just necessary.

Friends reached out—some cautiously, some bluntly. A few had heard whispers. A few had heard nothing. I told the truth when asked, without embellishment. I didn’t need their validation. I needed my own consistency.

My parents tried again, this time through extended family. An aunt called, voice heavy with concern, asking why things had “gotten so out of hand.” I listened. I thanked her for caring. I said only, “There are court orders in place, and I’m following them.”

She didn’t push. She didn’t need to. The phrase court orders did what arguments never could.

One night, months later, I received a notification from an unfamiliar number. A voicemail.

It was my father.

His voice sounded older. Not softer. Just thinner.

“They’re asking questions,” he said. “About the airport call. About the airline. This didn’t need to happen.”

I listened twice.

He wasn’t angry anymore. He was scared.

I saved the voicemail.

Because fear, unlike anger, tells the truth.

The inquiry didn’t move fast. These things never do. But it existed, and that alone mattered. My parents had spent their lives believing systems bent for people like them. Now they were discovering that systems remember.

In the quiet stretches between legal updates, grief finally caught up to me. Real grief. Not the performative kind that gets you sympathy. The kind that arrives late and sits heavy.

I missed my grandfather in ways that surprised me. I missed his silence. His steadiness. The way he listened without trying to manage the outcome.

One afternoon, I sat in his empty study with the door closed and let myself cry. Not about the inheritance. Not about my parents. About the simple fact that he wasn’t there to see this, to know that when it mattered, I hadn’t folded.

That night, I dreamed again. This time he looked up at me. He didn’t smile. He just nodded.

I woke up feeling lighter.

The final hearing came almost a year later. By then, the sharp edges had dulled. The facts stood where they stood. The will was upheld. The administration concluded. My share transferred cleanly, without drama.

My parents attended, quieter now, diminished. They didn’t speak to me. They didn’t need to. The space between us had hardened into something permanent.

When the judge closed the case, there was no lecture this time. Just procedure. Just finality.

Outside, I stood alone on the courthouse steps again. Same building. Different version of me.

I realized then that what had changed most wasn’t my circumstances. It was my internal posture. I no longer waited for permission to exist in rooms where decisions were made.

That night, I took the folder—the one that had traveled with me through airports and courtrooms—and emptied it. I scanned everything one last time, labeled it, stored it. Then I slid the empty folder into a drawer.

It had done its job.

Weeks later, I ran into someone at a grocery store who knew my parents. She looked at me with curiosity, maybe even pity. “I heard things were… difficult,” she said.

I smiled politely. “They were.”

She waited for more.

I didn’t give it to her.

Because the story was no longer public property.

It was mine.

Sometimes, late at night, I still think about that moment at airport security—the officer stepping into my path, the quiet authority in his voice, the way my name sounded when it was treated like a problem.

I think about how close I came to being erased with paperwork and tone.

And then I think about the log.

The boring, unfeeling, indispensable log.

The thing that didn’t care who loved whom, who raised whom, who paid for what. The thing that simply recorded what happened.

In the end, that was enough.

Calm didn’t save me because it made me agreeable.

Calm saved me because it kept me precise.

And precision—paired with truth—is something even family can’t overpower.

Not forever.

Not when the record is sealed.

Not when you’re still standing.

News

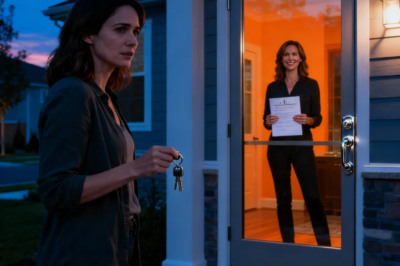

PACK YOUR THINGS. YOUR BROTHER AND HIS WIFE ARE MOVING IN TOMORROW,” MOM ANNOUNCED AT MY OWN FRONT DOOR. I STARED. “INTO THE HOUSE I’VE OWNED FOR 10 YEARS?” DAD LAUGHED. “YOU DON’T ‘OWN’ THE FAMILY HOME.” I PULLED OUT MY PHONE AND CALLED MY LAWYER. WHEN HE ARRIVED WITH THE SHERIFF 20 MINUTES LATER… THEY WENT SILENT.

The first thing I saw was the orange U-Haul idling at my curb like it already belonged there, exhaust fogging…

MY CIA FATHER CALLED AT 3 AM. “ARE YOU HOME?” “YES, SLEEPING. WHAT’S WRONG?” “LOCK EVERY DOOR. TURN OFF ALL LIGHTS. TAKE YOUR SON TO THE GUEST ROOM. NOW.” “YOU’RE SCARING ME -” “DO IT! DON’T LET YOUR WIFE KNOW ANYTHING!” I GRABBED MY SON AND RAN DOWNSTAIRS. THROUGH THE GUEST ROOM WINDOW, I SAW SOMETHING HORRIFYING…

The first thing I saw was the reflection of my own face in the guest-room window—pale, unshaven, eyes wide—floating over…

I came home and my KEY wouldn’t turn. New LOCKS. My things still inside. My sister stood there with a COURT ORDER, smiling. She said: “You can’t come in. Not anymore.” I didn’t scream. I called my lawyer and showed up in COURT. When the judge asked for “proof,” I hit PLAY on her VOICEMAIL. HER WORDS TURNED ON HER.

The lock was so new it looked like it still remembered the hardware store. When my key wouldn’t turn, my…

At my oath ceremony, my father announced, “Time for the truth-we adopted you for the tax break. You were never part of this family.” My sister smiled. My mother stayed silent. I didn’t cry. I stood up, smiled, and said that actually I… My parents went pale.

The oath was barely over when my father grabbed the microphone—and turned my entire childhood into a punchline. We were…

DECIDED TO SURPRISE MY HUSBAND DURING HIS FISHING TRIP. BUT WHEN I ARRIVED, HE AND HIS GROUP OF FRIENDS WERE PARTYING WITH THEIR MISTRESSES IN AN ABANDONED CABIN. I TOOK ACTION SECRETLY… NOT ONLY SURPRISING THEM BUT ALSO SHOCKING THEIR WIVES.

The cabin window was so cold it burned my forehead—like Michigan itself had decided to brand me with the truth….

AFTER MY CAR ACCIDENT, MOM REFUSED TO TAKE MY 6-WEEK-OLD BABY. “YOUR SISTER NEVER HAS THESE EMERGENCIES.” SHE HAD A CARIBBEAN CRUISE. I HIRED CARE FROM MY HOSPITAL BED, STOPPED THE $4,500/MONTH FOR 9 YEARS-$486,000. HOURS LATER, GRANDPA WALKED IN AND SAID…

The first thing I saw when I woke up was the ceiling tile above my bed—white, speckled, perfectly still—while everything…

End of content

No more pages to load