The first sign something was wrong wasn’t the rash.

It was the way the fluorescent lights above my chemistry lab suddenly looked too bright—like someone had turned the world’s contrast up and left my body behind to deal with it.

Third period at Lincoln High, somewhere in the sprawl of a mid-sized American school district that loved banners about “Student Safety” and “Zero Tolerance.” The kind of place where the football field had better lighting than the nurse’s office, and the front entrance had a framed photo of the superintendent shaking hands with a state senator. A place that ran on rules, forms, and the quiet assumption that teenagers exaggerated everything.

I stared down at my forearms while Mr. Kaplan droned on about covalent bonds. Small red welts had started to bloom across my skin—neat at first, like little islands rising in a red sea—then multiplying fast, connecting, spreading, turning my arms into a twisted connect-the-dots puzzle.

Ten seconds.

That’s all I gave myself before the second sign hit.

My throat tightened.

Not like a sore throat. Not like nerves. Like an invisible hand had found the inside of my airway and started twisting.

I didn’t panic at first, because panic was a luxury. Panic meant you didn’t know what was happening. I knew exactly what was happening, because my body had been trying to take me out since I was a baby.

Severe tree nut allergy. Anaphylaxis risk. EpiPen carrier. The words weren’t dramatic. They were facts, as permanent as my name.

I’d worn that truth around my wrist for as long as I could remember: a medical alert bracelet with bold, blunt lettering that didn’t care if you believed it or not.

SEVERE ALLERGY – TREE NUTS – EPINEPHRINE

Some days it felt like jewelry. Most days it felt like a warning label slapped on a product that might malfunction at any moment.

And now it was happening. Here. In chemistry. On a random school day that had started like any other—bad cafeteria coffee smell in the hallway, somebody blasting music from their phone, announcements about a canned food drive, the American flag hanging limp in the corner like it was bored.

My lungs pulled in air and didn’t get enough. It wasn’t that I couldn’t breathe at all. It was worse. I could breathe just enough to know I wasn’t getting enough.

I shoved my chair back. The metal legs squealed against the tile. A couple of heads turned. Mr. Kaplan stopped mid-sentence.

“Where do you think you’re going?”

I couldn’t waste oxygen explaining. I grabbed my backpack, the one with a clearly labeled pocket where my EpiPen lived like a tiny plastic guardian angel, and stumbled for the door.

The hallway tilted. Not like I was drunk—like my body had decided gravity was optional now. My heart pounded fast, desperate, trying to outrun the crisis. My vision blurred at the edges, dark flecks dancing like TV static in my peripheral sight.

Fifteen minutes, my allergist used to say. Sometimes less. Sometimes a lot less. Minutes matter.

I passed lockers plastered with sports flyers and prom posters and “Be Kind” stickers. I passed a trophy case full of shiny proof that this school could protect glass objects better than it protected kids.

The nurse’s office door was ahead, beige and boring and far too normal for a place where people came when something was wrong.

I pushed inside.

The air smelled like antiseptic and stale coffee. The lights were the same harsh fluorescent glare as the hallway, but in here it felt personal, like an interrogation room.

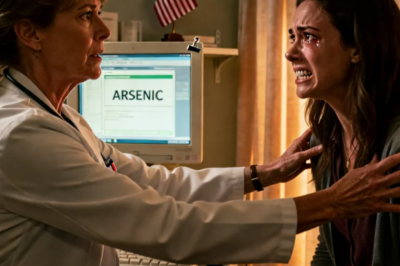

Nurse Vivian Brennan looked up from her desk with the irritated expression of someone whose day had just been inconvenienced by your body failing.

She wasn’t old, maybe mid-forties. Hair neat. Lipstick the color of “I have authority.” A lanyard around her neck with keys and an ID badge that said RN in big letters, as if the universe needed reminding.

I tried to speak.

Nothing came out right.

My tongue felt thick. My mouth was full of cotton. My throat was narrowing, closing the way a drawbridge lifts—slow enough that you can watch, fast enough that you can’t stop it.

I pointed to my bracelet.

Then to my backpack.

Then, because I was starting to lose the ability to coordinate my thoughts, I mimed an injection into my thigh like some desperate charades game.

She stood up slowly. Not urgently. Slowly, like she had all the time in the world and I was just a student who wanted to skip class.

She walked over and took my forearm in her hand, turning it to inspect the hives with calm, detached interest.

“Looks like contact dermatitis,” she said, voice clinical and dismissive. “Probably touched something in the lab.”

I shook my head so hard the room swayed.

I forced air out of my tightening throat.

“EpiPen,” I wheezed. “Need it. Now.”

My voice was thin, ragged. The word came out broken, like my airway was chewing it up on the way out.

Her eyebrows lifted just slightly, the way adults do when they think a teenager is being theatrical.

“I decide what medication is appropriate during school hours,” she said. “That’s school policy. EpiPens are for severe reactions only.”

My chest tightened like someone had cinched a belt around my ribs and started pulling.

“It is,” I tried to say. “It’s severe.”

But it came out as: “It… is…”

Because I couldn’t get enough air to form the rest.

Nurse Brennan crossed her arms, settled into the posture of someone prepared to win an argument.

“And this doesn’t look severe to me,” she said. “You’re breathing fine.”

I wasn’t.

Each inhale was a struggle, a whistle through swelling tissue. My body wanted to cough, to gag, to do anything to clear a path that was closing anyway.

I fumbled with my backpack zipper. The world felt disconnected, like my brain was trying to send messages through wet cement. Fingers that usually typed a hundred texts a day suddenly couldn’t manage a zipper.

I got it open enough to reach for the pocket.

Nurse Brennan stepped forward and grabbed the backpack right out of my hands.

“I’ll handle this,” she said, like she was calming a child. “Sit down before you hyperventilate and make it worse.”

Hyperventilate. Like I had extra air to waste.

She walked to the medication cabinet—metal and glass—and unlocked it with a key from her lanyard. Then she opened it, shoved my backpack inside, and shut it again.

Click.

The lock snapped closed with a finality that made my stomach drop.

My life-saving medication was now fifteen feet away, behind glass, inside a cabinet that belonged to her.

I stared at it like it was a bank vault holding my oxygen.

I tried to lunge forward.

My legs didn’t cooperate. My balance wobbled. The world swam.

She turned back with two little tablets in her palm and a paper cup of water.

“Take these,” she said. “Benadryl. Then lie down on the cot. You’ll feel better in twenty minutes.”

Benadryl wouldn’t stop anaphylaxis.

It might help itching. It might help hives. It would not pry open a swelling airway.

My head shook on its own, frantic. I tried to speak again, but my voice was disappearing, replaced by a harsh wheeze.

“EpiPen,” I managed. “Please.”

She reached out and patted my shoulder.

The pat was soft. The message was brutal.

“You’re not dying,” she said. “You’re anxious. Deep breaths.”

Deep breaths.

Like I wasn’t already begging my lungs for every molecule of oxygen.

Like my body hadn’t been trained by years of severe allergy to recognize this exact cascade: hives, swelling, airway tightening, the terrible narrowing tunnel where your world shrinks to one goal—air.

I swallowed the pills because my options were collapsing as fast as my throat. The water sloshed as my hands shook. The taste was chalky, useless.

I stumbled to the cot in the corner and collapsed onto it.

The hives spread to my chest, crawling up my neck. I could feel my lips swelling, my tongue growing heavy. My face felt wrong, as if my own skin no longer fit.

I reached for my phone—muscle memory, the instinct to call my mom, to get someone real on the line, someone who would believe me without needing to “authorize” my survival.

My fingers failed. The phone slipped from my hand and clattered to the floor.

Nurse Brennan picked it up with the same calm speed she’d used to lock away my EpiPen and set it on her desk.

Out of reach.

“No phones during treatment,” she said, as if that rule mattered more than my oxygen level.

I tried to sit up.

My vision narrowed. The room dimmed at the edges, closing in like curtains.

My breathing became a thin, high-pitched sound. Not enough. Not enough.

I’d had three severe reactions before that day.

When I was six, at a birthday party, someone handed me a cookie. Almond flour. Within minutes my face swelled and I couldn’t breathe. Someone used my EpiPen. Paramedics came. Hospital. Steroids. IV fluids. Doctors saying the same thing with the same serious look: “Minutes matter. Don’t delay epinephrine.”

When I was eleven, it happened at a restaurant. “No nuts,” my parents had told them. Cross-contamination. A smear of something invisible. My throat tightened. EpiPen. Ambulance. Hospital. Again: “Minutes matter.”

When I was fourteen, at summer camp, a counselor had acted fast. EpiPen. Saved.

Every time, the adults did what they were supposed to do.

So when my parents enrolled me at Lincoln High three months earlier, they did everything the American system asked of them. Meetings with administration. Medical paperwork. A doctor-signed action plan. Three backup EpiPens stored in the nurse’s office. Everyone nodding solemnly, promising they took student safety seriously.

I’d met Nurse Brennan during that meeting.

She’d seemed competent then. She nodded while my mom explained my allergy history. She initialed the line that mattered most—the one stating I was authorized to self-administer at any time without permission.

She signed it.

She signed my right to save my own life.

And now she was undoing it with a locked cabinet and an attitude.

My chest convulsed, trying to pull in air through a narrowing hole.

I tried to push off the cot again. My legs gave out. My body felt both too heavy and too light, like it couldn’t decide whether to collapse or float away.

The ringing in my ears started, that distant high tone that meant my brain was losing its oxygen supply.

I knew that feeling.

It was the edge of black.

The last thing I saw before everything went out was Nurse Brennan glancing at her watch and making a note on her clipboard, like she was tracking a late arrival, not a medical emergency.

Then the world snapped off.

When I came back, it was chaos.

Bright lights. Shouting voices. The sensation of air being forced into my lungs through a mask. My arm burned where a needle had gone in. My heart raced like it was trying to restart itself from sheer stubbornness.

I blinked and saw uniforms.

Paramedics.

One of them—woman, dark hair pulled into a ponytail, eyes sharp but kind—noticed me looking around.

“Stay still,” she said, voice steady. “You’re okay now. We got to you.”

Got to me.

That meant there had been a moment when I wasn’t okay. When it was close.

My throat still felt swollen, but I could breathe. Oxygen flowed into my face from the mask. An IV line ran from my arm to a bag of clear fluid.

Somewhere in the blur, I heard a time called out. A report being given. A radio crackling.

“Sixteen-year-old male, severe allergic reaction, found unresponsive in school nurse’s office. Epinephrine administered… patient regained consciousness…”

The older paramedic—a man with gray stubble and the exhausted look of someone who’d seen too much—was on his phone, speaking low but angry.

“If that teacher hadn’t walked by and looked through the window, the kid wouldn’t be here,” he said. “Nurse was sitting there like it was nothing.”

I tried to turn my head. Pain flared in my throat.

Teacher.

Window.

It took my brain a second to connect it.

Mr. Kaplan.

He must have come looking for me. Wondered why I’d left class. Looked through the nurse’s office window and seen me unmoving on the cot.

And then he’d done what Nurse Brennan refused to do.

Called for help.

The ambulance doors opened. Cold air hit my face. More voices, more movement, a blur of the emergency department swallowing me whole.

“County General,” someone said—one of those big American hospitals with a name that sounded like it belonged on a government sign.

A doctor appeared, young and efficient, eyes scanning monitors.

“Time from onset to epinephrine?” he asked.

“Estimated twenty to twenty-five minutes,” a paramedic replied. “School nurse delayed.”

The doctor’s jaw tightened.

He leaned close enough that I could see the focus in his eyes.

“Can you hear me?” he asked, voice calmer. “I’m Dr. Foster. You had a severe allergic reaction. We’re going to take care of you.”

I nodded weakly.

He asked what I’d eaten, what I’d touched.

I didn’t know. That was the terrifying part. I’d been in chemistry. A lab bench. Maybe residue. Maybe a classmate’s snack. Maybe something so small it didn’t matter until it did.

My parents arrived like a storm.

I heard my mom first—voice high, frantic, demanding to know where I was.

Then she burst into the room, saw me pale and swollen and wired to monitors, and broke down.

My dad was right behind her, but he didn’t cry. His face went white in a way that looked almost unreal, like all his blood had drained out and left only anger behind.

My mom grabbed my hand, squeezing like she could keep me here by force.

“They said the nurse wouldn’t give you your medication,” she said, voice trembling. “Tell me that isn’t true.”

So I did.

I told them about the hives. The tightening throat. The nurse’s office. The locked cabinet. The Benadryl. The clipboard. The blackness.

My mom’s tears kept coming, unstoppable.

My dad’s expression changed in slow motion—from shock to fury to something cold and controlled that made me realize, with a strange clarity, that Nurse Brennan had made an enemy she couldn’t out-policy.

He stepped into the hallway and made a call.

I could hear him, voice quiet but lethal, the way people speak when they’re holding themselves back from exploding.

“This is Leonard Ashford,” he said. “My son is in the emergency room because a school employee refused emergency medication during a severe allergic reaction. I need to speak to the principal. Now.”

A pause.

“I don’t care if he’s in a meeting.”

Another pause.

“Transfer me or I’m calling the school board and our attorney at the same time.”

When he came back into the room, Dr. Foster returned too, checking my vitals, speaking in that careful professional tone that still carried a sharp edge.

My mom asked the question every parent asks when the worst almost happens.

“How bad was it?”

Dr. Foster looked at her with sympathy.

“Based on the paramedics’ report,” he said, “your son was in respiratory arrest when they arrived. He wasn’t breathing effectively. Another few minutes and we would be having a different conversation.”

My mom made a sound like she’d been hit.

My dad’s hands clenched.

Dr. Foster continued, more blunt now, like he couldn’t stand the idea of anyone minimizing what had happened.

“A nurse preventing a minor from accessing emergency medication is serious,” he said. “We’re required to report this. There will be investigations.”

Investigations.

The word sounded polite. What happened didn’t feel polite.

It felt like watching a locked cabinet hold the line between you and oxygen.

Over the next hours, people came and went.

A hospital administrator. A social worker. A woman with a badge who asked questions like she’d done this before, calm and thorough and not fooled by “school policy.”

Then the principal showed up.

Gregory Whitman. Suit jacket. Forced concern. The kind of man who probably signed off on safety drills and congratulated himself for it.

He said all the expected things: how sorry he was, how seriously the school took student safety, how they’d conduct a full review.

My dad stared at him like he was seeing through him.

“A review of what?” my dad asked, voice flat. “My son nearly stopped breathing because your nurse locked away emergency medication. There’s nothing to review. There’s accountability.”

The principal shifted, uncomfortable.

“We need to gather all the facts,” he said, defaulting to bureaucracy like it was a shield. “Nurse Brennan has been with the school for years—”

“She has an incident now,” my mom snapped, wiping her face with the heel of her hand. “And our son nearly died.”

The principal tried to talk about procedures. Internal processes. Protocol.

My dad cut him off.

“We want the medical records from her office,” he said. “We want the action plan. We want names. We want any security footage. And we want to know what you’re going to do to make sure this never happens again.”

The principal promised everything and left like the room was on fire.

That night, my parents hired an attorney.

Amanda Cho. Malpractice and institutional negligence. Sharp-eyed, calm, the kind of woman who listened without interruption and then spoke like she’d already mapped out the next ten steps.

When she finished hearing what happened, she didn’t hesitate.

“You have a strong case,” she told my parents. “Possibly several. Against the nurse personally and the district.”

My dad nodded once.

“Good,” he said. “Because I’m not letting this disappear.”

The school had paper trails. They always did.

They had my medical action plan signed by my parents, my doctor, the principal—and Nurse Brennan herself—stating in clear language that I could self-administer epinephrine at any time.

They had backup EpiPens in the nurse’s office.

They had my medical alert bracelet documented.

They had everything they needed.

And Nurse Brennan still decided her authority mattered more.

Security footage showed me stumbling in. Holding my throat. Clearly in distress.

It showed the minutes passing.

It showed Mr. Kaplan walking by, stopping, looking through the window, and instantly going from annoyed teacher to terrified adult.

It showed him banging on the door, pointing, yelling.

It showed Nurse Brennan opening the door and trying to wave him off.

It showed him pushing past her anyway, dialing 911 with shaking hands.

It showed her protesting while he saved me.

When my mom watched the footage, she couldn’t make it through. She left the room, shaking, because seeing your child collapse on a screen does something to a parent that no apology can undo.

My dad watched it all without blinking.

Afterward he said, softly, like he was speaking to himself, “She sat there.”

Amanda filed complaints. Reports. Requests. Everything that turned a private nightmare into a public problem.

Two weeks later, Nurse Brennan was placed on leave. Her license was suspended pending investigation.

Someone leaked the story to local media.

And then my near-death became a headline.

A big, ugly, clickable American headline—one of those that makes parents stop scrolling and grab their kids’ backpacks a little tighter the next morning.

A student denied emergency allergy medication. A nurse refused access. A teenager hospitalized.

Parents were furious. The school board called emergency meetings. People demanded answers. Other families started talking. Stories stacked up like kindling.

The district tried to contain it.

But this wasn’t something you contained with a press release.

The more the story spread, the more the country recognized the pattern: institutions acting like rules were more important than kids, and adults dismissing teenagers until it was almost too late.

My parents did interviews.

My mom cried on camera, voice cracking when she described getting the call and imagining me alone, unable to breathe.

Dr. Foster spoke on-record about how close it was, careful with his words but clear enough that nobody could spin it into “overreaction.”

Mr. Kaplan—still shaken—told reporters he’d never forget looking through that window.

And the public response turned brutal, fast.

Because America loves a villain when the villain wears a badge and says “policy” while a child is in danger.

The legal process moved in parallel with the public storm.

There were hearings. Depositions. Evidence. Experts.

In civil court, the district’s lawyers tried to settle early. Money, apologies, quiet terms.

My dad refused the easy exit.

“This isn’t about a check,” he said. “This is about making sure the next kid doesn’t end up on a cot with their airway closing while someone argues policy.”

In the end, the case forced changes.

Not just for me, but for the district.

New rules that actually made sense: students with prescribed emergency meds could carry them. Backup doses were accessible. Staff training wasn’t optional. Emergency protocols weren’t treated like suggestions.

The irony was bitter.

The system changed only after it almost cost me everything.

Physically, I recovered. My throat healed. The swelling stopped. I went home from the hospital exhausted, shaken, alive.

But my brain didn’t get the memo that it was over.

For weeks, I woke up at night gasping, hand scrambling toward the nightstand where I kept an extra EpiPen now, because one didn’t feel like enough anymore.

Any itch made my heart jolt.

Any tightness in my throat—dry air, nerves, a cold—sent my mind spiraling back to that beige room and that clicking cabinet lock.

Dr. Foster referred me to a therapist who understood medical trauma.

She didn’t tell me to “get over it.”

She told me the truth.

“You trusted the system to protect you,” she said. “And it failed you. Your fear makes sense.”

The fear did make sense.

Because the scariest part wasn’t the allergy.

The scariest part was learning that the person assigned to help you could look at your crisis and decide it was inconvenience.

Months later, when a national program reached out about doing a segment on school medical negligence—about kids with asthma, diabetes, seizures, allergies, all depending on adults who sometimes didn’t listen—my first instinct was to say no.

I didn’t want my face attached to the worst day of my life.

But then I thought about the next kid.

The one whose parent hadn’t filled out the paperwork perfectly. The one who didn’t have a teacher like Mr. Kaplan walking by at exactly the right moment.

So I did it.

I sat under studio lights and told the story as calmly as I could. I held up my bracelet. I demonstrated how to use an EpiPen, because it mattered that people saw how simple it was—how fast a life could be saved when someone just acted.

The segment went everywhere.

Parents commented. Survivors shared their own stories. Nurses and teachers argued in threads. School districts issued statements. Legislators made speeches.

It was messy and loud and painfully American: tragedy turned into content, content turned into outrage, outrage turned into change.

A year after it happened, my family used part of the settlement to start a small foundation focused on emergency medical access in schools—helping families get medical alert bracelets, funding training, pushing for clearer policies that didn’t trap kids behind locked cabinets.

It didn’t erase what happened.

Nothing erases the sensation of your own throat closing while someone tells you to take deep breaths.

But it gave the story a shape that wasn’t just horror.

It gave it teeth.

I went back to school. Different building. Different routines. Teachers informed. Backup plans everywhere. I carried two EpiPens now, not because doctors told me to, but because my trust had been broken and redundancy felt like control.

Graduation came two years later, a hot day with rows of folding chairs and parents holding phones high to capture proof their kids made it.

After the ceremony, Mr. Kaplan found me near the edge of the crowd.

He looked older than I remembered. Not in years—just in weight, like that day had settled into his bones too.

“I think about it a lot,” he admitted. “How close it was.”

“But you were there,” I said. My voice was steady, but my hands were cold. “You saw me.”

He shook his head.

“You got yourself to that office,” he said. “You did what you were supposed to do. I just made sure someone with sense got to you in time.”

We stood there for a moment in the noise and celebration, bound together by a day that should have ended differently.

Then he said something simple.

“I’m proud of you.”

Not for being a headline. Not for being a case file.

For turning survival into something that might keep another kid alive.

That was the only “happy ending” that felt real.

Because the truth is, I didn’t nearly lose my life because allergies exist.

I nearly lost it because an adult in a position of power decided the rules mattered more than the reality in front of her.

And in America—where schools love policies, and districts love liability language, and “we’ll look into it” is often the first line of defense—that lesson is the one that sticks.

If a kid tells you they can’t breathe, believe them.

If someone has emergency medication, don’t lock it away.

If minutes matter, don’t waste them proving you’re in charge.

I walked into the nurse’s office that day thinking the bracelet on my wrist and the EpiPen in my backpack were enough.

I walked out of the hospital knowing something harsher:

Sometimes, the difference between life and catastrophe is not your preparation.

It’s whether the adult in the room chooses compassion over control.

And I got lucky—because a chemistry teacher looked through a window at the right moment.

Lucky isn’t a policy.

Lucky isn’t a protocol.

Lucky isn’t something any parent should have to rely on.

So I stopped relying on it.

And I made sure the whole country heard why.

The first time I walked back onto campus after County General, the school looked exactly the same.

Same brick facade. Same fluttering banners that said WE ARE LINCOLN and LEARN TODAY, LEAD TOMORROW. Same row of pickup trucks and minivans crawling through the drop-off loop like nothing had happened.

But my body didn’t see the building the way it used to.

My body saw a trap.

It saw beige hallways and fluorescent lights and doors that didn’t open fast enough. It saw a glass cabinet with a lock. It saw a cot in the corner of a room that smelled like antiseptic and stale coffee. It saw a clipboard in Nurse Brennan’s hand while my throat swelled shut.

My parents didn’t let me come back alone.

For the first week, my dad drove me himself, parked right in front of the main office like he was daring someone to say something about visitor policy. He walked me in, shoulder-to-shoulder, a man who had discovered just how thin the line was between “fine” and “funeral,” and who now refused to let the school pretend it was a misunderstanding.

The administration had moved fast, at least on the surface. There were new laminated posters in the hallways about “Emergency Response Procedures.” The principal had sent a district-wide email about “reinforced medical protocols.” Teachers had been instructed to review student emergency plans.

It all looked very official. Very American. Very “we take this seriously.”

But none of it erased the fact that, in that same building, I had stopped breathing.

And the worst part was that everyone knew.

When I stepped into first period, the room went quiet in a way that made my skin crawl. Kids stared like I was a ghost who’d wandered back in. Someone whispered, “That’s him,” like I was a documentary subject.

A girl in the front row did that wide-eyed sympathetic look people do when they don’t know what to say.

A guy in the back muttered, “Dude, I thought you died.”

I sat down slowly, feeling every gaze like a weight. I wanted to yell, Yes, I almost did. I wanted to scream that it wasn’t a rumor or a dramatic story or “that crazy thing that happened last month.” It was my lungs. My heart. My life.

Instead I kept my head down and opened my notebook like I was just another student.

That was the first lesson of going back: the world keeps moving, even when yours almost ended.

At lunch, the cafeteria noise hit me like a wave. Trays clattering, chairs scraping, kids yelling across tables. The smell of fried food and sugary drinks and whatever mystery seasoning they used that week.

I hadn’t realized how much smell mattered until the reaction. Now every scent felt like a possible threat. Peanut butter from someone’s sandwich. Granola bars. Trail mix. Cookies. The hidden land mines of a normal American lunch.

My mom had packed my food in sealed containers like she was sending supplies into a disaster zone. I found an empty corner table and ate slowly, scanning the room the way prey scans for predators.

It wasn’t the kids I feared.

It was the idea of another adult deciding I was being dramatic.

My phone buzzed. A text from my mom.

You okay? Tell me if you feel even a little weird.

I typed back: Fine.

I wasn’t fine.

Not really.

My throat still felt wrong sometimes, even though Dr. Foster said the tissue would heal completely. I kept swallowing, checking, like I could feel the memory of swelling there.

And the anxiety didn’t sit in my mind like normal worry. It sat in my body like an alarm system that wouldn’t shut off.

Two days after I returned, the school called my parents in for what they described as a “medical safety meeting.”

They scheduled it like it was routine, like it was something they did all the time.

My dad laughed when he read the email.

“Sure,” he said. “Let’s see what they have to say.”

The meeting was in the conference room near the front office. Big oval table. Tiny American flags on a shelf. A framed “Mission Statement” poster about “Excellence” and “Character.”

Principal Whitman sat at one end. A district administrator sat beside him, a woman with perfect hair and a folder thicker than my chemistry textbook. Two other people were there: an interim nurse they’d brought in and the school counselor, who looked like she’d rather be anywhere else.

Nurse Brennan wasn’t there.

She was “on administrative leave pending investigation,” which was the district’s polite way of saying, We’re hoping this dies down before we have to admit anything.

Amanda Cho joined the meeting via speakerphone. My parents didn’t go anywhere without her now. Not because they needed someone to tell them what was right, but because they were done letting the school control the narrative.

Principal Whitman started with the same tone he’d used at the hospital: careful concern mixed with self-protection.

“We want to emphasize how sorry we are for what happened,” he said. “Student safety is our top priority.”

My dad leaned back in his chair.

“If it was your top priority,” he said evenly, “my son wouldn’t have stopped breathing in your nurse’s office.”

Silence.

The district administrator cleared her throat.

“We’ve reviewed the incident,” she said, like she was talking about a broken vending machine. “And we’re implementing procedural improvements.”

Amanda’s voice came through the speakerphone, sharp and calm.

“Procedural improvements don’t answer why a nurse violated a signed medical action plan,” she said. “And they don’t answer why the district’s policies allowed her to lock away a student’s emergency medication in the first place.”

The administrator’s smile tightened.

“We’re not admitting any wrongdoing,” she said. “But we are reviewing policy language to ensure clarity.”

My mom’s hands were folded on the table so tightly her knuckles were white.

“Clarity?” she said. “My son’s plan was clear. His bracelet was clear. His symptoms were clear. Your nurse chose to ignore it.”

The interim nurse spoke up then. She was younger, maybe late twenties, and she looked nervous but sincere.

“For what it’s worth,” she said quietly, “in every district I’ve worked in, students with severe allergies are allowed to self-carry their EpiPens. Locking them away creates a delay risk.”

My dad’s eyes locked on the administrator.

“You hear that?” he said. “Even your replacement knows it.”

Principal Whitman tried to salvage the conversation with a sheet of paper he slid across the table.

“We’ve created a new accommodation plan,” he said. “Two lock boxes per building with combination codes known to the student and parents. Copies of emergency plans in each classroom. Staff training scheduled for next month.”

Amanda didn’t sound impressed.

“Training next month is not a solution,” she said. “And lock boxes are only effective if students have unrestricted access without staff interference.”

The administrator’s voice cooled.

“We need to balance safety with supervision,” she said. “We can’t have students administering medication unsupervised—”

My dad’s chair scraped back as he leaned forward.

“My son has been administering his own epinephrine since he was eleven,” he said. “Because when you’re choking, you don’t have time to wait for an adult to decide whether you deserve to breathe.”

That landed.

For a moment, no one had a scripted response.

The counselor tried a softer angle.

“We also want to support you emotionally,” she said, looking at me. “After a traumatic event, students sometimes experience anxiety—”

I laughed.

It came out ugly.

“Yeah,” I said hoarsely. “Crazy how almost dying makes you anxious.”

She flushed and looked down.

Amanda cut in before the district could pivot into “mental health support” as a distraction.

“Let’s be clear,” she said. “We’re pursuing a full investigation through the state nursing board and the district attorney’s office. We’re requesting all records, including Nurse Brennan’s training logs, her incident documentation, and any prior complaints. This isn’t going away with a new laminated poster.”

The meeting ended with forced politeness and no real resolution, but something shifted after that.

The district realized my parents weren’t going to be worn down by bureaucracy.

They realized they couldn’t stall until summer.

They realized this was going to become a problem they couldn’t contain inside a conference room.

And outside the building, it already had.

A local reporter started hanging around the parking lot at dismissal.

The first time I saw a camera pointed toward me, my stomach flipped. I ducked my head and tried to walk faster, but the reporter called out anyway.

“Hey! Are you the student?”

My dad stepped between us like a wall.

“No comments,” he said. “Talk to our attorney.”

The reporter didn’t back off.

“Parents are saying this isn’t the first time Nurse Brennan ignored a medical situation,” she called. “Have you heard that?”

My mom’s face tightened.

“We have heard plenty,” she said. “And we will be addressing it.”

The next night, the story aired on the local news.

My face blurred. My name not said. But anyone who knew us knew it was me.

The segment showed an exterior shot of Lincoln High. Dramatic music. A headline graphic: STUDENT HOSPITALIZED AFTER NURSE REFUSES EPI PEN.

They interviewed a “concerned parent” in the parking lot, a woman who said her son had asthma and she was terrified.

They interviewed a district spokesperson who said the district “takes all allegations seriously” and was “reviewing procedures.”

Then they interviewed Dr. Foster.

He didn’t say my name. He didn’t have to. His words hit like a hammer.

“In anaphylaxis, epinephrine is the first-line treatment,” he said. “Delaying it can lead to respiratory arrest. Minutes matter.”

That phrase—minutes matter—was in every piece of coverage after that.

It became the hook.

The line people repeated.

The thing that made the story simple enough for strangers to feel rage about.

Online, the comments exploded.

Some people were compassionate. Parents of kids with allergies wrote long paragraphs about fear and medical plans and how they’d been dismissed too.

Some people were cruel. That’s America too. “Kids these days are dramatic.” “Sue-happy parents.” “Maybe he was faking.” Those comments made my dad’s jaw clench like he was biting down on the urge to hunt strangers through the screen.

Then the other stories started surfacing.

It began with an email to Amanda from another family. A woman whose daughter was diabetic.

She said Nurse Brennan had refused to allow her daughter to check her blood sugar because “she didn’t look low.”

When the girl’s blood sugar crashed in gym class, she fainted. The parents had complained. The complaint disappeared into the district’s void.

Then a father called. His son had asthma.

He said Nurse Brennan had denied his son an inhaler because “he’d used it too much this week already,” like an inhaler was a privilege.

The kid had ended up in the ER anyway.

More families came forward, emboldened by the attention, the outrage, the chance that this time—this time—someone might listen.

Amanda started keeping a spreadsheet. Names. Dates. Complaints. Evidence.

It stopped being just my story.

It became a pattern.

And patterns are harder to dismiss as “one unfortunate incident.”

The district attorney’s office got involved faster than anyone expected.

Six weeks after my reaction, my parents got a call from Amanda.

“They’re filing criminal charges,” she said.

My mom went silent on the other end of the phone, like her brain couldn’t fit the words into reality.

My dad asked, “Against who?”

“Against Nurse Brennan,” Amanda said. “Reckless endangerment, negligence, failure to provide medical care. They’re going after her.”

My dad exhaled slowly.

“Good,” he said. “Because she almost killed my son.”

Hearing it spoken like that—almost killed—still made me nauseous. It was too direct. Too real. But it was true.

The arraignment was quick. My parents attended. I didn’t.

I couldn’t.

The idea of seeing her face again made my throat feel tight even though it was just memory.

Amanda described it afterward in her office.

“Nurse Brennan pleaded not guilty,” she said, flipping through her notes. “Her attorney claims she used professional judgment.”

My dad’s laugh was humorless.

“Professional judgment,” he repeated. “She locked the medication away.”

Amanda nodded.

“The judge set bail. Preliminary hearing scheduled.”

In the civil case, the district tried harder to settle once criminal charges were filed. They wanted it quiet now. A big check and a confidentiality agreement. The kind of agreement districts love because it turns public failure into private paperwork.

My dad refused to sign anything that would keep the story from being told.

Amanda negotiated anyway, not because my parents wanted money, but because money forced policy changes. Money forced districts to act in a way they never acted out of conscience alone.

Eventually the case moved toward trial.

And that’s when the district’s defensive politeness turned into something uglier.

They started whispering about responsibility.

They started hinting that maybe I hadn’t communicated well. Maybe I should have alerted a teacher sooner. Maybe it wasn’t clear I was in danger.

Amanda shut that down so fast it almost felt like mercy.

“If they try to blame you,” she told me in her office, “remember this: you did exactly what you were trained to do. You sought help. You requested your authorized medication. An adult denied you. That’s the story. Don’t let them make you defend your own survival.”

Still, the fear sat in my stomach like a stone.

Because part of being a teenager in an American institution is knowing that adults will rewrite the story if it protects them.

Trial week arrived like a storm cloud.

I had never been inside a courtroom before, not like this. Not as a reason everyone was there.

The courthouse smelled like old paper and cold air conditioning. The American flag stood in the corner like it had an opinion on everything.

Nurse Brennan sat at the defense table wearing a conservative blazer, hair neat, face composed.

She looked like someone who still believed she was the victim of an overreaction.

When she glanced toward my family, her eyes didn’t show guilt.

They showed irritation.

Like we were still interrupting her coffee break.

The civil trial moved fast. Evidence stacked up like bricks.

Amanda presented my medical action plan. Enlarged on a screen so the jury could read it.

AUTHORIZED TO SELF-ADMINISTER EPINEPHRINE AT ANY TIME.

She pointed to Nurse Brennan’s signature.

She presented my medical history, the documented reactions, the doctor’s warnings.

She played the security footage.

The jurors watched me stumble in, clutching my throat. They watched time pass. They watched Mr. Kaplan stop, look, react with horror. They watched him force his way in and call 911.

Some jurors flinched when my body collapsed on the cot.

My mom gripped my hand so hard it hurt.

Then Amanda called witnesses.

Dr. Foster testified in a calm, steady voice, explaining anaphylaxis with clinical clarity that left no room for “panic attack” excuses.

Thomas Irving, the paramedic, described arriving and finding me blue, unresponsive. He described forcing open the cabinet. He described the nurse trying to minimize it even then.

When Amanda called Mr. Kaplan, he looked like he’d aged ten years since that day.

On the stand, he admitted he’d initially been annoyed when I left class.

“I thought he was trying to get out of a quiz,” he said.

Then he swallowed hard.

“And then I looked through the window.”

His voice broke slightly.

“I saw him on the cot,” he said. “And she was at her desk. Writing. Like it was… nothing.”

The courtroom went still. Even the defense looked uncomfortable for a moment, because that image was impossible to spin.

Then Nurse Brennan took the stand.

She swore to tell the truth.

And she proceeded to tell the version of the truth she’d already written in her incident report: that I appeared anxious, dramatic, hyperventilating; that she assessed hives and believed it was mild; that she administered Benadryl; that she believed epinephrine was unnecessary.

Amanda’s cross-examination was surgical.

“You documented a blood pressure of eighty over forty,” she said.

“Yes,” Nurse Brennan admitted.

“And a heart rate of one-forty.”

“Yes.”

“And you were trained that those vital signs indicate severe distress.”

“They can indicate distress,” Nurse Brennan said carefully.

Amanda leaned in.

“Distress like shock,” she said. “Distress like a body failing. Distress like a child dying. Correct?”

Nurse Brennan hesitated.

“In some cases,” she said.

“In this case,” Amanda said, voice steady, “did you believe those vital signs were normal?”

“No,” Nurse Brennan whispered.

“Did you call 911?”

No.

“Did you administer epinephrine?”

No.

“Did you unlock the cabinet and allow him access to the medication his doctor authorized him to self-administer?”

Silence.

The judge looked over his glasses.

“Answer,” he said.

“No,” Nurse Brennan said.

Amanda let the word hang in the air, heavy and final.

That “no” was the whole case.

The jury deliberated for hours, but it didn’t feel like it could have gone any other way.

When they returned, their faces were set.

They found in our favor.

Damages. Policy changes. Public acknowledgment. Nurse Brennan personally liable.

In the hallway afterward, the district’s attorney approached Amanda with a tight smile.

“We’re going to appeal,” he said.

Amanda’s smile was colder.

“You’re welcome to,” she said. “But the footage isn’t going away.”

Neither was the criminal case.

If the civil trial was about responsibility, the criminal trial was about recklessness.

It was the state saying: you don’t get to hide behind “policy” when a kid is dying.

That trial was uglier.

Because now Nurse Brennan wasn’t just fighting for her reputation—she was fighting for her freedom.

Her attorney painted her as a dedicated nurse caught in an impossible situation. They implied she’d been overwhelmed. That she’d made a mistake.

The prosecutor didn’t argue that she’d wanted me dead.

He argued something more chilling: that she had known I was in danger and still chose control over action.

That she had watched minutes pass and did nothing.

That her arrogance was reckless.

Witness after witness repeated the same core truth: the signs of anaphylaxis were there. The documented plan was there. The medication was there. She still delayed.

The jury convicted her.

When the judge sentenced her, he didn’t mince words.

“You were entrusted with children’s safety,” he said. “You had every resource to save a life, and you chose not to.”

Nurse Brennan stood stiff, jaw tight, face flushed with anger rather than shame.

When the deputies led her away, handcuffs clicking, my mom cried again.

My dad didn’t.

He just stared, expression hard, like he was watching a chapter close but not feeling relief.

I expected it to feel like victory.

But in the weeks after, I learned something no courtroom drama on TV really shows:

Justice doesn’t rewind time.

It doesn’t erase the memory of choking.

It doesn’t stop your body from flinching when a door clicks shut.

It doesn’t quiet the part of your brain that whispers, What if next time there isn’t a teacher walking by?

The district rolled out its changes.

Lock boxes. Training seminars. Emergency response drills. Teachers signing forms that said they’d reviewed medical plans. Emails and announcements and meetings.

On paper, the school became safer.

In my body, the school remained a place where I had nearly disappeared.

I went to therapy every week.

Dr. Ruiz explained the mechanics of trauma, how the body stores it, how triggers can be tiny and stupid and unavoidable.

She taught me breathing exercises, which felt ironic—breathing exercises after the day I couldn’t breathe.

She helped me name the anger.

“You’re angry because you were betrayed,” she said. “You did everything right. And the person responsible didn’t.”

Some sessions I talked about nightmares.

Other sessions I talked about the humiliation of being treated like I was faking.

Some sessions I just sat there with my fists clenched, because words felt too small.

Slowly, I stopped waking up gasping every night.

Slowly, my throat stopped feeling haunted.

But I didn’t go back to the kid I was before.

That kid trusted adults in authority.

This version of me didn’t.

One afternoon, about six months after the incident, I got an email from a producer at a national news program.

They were doing a segment on school medical negligence across the U.S. Stories about asthma attacks ignored, diabetic episodes dismissed, seizures minimized.

They wanted a survivor.

A face.

A voice.

My first instinct was to delete it.

I didn’t want to be a headline again. I didn’t want strangers commenting on whether I “really” needed an EpiPen. I didn’t want to relive it under bright studio lights.

But my mom read the email over my shoulder and went quiet.

“Do you want to?” she asked softly.

My dad didn’t say anything at first. Then he said, “If you tell it, they can’t bury it.”

That’s what it came down to.

Not revenge.

Not attention.

Refusing to let the story be buried under district press releases and legal language.

So I said yes.

The interview was in a small studio in a city a few hours away. The kind of place with makeup artists and lighting rigs and producers with headsets.

They asked me to bring my medical alert bracelet.

They asked me to demonstrate an EpiPen.

They asked me to describe what it felt like to not be believed.

That last one was harder than describing the swelling.

Because the swelling was physical. The disbelief was personal.

I looked straight into the camera and told the country what I wished someone had said in that nurse’s office:

“If a kid with a documented condition tells you they need emergency medication, believe them. Don’t make them prove they’re dying.”

The segment aired. It went viral. Millions of views.

And then the messages started pouring in.

Parents. Teachers. Nurses. Kids with allergies. Kids with asthma. Adults who had grown up with chronic conditions and still remembered being dismissed.

Some messages were heartbreaking. Some were furious. Some were grateful.

It felt strange, being turned into a symbol.

But it also felt like the story had grown bigger than my fear.

My parents used the settlement money to start a foundation. It wasn’t huge at first. Just enough to fund medical alert bracelets for families who couldn’t afford them, enough to sponsor training sessions, enough to pay for advocacy work in our state.

They named it after my dad—not because he wanted his name on anything, but because it made the foundation sound official, like something legislators couldn’t ignore.

We started meeting families.

A mom whose son carried an EpiPen in a zippered pocket like mine.

A dad whose daughter had asthma and kept getting told to “tough it out.”

A teenager who wore a bracelet and looked at me like I was proof you could survive and still matter.

The work didn’t feel glamorous.

It felt necessary.

Because in every story, the villain wasn’t the allergy or the asthma or the diabetes.

It was the same thing: an adult with power deciding a kid was exaggerating.

A year passed.

Then two.

I graduated.

Standing in my cap and gown, I looked out at the sea of faces and tried to feel normal.

My throat worked. My lungs worked. My heart worked.

I was alive.

After the ceremony, when the crowd spilled out into the heat, Mr. Kaplan found me again.

He looked less haunted than he had at trial, but the memory still lived behind his eyes.

“I still think about it,” he said.

“I know,” I replied.

He hesitated, then asked, “Are you… okay now? Really?”

I wanted to say yes, because yes is easier.

Instead I said the truth.

“I’m better,” I said. “But I don’t think I’ll ever forget what it felt like to not be believed.”

He nodded slowly, like he understood more than words could cover.

“I’m sorry,” he said. “Not for what I did. For what you went through.”

“It’s not your fault,” I said.

“I know,” he said. “But it’s still wrong.”

That was the strange gift of the whole ordeal: I learned who would act, and who would hide behind rules.

Mr. Kaplan acted.

My parents acted.

Amanda acted.

Dr. Foster acted.

The paramedics acted.

And Nurse Brennan—who had been entrusted with a key to a cabinet that held my life—chose not to.

She served her sentence. She lost her license permanently. She disappeared from healthcare and from schools.

But she never disappeared from my memory.

Sometimes, years later, I still hear the click of a lock and feel my throat tighten for a second.

Then I breathe.

Deep, steady breaths—not because someone told me to, not because it’s “policy,” but because I can.

Because I got lucky.

And because I refused to let luck be the only thing standing between kids like me and the next locked cabinet.

News

At my bloodwork appointment, the doctor froze. Her hands were trembling. She took me aside and said, “You must leave now. Don’t tell him.” I asked, “What’s going on?” She whispered, “Just look. You’ll understand in a second.” What I saw on the screen—true story—destroyed everything.

The first time I realized something was wrong, it wasn’t the nausea or the hair in the shower drain—it was…

The mafia boss’s baby was losing weight steadily—until a nurse spotted what the doctors missed.

The first time Damian Castellano begged, it wasn’t on his knees, and it wasn’t with tears. It was with a…

“You’re so awkward you make everyone uncomfortable. Don’t come.” Dad banned me from the wedding, saying I’d embarrass my sister’s rich groom. So I went back to Area 51 on the wedding day. The next day, walking the base, I opened Facebook—and froze at what I saw.

The first time my phone detonated with missed calls, the Nevada sun was bleaching the world white, and I was…

“Your daughter doesn’t deserve a sweet sixteen,” my mom said. “Not after what she did to your niece.” My daughter had refused to give her new laptop to my sister’s kid. I said nothing. I canceled the party I’d planned—a $34,000 budget. Instead, I flew just my daughter to Paris for her birthday. We posted one photo. Within an hour, my sister was commenting, “We need to talk!”

The first time my mother said it out loud, it sounded like a line from a courtroom drama—calm, final, like…

My sister deliberately spilled red wine on my dress right as my wedding ceremony began. All the guests fell silent, yet my parents stood up and clapped. I stayed calm, smiled, and whispered, “You’ll regret this.” Two weeks later…

The first thing people noticed wasn’t my face. It wasn’t the gasp that rippled through the pews like a wave,…

I walked across the graduation stage alone while my parents hosted a Super Bowl party. I cried in the parking lot, then booked a one-way ticket that changed my life forever…

The first thing I remember is the sound of jet engines vibrating through the floor beneath my feet, a low,…

End of content

No more pages to load