The five crisp $100 bills looked obscene against the worn wood of the counter.

They lay there like they belonged in a private bank in downtown Seattle, not on the scratched surface of Brew Haven, the little coffee shop tucked between a thrift store and a laundromat on Capitol Hill. Afternoon light from Pine Street spilled through the big front windows, catching the edge of each bill so they glowed faint gold.

I slid them back toward him with two fingers, as if they might burn.

“I am not for sale,” I said. “This is too much for a tip. That’s the third time this week, and I’m not taking it.”

The room shifted. Jasmine nearly dropped the milk frother. The elderly couple at table four paused mid-conversation. Even the indie playlist humming from the speaker seemed to dim.

Across from me, in a suit that probably cost more than three months of my rent, Kang Si-wan just blinked.

He looked like he belonged in some glass tower by Pike Place Market, not here with our chipped mugs and mismatched chairs. Dark hair, perfectly styled. Clean jawline. Watch that whispered high-end, even if I couldn’t name the brand. At twenty-eight, he was the CEO of Kang Industries, a fact Jasmine had Googled in a panic the very first time he walked in.

And right now he was staring at me like I’d started speaking another language.

“It’s just a tip,” he said. His voice carried that slight, soft Korean accent that turned his consonants into something almost musical. “For excellent service.”

“Excellent service is a latte made at the right temperature.” I tapped the top bill with my nail. “That’s a down payment on a car. I don’t need your guilt money, or your charity, or whatever this is.”

A flush crept up his neck, quick as the afternoon shadows sliding across Pike Street outside. He looked hurt—really hurt—for half a heartbeat before his expression reset. There it was: the practiced, polite smile wealthy men in downtown Seattle wore like armor. The one that said, It’s fine, nothing touches me. The one that lied.

“It’s not charity, Brianna.”

“Then what is it?” I pushed the money a little closer to his side of the counter. The bills skated over the wood. “Because men like you don’t leave five hundred–dollar tips on four–dollar coffee unless you want something.”

He opened his mouth, closed it again. For once, he had nothing to say. He picked up the money, squared the edges with almost obsessive precision, slid it back into his wallet, and turned toward the door.

The bell chimed as he stepped out onto the Seattle sidewalk, swallowed by the drizzle and the bright bus ads rolling past on Pine.

The shop breathed again.

“Girl, have you lost your mind?” Jasmine hissed, rushing over as the door swung shut. Her gold hoop earrings trembled. “Do you know who that is?”

“Yeah.” I grabbed a rag and wiped the same imaginary spot on the counter. “Another rich man who thinks everything has a price tag.”

What I didn’t say—what I couldn’t say in front of Jasmine or the old couple or the college kids hunched over laptops—was that I’d seen the way he looked at me. Not like a server. Not like an afterthought.

Like I was something rare. Like I was something he wanted and didn’t quite understand yet.

And that terrified me more than anything.

Because I’d seen this movie before, right here in America, in a little apartment in South Seattle where the Space Needle looked tiny in the distance. I’d watched my mother sit by the phone every holiday, every birthday, in a nice dress she couldn’t afford, waiting for a call from a man who lived in another part of town with his “real” family.

He’d never show up, but sometimes he sent boxes: fancy dolls, tiny velvet dresses, a pair of shoes my mother made me wear only on Sundays. Gifts that smelled like apologies and hotels and promises he didn’t keep. Guilt wrapped in tissue paper.

I’d watched my mother take those boxes like they were proof she mattered to him. Like the money made up for the empty chair at every table.

I wasn’t going to be her.

Not for any man.

Not even for the man whose sad eyes made my heart do stupid things I could not afford.

Six months earlier, the first time Kang Si-wan walked into Brew Haven, I was arguing with the espresso machine like it was a person who kept letting me down.

“Come on,” I muttered, smacking the side panel near the steam wand. “Don’t do this to me today. Please, not the morning rush.”

“Problems?”

I looked up and forgot what I was going to say.

He stood framed in the doorway, backlit by September sunlight that bounced off the windshield of a parked car on Pine Street. Dark hair pushed back from his face, sharp cheekbones, clean white shirt under a charcoal blazer that did not come from any mall I’d ever been inside. He looked like he’d gotten lost on his way to a meeting in a downtown high-rise.

“Nothing I can’t handle.” I twisted the knob. The espresso machine coughed, then finally obeyed. “What can I get you?”

He studied the chalkboard menu above my head like it held the answer to life. People behind him fidgeted with their phones and tote bags and headphones, impatient in the way only Seattle coffee people could be.

“What do you recommend?” he asked.

“Depends.” I wiped a stray coffee splatter off the counter. “Are you a play-it-safe kind of person or a take-risks-and-hope-you-don’t-regret-it kind of person?”

A slow smile tugged at the corner of his mouth. “I’d like to think I take risks.”

“Then the honey lavender latte. It sounds weird, but it works.”

“I’ll trust you.”

As I ground the beans, measured shots, and poured milk, I could feel him watching me. Not in the gross way guys sometimes watched—you learn to spot that one fast—but with focused curiosity, like he was trying to solve a puzzle.

“I’m Si-wan,” he said when I slid the drink across the counter.

“Brianna,” I replied. “Enjoy your weird coffee.”

He laughed, and something in my chest did a tiny, traitorous flip.

No, I told myself. Absolutely not. We are not doing this.

He took a cautious sip. His eyes widened.

“This is… really good.”

“I told you. Risk-takers get rewarded around here.”

He pulled out his wallet. A flash of black card. The kind you only saw in movies or in the hands of people who had opinions about yacht sizes. He handed me a fifty for a six–dollar drink.

“Keep the change,” he said.

“The change is forty-four dollars.”

“I know.”

I counted out forty-four dollars from the till, folded them neatly, and placed the cash back in his hand.

“I don’t take tips bigger than the order,” I said. “House policy. My house.”

He looked genuinely confused, like no one had ever refused his money before. Which, now that I thought about it, might actually be the case.

Then that flicker of confusion became something else. Interest. Intrigue.

“Okay,” he said finally. “Have a good day, Brianna.”

He left with his latte and his forty-four dollars. Jasmine materialized beside me like she’d teleported.

“Did you just turn down a forty-four–dollar tip?” she hissed.

“Yep.”

“Why?”

“Because nothing’s free, Jazz.” I grabbed the next order. “Especially not from men who carry black cards and wear watches that cost more than my car.”

He came back the next day.

And the day after that.

Always ordering the honey lavender latte. Always trying to leave tips far beyond the cost of his drink. Always watching me like I was the most interesting part of his day.

On day seven, three dozen long-stem red roses arrived at the shop in a huge glass vase, delivered by a teenager in a Rainier Beach High hoodie. The roses were perfect, lush and dramatic, like something from a movie proposal scene in a downtown rooftop restaurant.

The card said, in neat handwriting:

For the girl who won’t take my money.

Maybe you’ll take these instead.

– S.

Jasmine squealed. The morning customers cooed. Phones came out. People took pictures.

I stared at the flowers like they were a bomb.

“What are you going to do?” Jasmine whispered.

I walked around the counter, picked up the vase—it was heavy—and set it on a table. Then I began pulling out roses one by one.

“Excuse me,” I said to the elderly woman who came in every morning for decaf and a blueberry muffin, the one who always told me about her grandkids in Tacoma. “Would you like a rose?”

Her eyes lit up. “Oh, honey. They’re beautiful.”

I gave two to the exhausted young mom trying to wrangle twin toddlers in a stroller. Three to a college student with dark circles under his eyes and a stack of textbooks about calculus and environmental policy. One to the postal worker who came in on his break.

Joy bloomed across the room in little red bursts.

“Brianna, what are you doing?” Jasmine hissed.

“Spreading joy.” I tucked the last rose behind a high school girl’s ear. “Isn’t that what flowers are for?”

By the time Si-wan walked in twenty minutes later, carrying his usual quiet confidence, there wasn’t a single rose left in the vase.

He looked from the empty glass to me, to the scattered roses throughout the shop. You could see the exact moment he understood.

“You gave them away,” he said.

“They were too pretty to keep to myself.” I started his latte without asking. “Besides, I’m allergic.”

“You’re allergic?” His brows knit.

“No,” I admitted. “But you didn’t know that.”

He exhaled a tiny laugh and leaned against the counter. His cologne was subtle and clean; it smelled like cedar and something expensive.

“Why won’t you let me do something nice for you?” he asked.

I stopped mid-pour and looked up at him. Really looked. He seemed genuinely confused, not offended.

“You want to know why?” I set the milk pitcher down and wiped my hands on my apron.

“When I was seven,” I began, “my mom used to dress me up every Christmas Eve. South Seattle apartment. Cheap tree with ornaments from Goodwill. She’d put my hair in curls, smooth my dress, and we’d sit by the window looking at the I-5 traffic and the Space Needle in the distance.”

His expression softened, focus sharpening.

“She’d tell me my father was coming. That this year would be different. That he promised.”

My throat tightened, but the words kept coming, pulled out by something in his eyes.

“He never came. Not once. But you know what arrived every so often?” I gave a short, humorless laugh. “Boxes. Dolls too fancy to play with. Tiny velvet dresses I had nowhere to wear. Money folded in cards with three-word messages. It felt like guilt wrapped in tissue paper. Like hush money.”

I slid his drink across the counter.

“So forgive me if I don’t trust nice gestures from men who have everything,” I finished. “Forgive me if I don’t want to be the girl who gets presents instead of presence.”

I turned away before I could see his reaction, walked to the back room, and leaned my forehead against the cool metal of the fridge. My hands trembled. I hadn’t talked about my father to anyone but my mom and Jasmine. Definitely not to a customer.

By the time I came back out, his latte sat untouched on the counter. He was gone.

Under the cup, a napkin lay flat. On it, in neat handwriting, were six words:

I’m sorry that happened to you.

But I’m not him.

Two weeks later, he came in with a folder.

The morning rush had just ended. The usual Pike Street parade was visible through the big front windows: dog walkers, tech bros with lanyards, college kids with headphones, tourists trying to find Pike Place Market with Google Maps. I was wiping down a sticky table when his shadow fell across it.

“I have a proposition for you,” he said.

“Not interested,” I replied without looking up.

“You haven’t heard it yet.”

“Don’t need to.” I straightened, tossed the dirty rag back into the bucket, and met his eyes. “The answer’s no.”

He smiled, the corner of his mouth twitching like I’d said something genuinely entertaining.

“Brianna,” he said, “just listen.”

“I don’t like that sentence,” I muttered. “It’s usually followed by something terrible.”

“I know you’re taking online art classes through Seattle Community College,” he began. “I know your car is one breakdown away from retirement. I know you work doubles most weeks.”

Cold ran down my spine.

“You’ve been checking up on me?”

“I pay attention,” he replied. “There’s a difference.”

He opened the folder and slid it across the table. Smooth paper, thick stock, the kind Jasmine’s corporate clients sometimes used for presentations about rebrands and Q4 projections.

“I want to pay for your education,” he said. “Full tuition. Whatever art school you want to attend. And I’ll buy you a reliable car. Nothing flashy. Just something safe.”

The shop went quiet. Even the milk steamer seemed to hold its breath.

“In exchange for what?” I asked. My voice came out sharper than I intended.

“Nothing.” He held my gaze. “No strings. I just want to help.”

“Help,” I echoed.

The word tasted like old Christmas cards.

I laughed, and it came out brittle. “You want to help? Here’s how you can help: you can stop treating me like a project. Stop acting like I’m some charity case you can fix with your father’s money. Stop assuming every problem can be solved by throwing cash at it.”

Color rose in his face. “That’s not what I’m doing.”

“Then what are you doing, Si-wan?” I demanded. “Why are you here every single day? Why the tips, the flowers, the background checks, the grand offers?”

My voice had gotten loud, but I couldn’t reel it back in. “What do you want from me?”

He looked like I’d pinned him to the wall with those words. The air between us grew heavy. Customers shifted in their seats, pretending not to listen and failing miserably.

“I want to know you,” he said quietly. “I want to take you to dinner. I want to hear about your art and your dreams and what makes you laugh. I want a chance.”

“No,” I said.

The word landed like a stone.

“I am not for sale,” I added, softer but sharper. “Not for tuition, not for a car, not for anything. I don’t care how lonely you are or how much money you have. Find someone else to fix. Someone else to save. Someone else to make you feel like a good guy.”

I picked up the folder and pressed it back into his hands.

“We’re done here,” I said, and headed for the back room, heart pounding so hard I could feel it in my teeth.

I heard Jasmine apologizing to him, heard the door chime as he left, heard the customers explode into hushed, excited whispers. In the staff room, between the mop and the bags of beans, I let myself cry for exactly sixty seconds.

Because saying no to him felt like closing a door I hadn’t realized I wanted to walk through.

But I’d watched my mother stand by that door for twenty years, waiting for a man who chose someone else. I’d watched her build a life around an empty space at the table.

I refused to repeat her story.

That evening, across the city in a penthouse overlooking Elliott Bay and the Seattle skyline, Kang Si-wan sat on a leather sofa and stared at the lights.

From his floor-to-ceiling windows, he could see the Great Wheel glowing down by the waterfront, the cranes at the port, the faint outline of the mountains beyond. It was the view people in Seattle dreamed about when they bought lottery tickets.

He barely saw it.

“So let me get this straight,” his best friend, Tae-min, said without looking up from the game on his phone. “You offered to pay for her school, buy her a car, and she told you to go away.”

“Essentially, yes,” Si-wan replied.

Tae-min burst into laughter so loud it echoed off the glass. “Oh man. I like her already.”

“It’s not funny,” Si-wan said, but his lips quirked.

“It’s hilarious,” Tae-min insisted. “Do you know how many people in this city would sell their souls for what you just put on the table? Do you know how many women have literally thrown themselves at you because you’re ‘Seattle’s youngest CEO’?”

He mimed quotation marks in the air.

“And this one girl in a coffee shop looks at you and says, ‘No thank you, absolutely not.’”

Si-wan rubbed his face. “Every woman I’ve met has wanted something,” he said. “My name, my money, my connections. She wants nothing from me. I don’t understand it.”

“Maybe that’s exactly why you’re obsessed.”

“I’m not obsessed,” he protested.

“Dude.” Tae-min paused his game. “You’ve been going to the same coffee shop every day for three weeks. You memorized her schedule. You hired someone to look into her background.”

“I tore up that report without reading it,” Si-wan said.

“After you paid for it,” Tae-min pointed out.

He set his phone down and turned toward his friend. “Listen, I’m going to tell you something you’re not going to like. This girl, Brianna? She’s not playing. She’s not trying to be mysterious or make you chase her. She genuinely does not want what you’re offering. And that terrifies you.”

“It does not terrify me,” Si-wan said.

“It does,” Tae-min replied. “Because you’ve never had to earn someone’s affection. You’ve just had to be you—with the company, the name, the condo over Pike Place—and that’s been enough for most people. For once, it’s not.”

Silence sat between them, heavy as the late-night fog rolling in off Puget Sound.

“So what do I do?” Si-wan asked finally.

“You stop trying to buy her,” Tae-min said. “And you start trying to know her. Real talk. Real effort. Real vulnerability. No black cards. No grand gestures. Just you.”

“That sounds harder than a board meeting with hostile investors,” Si-wan muttered.

“Welcome to actual human connection.”

Three days later, he was driving home along Rainier Avenue after a late meeting when he saw her.

Brianna’s car—a faded blue sedan that had lived three lives too many—sat at an awkward angle on the side of a side street, hood up. Rain drummed against the asphalt, the sky that particular Seattle gray that felt more like a mood than weather. Brianna stood beside the open hood with her phone pressed to her ear, curls plastered to her cheeks.

He pulled over before he could think better of it.

“Need help?” he called over the rain as he stepped out, his designer shoes instantly regretting their life choices.

She looked up. Water traced down her face, catching on her lashes. For a second her jaw tightened, that familiar wall dropping back into place.

“I’m fine,” she shouted back. “Tow truck’s coming.”

“In this weather?” He glanced at the dark street. “That could take hours.”

“Then I’ll wait hours,” she said.

He should have driven away. He really, truly should have. She’d been crystal clear. But the rain was coming down harder now, turning the asphalt into a mirror of streetlights and brake lights.

“At least wait in my car where it’s dry,” he said. “I’ll drop you wherever you need to go.”

“No.”

“Brianna, you’re going to get sick.”

“I’d rather get pneumonia than owe you anything,” she snapped.

The words hit him harder than the cold. He nodded, swallowed, and backed away.

He got into his car—a black sedan far more expensive than it appeared—and parked twenty feet behind her. He turned off the engine, leaving only the soft hum of the heater.

“What are you doing?” she called, exasperation cutting through the rain.

“Waiting,” he shouted back.

“For what?”

“For your tow truck. Making sure you’re safe.”

“I don’t need you to do that.”

“I know,” he said. “I’m doing it anyway.”

They stayed like that for two hours.

She stood by her car, soaked and stubborn, phone clutched in one hand. He sat in his, watching the rhythm of the wipers and the shape of her in his side mirror. Twice he opened his door to insist she get in. Twice he shut it again, remembering her words: I’m not for sale. I’m not a project.

By the time the tow truck arrived, the rain had drilled into his bones. The driver loaded her car with bored efficiency.

Brianna walked over to his window and motioned for him to roll it down.

“You’re an idiot,” she said.

“Probably,” he agreed.

“You didn’t have to wait.”

“I know,” he said.

Something shifted in her eyes, just a fraction. A tiny crack in the wall.

“Why do you keep doing this?” she asked. “Why do you keep showing up?”

He thought of the script he could say. Something charming and rehearsed. But Tae-min’s words echoed in his head: real vulnerability.

“Because when I’m with you,” he said slowly, “I feel like a person. Not a bank account. Not a last name. Not a headline. Just… me. And I haven’t felt that way in a really long time.”

Rain slid off her curls in slow streams. She studied his face like she was trying to decide if he was lying.

“Goodnight, Si-wan,” she said finally.

“Goodnight, Brianna,” he replied.

He watched her climb into the cab of the tow truck, watched the truck pull away, watched the taillights disappear into the rain. Then he sat there for ten more minutes in his soaking suit, wondering why doing the right thing felt so much like losing.

The next morning, in the cramped storage room at Brew Haven, Jasmine cornered Brianna.

“We need to talk,” she announced, folding her arms.

“If this is about Si-wan—”

“It is one hundred percent about Si-wan,” Jasmine said. “That man sat in the rain for two hours last night just to make sure you got home safe. Do you understand how rare that is in this city? Most guys won’t even wait until your Uber actually arrives.”

“He probably wanted to feel like a hero,” Brianna muttered, stacking cups.

“Or maybe he actually cares,” Jasmine shot back. “Look, I get it. I know what your mom went through. I know why you’re scared. But you’re punishing him for what another man did.”

“I’m protecting myself.”

“No,” Jasmine said gently. “You’re hiding. There’s a difference.”

Brianna felt her throat close.

“He shows up every day,” Jasmine continued. “He doesn’t push when you say no. He waited in the rain. When does that count? When does someone earn credit for proving they’re different?”

“What if I let him in and he leaves?” Brianna whispered. “What if I’m just a phase? An interesting challenge. Once he figures me out, he moves on to the next thing.”

“What if he doesn’t?” Jasmine countered. “What if you’re so busy protecting yourself from possible pain that you miss something real?”

“I don’t know how to do this,” Brianna said. “I don’t know how to trust someone like him. His life…” She gestured toward an imaginary skyline. “My mother waited her whole life for a man who never chose her. I can’t… I won’t…”

“Then start small,” Jasmine said. “Have one conversation that isn’t about coffee or your boundaries. Let him see you. Not the walls. You.”

A week passed with no sign of him.

Brianna told herself she was relieved. She focused on midterms, on customers, on rent. But every time the bell chimed, her eyes flicked to the door.

On the eighth day, just when she’d convinced herself he’d finally listened and moved on, he walked in.

No suit. No tie. Just jeans, a plain white T-shirt, and a flannel that made him look almost painfully normal. His hair was less styled, like he’d run a hand through it on his way out the door. He stood in line like everyone else.

“You look different,” she blurted when he reached the counter.

He glanced down at his clothes. “No suit,” he said. “No driver. I took the bus. Just a guy getting coffee.”

He smiled, and it looked almost… nervous.

“I’d still like the honey lavender latte,” he added. “If you’re offering.”

She made his drink, hyper-aware of his eyes on her. When their fingers brushed as she passed him the cup, that flutter hit again, softer now but still there.

“Can I ask you something?” he said. “And you can tell me to mind my business if you want.”

“Okay,” she said slowly.

“What kind of art do you do?”

She blinked. That was not the question she’d expected.

“Mostly paintings,” she said. “Abstracts. Some portraits.”

“What inspires you?”

Just like that, a door cracked open.

They talked while she wiped the counter and pulled shots and refilled the syrup bottles. About color and light and why she loved messy brushstrokes. About how she saw the world differently when she built it with paint instead of coffee.

He listened. Really listened. Asked questions that showed he remembered details she’d tossed out weeks ago. The way she’d painted the view of South Seattle from her rooftop. The series she wanted to do on people waiting—at bus stops, in hospital lobbies, at windows.

“I’d like to see your work sometime,” he said eventually. “If you’d want to show me.”

“Maybe,” she said, the word out before her fear could stop it. “Maybe sometime.”

His whole face lit up like she’d offered him front-row tickets to something important.

“Yeah?” he asked.

“Don’t make it weird,” she said, and he laughed.

Over the next two weeks, it became their routine.

He came in once a day, sometimes twice. Some days he stayed through the mid-morning lull, laptop open, tapping away at emails. Other days he just grabbed coffee, chatted for five minutes, and left with a smile.

He told her about growing up in a house on Mercer Island so big he used to get lost in it, about parents who attended charity events in downtown hotels but missed school plays. About being groomed for Kang Industries since middle school: internships in their own company, private tutors, “networking events” at twelve.

She told him about nights sleeping in a hospital chair in Harborview while her mom worked overtime as a nurse. About drawing on napkins when there was nothing else to do. About watching planes land over Lake Washington and imagining she could paint the trails they left.

He told her truly terrible jokes that made her groan and then laugh anyway. She rolled her eyes and called him out when he was being dramatic.

Something fragile and real grew in the spaces between orders and closing shifts.

One afternoon, he said, “There’s a community art show next Friday, down in Pioneer Square. Local artists. Free admission. I thought maybe… if you’re free… we could go. Just to look.”

Her heart did that stupid flutter again. It was perfect: no rooftop bar, no five-star restaurant, just art and people who cared about it.

“It doesn’t have to be a date,” he added quickly. “If you don’t want it to be. Just two people who like art looking at art.”

The word yes rose to her tongue.

Then he reached for his coffee, and his sleeve slipped back, revealing his watch. Polished metal, intricate face, the kind of thing you saw in glass cases at luxury stores near Westlake Center.

It hit her like a slap. Worlds. His. Hers.

“No,” she said, the word sharp. “I can’t.”

The hope in his eyes dimmed.

“Brianna—”

“You’re a good guy,” she said, cutting him off. “I believe that. But we’re from different universes. You live in penthouses and talk about mergers. I live in a studio in South Seattle and worry about my grocery bill. This… whatever this is… it doesn’t work in real life.”

“It could,” he said quietly. “If we let it.”

“That’s easy for you to say,” she snapped. “You don’t have anything to lose.”

His jaw clenched. “You think I have nothing to lose?” His voice rose, just a little. “You think it doesn’t hurt every time you look at me like I’m the bad guy? Like I’m one step away from ruining your life? You think I don’t go home wondering what else I can do to prove I’m not those men you hate?”

“You can’t prove that,” she said. “Nobody can.”

He stood there for a moment, emotions warring across his face. Then he nodded once, turned, and walked out without his coffee.

Brianna watched him go. Her chest ached like she’d ripped something out of it herself.

So why did doing the “smart” thing hurt so much?

Two nights later, ten minutes before closing, he came back.

“We’re about to close,” she said as he stepped in. The rain had followed him; droplets still clung to his hair.

“I know,” he said. “I just need five minutes.”

He sat at the counter. Up close, she could see dark circles under his eyes.

“I can’t sleep,” he said. “Haven’t really slept in days. I keep replaying our conversations, trying to pinpoint the exact moment I ruined everything.”

“Si-wan—”

“Let me finish,” he said softly.

He took a breath.

“You’re right,” he said. “We are from different worlds. I grew up in a house bigger than your whole apartment building. I never worried about rent or tuition or hospital bills. But—”

He stared down at his hands, flexing them once.

“When I was twelve, my father threw me a birthday party at a hotel downtown,” he said. “Ballroom, ice sculptures, magician, the whole thing. He invited a hundred people. Business partners. Their kids. The mayor stopped by. It was supposed to be… perfect.”

Brianna leaned against the back counter, rag hanging forgotten from her hand.

“He didn’t come,” Si-wan said. “He stayed in New York to close a deal. My mother came for thirty minutes, took photos, smiled, and left for another charity event. I spent the night surrounded by kids who only came for the goodie bags, and I have never felt lonelier in my entire life.”

His voice cracked on the last words.

“I am twenty-eight years old,” he said, “and I run a company with thousands of employees. I sign contracts that affect people across the United States. And I still feel like that twelve-year-old sometimes. Standing in a room full of people who see everything about me except me.”

Brianna’s eyes burned.

“Then I walked into this coffee shop,” he continued, “and you looked at me like I was annoying. Not impressive. Not special. Just some man in your way.”

He smiled faintly.

“That was the most real interaction I’d had in years,” he said.

He met her eyes, letting her see all of it. The fear. The hope. The raw exhaustion.

“I’m not trying to buy you,” he said. “I’m not trying to save you. I don’t want you to be a project I can fix and feel good about. I just… want someone to see me the way I see you.”

Her heart thudded against her ribs.

“I’m scared,” she whispered before she could stop herself. “I am terrified that if I let you in, you’ll realize I’m not worth all of this. That I’m just a barista with a secondhand laptop and big dreams and no safety net. That you’ll wake up one day and think, ‘What was I doing with that girl?’”

He opened his mouth, but she kept going, the words finally spilling out.

“And I’m terrified,” she said, “that if I don’t let you in, I’ll spend the rest of my life wondering ‘what if.’”

The espresso machine clicked as it cooled. Outside, a bus whooshed by on Pine Street. The world went on.

“I can’t promise I won’t hurt you,” he said eventually. “I’m human. I mess up. Clearly. But I can promise you this: I will never lie to you. I won’t make promises I don’t intend to keep. And I will never make you feel like you’re not enough exactly as you are.”

She wiped at her eyes with the back of her hand. “I need time,” she said. “I need to think.”

“Take all the time you need,” he said. “I’ll be here.”

He stood, hesitated, and walked to the door.

“Si-wan,” she called softly.

He turned.

“Thank you,” she said. “For telling me that. About your birthday. About everything.”

He smiled, tired and genuine. “Thank you for listening.”

Three weeks later, everything changed.

Brianna was on her break, scrolling on her phone at the back table by the window, when Jasmine burst in from the register, tablet in hand, eyes wide.

“You need to see this,” she said.

It was an online article from a national business site, the kind that covered Wall Street and Silicon Valley and, apparently, Seattle’s elite.

SEATTLE TECH HEIR REFUSES ARRANGED MARRIAGE, ROCKS BUSINESS ALLIANCE

Below it: a photo of Kang Si-wan in a suit, standing at a podium in a downtown hotel ballroom. The Space Needle rose faintly through the glass behind him.

Brianna’s stomach sank as she read.

According to the article, Kang Industries had been in talks to merge with Park Holdings, another powerful corporation with operations up and down the West Coast. Part of the alliance, arranged quietly like something out of an old movie, involved an expectation: that their children, Kang Si-wan and Park Yuna, would “get to know each other.”

At a formal dinner at a hotel overlooking Elliott Bay, in front of both families, board members, and executives, Si-wan had declined. Politely. Publicly. Loud enough that half the room and all the reporters heard.

“I appreciate the consideration,” he’d been quoted as saying. “But I can’t pursue this arrangement. I’m in love with someone else.”

There was no name. Just speculation about the “mystery woman.”

Brianna’s hands shook.

“Oh no,” she whispered.

“Oh yes,” Jasmine said. “Girl, he just blew up a deal for you.”

“I didn’t ask him to do that,” Brianna said weakly.

“Maybe not,” Jasmine said. “But he did it anyway.”

Within hours, reporters were outside Brew Haven. Not tabloids—that would have been almost funny—but local news and gossip blogs, cameras pointed at the windows. People wandered in pretending to order coffee just to look around. Her face, stolen from old Instagram photos, popped up on clickbait headlines:

WHO IS THE BARISTA WHO STOLE SEATTLE’S MOST ELIGIBLE CEO’S HEART?

MYSTERY WOMAN FROM CAPITOL HILL COFFEE SHOP SHAKES UP BUSINESS ALLIANCE

By evening, her inbox was a mess of interview requests and brand offers she didn’t understand. A cable morning show in New York wanted her to appear via Zoom. A reality show casting director from Los Angeles asked if she’d ever considered “unscripted television.”

Her phone buzzed constantly with unknown numbers. She let them go to voicemail and deleted them.

The next day, she called in sick. Then she did it again.

On the third day, tired of feeling hunted in her own city, she made a decision.

She took the light rail downtown, walked past the glass buildings and food trucks and suits, and stepped into the lobby of Kang Industries.

It was all marble and glass and quiet money. A giant art installation hung from the high ceiling. The receptionist at the front desk wore red lipstick and an expression that said she’d seen every kind of person walk in—but maybe not girls like Brianna.

“I need to see Kang Si-wan,” Brianna said.

“Do you have an appointment?” the receptionist asked, eyebrows lifting.

“No,” Brianna said. “But he’ll want to see me. Please tell him Brianna is here.”

Five tense minutes later, she was in an elevator, badge clipped to her shirt, rocketing toward the top floor. Her reflection in the polished steel walls looked small, curls frizzing, thrift-store jeans and sneakers wildly out of place.

A young assistant led her to a glass-walled conference room with a view of the entire city. Inside, a dozen people in suits sat around a long table. Charts lit up a large screen. It looked like the kind of meeting where people said things like “Q3” and “shareholder expectations.”

At the head of the table, in a navy suit, was Si-wan.

His eyes widened when he saw her.

“Brianna,” he said.

“Can we talk?” she said. Her voice shook, but she held it steady enough.

He looked at his team. “We’ll take a pause,” he said. “Ten minutes.”

“But sir, the merger—” someone began.

“Ten minutes,” he repeated, and his tone brooked no argument.

The room emptied quickly. Briefcases snapped shut. People pretended not to stare as they filed past Brianna.

As soon as the door closed, she turned on him.

“What were you thinking?” she demanded.

He flinched.

“Do you have any idea what you’ve done?” she went on. “There are cameras outside my apartment. Outside Brew Haven. My face is on websites I’ve never heard of. Strangers are calling me, asking if I’m the ‘mystery woman who destroyed a business deal.’”

“I’m sorry,” he said. “I never meant for—”

“This is exactly what I was afraid of,” she said. “Your world turns everything into a spectacle. It’s never just dinner, it’s a statement. It’s never just a relationship, it’s a headline. I didn’t sign up to be a character in some corporate soap opera.”

His shoulders sagged. “I didn’t tell them your name.”

“They found it,” she said. “Because that’s what people do. They dig. They speculate. They comment. And they don’t care that I never asked for any of it.”

“I was honest,” he said quietly. “For once in my life, in that room, I said what I wanted.”

“You were honest at my expense,” she shot back. “You get to say ‘I’m in love with someone else’ and go back to your office while I deal with reporters at my door.”

She took a breath. The words coming next tasted like blood and sky and loss.

“I can’t do this,” she said. “I can’t be the mystery woman. I can’t be your rebellion against your father or your proof that you’re different. I can’t be a scandal, Si-wan.” Her voice cracked. “I just wanted a simple life. Coffee. Paint. Maybe enough money to buy decent health insurance.”

He opened his mouth, but she lifted her hand.

“Please,” she said. “Just… don’t. Stay away from me.”

The sentence hung in the air between them like a guillotine.

She walked out before she could change her mind, head high as she moved through the maze of glass and steel and people who definitely recognized her now.

In the elevator, her legs shook. In the lobby, her throat burned. On the sidewalk, she finally let tears spill, mixing with the Seattle drizzle as downtown traffic roared around her.

Upstairs, in the conference room with the panoramic view of Elliott Bay, Kang Si-wan watched her disappear into the crowd.

He hadn’t cried since he was twelve years old.

That night, alone in his penthouse, he did.

For two weeks, he honored her request.

He didn’t go to Brew Haven. He didn’t call. He didn’t text. Whenever an article mentioned her, he closed the tab before he could read it.

He threw himself into work with a kind of desperation that worried even his most ambitious employees. Twelve-hour days. Back-to-back meetings. He sat in his father’s office and listened to lectures about duty and appearances and, over and over again, loss.

“You embarrassed this family,” Mr. Kang said. His office looked over the same skyline, but from an older, more established building. “You embarrassed this company. You humiliated the Parks.”

“I was honest,” Si-wan replied.

“You were selfish,” his father snapped. “You put your personal feelings above a partnership that would have benefited everyone. Do you understand how the Park alliance would have expanded our reach across the U.S. and Asia?”

“The deal could have gone through without a marriage arrangement,” Si-wan said. “We both know that. Yuna knows that. This was never about business. It was about control.”

His father’s jaw tightened. “That girl from the coffee shop,” he began, disdain dripping from each word. “Is she worth all this?”

Si-wan thought about Brianna’s laugh. About the way she refused his money but took his time. About how she had seen straight through every mask he wore.

“Yes,” he said simply. “She is.”

“Then you’re a fool,” his father said.

“Maybe,” Si-wan said. “But at least I’m a fool who knows what actually matters.”

Days passed. The headlines slowed. The cameras outside Brew Haven disappeared, replaced by tourists and locals again.

In his penthouse, one rainy night, Tae-min dropped by unannounced with takeout from a cheap noodle restaurant Brianna loved.

“You look terrible,” he said bluntly, kicking off his shoes. “When’s the last time you ate something that didn’t come from the executive dining room?”

“I’m fine,” Si-wan muttered, though his blazer hung looser than it had months ago.

“You hurt her,” Tae-min said, digging into his noodles. “You also blew up a near merger, made half the city gossip, and made your father age ten years. So now what?”

“What can I do?” Si-wan asked. “She asked me to leave her alone. So I am.”

“Wrong,” Tae-min said. “You’re doing what you’ve always done: treating everything like a business deal. You made a move, it backfired, so you retreat. Cut your losses. Move on. But this isn’t a quarterly report. You don’t get to just file it away.”

“What am I supposed to do?” Si-wan snapped. “Show up at her apartment and beg?”

“You already talked to the whole city about her by accident,” Tae-min said. “Maybe it’s time you talk to her on purpose.”

“She doesn’t want the circus,” Si-wan said. “She doesn’t want cameras or gossip or any of it. That’s why she walked away. I gave her exactly what she was afraid of.”

“Maybe she still wants you,” Tae-min said softly. “Not CEO you. Not headline you. The you who waited in the rain. The idiot who cried in front of strangers.”

Silence stretched. Outside, another ferry slid across the dark Puget Sound.

“What if I show up,” Si-wan said, “and she rejects me again?”

“Then at least you’ll know you tried,” Tae-min answered. “But giving up because you’re scared? That’s not the man who stood up to his father in front of two hundred people. Find that guy again.”

Two weeks later, Kang Industries hosted its annual charity gala at a hotel downtown, overlooking Elliott Bay, with a view of the Seattle skyline that screamed prestige.

Five hundred people. Business leaders from across the state. Politicians. Donors. The kind of crowd where every name tag meant something.

Mr. Kang insisted his son attend. “People need to see you,” he said. “See that you are still committed to this company. That you can behave appropriately.”

He also, for reasons no one dared question, invited Park Yuna as Si-wan’s “guest.” She arrived in a shimmering gown, composed and kind and heartbreakingly appropriate, her hand resting lightly on his arm as cameras flashed.

What no one mentioned to him was that the event planners, trying to seem community-focused and modern, had invited local artists to display their work in a side gallery. They wanted to connect Seattle’s corporate money with its creative soul.

Which was how, an hour into the evening, with champagne flutes clinking and waiters weaving through sequined gowns, Brianna Matthews found herself hanging her paintings on white walls in a corner of a hotel she’d only ever walked past.

She wore her best dress—black, fitted, bought on clearance at a downtown outlet—a pair of heels she rarely subjected herself to, and her curls piled high to feel a little taller. Her hands shook as she adjusted each canvas.

She’d almost said no when the invitation came. The idea of sharing space with the kind of people who read her name in gossip headlines made her stomach turn. But the chance to show her art, to maybe sell a piece to someone who actually loved it… she couldn’t throw that away.

“I can do this,” she told herself as she stepped back. The paintings glowed under the gallery lights. Abstract swirls of color, portraits of people waiting at bus stops, a skyline dripping into the water.

Then she saw him.

Across the room, near the main ballroom doors, surrounded by people in tuxedos and floor-length gowns, stood Kang Si-wan. He wore a perfectly cut black suit. Yuna stood beside him, shimmering and poised. They looked like they’d stepped out of a magazine. They fit.

Something cracked in Brianna’s chest.

He laughed at something someone said, but his eyes didn’t light up the way she’d seen them at the diner or the coffee shop. He looked… polished. Hollow.

She told herself that was good. Proof that he belonged here, in this world of ballrooms and board members, not in her life.

She started packing her paintings early, sliding them carefully into bubble wrap. If she left now, she could maybe catch the bus before the late-night weirdness on the route kicked in.

“Brianna?”

She froze.

He stood a few feet away, Yuna on his arm, three other people hovering nearby with glasses in hand. Every eye turned to her.

“Si-wan,” she said, forcing her face into something like a smile.

“I didn’t know you’d be here,” he said.

“Yeah, well,” she gestured to the walls. “Apparently my art was ‘local’ enough to qualify.”

Awkward silence stretched, as thin and taut as fishing line.

The people around him waited, hungry for context. For a story.

“Everyone,” he said after a moment, “this is Brianna. She works at Brew Haven, the coffee shop near my office.”

The coffee shop. Not the woman I love. Not the person I risked a deal for.

Just the coffee girl.

Something inside her went still. Then cold.

“Right,” she said, voice quiet but steady. “Just the coffee girl.”

She swallowed.

“Congratulations on the event,” she added. “You all look… perfect together.”

She turned back to her paintings, fingers moving mechanically. After a moment, she heard them drift away, their conversation blending back into the ballroom noise.

She wrapped her art, one canvas at a time, and told herself it was fine. This only confirmed what she’d known from the beginning: she was a phase. A rebellion. A learning experience.

He belonged with people like Yuna, who knew which fork to use and how to talk about stock prices. Not with her.

Thirty minutes later, he was on stage.

The ballroom lights dimmed, casting everyone in a flattering glow. Behind him, through the floor-to-ceiling windows, the city glittered. Someone had written a perfect speech for him about corporate responsibility and giving back to the community.

He held the note cards in his hands, the words a blur.

He started reading.

“In times like these,” he began, “it is more important than ever for companies to—”

Then, out of the corner of his eye, he saw movement. At the back of the room, near the side doors to the gallery, Brianna hefted her paintings, heading for the exit.

His chest constricted.

He stumbled over the next sentence. Someone from PR shifted in their seat.

“I’m sorry,” he said.

The microphone picked it up, projecting it across the room.

He cleared his throat. “I’m sorry,” he repeated, louder this time. “I can’t do this.”

Five hundred people stared at him.

“I can’t stand here and talk about responsibility and integrity,” he said, “when I just did one of the most irresponsible, cowardly things I’ve ever done.”

His father stood up slowly from his seat at the front table, face darkening. PR people looked like they might faint. Phones slid up to record.

“Thirty minutes ago,” Si-wan continued, “the woman I’m in love with was in this room. And I called her ‘the girl from the coffee shop.’ Like she was nobody. Like the last months meant nothing.”

A murmur rippled through the crowd.

“I did it to protect myself,” he said. “To prove to all of you—and to myself—that I could be the man you expect. The CEO who smiles, shakes hands, and never lets anything real show.”

He swallowed hard. His vision blurred.

“In doing that,” he said, voice cracking, “I became exactly what she was afraid I was. A man who can make her life chaos, who can pretend she doesn’t matter when people are watching.”

Tears slid down his face. He didn’t wipe them away.

“She taught me,” he said, “that not everything can be bought. That showing up matters. That consistency matters. That being real matters more than being perfect.”

He looked toward the back of the room. Brianna had frozen by the door, her paintings held tight to her chest, eyes wide.

“I brought cameras to her doorstep,” he said. “I made her a story when she never asked to be one. I proved every fear she had about my world right. And when she told me to leave her alone, I did. Because I thought that was what love meant: giving someone what they asked for.”

He shook his head.

“I was wrong,” he said. “Love isn’t just about stepping back. It’s about standing up and showing up. It’s about being vulnerable even when you’re terrified. It’s about choosing someone—even when it costs you everything people say you should value.”

He turned fully toward the back of the room.

“Brianna Matthews,” he said into the microphone, “I love you. I love your art. I love your stubbornness. I love that you see me when nobody else does. I love that you’ve never once treated me like a prize.”

His voice broke completely now.

“I know I don’t deserve another chance,” he said. “I know I’ve proven every one of your worst fears. But I am done pretending I don’t care. I care. More than any merger, more than any headline, more than my father’s approval, more than all of this.”

He gestured to the glittering room.

“So I’m here,” he finished, “making a complete mess of myself in front of everyone important in my world, because you are worth every second of it.”

He set the microphone down, walked off the stage, and kept walking.

Past his father. Past the donors. Past the stunned employees and the curious journalists. Out through the side doors, into the cool night air that smelled like rain and the bay.

He sank down onto the curb in front of the hotel, the same man who’d once watched her car in the rain, this time without any protection from his own emotions.

He put his head in his hands and let the tears come. The cameras, the whispers, the judgment—it all faded into a dull roar. For the first time since he was twelve, he let himself fall apart in public, not for a deal, not for a narrative, but for himself.

He didn’t hear her footsteps until she sat beside him.

“You really know how to make an exit,” Brianna said softly.

He laughed—a broken, watery sound. “I learned from the best,” he said. “You stormed my boardroom, remember?”

“That was different,” she said. “I was angry.”

“So was I,” he said. “At myself. At my father. At this entire… machine.”

A valet hustled by, pretending not to stare.

“You called me ‘the girl from the coffee shop’” she said after a moment.

“I know,” he said. “I was trying to protect myself. To fit back into this world. To prove to everyone that I could move on. And in doing it, I proved you right about everything.”

“You cried in there,” she said. “In front of everyone.”

“Yeah,” he said. “Your makeup’s all messed up.”

“I’m not wearing makeup.”

“I know,” he said. “Your face is just a mess.”

She snorted. “That was the worst ugly cry I’ve ever seen.”

“Jasmine told you that’s what I do?” he asked, startled.

“What?” she blinked. “Nothing.”

He turned to look at her—really look. Gone was the red carpet version of her. Her dress was simple. Her hair had frizzed a little in the hotel humidity. Her eyes were tired and still the most beautiful thing he’d ever seen.

“I’m sorry,” he said, the words finally landing where they needed to. “I’m sorry for tonight. For the media. For every time I treated you like a problem to solve instead of a person to love.”

“You should be,” she said. “I deserved better.”

“You did,” he agreed.

“I don’t know how to make this work,” she admitted quietly. “Your world still terrifies me. The money. The attention. The expectations.” She stared at the hotel entrance. “But when you were up there tonight, falling apart in front of everyone you’re supposed to impress… that’s when I realized something.”

“What?” he asked.

“I’m more afraid,” she said, “of not trying at all.”

Hope flickered in his chest.

“We do this my way,” she added quickly. “No grand gestures that involve press releases. No buying me cars. No making decisions that put me in headlines without asking me first. Just… us. One day at a time. Pancakes instead of caviar.”

“Anything,” he said. “Whatever you want.”

“And if it doesn’t work,” she said, voice wavering, “at least we’ll know we tried. But…”

“But?” he prompted.

She reached for his hand, fingers threading with his. Her paint-calloused fingertips felt like home.

“But I think,” she said, “it might work.”

He let out a breath he didn’t know he’d been holding.

“Want to get out of here?” she asked. “There’s a diner three blocks over on First Avenue. Open twenty-four hours. Best pancakes in Seattle. Dolores at the counter calls everyone ‘honey’ and doesn’t care how much you’re worth.”

“That sounds perfect,” he said, and meant it.

They stood. He picked up her paintings without being asked.

“I never got to see these up close,” he said.

“They’re just feelings and color,” she said. “Nothing special.”

“They’re incredible,” he said. “Like you.”

She rolled her eyes. “That was cheesy.”

“I’m going to be cheesy sometimes,” he warned. “Fair warning.”

They walked away from the bright hotel entrance, past the line of cars and the glittering people. Past the valet stand where the attendants exchanged looks like they’d just watched the ending of a movie.

Just two people in borrowed jackets and uncomfortable shoes, heading toward neon diner lights.

The Red Star Diner was everything the gala wasn’t.

Cracked vinyl booths. Fluorescent lights. A jukebox in the corner that still played old country songs for quarters. A waitress named Dolores with silver hair and leopard-print glasses who called everyone “sweetheart” and topped off coffee before anyone asked.

“This is perfect,” he said, sliding into a booth beside her instead of across from her, as if they were already united against the world.

They ordered pancakes and eggs and coffee that tasted like burnt hope and sugar.

They talked until the neon signs flicked from bright to faded and the sky over Puget Sound began to lighten.

Not about mergers or scandals or scars. Not even about their fight.

They talked about her newest painting, the one that tried to capture the feeling of standing on the edge of something terrifying and hopeful at the same time. They talked about a mentorship program he wanted to start for Seattle kids who loved business but couldn’t afford internships that didn’t pay.

“Why didn’t you tell me about that before?” she asked.

“I thought you’d think I was showing off,” he said.

“Doing good isn’t showing off,” she said. “It’s just… doing good.”

“I’m still learning how to be a regular person,” he admitted. “I’ve spent so long being the son and the CEO that I’m not sure who I am without that.”

“You’re the guy who waited in the rain,” she said. “The guy who cried at a podium. The guy eating 2 a.m. pancakes in a cheap diner even though he could be in any restaurant in Seattle.”

“I like this better,” he said.

“I do too,” she replied.

Outside, the city woke up. Delivery trucks rumbled past. The first commuters headed toward downtown, cups of coffee in hand, unaware that in a neon-lit diner on First Avenue, two people were rewriting their story.

A year later, Brew Haven looked almost the same.

Same big front windows facing Pine Street. Same indie playlists. Same chalkboard menu. Same trio of college students who treated one corner table like their own co-working space.

Some things were different.

There were three small framed prints on one wall now: photos from her first gallery show in Pioneer Square. A flyer near the register advertised a scholarship program for underprivileged art students sponsored by a “local business leader” who insisted on remaining anonymous, though Brianna knew exactly whose signature had gone on the checks.

Behind the counter, Brianna poured honey and lavender syrup into a mug without needing to ask who the drink was for.

At a corner table, in jeans and a hoodie, laptop open, sat Kang Si-wan.

He looked up as she approached, that now-familiar smile softening his features.

“Remember when you used to write ‘Simon’ on my cups?” he said, taking the latte.

“You were annoying,” she said.

“I was persistent,” he corrected.

“Same thing.”

He laughed and reached into his pocket.

“I have something,” he said.

He placed a thin plastic sleeve on the table. Inside, an old Brew Haven napkin, edges slightly yellowed, ink slightly smudged.

She recognized it immediately.

“You kept this?” she asked.

“I’ve kept this for over a year,” he said. The napkin still read:

I’m sorry that happened to you.

But I’m not him.

“As a reminder,” he said, “that sometimes the right people walk into your life when you’re arguing with an espresso machine in a random coffee shop in Seattle. And that sometimes you have to let your whole life fall apart in public before you figure out who you actually are.”

“That’s very philosophical for a Tuesday morning,” she said, but her throat tightened.

“I have a question,” he said.

She nodded.

“What made you finally say yes?” he asked. “That night at the diner. After everything. After the reporters and the fight and… all of it. What changed?”

She’d known he would ask that someday. She’d thought about the answer whenever she looked at his sleeping face on her couch or painted his silhouette into a skyline.

“You cried,” she said simply.

He groaned. “Best ugly cry of my life.”

“Not to manipulate me,” she went on. “Not to get sympathy. Not to prove a point. You cried because you couldn’t hold it in anymore. Because you cared more about telling the truth than looking like you had it together.”

She took a breath.

“You chose vulnerability over pride,” she said. “Real over perfect. For once, you weren’t trying to impress anyone. You weren’t throwing money at a problem. You were just… you. Messy and honest and brave enough to fall apart in a room full of people who were waiting for you to perform.”

His eyes shone.

“Real love showed up,” she continued, “when you stopped trying to buy it. When you stopped making big offers and just started showing up. When you waited in the rain. When you turned down a merger for someone who kept telling you no. When you chose me, not as a concept, but as a person.”

He squeezed her hand.

“You were worth the risk,” he said. “We were worth the risk.”

“Still are,” she said.

Across the shop, Jasmine pretended to gag and loudly announced she was “totally fine, just something in my eye,” as she wiped at her mascara.

Life wasn’t suddenly perfect. They still had arguments—about money, about time, about the articles that sometimes resurfaced their story when another company tried an arranged marriage alliance.

But they had learned how to fight and stay. How to be from different worlds and build one together.

Brianna enrolled in art school properly, tuition covered partially by scholarships she’d earned, partially by a grant program from a Kang Industries foundation that chose recipients anonymously. She refused to let him write the check directly, and he respected that.

He spent less time at charity galas and more time in Red Star Diner, talking to kids about starting businesses and funding a program for teens on the south side who wanted to learn about entrepreneurship without needing connections.

Mr. Kang never became warm, but he became something better: gradually respectful. He watched his son laugh in Brianna’s company and saw a man, not just an heir. One evening, after a fundraiser, he pulled Brianna aside.

“Thank you,” he said abruptly.

“For what?” she asked.

“For seeing him,” he replied. “Before I did.”

Now, on an ordinary Tuesday in Seattle, the coffee grinder hummed, the rain threatened for later, and the woman who once swore she’d never take anything from a man like him leaned in to kiss him over a latte she insisted he pay full price for.

“Dinner tonight?” his text buzzed her phone later.

That noodle place in the International District you love, he added. The one with the broken sign.

She smiled and typed back.

It’s a date. Your treat.

Always. But only because the noodles are eight dollars, and you’d yell at me if I picked somewhere with a valet.

You’re learning.

I have a good teacher.

She slid her phone into her apron, adjusted her messy bun, and went back to making coffee on a little corner of Capitol Hill that the internet had briefly turned into the center of a scandal.

Just a girl with paint on her fingers, humming along to a bad playlist, in love with a man who had finally learned that some hearts aren’t for sale.

They’re earned.

Day by day. Choice by choice. One honest moment at a time.

News

A WEEK AFTER I FULLY PAID OFF MY CONDO, MY SISTER SHOWED UP AND ANNOUNCED THAT OUR PARENTS HAD AGREED TO LET HER FAMILY MOVE IN. SHE EXPECTED ME TO LEAVE AND FIND ANOTHER PLACE.

My mortgage payoff letter arrived on a Thursday morning in a plain white envelope, the kind that looks like junk…

I GOT HOME LATE FROM WORK, MY HUSBAND SLAPPED ME AND SCREAMED: ‘DO YOU KNOW WHAT TIME IT IS, YOU USELESS BITCH? GET IN THE KITCHEN AND COOK!’, BUT WHAT I SERVED THEM NEXT… LEFT THEM IN SHOCK AND PANIC!

The grandfather clock in the living room struck 11:10 p.m.—a deep, antique chime that made the air vibrate for a…

AS I LAY ILL AND UNABLE TO MOVE, MY SISTER LEFT THE DOOR OPEN FOR A STRANGER TO WALK IN. I HEARD FOOTSTEPS AND HER WHISPER, “JUST MAKE IT LOOK NATURAL.” BUT WHO ENTERED NEXT-AND WHAT THEY DID- CHANGED EVERYTHING

I couldn’t move. Not my arms. Not my legs. Not even my fingers. I lay in the small guest bedroom…

YOUR DIPLOMA ISN’T ESSENTIAL, SWEETHEART. MY SON’S TAKING OVER” HE SNEERED. THE NEXT MORNING, THE CHAIRMAN OF THE BOARD WALKED IN. “WHERE IS SHE?” HE ASKED. MY BOSS BEAMED, “I REPLACED HER WITH MY SON” THE CHAIRMAN JUST STARED AT HIM, HIS FACE BLANK, BEFORE WHISPERING, “MY GOD… WHAT HAVE YOU DONE?!

The fluorescent lights in Conference Room B buzzed like insects trapped behind glass, that thin, electric hum you only notice…

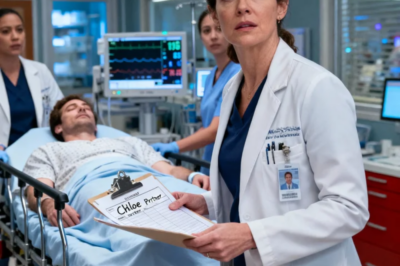

IT WAS SUPPOSED TO BE ROUTINE HE WAS WHEELED INTO MY E.R I CHECKED HIS ‘EMERGENCY CONTACT’ IT WAS ‘CHLOE’ (HIS MISTRESS) LISTED AS ‘PARTNER’ ON THE FORM IT WASN’T ME (HIS WIFE) HE FORGOT I HAVE ACCESS TO EXTRACT EVERY PENNY HE HAS HE WOKE UP TO A NIGHTMARE RED ALERT

The trauma bay lights were too bright, the kind that bleach color out of skin and turn every human mistake…

MY SON SUED FOR MY COMPANY IN COURT. HIS LAWYER-A LONGTIME FRIEND -MOCKED MY CASE AND CALLED ME SENILE. I GAVE A COLD SMILE. WHEN I SAID THOSE THREE SIMPLE WORDS, THEIR CONFIDENT GRINS TURNED INTO SHEER HORROR

The hallway outside Department 3 at the Superior Court in San Bernardino County smelled like floor polish and stale coffee—clean…

End of content

No more pages to load