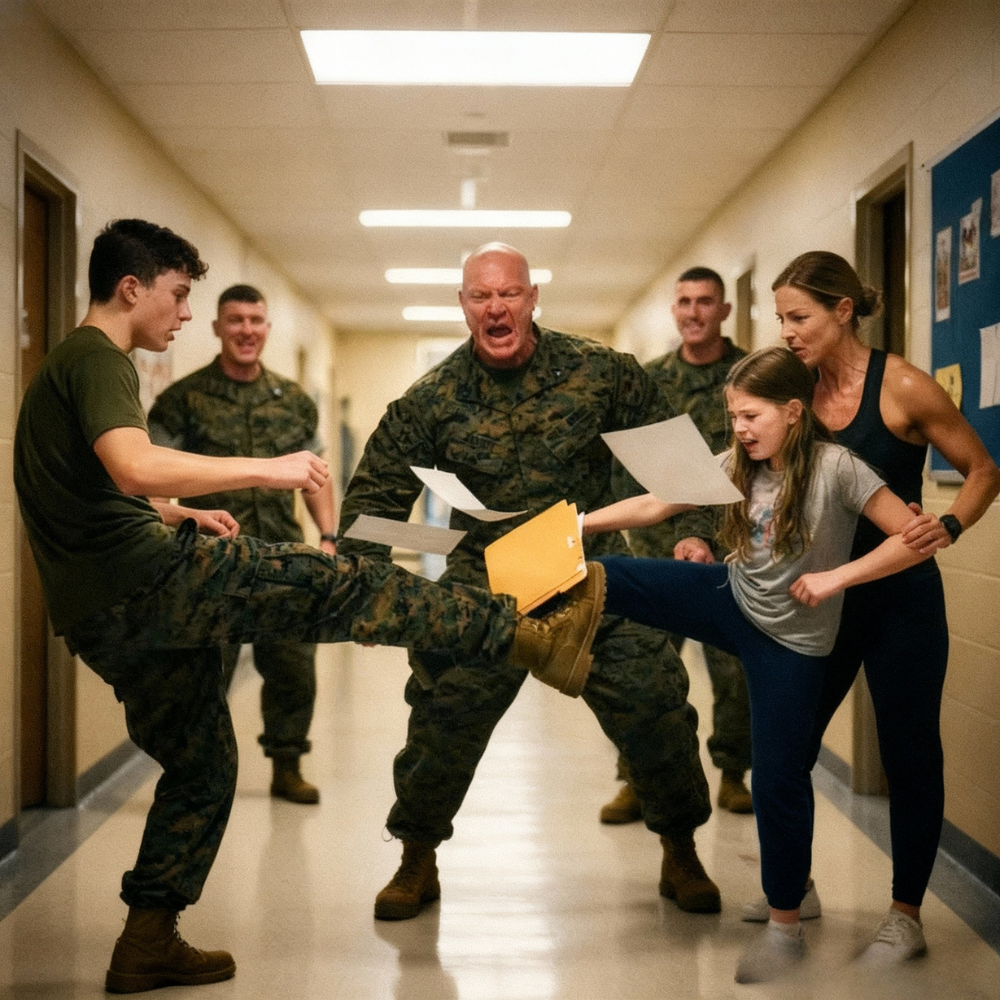

They thought no one was watching when the kid’s shin took the hit. Just a quick, calculated tap of a sneaker against bone in a quiet American hallway, under a buzzing strip of fluorescent light and a faded poster about kindness peeling at the corners. There was no camera angle, no dramatic soundtrack, just a twelve-year-old girl on the tile floor of a California middle school, clutching a bent folder while four adults in Marine Corps base IDs laughed like it was all a joke. Out by the street, the Stars and Stripes fluttered on a rusted flagpole above a parking lot full of pickup trucks and SUVs. Inside, in a hallway that suddenly felt too long and too empty, someone decided she was an easy target. Someone else decided to kick her for telling the truth. And the woman they said didn’t exist was still ten steps away from the door.

But we’ll get there.

First, picture the multipurpose room of Redwood Community School, thirty minutes north of downtown San Diego, public school brick and beige paint, the kind of place where bake sales and budget cuts take turns running the show. The ceiling panels are stained with old leaks from years when the district couldn’t afford to fix the roof. Rectangular fluorescent lights hum overhead like tired bees. Plastic folding chairs fill the room in uneven rows, their metal legs scratching the linoleum when anybody shifts in their seat. At the far wall, a hand-lettered banner reads “QUARTERLY PROGRESS NIGHT” in marker colors that don’t quite match the school’s official red and white.

It’s 6:07 p.m. on a Tuesday. Somebody in the back is still wrestling with the Costco coffee urn. Lukewarm lemonade sits in a clear plastic dispenser, sweating condensation into a paper tablecloth decorated with tiny American flags left over from a Memorial Day event. Parents stream in, smelling faintly of fast food, hand sanitizer, and the kind of fatigue that comes from working all day and then driving across three freeway exits in traffic to sit in a folding chair and listen to a teacher explain grade reports.

Mia Calder sits in the far left corner of the room, near the wall, where she can see both the door and the table of refreshments. She’s twelve, small for her age, with dark hair braided down her back so tightly not a single strand escapes. Her sneakers are clean but starting to show the faded gray of too many playground days. Her jeans are rolled once at the ankle. Her jacket is zipped up even though the room is a little warm. In her lap rests a blue folder, its edges already softened from being carried in her backpack all week. She holds it flat against her thighs, fingers spread along the bottom edge as if she’s afraid the folder might float away if she loosens her grip.

Every few seconds, her eyes flick toward the door.

Once.

Twice.

Again.

No sign of her mom yet.

Her stomach feels strange, heavy in a way that has nothing to do with food. She’d only picked at her school lunch that day—a rectangle of pizza, canned peaches, milk in a carton—but the emptiness is crowded out by something else. Not dread, exactly. Not fear. More like pressure from every direction at once, like she’s standing in the deep end of a swimming pool, lungs full, ears ringing, and she has to hold on just a little longer.

Around her, other kids are basking in the simple glow of being seen. A girl in a sparkly headband leans forward in her seat, whispering proudly to her friend, “My dad flew back from Virginia just for this. He’s only home for four days.” At another table, a boy gestures toward a man in a perfectly pressed Marine Corps camo uniform who is shaking hands with the principal like they’re equals. The man’s boots are polished so well they catch the overhead light. His little son is practically vibrating with pride.

Everywhere Mia looks, somebody has somebody.

She has a folder.

At a table near the center right of the room, four adults sit like they own the air around them. Two are Marine dads, big-shouldered men in polo shirts and jeans, their short haircuts and squared jaws announcing “military” before their voices even enter the scene. Even out of uniform, their belts hold clipped-on base ID badges and keys that jingle softly when they move. With them sit their wives—one in large hoop earrings and a cardigan with tiny silver stars along the sleeves, the other in a sleeveless top that shows off a tan line from afternoons at the base’s pool. Their teenage kids hover nearby: a boy with a fresh haircut and a phone never far from his hand, and a girl in high-waisted jeans, eyeliner just a shade too dark for middle school but exactly right for TikTok.

They are louder than everyone else. Not shouting, just broadcasting. Their stories about deployment rotations, base housing complaints, and last year’s PTA “disaster” roll across the room and bounce off the coffee urn. They laugh at things that aren’t actually funny, the kind of practiced social laughter that draws attention even when the comments themselves could have stayed private.

One of the Marine wives glances around and spots Mia sitting alone in the corner.

“Looks like somebody got stood up again,” she mutters, just loud enough.

The Marine dad next to her snorts. “Or maybe her mom’s still stuck in traffic from whatever imaginary place she drives in from.”

The others chuckle. It isn’t a big moment. Nobody throws anything. Nobody screams. But the words land like small stones, clinking against the armor Mia is trying to wear on the inside. She doesn’t turn her head. She doesn’t flinch. Her fingers just tighten around the edge of the folder until the laminated surface squeaks softly under her nails.

At the front of the room, Ms. Caffrey claps her hands together, trying to pull focus. She’s the kind of teacher who is always a little overwhelmed and always trying anyway. Her blazer is slightly too large, her glasses slide down her nose when she nods, and her arms are full of papers she keeps shuffling like they might rearrange themselves into a better plan.

“Okay, parents, if we could all take our seats,” she calls out, forcing brightness into her voice. “We’re going to get started with our quarterly progress check-in. Thank you all for being here. Students, you’re very brave—this isn’t exactly the most exciting evening, I know.”

Laughter ripples politely.

Mia sits up straighter in her chair.

Her mom is late, but late isn’t the same as missing. Her mom knows how much this night mattered to her. They’d circled the date on a wall calendar at home three weeks ago. Her mom had teased her about the serious way she’d drawn the circle, saying, “You’re starting to sound like my commanding officer,” and Mia had smiled in spite of herself. They’d talked about how they would celebrate afterward, maybe by picking up burgers and milkshakes or going to the twenty-four-hour diner near the base gate where the servers never asked too many questions and always called everyone “hon.”

Her mom said she’d be here. So she will be here.

Mia grips that thought like a lifeline.

Ms. Caffrey tries to warm up the room with something she read in a professional development seminar about community building. “To start tonight,” she says, “we’re going to do something a little different. When I call your name, I’d like each student to stand, say your name, and introduce the parent or guardian you brought with you. Just so we can all put faces to names. We’re a team, right? We’re all in this together.”

It sounds good in theory. In practice, it’s a roll call of who is loved and visible.

One by one, kids stand up.

“I’m Ava, and this is my mom. She’s the PTA vice chair.”

“I’m Malik. My dad’s back from deployment, Sergeant Ford.” Applause and a couple of whistles follow that one, the kind of reflexive appreciation American schools are trained to give any mention of the military.

“I’m Nolan. My parents are in the back by the coffee. They brought cookies.”

Parents clap. Some wave. There are phone flashes as people snap pictures, little moments saved for relatives and Instagram stories.

Then Ms. Caffrey looks toward the far left corner.

“Mia? Do you want to go ahead?”

Mia stands up slowly, her folder still clutched in one hand, knuckles white against the blue plastic. The front edge of her chair scrapes softly backward. For a second she thinks her voice might vanish, but when she finds it, it’s steady. Not loud, but clean. She doesn’t look at anybody’s eyes, just at a spot on the opposite wall.

“My name is Mia Calder,” she says. “My mom’s running late. She’s a Navy SEAL.”

The room goes silent.

It’s not the respectful, awed silence that greets a big announcement at a graduation ceremony. This silence feels like a held breath that nobody wants to claim. It lasts a beat too long. Then it shifts, like air in a room right before a storm.

At the Marines’ table, Marine dad number one chuckles into his sleeve.

Marine mom with the silver-star cardigan snorts softly.

Ms. Caffrey blinks, her smile flickering with uncertainty. “Oh! Well, I’m sure she’ll be here as soon as she can,” she says, voice a little too bright. “Thank you, Mia.”

But the comment has already left the starting line, sprinting around the room.

“Wait,” another dad mutters to his neighbor. “Did she say SEAL?”

The Marine wife with the hoop earrings raises her eyebrows high. “Sweetheart,” she calls out, not bothering to lower her voice. “SEALs don’t do PTA night. Sorry.”

The Marine dad beside her laughs louder, emboldened. “She’s been watching movies. Next she’ll say her mom parachuted onto the roof.”

They laugh again. Small laughs, but sharp.

Mia lowers herself back into her chair, a controlled descent. She doesn’t defend herself. She doesn’t repeat what she said. Her heart is beating so fast it feels like it might bruise her ribs from the inside, but she keeps her face neutral. She adjusts the folder in her lap, flattening it, aligning the edges with obsessive care. If she keeps her hands busy, nobody will see them shake.

“She really is,” Mia says softly, almost to the desk surface in front of her rather than the people around her. “She’s on base. She’s training today.”

Marine mom with the bracelets tilts her head, fake-sweet. “Honey, it’s okay to admit you made it up,” she says, dripping condescension.

Marine dad number two shakes his head, amused. “If there is such a thing as a female SEAL—and that’s a big if—they’re not showing up for a middle school progress night.”

A few kids around them smirk, not because they’re cruel, but because they’re air-pressure kids. They absorb whatever tone the adults around them set. The adults have decided that this is funny, so the kids decide it too.

Ms. Caffrey rushes to move things along, calling on the next student, but the damage is already done. The air around Mia feels heavier, like someone turned up the humidity in just her corner of the room. Her cheeks are hot. Her throat feels tight. She doesn’t cry—SEAL kids don’t cry in public, that’s what she tells herself, even though she’s never heard her mom actually say the phrase. But her shoulders fold inward a fraction, like her body is trying to take up less space.

She waits.

Her mom is coming. She always comes. Sometimes late. Never missing.

Ten minutes later, the meeting breaks for a stretch. Parents shuffle toward the coffee urn and lemonade; kids wander into the hallway that connects the multipurpose room to the classroom wing. The murmur of conversation spills through the open door, blending with squeaky sneaker sounds and distant locker doors slamming.

Mia slips out as quietly as she can. She walks a little too fast at first, then slows, nervous about drawing attention. Her folder is pressed flat against her chest now, hugged like armor. The hallway feels cooler than the multipurpose room, the kind of institutional cool you get from overworked air conditioning units that never quite maintain a steady temperature.

Halfway down the hall, she picks a bench beneath a faded anti-bullying poster. It shows a smiling, diverse group of cartoon kids under the phrase “KINDNESS IS OUR CULTURE” in big bubble letters, but the corners of the poster are curling up and the tape is yellowed. Someone has drawn a mustache on one of the cartoon faces in ballpoint pen. The poster feels less like a rule and more like a decoration somebody forgot to take down.

Mia sits, tucking one foot under the bench, folding herself smaller. If she doesn’t move, maybe nobody will notice her. Maybe she can just merge into the corridor, another shape in the margins.

The laughter reaches her before the group does.

It’s that same too-loud, too-confident sound from the multipurpose room, rolling down the hallway. Marine dad number one, Marine dad number two, their wives, and their teens stride out of the multipurpose room like they’re leaving a briefing. Their footsteps are heavier than they need to be. The teenage boy and girl walk slightly behind their parents, faces lit by their phones in that cold LED way that makes everyone look like they’re in a commercial.

Marine dad number one spots Mia immediately.

“There’s our storyteller,” he says, voice pitched to carry.

His wife smirks. “Still no mom. Maybe she tried to swim here from Coronado and got tired halfway,” she says, making a joke out of the fact that Naval Special Warfare training happens just down the coast, on California sand and in cold Pacific surf.

The teenage boy laughs under his breath. The joke is lazy. It still hits.

Mia stands up, planning to walk away before they can get too close, but Marine wife with the hoop earrings shifts just enough to drift into Mia’s path. It is technically an accident. Emotionally, it is not.

“Whoa there,” she says, her tone sweet on the surface, razor-lined underneath. “No need to rush off.”

Marine dad number one leans forward, his voice dropping into that half-teasing, half-testing register some adults use on kids when they want to see how far they can push. “Let’s hear it again,” he says. “Say your mom’s a SEAL. We could all use a laugh.”

Mia’s voice is barely above a whisper. “She is,” she says.

The teenage boy reaches out casually, like he’s about to tap her arm, but instead he flicks the bottom corner of her folder with two fingers. It doesn’t look like much, just a quick motion, but it’s enough. The folder slips from Mia’s grasp and tumbles to the floor. Papers fan out across the tile like white feathers. Math quizzes. A permission slip. A progress report she’s proud of, now spreading open like a wound.

“Oops,” he says, shrugging. “Clumsy.”

Mia drops to her knees immediately, scooping up the scattered pages with small, hurried movements. She doesn’t ask for help. She doesn’t look up. Her eyes are fixed on the paper with her science grade, now creased down the center. She tries to smooth the line with her palm, pressing hard enough that the skin of her hand blanches.

“SEALs don’t fall apart this easy,” Marine dad number one mutters, just loud enough for his little group to hear.

His wife laughs softly. “Maybe Mom’s actually supply staff,” she says. “Kids exaggerate.”

Mia gathers another paper, then another. Her hands are shaking now, just enough that she can feel it, just enough that every movement feels clumsy. The teenage girl steps closer, casting a shadow over the mess of papers.

“Say it again,” the girl demands, voice sharp. “Say your mom’s a Navy SEAL.”

“I don’t want to,” Mia whispers.

Marine dad number one crouches a little so he can look directly at her face. His eyes are amused, not kind. “Because it’s not true, kid,” he says.

“It is,” Mia insists, but it comes out so quietly that the words almost dissolve between them.

The boy shifts his foot, bumping the scattered papers with his sneaker, and then—deliberately, cleanly—moves just enough for the toe of his shoe to collide with Mia’s shin.

It is not a wild kick. It is not an accident. It is a measured, practiced, test-the-boundary impact: not hard enough to break anything, but hard enough to hurt and to send a message about power. Her shin takes the hit just above the ankle. Pain blooms fast, a hot, dull shock that spreads up her leg and claps around her knee.

Her elbow bangs the edge of a locker as she recoils. Another page slips from her fingers, drifting slowly to the floor.

She gasps. It’s a sharp, involuntary sound, somewhere between a breath and a cry. It echoes down the hallway, because the hallway is a tunnel for sound and for moments people later pretend they didn’t hear.

“If she was really a SEAL’s kid, she’d take a hit better,” Marine dad number one says, half under his breath, half not.

His wife makes a face of fake concern. “Maybe lying makes you weak,” she says.

They laugh again.

Even the teenage girl smirks now, arms folded across her chest like she’s watching a show.

Mia curls inward, pulling her injured leg closer, but she still clutches the folder against her chest with one arm. The pain in her shin throbs in pulses, like someone is tapping on the bone from the inside. Her eyes burn. She presses the edge of her sleeve to her face, once, quickly, as if that might push the stinging away.

“Stop,” she whispers. “Please stop.”

The plea doesn’t soften anything.

Marine wife steps closer, tilting her head. “Or what, Mia?” she asks. “Going to call in the SEAL teams? Is your imaginary mom going to rappel through the ceiling tiles?”

The teenage boy nudges her foot again. This time it’s not even fully a kick, just a shove, like she’s luggage in the way.

Down the hall, a student passes, eyes focused straight ahead, shoulders tight. He hears everything. He pretends he doesn’t. That’s how kids survive some schools—they learn which sounds they’re allowed to admit to hearing.

“Let’s get this on video,” the boy says suddenly, lifting his phone. The screen lights up his face with a bluish glow as he switches to camera mode. “Caption it… I don’t know… ‘When fake SEAL kids cry.’”

Mia doesn’t cover her face. She doesn’t scream. She just hunches slightly, turning her body at an angle to the phone, trying to be less visible without giving them the satisfaction of decisive flinching.

Her breath is shallow now. The pain in her leg is steady. The humiliation feels bigger, swelling in her chest like something that might crack her ribs if she lets it grow any further.

Behind them, at the far end of the hallway, the door from the parking lot opens with a soft, controlled push. No slam. No clatter. Just the slow, quiet swing of a heavy fire door that’s used to kids and teachers and janitors, not to what is about to walk through it.

Footsteps sound on the linoleum. Not stomping. Not rushing. Just a steady cadence that shifts the rhythm of the corridor without raising the volume at all.

The boy’s phone dips slightly. The teenage girl’s smile falters. She turns first, curiosity quicker than caution. Then the Marine parents follow her gaze.

Mia feels the change in the air before she looks up. It’s like the moment before a wave hits the beach, the pull of water gathering itself.

She raises her eyes.

A figure stands framed in the open doorway, the glow from the outside security lights outlining her shoulders.

Lieutenant Commander Rowan Calder is home.

She doesn’t look like the movie version of a Navy SEAL. There’s no uniform, no chestful of ribbons, no dress-white hat. Her hair is pulled back in a simple braid, still damp at the ends from a quick shower after training. She’s wearing a plain charcoal zip-front hoodie over a navy T-shirt, joggers that have seen actual work, and running shoes that look like they’ve touched more concrete and sand than treadmills. There are faint, white, almost invisible scars along her knuckles, the kind you get from impact and repetition, not from decoration.

Her eyes are the only thing about her that feels overtly dangerous at first glance. Not because they glitter or narrow or flare, but because they don’t stop moving. She scans the hallway the way other people check mirrors—automatic, constant, taking in everything without announcing that she’s doing it.

She sees her daughter first.

Not the bruise.

Not the phone.

Not the positioning of the adults.

She sees Mia on the floor against the lockers, hands clutching her folder, one knee drawn up, one sleeve damp where it has brushed her eyes.

Rowan doesn’t ask for context. She doesn’t need a PowerPoint of what happened. Her brain stitches the scene together in a fraction of a second: the papers on the floor, the red mark blooming on Mia’s shin, the angle of the boy’s body, the phone in his hand, the mocking tilt of the Marine wife’s head.

Her jaw tightens for the length of a heartbeat. Then she moves.

She doesn’t stride like she’s storming a building. She walks. Controlled. Deliberate. No wasted motion. No speed meant to show off. She closes the distance between the door and her daughter in exactly eight measured steps.

Then she crouches beside Mia, putting herself on eye level.

“Hey,” she says softly, just for her. “You okay?”

Mia nods, but her chin trembles. “They…” she starts, and the word falls apart.

Rowan lowers her voice even further, almost a whisper now. “What happened?”

“They said you weren’t real,” Mia whispers. “They said I made you up.”

Rowan’s jaw sets more firmly. She doesn’t look at the adults yet. She looks at Mia’s leg. The denim is darker over one spot on her shin where the impact bloomed. Then she sees the scattered papers and the torn edge of the folder, one corner crushed like someone stepped on it.

“Are you hurt?” she asks quietly.

“Just my leg,” Mia says, because she doesn’t have words for the rest of it. “It’s okay.”

Rowan exhales slowly through her nose. She places a hand briefly on Mia’s head, a touch more grounding than affectionate, like she is checking that her daughter is really there and not just an image she’s been staring at on a screen while deployed.

Then she stands up.

Everything that happens next happens in almost complete silence.

Rowan bends down, gathers the scattered pages with precise movements, taps them into a neat stack against her thigh. She doesn’t crumple anything. She doesn’t rip. Even in this moment, when anger presses against her ribs in slow, heavy waves, her hands are careful with her daughter’s work. She tucks the papers neatly back into the folder, straightens the bent corner as best she can, and hands it gently to Mia.

“Hold onto this for me,” she murmurs.

Then she turns.

“Which one of you,” Rowan asks, her voice level and unraised, “put hands on my daughter?”

The hallway shrinks.

The air thickens, not because she has shouted, but because everyone in the corridor suddenly realizes they have misread the entire board. The Marines straighten without thinking, backs trying to find the same posture they use in formation. Their wives instinctively move half a step behind them. The teenage boy shifts his weight from one foot to the other and tucks his phone behind his back like a first-grader hiding a forbidden toy.

Nobody answers.

Rowan doesn’t move closer yet. She doesn’t puff out her chest. Her gaze travels from face to face, taking her time, and in that quiet sweep there is more threat than any raised fist could carry.

“I asked a question,” she says again, same tone, same volume, every syllable enunciated. “Which one of you touched my daughter?”

Still, silence.

Marine dad number one finally steps forward a half pace, trying to reclaim the ground with sheer size. He’s broad, heavy in the shoulders, arms folded across his chest. His voice is steady but too polished, like he practiced sounding reasonable in mirrors.

“Look,” he says, “this is a misunderstanding. Nobody meant anything.”

Rowan tilts her head slightly, just enough to make the motion noticeable. Her eyes lock on his.

“No one meant anything?” she repeats, her tone still calm. “Then why is my daughter on the floor with a bruise on her leg and her schoolwork scattered?”

He opens his mouth, then closes it.

Marine wife with the hoop earrings jumps in with an awkward laugh. “They were teasing,” she says. “Kids roughhouse. You know how it is.”

Rowan steps forward one small step. Not enough to be aggressive. Just enough to take up the space they thought belonged to them.

“So you’re saying the bruise is accidental?” she asks.

The teenage boy blurts out, “She bumped into me,” from behind his father’s back.

Rowan doesn’t look at him yet. She crouches beside Mia again and gently lifts the cuff of her jeans. The red mark across her shin is already darkening into the beginning of a bruise, a clean horizontal bar with the faint pattern of a shoe tread.

Rowan lowers the fabric back into place and stands.

“Accidental?” she echoes. “That’s a shoe tread.”

Marine dad number one takes another half step forward, trying to regain advantage with proximity. He moves into Rowan’s personal space like he’s used to intimidating with height alone.

“You need to calm down, ma’am,” he says, using the word “ma’am” like it’s a weapon and a dismissal at the same time.

Rowan doesn’t step back. She doesn’t flinch. She just tilts her head another few degrees, studying him like she’s cataloging his choices.

“Are you trying to intimidate me?” she asks quietly.

“No one’s doing that,” he says, voice rising, volume starting to tug away from control.

“Because if you are,” she continues, still in that smooth, controlled tone, “you should stop now. You’re already behind.”

There is no flexed stance, no fists raised, no flourish. But something in the way she says those words shifts the dynamic of the hallway entirely. It’s like someone has finally turned on the correct lighting and everybody can see who actually holds authority here.

Marine dad number two steps in, flanking the first. “Lady, we didn’t know she was your kid,” he says. “We thought she was just… exaggerating.”

“You shouldn’t need to know who she belongs to,” Rowan replies. “You shouldn’t need to know anything except that she is a child at a public school in the United States of America, standing under a poster that says kindness, being mocked and kicked by adults who should know better.”

Her eyes flick down and then back up, taking in the base ID badges clipped to their belts. “You’re Marines,” she says. “Right?”

“Retired sergeant major,” Marine dad number one says quickly, puffing his chest out a fraction more. “Twenty-three years. Marine Corps.”

“Then you should know better,” Rowan says simply.

Marine mom with the hoop earrings rolls her shoulders back. “We got that you’re her mom,” she says. “But what’s your angle? You show up late, now you’re acting like you can bark orders at everyone in here. What are you, Army Reserve? National Guard?”

The remark hangs there, acidic.

Rowan’s jaw moves once, like she is adjusting something in herself and locking it down. She doesn’t rise to the bait in the exact way the woman expects. She doesn’t snap out her credentials like she’s flashing a badge in a movie.

Instead, she looks at the teenage boy.

“You kicked her,” she says.

“She bumped into me,” he repeats, voice thin now. “It wasn’t a big deal.”

Rowan’s eyes stay on him for a long, quiet second. Then she turns back to his father.

“You’re in a school hallway,” she says. “With cameras. Witnesses. A mandatory reporter at the other end of that door.” She tips her head toward the multipurpose room. “And you thought you could corner a kid and rough her up because you decided she had no one watching. That’s not a misunderstanding. That’s a calculation.”

He flushes. The boy’s shoulders hunch.

“Ma’am,” Marine dad number one starts, reaching out with one open hand like he’s going to put it on her arm and move her back a step.

He doesn’t get to complete the motion.

Rowan moves.

It’s not a Hollywood spin. There’s no flying leap, no dramatic slow-motion. Just a precise pivot of her right foot behind his, her left hand catching his wrist with practiced ease. She doesn’t yank. She doesn’t twist. She lets his own forward momentum carry him off balance. His hip slams into the locker bank with a metallic thud that ricochets down the hallway and into the multipurpose room.

Gasps spill through the open door—students, parents, anyone who hears impact instinctively reacting.

Marine wife lunges forward like she’s going to grab Rowan’s shoulder, but Rowan sidesteps with a small, clean movement, and the woman stumbles past, catching herself on the cinderblock wall.

The teenage boy steps forward now, fists balled, face flushed red. But Rowan simply shifts her weight and lifts her hand, palm outward, in a stopping motion that somehow carries more force than a shove.

“Try it,” she says quietly, her voice almost gentle.

He doesn’t.

He can’t.

Marine dad number one groans, pushing himself upright, one hand going to his ribs where the lockers kissed them. “Who are you?” he asks, genuine bewilderment seeping through the puddle of his anger.

Rowan releases his wrist with mechanical precision, as if she’s returning a tool to its exact spot on a bench. Then she takes a step back, giving him space to stand, and speaks in the same quiet tone she’s had since she walked in.

“Lieutenant Commander Rowan Calder,” she says. “United States Navy. SEAL. DEVGRU trained. Twenty-year record. Currently attached to Naval Special Warfare Training Command out of Coronado.”

Silence hits the hallway like a physical thing.

Even the fluorescent lights seem to buzz more quietly for a heartbeat.

Marine dad number two’s mouth opens, then closes. His wife stares, all her earlier confidence evaporated. The teenage boy’s hands drop to his sides like he suddenly realizes they’re just hands, not weapons or shields. The teenage girl looks between Rowan and Mia, her eyes wide in a way that has nothing to do with makeup.

Rowan doesn’t smirk. She doesn’t add “Believe me now?” the way the moment invites. She just turns away from the wall of faces and returns to the only thing that matters.

Her daughter.

“Hey,” she says again, crouching beside Mia. “Can you stand?”

Mia nods, her eyes huge. “Yeah,” she whispers. “I’m okay.”

Rowan offers her a hand, not because she thinks Mia can’t stand on her own, but because sometimes the point of an offered hand isn’t physical support. Mia takes it. She rises slowly, steadying herself with the other hand against the bench. The pain in her shin flares when she puts weight on her leg, but she sets her jaw. She’s her mother’s kid, and there are too many eyes on her for her to falter.

The door at the far end of the corridor swings open again, this time with more urgency. Ms. Caffrey steps out, clipboard in hand, her expression already stripped of the carefully arranged PTA-night smile.

She heard the impact.

She heard the gasps.

And now she sees the layout of the hallway: Rowan standing, calm and controlled; a Marine dad straightening with a wince; Mia with a flushed face and a leg she’s putting weight on too carefully; other parents hovering with guilt clinging to them like a second skin.

“Mia?” Ms. Caffrey asks, hurrying forward. “What’s going on?”

Rowan rises slowly to her full height, placing herself subtly between the Marines and her daughter. She doesn’t run ahead of anyone’s story. She doesn’t overdramatize. She just tells the truth.

“My daughter was cornered,” she says, voice clear. “Bullied. Struck. Filmed. Mocked for telling the truth about who I am.”

The words hit the teacher like a wave.

Her face drains of color. Her eyes dart to the teenage boy with the phone clutched in his hand.

“Is that true?” she asks.

The boy’s mouth opens, but nothing comes out.

For a moment, nobody speaks.

Then, from farther down the hall, a small voice cuts through the fog.

“I saw it,” says a thin boy in oversized glasses, the one who passed earlier pretending not to notice. He raises his hand halfway, out of habit. “They kicked her,” he says. “He kicked her. She didn’t bump into him. He kicked her.”

Rowan doesn’t turn toward him, but she notes his presence, logs his courage.

Ms. Caffrey’s voice tightens into the tone teachers use when they’re walking the edge between anger and procedure. “All of you,” she says to the Marines and their families, “into the staff room. Now.”

Marine dad number one starts, “It was a misunderstanding—”

“I don’t want spin,” Ms. Caffrey cuts in, the clipboard trembling slightly in her hand. “I want statements. Separate chairs. This is a serious incident.”

Rowan looks at Mia. Their eyes meet. Rowan gives her a small nod, the kind that says You did nothing wrong. The kind that says I am here, I am staying, this is not going to be swept under anyone’s rug.

A school counselor appears a moment later, summoned by a student aide who heard the noise and knew enough to fetch backup. She’s wearing a cardigan with an ID badge and holds a legal pad against her chest.

“Can I sit with you a minute?” she asks Mia, gentle.

Mia nods, eyes still locked on her mother even as she moves to the bench just outside the staff room door. The counselor sits beside her, leaving enough space that Mia can decide if she wants to close it.

“I’m so sorry this happened,” Ms. Caffrey says quietly to Rowan. “We’ll start a formal report immediately. We have protocols for this.”

“Good,” Rowan replies. “Because if it happens again…”

She doesn’t finish the sentence, but she doesn’t need to. The unfinished thought hangs heavier than any completed threat would.

The teenage boy glances down at his phone, screen still on the camera app. His thumb hesitates above the buttons.

“Let me see it,” Rowan says.

He hesitates. Then, under the combined force of her gaze and his own shame, he holds the phone out.

Rowan doesn’t scroll. She doesn’t linger on the paused frame that shows her daughter curled around a folder on a school floor. She taps two icons: trash. Confirm. The video disappears. She hands the phone back.

“This is evidence,” Ms. Caffrey begins, protest instinctively forming.

“It’s humiliation,” Rowan says quietly. “You have witnesses. You have a hallway full of people who can testify. You don’t need a video of my daughter on the ground living on some cloud server in another state.”

The counselor nods slowly. “We can proceed without it,” she says. “He can describe what he recorded, if needed.”

Rowan’s shoulders relax a fraction, but only a fraction.

The staff room feels too small for what comes next.

The Marines and their wives sit in plastic chairs, suddenly looking more like kids waiting outside a principal’s office than grown adults with years of service and base hashtags on their social media. The teenage boy sits closest to the door, his phone face down on his thigh. The teenage girl keeps her arms crossed, eyeliner smudged at the edges from where she rubbed her eyes without thinking.

Rowan doesn’t sit. She stands just inside the doorway, arms folded loosely, her presence filling the space more than any raised voice could. She positions herself in a way that allows her to see both the adults and her daughter, who’s still in the hallway with the counselor.

It’s Marine dad number one who cracks first.

“We’re sorry,” he mutters, staring at the tabletop between them. “Shouldn’t have called her a liar.”

Rowan doesn’t rush to accept the apology. She doesn’t rush to reject it either. She turns slightly, looking at Mia, whose legs are crossed now, folder resting neatly beside her on the bench, counselor murmuring something that makes her nod.

“Do you want to hear them say it to you?” Rowan asks her, voice carrying easily into the staff room.

Mia hesitates. Then she nods once.

Rowan turns back.

“Say it again,” she tells the Marines. “To her.”

Marine dad number one exhales like the words cost him money. “Mia,” he says, his voice stiff, “we’re sorry. We shouldn’t have said the things we said.”

Marine wife with the hoop earrings jumps in, trying to soften the edges. “You just surprised us,” she says. “You have to understand—what you said, it sounded… big. You should have said it differently.”

Rowan’s expression doesn’t change, but her tone cools.

“You don’t get to rewrite this,” she says. “You mocked a twelve-year-old girl. You told her the truth was a joke. Then you let your son lay a foot into her leg because you decided she had nobody here to stop you. That’s what happened.”

The teenage boy looks up, red blotches forming on his face. “I didn’t mean to hurt her,” he says, voice cracking.

“You did hurt her,” Rowan answers. “You just didn’t expect consequences. There’s a difference.”

Marine dad number two shifts in his seat. “We didn’t know she was yours,” he repeats, like it’s a detail that matters.

Rowan’s eyes flash once. “You shouldn’t need to know whose child she is,” she says. “This is a California public school. Every kid in this building is supposed to be treated with a baseline of decency. They shouldn’t have to pull out a parent’s résumé to earn protection from adults.”

No one argues.

Ms. Caffrey stands in the corner of the room, clutching her clipboard so hard the cardboard bends. She doesn’t intervene. She doesn’t smooth anything. She lets the truth stand naked in the space between them.

Rowan looks back at Mia, then crouches again in the doorway to speak to her at eye level.

“You spoke the truth,” she says gently. “They couldn’t handle it. That’s not your fault.”

Mia’s eyes fill again, but the tears stop at the brink. She leans forward just enough to tuck her head against her mother’s shoulder for three solid seconds. Rowan wraps an arm around her, holding exactly as tightly as needed, no more, no less. Then she stands.

The official process begins. Forms are pulled from drawers. Words like “incident report” and “harassment” and “physical contact” get scribbled on lines under fluorescent light. The counselor notes the bruise on Mia’s shin. Someone mentions the words “military liaison,” because in a town this close to the ocean and the base, every serious school issue eventually brushes up against the shadow of the uniform.

The PTA meeting is officially postponed. Ms. Caffrey pushes her glasses up her nose and announces to the remaining parents that they’ll reschedule for another week, that some “unforeseen circumstances” have come up. She doesn’t offer details. She doesn’t have to. Hallway whispers outrun official announcements in any American school.

Chairs are stacked. Paper cups with rings of coffee at the bottom are tossed into trash bags that crinkle loudly in the emptying room. Parents leave in pairs and clusters, their faces mixing curiosity, concern, and the kind of guilty relief that it wasn’t their kid in the hallway.

Rowan walks beside Mia down the hall, one hand resting lightly on her daughter’s shoulder. She doesn’t steer her. She doesn’t guide her like a fragile object. She walks with her, pace matched, stride even.

As they pass the open staff room door, mumbled apologies float out behind them like weak smoke.

“Tell her we’re sorry again.”

“We didn’t think—”

“We just… misunderstood…”

Rowan doesn’t pause.

Mia doesn’t, either.

Outside, the air has cooled. Dusk settles over the school’s flagpole, the American flag pulling slightly in the ocean-tinged breeze. The parking lot lights flicker on with a low hum, bathing the cars in a pale glow. A police cruiser passes on the street beyond the chain-link fence, lights off, just part of routine patrol.

A few leaves scrape across the asphalt, driven by the same wind that ruffles the top of Mia’s braid.

At the curb, Rowan unlocks the car with a quiet chirp and opens the passenger door.

“Did I do something wrong?” Mia asks as she climbs in, the question small and fragile but necessary.

Rowan takes a moment before she answers. She closes the door gently. Walks around the front of the car. Slides into the driver’s seat. Starts the engine. The dashboard glows soft blue. The radio comes on low, some country song about trucks and heartbreak, and she reaches out to turn the volume down to a faint murmur.

Then she looks over at her daughter.

“No,” she says. “You told the truth. They weren’t ready to hear it. That’s on them, not you.”

Mia looks down at her folder, now resting on her lap again, its edges straightened. “Are you mad at them?” she asks.

Rowan exhales once, a slow breath that lets some tension out but doesn’t fully release it. “Not really,” she says. “Not anymore.”

“Why not?” Mia presses, frowning slightly.

“Because they already learned what they needed to,” Rowan answers. “The hard way.”

Mia’s mouth curves into the smallest of smiles, the kind that shows up when the world has been confusing and then, suddenly, a little piece of it makes sense again.

“You didn’t yell at them,” she says.

“I didn’t have to,” Rowan replies. “Next time someone calls you a liar, you let me handle the adults. That’s my lane.”

Mia nods, more sure now. The bruise on her leg still throbs, but the ache has shifted. It feels less like something done to her and more like evidence of something survived.

They back out of the lot slowly. At the edge of the driveway, Rowan pauses, foot on the brake, and glances toward the school entrance. Marine dad number one stands there, arms folded, watching the car. The earlier swagger is gone. He doesn’t sneer. He doesn’t smirk. He just dips his head once, a small, wordless acknowledgment that the story he told himself about who was in charge of that hallway wasn’t true.

Rowan doesn’t nod back.

She just turns the wheel, pulls onto the road, and leaves the school behind in the rearview mirror, its windows glowing like small rectangles of memory under the darkening American sky.

The night in San Diego moves on. Somewhere out on the Pacific, navy ships cut through black water, their lights dim, crews awake in shifts. At Naval Base Coronado, training instructors review schedules and gear lists for the next day’s evolutions—ocean swims, timed runs, obstacle courses that test the boundaries of human endurance. The kind of training that people like the Marines in the hallway joke about over beers, and people like Rowan live and bleed through in real life.

In a small second-floor apartment not far from base housing, a wall calendar still shows a circle around the date of the progress night. On the kitchen counter, a plate with one uneaten cookie from the staff refreshment table sits under a square of plastic wrap. On the fridge, a magnet in the shape of the state of California holds up a crayon drawing of a woman in a wetsuit standing in front of a giant wave, her hand resting on a smaller figure’s shoulder.

Later, in that apartment, Mia will peel off her jeans and examine the bruise on her leg in the bathroom light. It will be darker now, purple-blue with a faint pattern from the rubber sole. She will touch it lightly with her fingertips and wince, then straighten, looking at her reflection. She will see her own dark braid, her own shoulders, her own eyes. She will see the way her chin juts out when she’s decided something.

She will think, They saw her. They all saw her. She was real, and now they know.

Rowan, in the kitchen, will rinse out a pair of plastic cups and stack them upside down on the drying rack. Her phone will buzz with a message from a teammate on base: a link to a local community Facebook group already humming with secondhand versions of what happened at Redwood Community School. Some people will call her a hero. Some will call her overdramatic. Some will say “kids these days are too soft.” Some will point out that bullying is older than the school system itself and just as stubborn.

She will not comment.

She spends her life avoiding unnecessary spotlights. Her work, by nature, is often in the shadows—training others, shaping discipline, teaching recruits how to move precisely through dangerous spaces. Tonight was a different kind of mission: a hallway instead of a training range, a plastic chair instead of a combat zone, but the stakes mattered just as much.

In her bedroom, she’ll lay out her gear for the next morning’s run. Boots. Socks. Compression shirt. She’ll move through the motions with the ritual calm of somebody who has packed kits for deserts and mountains and ships and foreign airfields. As she zips up her duffel, she’ll picture her daughter’s face on the hallway floor under a peeling poster, and she will tuck that image into the same mental compartment where she keeps memories of long nights in cold surf, teammates on either side of her and instructors yelling on the shoreline.

Silence, she knows, is a tool.

Used wrong, it’s permission for cruelty.

Used right, it’s precision.

Tonight, in that American school hallway, she didn’t shout. She didn’t blare her rank like a siren. She didn’t drag anybody by the collar. She simply walked in, saw what needed correcting, and corrected it. Her record of service includes deployments and classified operations. The staff report at Redwood Community School will include phrases like “parent intervened” and “physical redirection” and “verbal accountability.” The Marines will sign incident forms and maybe sit through uncomfortable conversations with their base superiors about representing the Corps off duty.

Mia will go to school the next day with a bruise on her leg and a story at her back that nobody will laugh at to her face again. There will be whispers, yes. There will be kids sidling up to her locker to ask, “Was that really your mom?” There will be teachers watching her with new awareness, making sure that this time, when a child says something unbelievable, they think twice before joining in the giggles.

At night, in bedrooms and living rooms across town, parents will say things like, “Did you hear about that Navy SEAL mom at Redwood?” and “Can you imagine?” and “Good for her,” over dinners, over drinks, over late-night scrolling. In a country that loves heroes in abstract and sometimes forgets what they look like in grocery stores and school hallways, this story will travel.

It will travel because there’s something about a quiet correction that cuts through noise.

The next time Mia hears someone laugh at a truth that sounds too big, she’ll remember how the hallway felt when her mother stepped inside. She’ll remember that being doubted doesn’t make a truth smaller. It just makes the reveal sharper when the door finally opens and the person they said didn’t exist walks through, perfectly real, perfectly calm, and absolutely unwilling to let a lie stand over her child.

And somewhere, past the base gates and the school fences and the suburban streets lined with mailbox flags and basketball hoops, in a country that runs on stories as much as electricity, someone will be scrolling, thumb hovering above a screen, reading about a Navy SEAL mom who walked into a middle school hallway in Southern California and reminded a room full of Marines, parents, and kids what discipline actually looks like.

Not in shouting.

Not in spectacle.

But in precision.

News

On the way to the settlement meeting, i helped an old man in a wheelchair. when he learned that i was also going to the law firm, he asked to go with me. when we arrived, my sister mocked him. but her face turned pale with fear. it turned out the old man was…

The invoice hit the marble like a slap. “You have twenty-four hours to pay forty-eight thousand dollars,” my sister said,…

After my parents’ funeral, my sister took the house and handed me a $500 card my parents had left behind, like some kind of “charity,” then kicked me out because I was adopted. I felt humiliated, so I threw it away and didn’t touch it for five years. When I went to the bank to cancel it, the employee said one sentence that left me shocked…

A plain white bank card shouldn’t be able to stop your heart. But the moment the teller’s face drained of…

My sister locked me inside a closet on the day of my most important interview. I banged on the door, begging, “This isn’t funny—open it.” She laughed from outside. “Who cares about an interview? Relax. I’ll let you out in an hour.” Then my mom chimed in, “If not this one, then another. You’d fail anyway—why waste time?” I went silent, because I knew there would be no interview. That “joke” cost them far more than they ever imagined.

The first thing I remember is the smell. Not the clean scent of morning coffee or fresh laundry drifting through…

On Christmas Eve, my seven-year-old found a note from my parents: “We’re off to Hawaii. Please move out by the time we’re back.” Her hands were shaking. I didn’t shout. I took my phone and made a small change. They saw what I did—and went pale…

Christmas Eve has a sound when it’s about to ruin your life. It isn’t loud. It isn’t dramatic. It’s the…

On my 35th birthday, I saw on Facebook that my family had surprised my sister with a trip to Rome. My dad commented, “She’s the only one who makes us proud.” My mom added a heart. I smiled and opened my bank app… and clicked “Withdraw.

The candle I lit on that sad little grocery-store cupcake didn’t glow like celebration—it glowed like evidence. One thin flame,…

My son-in-law and his father threw my pregnant daughter off their yacht at midnight. She hit something in the water and was drowning in the Atlantic. I screamed for help, but they laughed and left. When the Coast Guard pulled her out three hours later, I called my brother and said, “It’s time to make sure they’re held accountable.”

The Atlantic was black that night—black like poured ink, like a door slammed shut on the world. Not the movie…

End of content

No more pages to load