The first thing I noticed was his badge.

Not the name—those are always printed in the same bland font HR uses to make everyone look equally replaceable. It was the plastic shine, still too clean, still too stiff, clipped to the pocket of a suit that hadn’t yet learned the building’s temperature. He’d been in the office less than three hours. People were still doing that polite American thing where they compliment a handshake like it’s a leadership skill.

And at 9:07 a.m., with the welcome badge still hanging there like proof he hadn’t earned anything yet, he leaned back in the chair across from my desk, tapped a neat stack of reports with two fingers, and said, almost conversationally, “These are redundant.”

Not wrong. Not inefficient. Not outdated. Redundant.

The word didn’t hurt because it was insulting. It hurt because of how casually he dropped it, like he was pointing out a duplicate stapler. Like the last three years of my quiet work—three years of late-night reconciliations, vendor escalations, spreadsheet autopsies, and manual checks that prevented us from bleeding money—were just my personal preference. A hobby I refused to give up.

I didn’t push back right away.

In corporate finance, you don’t survive by arguing with a new executive who arrived with a transformation agenda and a head full of buzzwords. You survive by watching. By listening. By measuring the distance between their confidence and their comprehension.

With him, the gap was wide.

His résumé was expensive. People said that about executives the way they say a car is expensive—like the cost itself is proof of value. He’d done big projects at big companies with big logos. He had the rhetoric too: “efficiency,” “streamlining,” “single source of truth,” “eliminating friction.” The kind of language that makes people nod because it sounds like progress even when it’s just air.

He didn’t have context.

Most people didn’t, because most people didn’t know what my job actually was. They thought I checked invoices. That’s what HR wrote years ago in a description they probably copy-pasted from a template: Accounts Payable Analyst, vendor support, invoice review, basic reconciliation.

Basic.

What I actually did was find the errors the vendor insisted did not exist.

Mismatched purchase orders. Duplicate line items hidden in batch totals. Discounts applied twice, then reversed incorrectly, then reapplied in a later cycle. Taxes calculated with the wrong table because someone on their side had toggled a setting and forgotten. Accidental zeros added by someone half-trained or half-asleep, turning a $1,250 adjustment into $12,500 and hoping no one noticed because the rest of the batch was huge.

Over time, the vendor’s team started treating my corrections as part of the “natural workflow.” They’d send sloppy batches. I’d clean them. The system would balance. Nobody asked questions except me.

And for months—quietly, professionally, in writing—I’d been warning my old director that the vendor integration wasn’t as automated as they kept claiming. Errors weren’t decreasing; they were shifting. The obvious mistakes disappeared. The subtle ones grew teeth.

Somewhere on the vendor side, someone had learned that if you bury a bad adjustment inside a high-volume cycle, it slides through unless someone manually cross-reconciles it against internal ledgers. Unless someone does what I did.

That someone was me.

But now, according to the man with the crisp badge and the louder confidence, that work was redundant.

He reached for one of my audit notebooks—the thick spiral-bound one I’d spent two weeks compiling, not for fun, but because I’d learned the hard way that a warning without documentation is just a complaint. The notebook had tabs. Dates. Screenshots. Ticket numbers. Anomaly patterns. Vendor responses. My own notes in the margins like scars.

He skimmed two pages. Closed it. Handed it back with a polite nod, like he’d just flipped through a menu.

“Good work,” he said. “But we don’t need this level of granularity. The vendor should handle their own errors.”

I didn’t answer, not because I agreed, but because I wanted to hear the rest. Silence makes executives reveal more than arguing does. He mistook my silence for compliance.

“Let’s sunset these,” he added, tapping the folder. “If the vendor wants accountability, they can provide it. We don’t need internal double checks. It slows things down.”

There it was. The phrase every seasoned analyst recognizes.

Slows things down.

Translation: I don’t understand this system, but I want it simpler so I can feel in control.

I asked one question, because it was the only one that mattered.

“Do you want me to stop the reconciliations immediately,” I said, “or finish this cycle first?”

He didn’t hesitate.

“Immediately,” he replied. “I’ll take responsibility for the transition.”

That last line wasn’t confidence. It was arrogance disguised as ownership. But it was also exactly what I needed.

I opened a blank memo template, typed a clean summary of his directive while he stood there, and printed it. I didn’t write it emotionally. I didn’t write it dramatically. I wrote it like a process change: effective immediately, reconciliation workflow discontinued at COO direction, vendor will own all upstream accuracy and internal double-checks will be removed to improve cycle speed.

I handed it to him. He scanned for keywords the way executives do when they think reading is beneath them, signed without reading the whole thing, and walked away.

The room didn’t feel hostile. It felt strangely calm.

I’d been preparing for something like this for months. Not because I wanted it, but because I knew someone ambitious would eventually get seduced by the vendor’s automation pitch. Someone would look at our reconciliations and think, Why are we doing this? Why are we paying someone to double-check what the vendor promised to automate? Someone would decide they could “modernize” the process by removing the human friction.

Someone would say redundant.

I saved the signed memo. Time-stamped the file. Uploaded it into the internal system where it couldn’t be “lost.” Then I removed myself from the reconciliation workflow exactly the way he requested.

No backdoor checks. No silent fixes. No last-minute catches.

I did exactly what he asked.

That afternoon felt empty, not in a sad way, but in a quiet, anticipatory way—the silence before a storm that only you can smell in the air.

Because nobody tells new executives this:

You can ignore a process. You can ignore a person. You can ignore a warning.

But financial systems don’t ignore anything.

They remember.

By the next morning, the first discrepancy appeared.

And that was only the beginning.

It showed up at 8:42 a.m., small enough to look harmless. The kind of mistake that wouldn’t trigger a dashboard alert. The kind you only notice if you’ve lived inside the system long enough to feel when it breathes differently.

I was doing my best to stay in my lane—reviewing tickets in the shared queue, answering routine questions, keeping my hands off the workflow I’d been removed from—when I noticed a tiny shift in a vendor batch summary. A value that should have been 0.8 suddenly wasn’t.

Not enough to cause panic. Just enough to tell me something upstream had changed.

I didn’t say a word.

The COO wanted the vendor to “own” their numbers. So I let them.

By noon, five more discrepancies appeared. All small. All predictable. Without my reconciliations, the system didn’t explode instantly. It drifted. Quietly. The same direction every time—the direction I’d been manually correcting for months.

At 2:17 p.m., my former director—the one who’d actually listened when I flagged issues—walked to my desk.

He didn’t sit. He didn’t smile. He didn’t even bother with the small talk people use to pretend everything is fine.

“You didn’t touch any of the batches today, right?” he asked.

“No,” I said. “COO’s directive.”

He nodded slowly, the way someone nods when a fear they’ve lived with finally proves itself real.

“All right,” he said. “Keep it that way.”

He walked away before I could ask anything else, because he didn’t need to explain. He knew what the drift meant. He’d seen my notebooks. He’d read my emails. He’d watched the vendor smile and say automation while I quietly held the machinery together.

But that wasn’t the moment everything turned.

That moment came two hours later.

At 4:28 p.m., I heard Michelle’s voice echo from the COO’s office.

Michelle was the vendor manager—calm, polished, professional. She’d been our vendor-facing contact for years. She was good at what she did, which meant she was good at saying no without sounding like she was saying no.

“No,” she was saying now, voice tight around the edges, “that adjustment didn’t come from us. Our numbers were clean on our end.”

A pause. Then Michelle again, still calm, still controlled.

“If they changed internally,” she said, “your team needs to check the workflow.”

It wasn’t anger in her voice. It was confusion. The kind people feel when a system that hasn’t visibly broken in years suddenly slips on basic arithmetic.

I stayed out of it. Completely.

But inside, irritation built—not because the system was drifting, but because everyone acted surprised. They’d been warned. Quietly. Repeatedly. Professionally.

Every anomaly. Every inconsistency. Every flagged correction. I documented them all. I submitted them. I escalated them when necessary. I wasn’t dramatic about it. I wasn’t emotional about it. I was thorough.

And the new COO had dismissed the entire structure in one morning because it “slowed things down.”

At 5:03 p.m., he finally came to my desk.

He didn’t apologize. He didn’t acknowledge the signed directive. He didn’t say my name like he’d been wrong.

He simply asked the question executives ask when they realize complexity might be real.

“Did anything unusual happen in yesterday’s cycle?” he asked.

I looked him in the eye.

“You asked me to stop reconciling,” I said. “So I stopped. That’s the only change.”

He held my gaze a second too long, not angrily—analytically, like he was trying to decide whether I was being passive-aggressive or simply stating a fact.

Then came the next question, the one that told me everything.

“Can you take a quick look at this batch?” he asked. “Just a quick one. Off the record.”

There it was.

The first crack in his confidence. The first attempt to make his decision reversible without admitting it was wrong.

I shook my head.

“I can’t,” I said calmly. “Not without reversing your directive. You said the vendor owns their numbers now.”

His jaw tightened. Not because I refused. Because I reminded him of his own words.

“I’ll handle it,” he muttered, and walked away.

That night, for the first time in three years, I left the building on time.

No late checks. No quiet corrections. No saving the system from itself.

As I walked to my car, the thought hit me—not dramatic, not vengeful, just brutally honest:

They weren’t prepared for what I’d been protecting them from.

By the next morning, the discrepancies wouldn’t be small anymore. And I didn’t fully know it yet, but this was the day everything would start sliding out of their hands fast.

By the third morning, the system wasn’t drifting anymore.

It was slipping.

Not loudly. Not like a movie. Just enough to make everyone uncomfortable without knowing why.

At 9:14 a.m., an alert popped in the finance channel—the kind we almost never saw:

Batch 47 requires secondary validation.

Secondary validation wasn’t a real requirement. It was a placeholder flag. A silent alarm built years ago by an engineer who probably never imagined anyone would rely on it. It only triggered when the numbers coming from the vendor contradicted the internal ledger by more than a safe margin.

A margin I used to correct manually.

I wasn’t part of that workflow anymore. So the flag stayed red.

Two minutes later, another alert.

Then another.

A chain reaction. Small errors colliding with slightly bigger ones, all feeding into the same quarter-end expense cycle like a river finding every crack in a dam.

Finance analysts started pinging each other. Procurement asked if someone had updated the discount matrix. AP blamed a system timing issue. Accounting wanted to know why tax tables weren’t matching.

Nobody blamed the vendor.

Not yet.

At 9:31 a.m., I heard the first sound that told me the COO was starting to panic: his office door closing.

Executives don’t close doors unless something’s wrong. They love transparency when everything is under control. They love open doors when they’re confident. Closed doors are fear.

Inside, voices rose—not shouting, but tight. Controlled voices trying to stay controlled.

Michelle repeated the same phrase over and over.

“Our records don’t show these changes.”

Not defensive. Just factual.

And something inside me shifted. Not anger. Not vindication.

Realization.

For months, I had been patching leaks quietly, automatically, without asking permission. I’d told myself I was protecting the team. Protecting the company. Keeping the system running the way it should.

It took exactly two days without my fixes for me to see the truth clearly.

I hadn’t been protecting them.

I’d been enabling them.

The vendor wasn’t improving because I never forced them to. Leadership didn’t see the risk because I absorbed it. The system never broke because I held it together with invisible stitches.

Now the stitches were gone.

At 10:12 a.m., the COO stepped out of his office, shoulders stiff, face tight, pretending nothing was wrong. But if you’ve been in corporate long enough, you can recognize the expression of someone who just learned something expensive.

He walked straight toward me.

“Can you explain why the discount reconciliation is out of range?” he asked.

Not, Can you help me understand? Not, We’re seeing an anomaly.

A direct question with an accusation tucked inside it like a blade.

I answered plainly.

“I didn’t touch the cycle,” I said. “Per your directive.”

He swallowed that hard. I watched the moment his pride fought his panic.

Then he tried again.

“Look,” he said, voice lower, “can you walk me through what you used to do? Just high level.”

I did.

No embellishment. No bitterness. Just the truth. Step by step: what we compared, where the vendor’s system cut corners, how the internal ledger required real oversight, how automation didn’t replace human checks because the vendor’s data wasn’t clean enough to trust.

By the time I finished, he wasn’t angry.

He was pale.

Because while he’d been cutting “redundant” processes, the discrepancies had been accumulating.

At 11:03, procurement discovered a $142,000 adjustment that shouldn’t exist.

At 11:17, accounting flagged mismatched tax tables.

At 11:26, AP found duplicated payments—small ones, scattered, but too consistent to dismiss as random error.

Every issue led to another. Every audit trail had gaps. Every automated fix the vendor claimed to handle wasn’t fixing anything.

The COO tried to hold it together, but his voice tightened each time someone approached him with a new problem.

I watched him pace between offices, phone pressed to his ear, hand on his forehead like he could push the numbers back into place through force of will.

But numbers don’t negotiate. Mistakes don’t stay small when they stack.

By 12:40 p.m., three departments were involved.

By 1:10 p.m., finance escalated to a cross-functional review.

By 1:35 p.m., the COO had to admit—at least internally—that something was wrong at a system level.

And that was when the crack inside me widened into something bigger. Not directed at him. Not even at the company.

At myself.

For the first time, I wasn’t shocked by the chaos. I wasn’t rushing to fix it. I wasn’t even frustrated.

I was seeing the deeper truth.

Systems reveal character.

His character relied on simplification. Mine relied on responsibility. The vendor’s character relied on someone else catching their mistakes.

Without me, all three were exposed.

At 2:02 p.m., the COO sent a message in the team channel:

We need full documentation on previous reconciliation processes immediately.

He didn’t tag me. Tagging me would mean admitting I’d been right. But it didn’t matter anymore. Not really.

Because when I opened the day’s final batch, I saw something I hadn’t expected to see so clearly.

Not just a mistake. Not just drift.

A pattern.

A deliberate pattern.

Someone somewhere inside the vendor’s workflow wasn’t making random errors. The adjustments were too coordinated. The rounding was too consistent. The misapplied discounts weren’t scattered; they trended in one direction.

It wasn’t proof of anything criminal on its own—patterns aren’t verdicts—but it was enough to make my stomach go cold.

By the fourth morning, the system wasn’t slipping anymore.

It was breaking.

Not all at once. Breakages never happen as one dramatic explosion. They happen as a sequence. One failure feeding another. One minor anomaly becoming structural.

At 8:07 a.m., procurement flagged a $312,000 discrepancy.

At 8:19, AP found a batch rerouted to a shadow cost center.

At 8:26, accounting discovered invoices pushed through without matching purchase orders.

These weren’t random mistakes. They were coordinated enough to suggest something worse than sloppy work.

You don’t see that unless you’ve spent months tracing invisible seams. You don’t recognize how someone hides large adjustments inside high-volume days unless you’ve caught their fingerprints before.

The COO hadn’t. Neither had anyone he trusted.

At 8:42 a.m., he called an emergency meeting.

He didn’t invite me.

He didn’t have to. The walls in that glass-walled conference room weren’t soundproof, and panic carries.

Michelle was the first to speak.

“Your internal checks should have flagged this,” she said, not realizing the irony.

The COO’s answer came sharp, defensive.

“We removed redundant processes based on your automation roadmap.”

Michelle didn’t blink.

“Our automation never replaced manual reconciliation,” she said. “We’ve said that in every quarterly review.”

Silence.

Heavy, ugly silence.

Because there it was: the truth he didn’t want.

He had cut the only layer keeping the system intact, based on a story he wanted to believe.

At 9:14 a.m., everything snapped.

I heard the notification before I saw the screen: a full system freeze warning. Not a yellow flag. Not a soft alert.

A stop-the-line red banner across the finance dashboard:

CRITICAL EXCEPTION: Vendor adjustments exceed threshold.

Threshold wasn’t a suggestion. It was a fail-safe built years ago to catch mass manipulation—situations where the system detects cumulative adjustments beyond a safe limit and shuts down to prevent final processing.

I opened the logs and felt the truth hit me like a fist.

This wasn’t just sloppiness.

This looked like months of manual adjustments stacking on top of each other, hidden in high-volume cycles, relying on the fact that someone—me—would smooth them out before they were visible.

Adjustments I had unknowingly cleaned every month because my job had become absorbing risk the company refused to see.

Now, without my reconciliations, they stacked raw. Layer after layer until the system could no longer pretend.

At 9:22, the COO stormed out of the conference room and came straight to my desk.

No greeting. No pretense.

“I need you in the review room now,” he said.

I didn’t move.

“You removed me from that process,” I said calmly. “You signed the memo.”

He closed his eyes for a second. Not anger. Dread.

“This isn’t the time for blame,” he said.

“It’s not blame,” I replied. “It’s documentation.”

For a moment I thought he’d explode. But he didn’t. He swallowed hard, pride collapsing into necessity.

“Please,” he said.

It wasn’t an apology. But it was the closest he could manage. We were past the point of quick fixes and ego posturing.

So I stood up and followed him.

Inside the review room, the atmosphere was electric with panic. Procurement, accounting, AP, finance analysts—everyone crowded around the screen like it could answer prayers.

Michelle was scrolling through error logs with hands that finally looked less polished.

Then she said the words that changed the temperature of the room:

“This isn’t a glitch,” she said. “These are manual adjustments. Not automated. Not accidental. Manual.”

The COO leaned over her shoulder.

“From your side or ours?” he asked.

Michelle didn’t defend her team reflexively. She didn’t raise her voice. She clicked one button.

Audit trail filter.

A list populated instantly—usernames, timestamps, adjustment codes, notes, all the fingerprints you can’t erase inside a properly logged system.

Every single adjustment that triggered the freeze traced back to one vendor employee account.

I recognized the username.

Six months ago, I’d flagged patterns under that same name: suspicious rounding, repeated discount misapplications staged as “fat finger” errors, always trending upward. I’d warned my old director. He’d documented the warning. The new COO had never read that file.

Michelle’s voice went quieter.

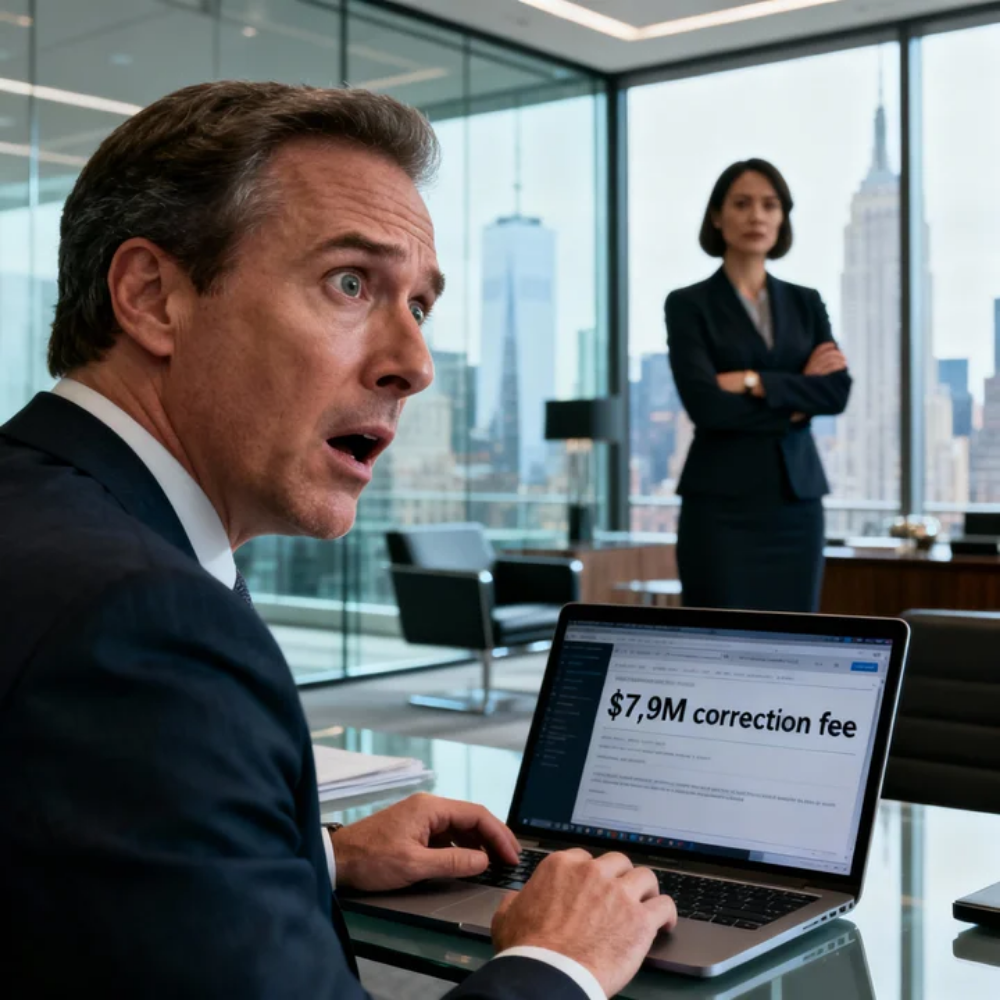

“If these adjustments hit final processing,” she said, “the correction fee on our side could be substantial.”

“How substantial?” the COO asked.

Michelle typed into a calculator, fed it the number of impacted batches, the contractual correction formula, and the escalation multipliers.

The room went dead still.

“Seven point nine million,” she said.

Nobody breathed.

Because now it wasn’t about efficiency. It wasn’t about workflow speed. It wasn’t even about who was embarrassed.

It was about liability. Contracts. Exposure. Whether the company would have to report an unexpected hit, whether finance would have to explain it, whether leadership would have to answer to the board.

The COO finally turned to me. His face was pale. Sweat stood at his hairline.

“What do we do?” he asked.

Not Can you fix this?

Just the raw question of a man standing on unstable ground.

Something inside me settled into clarity.

“We don’t do anything yet,” I said. “We document. Every step, every signature, every directive, every recommendation. You’ll need it for escalation.”

His eyes flicked like he didn’t want to hear the next part.

“Escalation to who?” he asked.

I looked at the screen, at the red warning banner, at the seven-figure liability projection glowing like a siren.

“To legal,” I said. “To finance leadership. To the vendor’s compliance team.”

Then, because avoiding the truth would only make it worse, I added the final line:

“And to the board.”

The weight landed on him so hard he actually sat down.

The system was broken. The pattern was exposed. The damage was real.

And the avalanche he’d started with one word—redundant—was finally coming back down the mountain.

The board meeting wasn’t dramatic.

Corporate myths love to paint these moments as shouting matches, people pointing fingers, executives sweating through their suits while someone slams a fist on a table.

Reality is quieter, sharper, and more dangerous.

By the time the COO presented the escalation packet—documentation, audit logs, vendor trail, legal analysis, the liability estimate—the board already had the numbers. You don’t surprise a board with eight-figure exposure. Someone briefs them in advance. Someone sends summaries. Someone prepares talking points.

I wasn’t in the boardroom. I wasn’t supposed to be.

But you don’t have to be physically present to understand how those conversations unfold if you’ve watched enough leadership rooms from the outside.

A leader makes a sweeping decision. Cuts a process he doesn’t understand. Dismisses expertise he didn’t bother to evaluate.

Then the system collapses, and he learns the most expensive lesson in governance:

Authority without comprehension is negligence.

The meeting lasted forty-six minutes. Not long, not short—just long enough to walk through the audit trail one document at a time.

Including the memo.

My memo.

The one he signed. With his signature, his timestamp, and the line that mattered: effective immediately, reconciliation discontinued per COO directive.

Every consequence flowed from that.

At 11:58 a.m., he stepped out of the boardroom looking like a man who’d aged ten years in under an hour. His tie was slightly crooked—not dramatic, just enough to show his mind had been somewhere else.

He walked into the review room where Michelle, my old director, and a few others were gathered. I stayed at my desk, not because I was hiding, but because I respected the process. This wasn’t my moment.

It was his.

He looked around the room, drew a breath, and said something I didn’t expect—because executives rarely say it, even when it’s true.

“This one’s on me,” he said.

No excuses. No deflection. Just the sentence.

Then he added, quieter, “And I should have listened.”

He didn’t say it to me directly. He didn’t have to. The words mattered less than the fact that he’d learned the weight of what he’d dismissed.

But the consequences didn’t stop at an admission.

Half an hour later, legal sent a notification:

Effective immediately, vendor operations are suspended. Formal review initiated.

Eight minutes after that, the vendor was notified of preliminary correction assessment.

The vendor’s compliance team called Michelle in a kind of panic that tries to stay professional. Their senior director flew in the next morning.

Their internal logs confirmed what our audit trail suggested: one employee had been making repeated manual adjustments over months, hiding them inside large cycles, relying on the fact that internal reconciliations would smooth the impact before it triggered alarms.

He was terminated within twenty-four hours.

The vendor absorbed the fee without argument. They couldn’t afford to fight it. The documentation was airtight.

Within days, the narrative shifted from “system glitch” to “internal vendor control failure.” Nobody in corporate wants to say the word “fraud” without legal counsel, so they didn’t. They said “unauthorized activity.” “Control breach.” “noncompliance with adjustment protocols.”

But everyone in the room understood what those phrases meant.

As for the COO, the board didn’t fire him.

Corporate rarely fires a high-level executive over one mistake, even an expensive one. It spooks investors. Creates instability. Invites scrutiny. It makes headlines. And boards hate headlines more than they hate incompetence.

What they did was worse and far more realistic.

They stripped him of operational authority and moved him into a “strategic” role—a title with no power, no influence, and no real responsibilities. The kind of role companies create when they want someone to stay quietly until they decide to leave on their own.

He wasn’t a villain. He wasn’t a monster.

He was a man who believed confidence could replace comprehension.

In corporate systems, that belief costs millions.

At 3:00 p.m., when the dust finally settled, my old director walked over and set a folder on my desk.

“You kept this place together longer than anyone knew,” he said. “They see that now.”

Inside the folder was a revised job description.

My job restored, upgraded, rewritten with accuracy it should have had years ago. A new title. A raise. Formal authority over vendor reconciliation oversight, process controls, and escalation protocols.

Not because they were rewarding me.

Because they finally understood the value of what they almost removed.

For the first time since all of this began, I felt something strange.

Not vindication. Not pride. Not the sweetness of revenge people fantasize about when they’re exhausted.

Peace.

Because the truth is, I didn’t want chaos. I didn’t want him humiliated. I didn’t want to watch the company burn.

All I ever wanted was for someone to listen when the numbers told a story.

Numbers always tell the truth.

That evening, as I shut down my computer and walked toward the elevator, I opened the memo he’d signed on day one.

Vendor owns their numbers.

I saved it again—not as leverage, not as evidence, not as a weapon.

As a reminder.

Systems don’t break suddenly. People break them slowly: ego, shortcuts, the belief that experience is optional.

But someone always sees the cracks.

And if that person steps away—even for one cycle—everything that happens after isn’t a fight.

It’s repayment.

And in this case, repayment came with a price tag the building would remember long after the welcome badge was thrown away.

I wish I could say the ending was clean.

Corporate endings rarely are.

There was no applause. No standing ovation. No company-wide email calling me a hero. That’s not how American workplaces reward the people who keep disasters from happening. They don’t like admitting how close they came to failure, and they don’t like spotlighting someone who proves the system was fragile.

Instead, the company did what companies do: they patched the narrative. They framed the incident as a “vendor anomaly” that was “swiftly resolved.” They praised leadership for “decisive action.” They held a meeting about “lessons learned” where everyone nodded and pretended the lesson wasn’t painfully obvious.

And quietly, in the background, they corrected processes they had ignored for years.

They rebuilt the reconciliation layer—this time with formal support, clearer controls, and actual visibility so it didn’t depend on one person’s invisible effort.

They renegotiated vendor terms. They implemented better monitoring. They updated audit triggers. They gave procurement and AP new escalation guidelines.

They did all the things I’d been asking for, for months, before a new executive decided my work was redundant.

And me?

I walked into my apartment that night—small, quiet, ordinary—and sat on the edge of my couch without turning on the TV. My brain was still buzzing with numbers, timestamps, voices behind closed doors, that red banner screaming critical exception.

In the silence, I realized something I hadn’t allowed myself to admit before.

For years, I’d built my identity around being the person who caught problems quietly. The person who fixed things without being asked. The person who kept the machine running.

I told myself it was loyalty.

It was competence.

It was professionalism.

But part of it was fear.

Fear that if I didn’t hold everything together, everything would fall apart and I would be blamed anyway. Fear that if I stopped doing invisible work, people would realize they had been relying on me without acknowledging it, and then they’d resent me for it.

When the new COO cut my process, it wasn’t just a professional insult.

It was a forced experiment.

It proved something I needed to know:

A system that only works when one person silently absorbs all the risk is not a good system.

It’s a fragile system with a quiet hero complex built into it.

And quiet heroes burn out.

That’s what almost happened to me.

The next week, I met with HR and my director and a legal representative, because once the word “compliance” enters a conversation, suddenly everyone wants minutes and approvals.

We reviewed my new job scope. We clarified responsibilities. We defined escalation authority. We mapped what I could approve, what required sign-off, what required legal review.

For the first time, the work I did wasn’t “extra.”

It was official.

It had a name. A structure. A budget line.

They called it oversight.

I called it finally telling the truth out loud.

After the meeting, I walked back to my desk and saw the vendor manager, Michelle, in the hallway. She looked tired, like she’d been carrying her own version of this problem for too long.

She stopped and nodded once.

“You were right to document,” she said quietly. “If you hadn’t—this could’ve gotten ugly.”

“It did get ugly,” I replied, and surprised myself with how calm I sounded.

Michelle’s mouth tightened. “You know what I mean,” she said. “Ugly in a way that lasts.”

We both understood what she meant: lawsuits, regulatory scrutiny, executive fallout, public disclosures, careers ending in one sentence.

Instead, the damage had been contained.

Not because the system was strong.

Because someone had cared enough to stitch it together until the right people were forced to see the seams.

Michelle hesitated, then said something that felt like an apology without actually being one.

“Our team… assumed your reconciliations were standard,” she admitted. “We didn’t realize the volume you were absorbing.”

I looked at her for a moment.

“That’s the problem,” I said. “Everybody assumes the person doing the invisible work will keep doing it forever.”

Michelle nodded slowly. “Yeah,” she said. “I guess we all learned that one this week.”

When she walked away, I sat down at my desk and opened my notebook—the same thick audit notebook the COO had flipped through like it was unnecessary.

I ran my fingers over the tabs.

It wasn’t just documentation.

It was proof that I had not been imagining it. Proof that my instincts were accurate. Proof that the system had been vulnerable long before the new executive arrived.

He didn’t create the flaw. He revealed it by removing the human layer that had been masking it.

In American corporate culture, there’s a strange romance around disruption. Around “breaking things” to build better systems. Around the idea that if you cut enough “redundant” steps, the truth will magically become simpler.

But financial systems don’t become simpler just because someone wants them to be.

They become riskier.

And risk doesn’t disappear. It relocates.

For years, the risk had been relocated onto my desk.

The moment I stepped away, the risk returned to the surface like oil through water.

That’s what executives don’t understand until it’s too late.

Every “redundant” process exists because at some point, someone got burned.

Every manual check exists because someone once trusted automation and paid for it.

Every annoying extra step exists because the world is messier than the vendor brochure says it is.

That night, I didn’t celebrate. I didn’t pour champagne. I didn’t text anyone “I told you so.”

I made dinner. I ate slowly. I took a shower. I slept.

And in the morning, I went back to work with a different kind of calm.

Not the calm of someone waiting to be recognized.

The calm of someone who understands her own value regardless of who admits it.

The COO avoided me for a while after that.

Not overtly. Not rudely. He was still polite in meetings. Still used my name. Still nodded when I spoke. But there was a stiffness there, a controlled distance.

He’d been embarrassed, and executives don’t like people who witnessed their miscalculation.

A month later, I saw his title change on the org chart.

Strategic Initiatives.

No direct reports. No operational control. No real leverage.

He hadn’t been fired, but everyone knew what it meant. The corporate version of being moved to the side of the stage until you choose to exit quietly.

People whispered. People speculated. People wrote their own stories about what happened. In big companies, truth is always edited by the need to protect reputations.

But the numbers didn’t care about reputations.

The numbers had already written the real story.

One afternoon, around the time the quarter closed and the building started breathing again, my old director stopped by my desk.

“How you holding up?” he asked.

I considered the question carefully.

“I’m fine,” I said. And it wasn’t a performance. “I just… I’m not doing invisible work anymore.”

He smiled, tired but genuine.

“Good,” he said. “Don’t.”

After he walked away, I opened a new document on my computer and started writing something I hadn’t written in years: a personal career plan.

Not because I suddenly believed in corporate ladders. I didn’t. I’d seen too much.

But because I realized something important: if you are the person who holds the system together, you have leverage. Not the petty kind. The real kind.

Not to threaten. To negotiate.

To set boundaries.

To make sure your work is visible enough that it’s respected and structured, not exploited.

To make sure the company can’t collapse into crisis the moment you take a day off.

To make sure the process isn’t you.

That was the real lesson.

Not that executives make dumb decisions.

Not that vendors overpromise.

Not that systems break.

The real lesson was this:

If your job is saving the company quietly, your job is also making sure you don’t become the company’s hidden failure point.

Because one day, someone will look at your work and call it redundant.

And if you’ve done your job correctly, the system won’t rely on your exhaustion to function.

It will rely on design.

And if they insist on cutting the design anyway?

Then the consequences won’t be personal.

They’ll be mathematical.

A week later, I received an email from legal with a final summary of the incident: vendor remediation steps, revised contract language, internal control improvements, audit schedule updates.

At the bottom was a line that almost made me laugh out loud:

“Going forward, manual reconciliation oversight will be maintained as a critical internal control.”

Critical internal control.

Three years of “basic invoice checking” suddenly had a name that sounded like what it had always been.

I printed that email and tucked it into my audit notebook behind the first tab.

Not as a trophy.

As proof.

Proof that the system finally admitted what my work had been doing all along.

I didn’t need revenge.

I didn’t need applause.

I needed the truth to be written somewhere other than my own mind.

Now it was.

And as I walked past the lobby that evening—the same lobby where the new COO had arrived weeks earlier with his crisp welcome badge and confident smile—I caught my reflection in the glass doors.

I looked… normal.

No cape. No dramatic victory. No cinematic ending.

Just a person who had done her job, documented reality, and refused to be the quiet patch that let everyone else pretend the machine was fine.

Outside, the city air was cold. Somewhere a siren wailed in the distance. People hurried down the sidewalk carrying coffees, briefcases, the weight of their own invisible work.

I adjusted my bag on my shoulder and kept walking.

The building behind me didn’t feel like it owned me anymore.

For the first time, it felt like I had simply passed through it—competent, calm, intact.

And that, more than any raise or title, was the thing I’d been fighting for the entire time.

Because in the end, the most dangerous word he said wasn’t redundant.

It was the belief behind it.

The belief that experience is optional.

That systems are simple if you demand they be.

That the person who understands the details is just slowing down the “real” work.

But the real work is the details.

The details are where the money goes.

The details are where mistakes hide.

The details are where accountability lives.

Ignore them, and the system will eventually teach you why they mattered.

Sometimes gently.

Sometimes with a red banner on a dashboard.

Sometimes with a seven-point-nine-million-dollar lesson that makes even the most confident executive sit down and finally, quietly, learn.

The week after the freeze felt like living inside an aftershock.

On paper, the crisis had been “contained.” Legal had its timelines. Finance had its reconciled numbers. Procurement had its revised vendor terms. The vendor had “accepted responsibility” in the careful language that means, Yes, we’ll pay because the evidence is too clean to argue with. The dashboards returned to green. The quarterly close moved forward.

But the building didn’t go back to normal the way people pretended it would.

Because what broke wasn’t only the system. What broke was the illusion that the system had been fine.

When you work long enough in a U.S. corporate office, you learn there are two versions of truth. There’s the one that makes it into the slide deck—sanitized, symmetrical, safe for executives to speak aloud. And then there’s the truth that lives in the quiet spaces: the hallway pauses, the Slack messages people delete, the way someone looks at you when they realize you were carrying something they never noticed.

That second truth was everywhere now.

People stopped at my desk more often, but not in the loud, congratulatory way that would have made HR uncomfortable. They stopped with a new kind of caution, a new kind of respect that felt almost… uneasy. Like they’d realized I wasn’t just “the invoice person.” Like they were recalibrating where I belonged in their internal map of the company.

A procurement analyst I barely knew came by on Monday morning and asked, too casually, “So… how did you spot that pattern again?”

I answered politely, because I’m not the kind of person who punishes curiosity, but I watched the way her eyes kept darting as if she expected me to be bitter.

I wasn’t bitter. Not exactly.

I was tired in a deeper place.

Not the kind of tired sleep fixes. The kind that comes from years of being the safety net no one thanks until the day they feel how far the fall is without you.

At lunch, I sat in the break room with my food and tried to eat slowly, deliberately, like a person who didn’t have to inhale meals between fires. A group at the table across from me kept their voices low, but office walls don’t need to be thin for gossip to travel. Gossip travels on intention.

“I heard it was almost eight million,” someone whispered, as if saying the number loudly would summon it again.

“I heard the vendor’s gonna get sued,” someone said.

“I heard it was the COO’s fault,” another voice, sharper.

“I heard some analyst refused to help and let it happen.”

That last one made my jaw tighten hard enough to ache.

It wasn’t the accusation itself—people in offices love to assign blame to the person with the least power because it’s safer than blaming the person with the title. It was how familiar it felt. How quickly the narrative tried to shift from accountability to scapegoating.

The American workplace has a strange relationship with competence. It craves it and resents it at the same time. It wants you to fix everything, but it also wants you to pretend you didn’t need to exist.

I stood up, dumped my trash, and walked out before I could say something that would make me look “difficult.”

In the elevator, my reflection stared back at me in the brushed metal. I looked the same as I had the week before: hair pulled back, neutral blouse, badge clipped to my waistband, eyes that learned a long time ago how to stay calm while chaos moved around me.

But something in me had shifted.

For years, I’d been trained—by managers, by system needs, by survival instincts—to take problems personally. To feel responsible in a way that went beyond my job scope. To quietly carry risk because I didn’t trust anyone else to carry it correctly. It was a habit that looked like professionalism but functioned like self-erasure.

Now, I could see the cost of that habit clearly.

The cost wasn’t just my time. It wasn’t just my evenings and weekends. It wasn’t just the way I’d learned to sleep with spreadsheets still scrolling behind my eyelids.

The cost was that I had made it possible for leadership to stay ignorant.

If you always fix it before anyone sees it, no one learns to prevent it.

If you always absorb the risk, no one acknowledges it exists.

And if you do that long enough, you don’t become “irreplaceable.”

You become the hidden weakness in the system.

That thought followed me back to my desk, and when I opened my email, there was a calendar invite waiting: Post-Incident Control Review – Mandatory. Attendees: Finance Leadership, Legal, Procurement, Vendor Oversight. Location: Conference Room 14B.

Mandatory meetings in corporate life are where truth gets rehearsed. People don’t come to learn; they come to align. They come to make sure everyone’s story matches the approved version.

I accepted the invite without hesitation. Not because I wanted to argue. Because I wanted my documentation to be present in the room where narratives were being built.

At 2:00 p.m., I walked into 14B and found the room already half full. The glass walls made everyone visible to the hallway, which always creates an odd performance layer—people keep their voices low, their expressions controlled, because they know anyone walking by can see who looks upset.

The CFO’s chief of staff sat near the screen, flipping through a binder. Legal counsel had a laptop open with a sterile, unreadable expression that said, I’m here to reduce liability, not to soothe feelings. Procurement leadership looked like they’d spent the morning chewing on numbers that didn’t taste good.

And the COO sat at the far end of the table, posture stiff, hands clasped tightly enough that his knuckles looked lighter than the rest of him.

He looked smaller without his confidence.

Not physically. Executives rarely look physically smaller. But the aura—the effortless dominance that comes from believing you can say anything and the room will rearrange itself around you—was gone.

When I took a seat, the COO didn’t look at me.

That was fine. I wasn’t there for eye contact.

The meeting started with Legal walking through the timeline in a voice that sounded almost bored, which is how lawyers talk when the numbers are catastrophic. The slides showed dates, triggers, decisions, escalation points. On the surface, it looked like a clean story: vendor irregularities detected, internal controls activated, incident contained, remediation underway.

But then the slide appeared with the root cause summary.

“Removal of manual reconciliation oversight created control gap.”

The phrase made the room tighten.

Control gap. A sterile term for something that, in practice, means someone cut the only thing stopping a mess from becoming a disaster.

Legal counsel paused on that slide, letting it sit. Then, calmly: “We need to confirm why the control was removed and how to prevent similar unilateral changes going forward.”

The CFO’s chief of staff glanced at the COO, waiting.

The COO cleared his throat.

He spoke carefully, like every word was being weighed for future use.

“I directed the process change based on my understanding of vendor automation capabilities,” he said.

He didn’t say, I was wrong. He didn’t say, I didn’t read the documentation. He didn’t say, I underestimated the system.

He said the corporate version: based on my understanding.

Then Legal counsel asked, in a neutral tone that was somehow more dangerous than accusation: “Did you have a signed record of the change request?”

I could have stayed silent. The signed memo was already in the packet. Everyone in that room had seen it.

But silence lets people pretend.

So I spoke, calmly, without heat. “Yes,” I said. “I drafted a directive memo summarizing the change, and it was signed.”

Every head in the room turned slightly. Not in shock—they already knew. In attention.

When you become visible in a room like that, it’s not flattering. It’s like a spotlight turning on in a space that wasn’t built for you. It warms you and exposes you at the same time.

Legal counsel nodded once, as if checking a box. “Understood. Going forward, process changes impacting financial controls will require cross-functional approval. At minimum: finance, procurement, legal, and internal audit.”

Internal audit. The words made the COO’s mouth tighten. Internal audit is the ghost in every executive’s closet. It doesn’t care about titles.

The meeting continued. More controls. More approvals. More “lessons learned.”

And then, near the end, something happened I didn’t expect.

The CFO’s chief of staff looked directly at me and said, “We need to define ownership for reconciliation oversight moving forward. Who is accountable?”

It wasn’t a trick question. It was the kind that determines whether a job becomes respected or exploited.

The room waited.

I felt the old reflex rise in me, the one that wanted to say, I can handle it, don’t worry. The reflex that had kept me useful and underpaid for years.

I swallowed it.

“I can own the oversight,” I said steadily, “but not as an informal safety net. It needs to be formalized as a control function with documented authority, backup coverage, and clear escalation lanes. One person should not be the only barrier between the company and vendor risk.”

The words landed heavier than I expected.

The CFO’s chief of staff nodded slowly, and for the first time, I saw something like relief in their eyes. Not relief that I would fix it again, but relief that someone had finally said out loud what everyone had been avoiding.

The COO looked down at the table.

Not angry. Not offended.

Just quiet.

When the meeting ended, people stood, gathered their binders, filed out in that professional shuffle of people who want to look busy instead of shaken. I stayed seated for a moment, letting my heartbeat settle.

Then I stood, picked up my notebook, and walked toward the door.

The COO spoke behind me.

“Can we talk?” he asked.

The room was mostly empty now. Just us, the faint hum of the projector cooling down, the quiet of a glass-walled space that had held too much tension for too long.

I turned slowly.

He looked uncomfortable, and executives hate discomfort because it makes them feel like normal people.

“I’m in the middle of a lot,” he said, as if he needed to justify even this. “But I wanted to say… I underestimated what you were doing. And I’m sorry.”

The apology wasn’t dramatic. It wasn’t perfect. It had that careful corporate edge, like he didn’t want to admit too much because admissions can be expensive.

But it was still an apology.

My first emotion wasn’t satisfaction.

It was something sharper: grief.

Not grief for him. For the years.

For the times I’d tried to explain and been brushed off. For the nights I’d stayed late because I didn’t trust anyone else to catch what I could catch. For the way I had convinced myself that invisibility was safer than insisting on recognition.

I kept my voice even. “Thank you,” I said. “But I need you to understand something.”

He nodded, cautiously.

“This wasn’t just a bad week,” I said. “This was years of risk that never got addressed because I was absorbing it quietly. If you want to lead operations, you can’t cut what you don’t understand. And you can’t treat expertise as optional.”

He swallowed, jaw tight.

“I know,” he said quietly.

I studied his face for a moment. People love to paint executives as villains, but most corporate damage isn’t done by evil. It’s done by confidence paired with ignorance and rewarded by a system that confuses boldness with competence.

He wasn’t evil. He was dangerous in the way a person can be dangerous when they believe their instincts are superior to other people’s experience.

“I’m not interested in humiliating you,” I said. “I never was. I wanted the company to be protected. I wanted the vendor to be held accountable. I wanted the truth to be seen.”

He nodded again, once, like someone receiving something heavy. “I get it,” he said.

Then he hesitated, and I could tell he wanted to say something else but didn’t know how. Finally: “What do you want?”

The question hung there.

It wasn’t about money—though money mattered. It wasn’t about title—though title mattered. It wasn’t about revenge—though people expected that.

It was about structure.

“I want the work to be built into the system,” I said. “Not into me. I want formal controls, documented escalation, and coverage. I want a job that doesn’t require me to be exhausted for it to function.”

He looked down at his hands. “Fair,” he said.

When I left the room, my heart felt strangely steady.

Not triumphant. Not bitter.

Steady.

That night, I sat at my kitchen table in my apartment and opened my laptop, not to work late, but to write something I’d been avoiding for years: boundaries.

I typed a list. Not lofty. Not motivational.

Concrete.

No off-the-record reconciliations. No “quick looks” without documentation. No last-minute fixes outside the control process. No absorbing vendor risk without reporting it. No staying late unless the work is planned and recognized, not reactive and invisible. No being the emergency plan.

Then I wrote the other list—the one that scared me more:

What I would do if the company resisted those boundaries.

Request formal escalation. Document refusal. Protect myself. Update my resume.

Because here’s the truth nobody tells you in corporate America: loyalty is often just a name we give to fear. Fear of losing your job. Fear of being labeled “not a team player.” Fear of becoming expendable.

But if a system relies on your fear, it’s not a system worth saving with your health.

The next day, my director called me into his office. The door was open—an intentional move. Open door meant this conversation was supposed to feel transparent, safe.

He gestured to a chair and smiled, the kind of smile managers use when they’re about to deliver something they think you should be grateful for.

“I wanted to go over the updated role,” he said, sliding a folder toward me.

I opened it. New title. New compensation band. Revised scope: Vendor Reconciliation & Controls Lead. Formal ownership. Escalation authority. Cross-functional alignment.

I looked at the salary number.

It was significant. Not life-changing wealth, but enough to correct years of being undervalued. Enough to make my stomach unclench in a way it hadn’t for a long time.

My director watched my face, as if trying to read whether I would cry or smile or negotiate.

I didn’t do either.

“I appreciate this,” I said calmly. “But I want to add one condition.”

His eyebrows lifted slightly. Managers don’t like “conditions” from people they’ve been treating as quiet labor for years.

“What?” he asked.

“Backup coverage,” I said. “A documented secondary owner trained on the process. And a rule: no unilateral removal of reconciliation controls without cross-functional approval.”

He leaned back. “That’s… a lot,” he said carefully.

“It’s not,” I replied. “It’s what a stable system requires.”

He held my gaze, and I could see the old dynamic trying to reassert itself—the assumption that I would accept whatever they offered because I was lucky to be seen.

I didn’t blink.

After a moment, he nodded. “Okay,” he said. “We can do that.”

It wasn’t generosity. It was recognition that the company had just paid almost eight million dollars in the currency of fear and embarrassment, and it didn’t want to pay again.

“Good,” I said.

I signed the offer with a steady hand.

Walking back to my desk, I felt something unfamiliar: space.

Space in my chest. Space in my head. The kind of space that appears when you stop bracing for impact.

Over the next few weeks, I rebuilt the reconciliation process the way it should have been built from the beginning: not as my private craft, but as a structured control system. We documented every step. We defined thresholds. We established escalation triggers that didn’t rely on my intuition alone. We created dashboards that leadership could see. We required vendor explanations in writing. We built a cadence of review meetings that couldn’t be skipped just because someone wanted to “move fast.”

And slowly, something shifted in the building.

People stopped acting surprised when I raised concerns. They started asking earlier. They started looping me in before decisions were made instead of after problems appeared. I wasn’t just a repair person anymore.

I was part of design.

There were still moments where the old patterns tried to return.

A senior manager once messaged me, “Hey, can you just adjust this one thing real quick? We don’t need to log it.”

I stared at the message for a moment, heart beating faster, because my body remembered the old cost of saying no.

Then I replied, politely: “Happy to review. Please submit a ticket so it’s documented and traceable.”

A pause. Then: “Okay.”

And that was it.

No explosion. No retaliation. No secret punishment. Just a small moment of boundary held, and the world continued.

It felt almost absurd, how much power I had given away for so long just because I assumed saying no would end me.

The vendor, on their side, changed too.

They sent new contacts. New compliance officers. They offered “enhanced monitoring” and “process improvements” and “commitment to partnership.” Their language became careful. Their emails included more people on CC. Their adjustments came with explanations instead of assumptions.

They weren’t suddenly virtuous. They were scared.

And fear, when it’s pointed at the right place, can improve behavior.

One afternoon, the vendor’s senior director called into a review meeting and said, “We want to thank your team for your diligence.”

I almost laughed. Diligence. That’s what they called years of me cleaning their mess.

But I kept my face neutral and said, “We want accuracy. That’s the partnership standard.”

After the call, my new backup analyst—someone younger, eager, still believing corporate life is mostly rational—looked at me and said, “How did you do this alone for so long?”

The question was honest. Not admiration. Concern.

I thought about my answer carefully, because I didn’t want to glamorize it.

“I didn’t do it alone,” I said. “The system did it. I just became the person it landed on. And I didn’t push it back where it belonged until it got loud.”

She frowned. “Why not?”

I stared at the monitor for a moment, then said the truth: “Because I thought being essential was the same as being valued.”

The young analyst looked at me like she wanted to argue, like she wanted to say, But you are valued now.

And she was right, in a way.

But value gained through crisis is a particular kind of value. It’s conditional. It’s reactive. It appears when the building shakes.

I wanted her to learn something that took me too long:

Don’t wait for disaster to justify your boundaries.

A few months later, the company held an internal “controls training” session. It was framed as professional development, a learning opportunity, a culture shift. They asked me to present part of it.

Me. The person who used to be invisible.

I stood at the front of a conference room with a slide deck behind me and a room full of managers and analysts looking at me like I had authority, and I felt something tug in my chest.

Not pride.

Sadness.

Because it shouldn’t have taken an eight-figure near miss for this to happen.

But I spoke anyway. I spoke clearly. I spoke in the language people in U.S. corporations understand: risk, control, exposure, accountability. I used simple examples. I showed how small anomalies compound. I explained why “automation” is not a magic word, why vendor roadmaps are sales documents, why manual checks exist, why documentation isn’t bureaucracy—it’s protection.

And I watched faces shift as people finally understood that the work I did wasn’t paranoia.

It was math.

After the session, a manager from another department approached me. He looked uncomfortable, like he didn’t know whether he was allowed to be honest.

“I always thought you were… just, you know, detail-oriented,” he said awkwardly.

I smiled politely, because I understood what he meant. He meant he thought I was obsessive. He meant he thought I was the kind of worker who makes things harder than they need to be.

“I am detail-oriented,” I said. “Because details are where money hides.”

He nodded slowly. “Yeah,” he said. “I get that now.”

He walked away, and I realized something important: understanding changes how people treat you. But they don’t seek understanding. They wait until ignorance becomes expensive.

That’s why documentation matters.

Documentation is truth that doesn’t require belief.

One Friday evening, months after the crisis, I stayed late by choice—not because I was putting out fires, but because I wanted to finish a controls roadmap before the week ended. The building was quieter. The fluorescent lights felt less oppressive when they weren’t paired with panic.

As I packed up, I noticed the COO—now in his quiet strategic role—walking through the corridor. He looked like someone trying to be invisible in a building that used to orbit him.

He saw me and paused.

“Hey,” he said.

“Hey,” I replied.

He hesitated, then stepped closer, careful like he didn’t want to intrude.

“I’m leaving,” he said.

The words landed softly. Not dramatic. Not announced. Just stated.

I nodded once. “Okay.”

He looked relieved that I didn’t react like I was winning something.

“I wanted you to know,” he continued, “I used your process changes in my exit report. I told them the control work you built should be protected. That it shouldn’t be tied to one person.”

I stared at him for a moment, surprised.

“Thank you,” I said, and meant it.

He let out a breath like he’d been holding it. “I didn’t come in trying to hurt anyone,” he said quietly. “I really thought… cutting steps would make things better.”

“I know,” I said. “Most people do.”

He nodded. Then, after a pause: “You’re good at what you do.”

The compliment was small, but it carried weight because it came from someone who had tried to erase my work.

“I know,” I said, not arrogantly, just factually.

He blinked, then a faint smile touched his mouth, like he wasn’t sure whether to be offended or impressed.

“Good,” he said. “You should.”

Then he walked away, his footsteps soft on the carpet.

I stood there for a long moment, feeling something settle.

Not forgiveness. Not friendship.

Closure.

The kind that comes when someone who dismissed you finally acknowledges reality, not because you begged them to, but because the world forced them to see.

On the drive home, the city lights blurred past my windshield, and I realized I was thinking about something I hadn’t thought about in years: what I wanted next.

Not what I needed to survive.

What I wanted.

In the early years, I didn’t let myself want much. Wanting felt dangerous because it led to disappointment. So I kept my goals small: pay rent, stay employed, keep my head down, be useful. I told myself that was maturity, that was responsibility.

But it wasn’t life.

It was endurance.

Now, with the job formalized, the process stabilized, my evenings no longer consumed by silent emergency work, I felt a strange open space where exhaustion used to live.

And open space demands a question:

What do you do with freedom?

At home, I sat on my couch with my laptop and opened a document. I didn’t label it “career plan” or “five-year goals.” That kind of language makes me cringe.

I labeled it: What I want.

I wrote, slowly:

I want work that respects controls, not worships speed.

I want to build systems that don’t rely on burnout.

I want to teach younger analysts how to protect themselves.

I want to never again be invisible by accident.

Then I wrote another line, the one that felt like a confession:

I want to stop being afraid that saying no will destroy my life.

Because that fear had shaped everything. It had shaped my silence. It had shaped my late nights. It had shaped my willingness to absorb risk without recognition.

That fear wasn’t just professional.

It was personal. It was the kind you develop when you grow up learning that conflict means punishment. Even if my family wasn’t part of this story, the pattern was the same: if you make yourself small enough, maybe you won’t be targeted. If you fix everything quietly, maybe you won’t be blamed.

But adulthood teaches a brutal truth: if you make yourself small, the world doesn’t protect you. It uses you.

So I started practicing a new habit.

Not being loud.

Being clear.

Clear emails. Clear escalation. Clear boundaries. Clear documentation.

Clarity is kindness in systems. It’s protection. It’s how you stop a company from turning your silence into their convenience.

A year later, the vendor relationship looked different. Not perfect, but different. The quarterly review meetings included compliance. Our internal controls had real dashboards. The process didn’t drift because it wasn’t reliant on my gut alone. If something moved out of range, the system flagged it, and the response was documented and tracked.

The younger analyst I trained—my backup—became strong enough that she didn’t need me to catch everything. Watching her was one of the most quietly satisfying parts of the entire aftermath. Not because I wanted a protégé, but because I wanted proof that the system could be stronger than one person.

One afternoon, she messaged me: “Flagged an adjustment pattern. Looks like it’s trending again.”

My stomach tightened, instinctively.

Then I breathed and replied: “Good catch. Log it. Escalate. Loop in compliance.”

She did.

And for the first time, I watched the process work without my hands on every lever.

That was the real victory.

Not a raise. Not a title. Not the COO’s apology.

A system that didn’t need my exhaustion to stay honest.

Sometimes, late at night, I still thought about the moment he said redundant.

It replayed in my head like a scene from a movie that could have gone differently. In some version, I argued. I insisted. I begged. I tried to make him understand.

And in that version, maybe I would have sounded emotional. Maybe he would have labeled me difficult. Maybe he would have cut me anyway and left no paper trail.

In this version—the one that actually happened—I didn’t beg.

I documented.

I stepped away.

And reality did the explaining for me.

The truth is, that’s what made the ending feel clean, even if corporate never is.

Not because someone got humiliated. Not because money was lost. Not because the vendor got punished.

Because for once, the person who did the invisible work didn’t have to scream to be heard.

She just had to stop covering the cracks.

And when the cracks finally showed, everyone had to look.

I learned something else too—something I didn’t expect.

There’s a difference between being right and being respected.

Being right is private. It’s the quiet satisfaction of knowing your numbers were true.

Being respected is structural. It’s when the system changes so that your expertise becomes part of the decision-making, not an afterthought.

I didn’t want to be right.

I wanted to be respected enough that being right wouldn’t require disaster.

Now, when I walk into the office—badge clipped, coffee in hand—I don’t feel the old tension in my shoulders. I don’t feel like I’m sneaking my value into the building through late nights and quiet fixes.

I sit down, open the dashboard, review the controls, and do the work inside the light.

And when someone new joins—another executive, another manager with a fresh badge and shiny confidence—and they look at a process and call it redundant, I don’t feel fear anymore.

I feel calm.

Because now the system has memory beyond me.

Now the controls have names, owners, approvals.

Now the company knows what it costs to pretend details don’t matter.

And if someone tries to forget?

They won’t just be ignoring a person.

They’ll be ignoring a documented control framework designed to keep the company safe.

That’s what I wanted all along.

Not to be the hero.

To make sure the company stopped needing one.

So yes—numbers always tell the truth.

But the deeper truth is this:

When you stop protecting people from the consequences of their own arrogance, you aren’t being cruel.

You’re being honest.

And honesty, in a system built on shortcuts and ego, feels like an earthquake.

But after the shaking, something better can be built—something that doesn’t depend on one exhausted person to hold it all together.

That’s what I built.

Not with revenge.

With clarity.

With paper trails.

With boundaries.

With the quiet courage to step back and let reality speak in the only language corporate America truly understands:

the math.

News

At the funeral, my grandpa left me a passbook. My father threw it in the trash. “It’s old. This should have stayed buried forever.” Before returning to base, I still stopped by the bank. The manager turned pale and said… “Ma’am… call the police. Now.

The bank manager didn’t shout. He didn’t have to. The color left his face so fast it looked like someone…

ON MY WEDDING DAY, MY SISTER WALKED DOWN THE AISLE IN A WEDDING DRESS AND SAID, “HE CHOSE ME!”MY MOM CLAPPED AND SAID, “WE KNEW YOU’D GET IT.”MY GROOM JUST LAUGHED, “YOU HAVE NO IDEA WHAT’S COMING.”THEN, THEN, HE PLAYED A RECORDING ON HIS PHONE, AND EVERYTHING CHANGED.

The stained-glass windows caught the late-morning Chicago light and broke it into shards of color—ruby, sapphire, honey-gold—spilling across the aisle…

HE SAID “CLEVELAND” I SAW HIM IN PARIS AT GATE 47 TERMINAL HE WAS NOT ALONE WITH PREGNANT GIRL I ZOOMED IN CLOSER TOOK THE SHOT 4K POSTED TO HIS FEED TAGGED HIS BOSS HE DIDN’T KNOW…

The upload bar slid to the right with a quiet finality, followed by the soft green check mark that meant…

THE VP’S DAUGHTER MOCKED MY “THRIFT-STORE RING” DURING A STAFF MEETING. I SAID NOTHING. 2 HOURS LATER, A BILLIONAIRE CLIENT SAW IT – AND WENT WHITE. “WHERE DID YOU GET THIS?” HE ASKED. I SAID MY FATHER’S NAME. HE STOOD. “THEN THEY HAVE NO IDEA WHO YOU ARE…

The glass conference room on the thirty-seventh floor looked like it had been designed by someone who hated warmth—all sharp…

EMPTY YOUR ACCOUNTS FOR YOUR BROTHER’S STARTUP,” DAD ORDERED. THEY’D ALREADY SPENT HIS FIFTH ‘BUSINESS LOAN.’ I QUIETLY CHECKED MY OFFSHORE PORTFOLIO. THE FRAUD DEPARTMENT CALLED DURING DESSERT.

The roast hit the table like a peace offering that nobody meant. Butter, rosemary, and heat rolled off the carved…

EVERY TIME I TRIED TO HUG HER, MY STEPDAUGHTER WOULD STEP BACK AND SCREAM HYSTERICALLY, CALLING FOR HER FATHER. MY HUSBAND IMMEDIATELY FLEW INTO A RAGE AND ACCUSED ME OF ABUSING HIS DAUGHTER. I INSTALLED AK CAMERA IN THE GIRL’S ROOM AND…

Dawn broke over the quiet suburb like a lie told softly. The lawns were trimmed to perfection, the American flags…

End of content

No more pages to load